Abstract expressionists have been immortalized as hard-partying renegades with an aesthetic to match their lifestyle: slashes of color and whirls of movement. Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and others voiced contempt for their artistic forebears, rebelling against social realism (their major stylistic predecessor). Painting was no longer about morals or social messaging: It was performative and emotional.

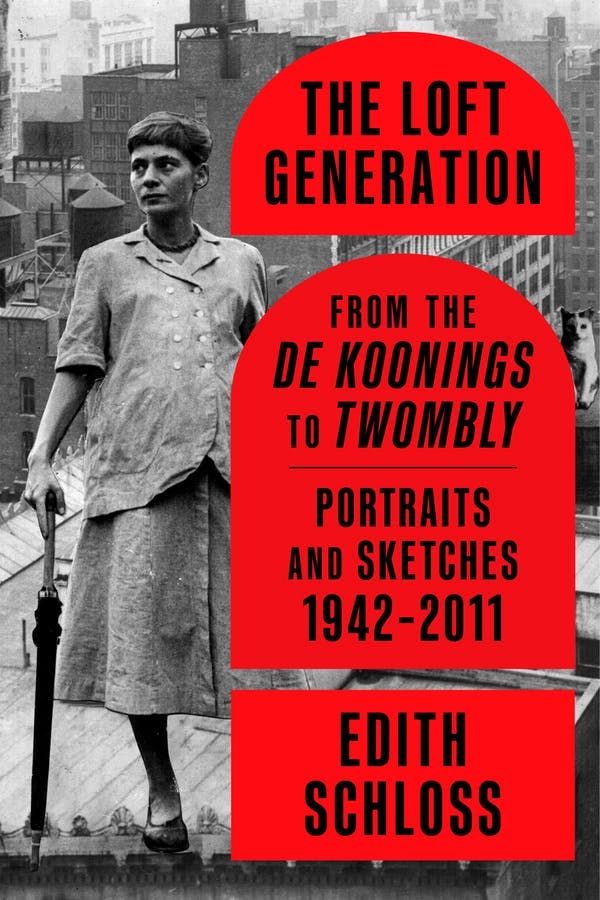

In the postwar years, abstract expressionists began to detest the dogma of creating a better society: They felt things—often angry, turbulent feelings—and smashed them out on canvases in a process called “action painting.” The period, still admired for its transformative rupture from the past, was one of bravado and machismo: Bohemian (primarily) men living in drafty lofts were the heroes in most accounts. This is, in part, the scene that Edith Schloss recalls in her memoir of the era, The Loft Generation: A world of spacious postindustrial studios filled with even bigger ideas about how to reform modern art. But writing with an insider’s perspective, Schloss also hints at currents of sexism and misogyny in the avant-garde, just beneath the surface of those splattered canvases.

An artist and journalist, Schloss moved to New York in the 1940s, a refugee from Nazi Germany by way of the U.K., before resettling in Rome in the 1960s (until her death in 2011). She was particularly good friends with de Kooning but knew everyone in the scene, dropping by their lofts or having them over to her own on West 21st Street in Manhattan. Her memoir, finalized by her son after her death, shows that behind the excitement of artistic revolution was the intellectual and material support of women: wives, girlfriends, and confidants. The Loft Generation celebrates the cultural world abstract expressionists created—eschewing middle-class norms, accepting homosexuality, and largely rejecting the consumer culture of the 1950s—while showing that, as a group, there was widespread erasure of women’s labor and accomplishments, including those of Schloss herself.

The rejection of figurative art was exhilarating as both an aesthetic movement and as a social scene: Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner (one of the few successful female members), Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, and Larry Rivers lived and worked in spacious but derelict lofts in Manhattan using wire spools as coffee tables and burning wooden fruit crates from nearby markets for kindling. They partied with the composer John Cage, the poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, and the dancer Merce Cunningham in the deindustrializing New York of the 1950s. It was a life in sharp contrast to an increasingly suburban America. While Edith Schloss’s contemporaries bought washing machines and electric mixers on installment, her loft friends made things from scavenged rubbish thrown out by nearby factories. As the nuclear family became the basic unit of American life, Schloss’s circle was aggressively nonmonogamous, with many bisexual members—including her husband, Rudy Burckhardt, who kept up an affair with Edwin Denby, a dance critic and translator, during the entire 18 years of their relationship.

Schloss was an artist and writer who had already lived a great deal before arriving in New York in 1942, at 23, to study art. Born into a bourgeois German Jewish family near Frankfurt, she spent her teenage years shuttling across Europe: studying in France, working as an au pair in Italy, and living in the Netherlands, all while the Nazis were coming to power. She eventually helped her parents escape to England, but her grandmother and other relatives were killed, and her father died in a British “enemy nationals” internment camp (most likely of preventable causes). It is remarkable that when she arrived in the United States with her mother during World War II, she did not, as so many Jewish refugees did, seek out a life of American conformity and comfort. Instead, she gravitated toward the avant-garde, making her way around the burgeoning art scene of late-1940s Manhattan. At first, wary male artists viewed her as a somewhat intrusive whippersnapper, while she found them supercilious (but legitimately pathbreaking). She was grudgingly admitted into the scene’s inner sanctum.

Schloss was a visual artist herself and also a writer for ARTnews (her later career was as a journalist in Italy). As a painter, she was overlooked—but as a critic, she had more respect and even a smidgen of authority over gallerists and other painters who ignored her artistic output. The memoir gives written expression to a school of art that is sometimes lampooned. Unlike American novelist Tom Wolfe’s claim in The Painted Word that abstract expressionism only makes sense with copious accompanying explanations, Schloss attests to its ability to move viewers even when the subject matter is unclear. When first visiting de Kooning’s studio as a young art student, she expresses the shock of the new painting style: “Everywhere were surfaces lashed with paint-flows and drips and splatters of paint, linear demarcations and gashes, like frontiers and ghostlike empty spaces, where a canvas had been attacked.” Similarly, when recalling Philip Guston’s work, she tells us: “His dense, gnarly webs of pink, stone white, woolly gray, pomegranate, and indigo strokes made vibrating surfaces that were introspective, hovered rather than moved.”

Schloss’s prose not only expresses what many people have thought and struggled to articulate about the movement. It also gets at the process: “Action painting was also improvisation—the painters holding up their innards, the flesh and heartbeat of color.… They did not call it ‘the controlled accident’ for nothing.” Rarely does a writer describe artists’ lives with the exciting voyeurism of celebrities tied together in a web of sex and booze, while also insightfully commenting on their process, output, and legacy—Schloss manages to do both.

Yet bohemia was not for everyone, and it was often women who suffered the most as they struggled to pay bills, keep their lofts warm, and raise children. Schloss makes clear that her male painter friends had little care for social reproduction, although many had children. As she writes of Elaine de Kooning in a letter “to her” after her death about their friendship: “You never let your estrangement with Bill cut into your stride. When he had a baby with another woman you brought her flowers.” She celebrates Elaine de Kooning’s panache and independence but not her art (like Schloss, her work is mostly overlooked). Even in her posthumous letter, Schloss puts Elaine de Kooning’s marriage to Willem de Kooning front and center: “You chose to be a painter, you chose to marry the best painter of all.… You chose not to cook and slave as a wife, but to dedicate yourself to art and the art world.” She praises her work but mostly commends her for having the foresight to choose the best man of the lot.

Family life was difficult for women in the New York school of expressionists. They were feminists and had their own art practices, but they also did all the care work: “In our world, where painting was so important and living off it was so precarious, raising a family was still rare,” Schloss tells us. “Babies among all that turpentine and paint rags, the toilet on the stairs, the drunk sleeping it off in the hall.” Indeed, on a trip to the Neapolitan island of Ischia, Schloss is left virtually alone with her child in a rural home with few provisions aside from cheese a local boy sells from his backpack. Meanwhile, her husband travels through Italy with his lover, Edwin Denby. It is clear that, while she was friends with Denby and did not resent her husband’s infidelity, she begrudged being left with little money and a child while her husband carried on with a man who, she writes, “made me feel that under his aegis I wasn’t supposed to take painting or writing seriously. He seemed to smile at all this, as if they were harmless hobbies.”

The Loft Generation is speckled with celebrity appearances: Joan Miró examines an apartment as a temporary New York base to prepare for an exhibit, Jane Bowles and her lover hold forth at a party, Allen Ginsberg chain-smokes joints on summer vacation. The style—vignettes that feature noted painters of the 1950s dropping in on Schloss’s life—would be a bit too worshipful if it were not so well written and funny. Only partway through the book one realizes that Schloss, who put together most of the memoir late in life from the remove of Rome, is both feting the abstract expressionists and interrogating the culture they built around themselves. Their group was one of the first to become art stars during their lifetimes, and their paintings had the steepest gain in value ever. Part of that was a matter of changing tastes; but there was also a deliberate endeavor of people like de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg to market their iconoclasm. As de Kooning told Schloss when switching to a more lucrative gallery: “I’m tired of being with a gallery man who believes in art. I’d rather be with a gallery man who believes in dough.”

Life in the lofts was both intellectually stimulating and self-consciously bohemian. Nobody was more scorned than the artists who departed to take newly lucrative jobs in commercial art or advertising and who, afterward, could no longer show their faces at the old haunts in Greenwich Village and Chelsea. While some members of the scene only rented studios near Schloss’s loft (adjacent to the Flatiron Building), most lived there full-time in less-than-comfortable circumstances. Schloss, who raised her son there with little paternal assistance and few amenities, recalls flinging a kerosene stove that burst into flames into the street, after which she casually goes outside and warms her hands over the fire and is soon joined by her neighbor: the painter Robert De Niro Sr.

On a visit to Mark Rothko’s studio in a subterranean former police academy gym, the painter asks Schloss: “Tell me, what’s the weather like up there outside?” She wonders how good art can be made in such a rathole but concludes that Rothko, cut off from reality, could be a “better prophet … as isolated as Moses on the top of the mountain.” However, the poverty conditions were often a performance of artistic squalor rather than actual immiseration and they certainly did not lead to identification with the working class. Schloss makes clear that ideology was distinctly out of fashion with the abstract expressionists, even though many came from Marxist backgrounds and were formerly fellow travelers. This may have been due to stylistic preferences, exhaustion with political art, or an increasingly skeptical view of Soviet power, but Schloss calls social realist art “falsely didactic, or pastoral, without a clear style.” Her friend, the Armenian American painter Arshile Gorky, summed it up as “poor art for poor people.” In Schloss’s crew of friends, bohemia was mostly a countercultural aesthetic, one that celebrated industry and prefigured pop art’s love of mass production, not a statement about art for the people.

By focusing on process and showing the day-to-day lives of now-renowned artists, The Loft Generation avoids hagiography and embraces humor. So often, abstract expressionism is treated as deadly serious: angry young men attacking their canvases and slaying art shibboleths in the process. Schloss shows another side: long summer working sessions in Maine punctuated by humorous games and hilariously bad cooking. Her husband and a friend bury a beloved cat in the semi-abandoned local Sephardic cemetery (although Kaddish was not said). Asked about Alexander Calder’s mobiles, de Kooning replies in a Dutch accent: “All that stuff moving! … He makes me nerfous.”

Even though Schloss writes much of the book from memory in old age, her style celebrates the audacity of the young without sentimentality. John Cage in concert “teased from the old piano’s innards” sounds that were “tinny or dumb; they skipped, limped, or stood still; thrilled, twanged, or bothered your ear. It was bits of silt, sand, sludge, crumbs curdled out of the air.” The reminiscences are not all sweet, but they are bold and stirring, much like the school of art that Schloss knew so intimately.