In 1935, the photographer Dora Maar met Picasso and plunged into an affair with him that would very nearly destroy her emotionally, as he encouraged her latent masochism and betrayed her repeatedly with other lovers. Ten years later, after the war and the affair were over, she suffered a mental collapse for which she was treated by Jacques Lacan, that dubious psychoanalyst de ces jours, who, according to John Richardson, “rescued her by transforming her from a surrealist rebel into a devout Catholic conservative.” As Maar herself said, “After Picasso, there is only God.”

These are the closing words in the fourth volume of Richardson’s mammoth biography of Picasso, and are the last we will have from him, for he died in 2019 at the age of 95. Maar’s confession is expressive of the level of slavish veneration Picasso enjoyed in the 1930s and 1940s, when he had ascended to giddy heights of fame and fortune. The veneration came not only from the ever-accumulating bevy of women to whom he attached himself, but also from his jostling circle of acolytes and hangers-on and, indeed, from much of the wider world as well. People everywhere, including those who knew nothing of painting, knew the creator of Guernica, widely accepted as the quintessential prewar masterpiece, and of the violently distorted portraits of women, and of weeping women in particular, that critics declared objects of surpassing beauty. It was all rather baffling, but the experts are the experts, and Picasso’s supremacy was, and remains, unassailable.

Picasso of course gloried in the glory. After all, he was one of the great showmen of the century, and, as every showman knows, the show must go on, and on, and on, with frequent applications of the whip to the backs of the panting performers. One of the most significant loves of his life, the painter Françoise Gilot, used to address him as “Monseigneur,” and treated as a king in all his majesty the artist who had once signed a self-portrait “Yo el rey”—and he wasn’t joking. There was a certain pathos in all this: Jean Cocteau, the painter’s old friend and toady, was master of the revels at La Californie, the large villa in Cannes where Picasso lived in the 1950s, but no one was in any doubt as to who was in control. “The artist came across as an ancient Grock, who had had his day,” Richardson wrote of Picasso in his first volume, “instead of a great artist in the throes of an exultant regeneration.” What a circus it must have been, with that little black-eyed demon as ringmaster.

Richardson was well placed to write the life of this larger-than-life creature. He met Picasso in 1948 through the English art collector Douglas Cooper, Richardson’s lover at the time. From Cooper’s chateau near Avignon, they would “drive over to Vallauris, where Picasso lived in an ugly little villa, called La Galloise, hidden away behind a garage.” Already here we have a taste of what was to come. Richardson’s biography would be no studiedly dry academic treatise, but a portrait of the artist by a longtime friend.

The advantage is that Richardson and, by extension, we have intimate access to the painter not only at the easel but at home and at the bullfight and on the run from one lover to another, and on, and on. It was “after seeing at first-hand how closely Picasso’s personal life and art impinged on each other” that Richardson decided, in the early 1960s, how he wanted to approach the writing of the biography: “Since the successive images Picasso devised for his women always permeated his style, I proposed to concentrate on portraits of wives and mistresses. The artist approved of this approach.” The biographer would not lack for material, then. Picasso was a master portraitist, and the majority of his portraits were of women, and the majority of the women were his lovers, present, past, and even, in some cases, future.

The disadvantage of Richardson’s closeness to Picasso is an occasional lapse into an embarrassing chattiness, the kind of thing that infuriates the British art historian T.J. Clark. In his book Picasso and Truth, one of the finest studies of the artist to appear in recent years, he lamented “the abominable character of most writing on the artist”:

Its prurience, its pedantry, the wild swings between (or unknowing coexistence of) fawning adulation and false refusal-to-be-impressed, … the pretend-intimacy (“I remember one evening in Mougins…”); and above all the determination to say nothing, or nothing in particular, about the structure and substance of the work Picasso devoted his life to…

However, Richardson did not aspire, or pretend, to bring to bear on his subject or his subject’s art the kind of focused and forensic critical attention that Clark specializes in. A Life of Picasso, which will never now be finished—it stops at 1943, short of the last 30 years of Picasso’s life—is as much a portrait of an age, in all its color and its tragic, and often trivial, goings-on, as it is a biography of one of the titans of that age.

This volume opens with Picasso up to his neck in woman trouble, as so often. In 1932, he was desperately casting about for a means by which to be rid of his Russian wife, Olga, a former ballerina, who from “being an impeccably ladylike consort and hostess, had become a termagant at home.” An injury and a subsequent operation on her left leg had brought Olga’s career as a dancer to an early end. Picasso was impatient of her complaints. Richardson writes: “As the artist once told me”—in Mougins?—“he believed ‘women’s illnesses are women’s fault.’”

At the risk of annoying T.J. Clark by seeming to concentrate on the regions below the belt, one is obliged to observe that Picasso suffered from, or exulted in, a bad case of satyriasis that continued well into old age. He simply couldn’t keep his hands off the girls. Richardson is slow to display sympathy for any of Picasso’s loves, although he cannot but write tenderly of Marie-Thérèse Walter, who was 17 when she became the 45-year-old Picasso’s lover. On an evening in January 1927, Richardson tells us, “while cruising the grands boulevards in search of l’amour fou,” the artist encountered Marie-Thérèse, and fed her one of the oldest lines in the would-be seducer’s promptbook: “You have an interesting face. I would like to do a portrait of you. I feel we are going to do great things together.” For Picasso she was, as Richardson in a previous volume informs us with unwonted, lip-smacking relish, and slightly shaky grammar, “the femme-enfant of his dreams: an adolescent blonde with piercing, cobalt blue eyes and a precociously voluptuous body—big breasts, sturdy thighs, well-cushioned knees, and buttocks like the Callipygian Venus.”

The painter’s prophecy of their doing “great things together” was to be lavishly borne out, in more ways than one. Marie-Thérèse would be his lover, his model, and muse for almost a decade, during which time she bore him a child, Maya, whom he loved and cared for with perhaps uncharacteristic devotion. Picasso did his best to keep Marie-Thérèse a secret. In the summer of 1928, when he and Olga were on holiday in Brittany, he hid her away in a nearby holiday camp. Richardson writes, without much reflection on what Marie-Thérèse might have made of the arrangement: “What perverse, surreal pleasure Picasso must have derived from having his teenage mistress concealed from his wife in a summer camp for children.” Olga suspected something was going on, but wouldn’t discover the truth until the mid-’30s. Marie-Thérèse’s incarnation—the word is apt, surely—in Picasso’s life meant the end for Olga, although Picasso was never to succeed in divorcing her, having to settle in the end for a judicial separation.

In the years that followed, the image of Marie-Thérèse dominated much of Picasso’s work. She is depicted taking languorous part in scenes of bacchanalian rapture—see, in particular, the superb series of etchings known as the Vollard Suite, done between 1930 and 1937—or in many paintings in the form of a sculpted bust set at one side of the canvas and calmly observing Picasso, who takes the stylized form of a god or the Minotaur. He shows her engaged in curiously distracted, melancholy pleasures, in images that are “more tender and wistful than erotic,” Richardson judges.

Marie-Thérèse loved the water, but suffered a number of mishaps and illnesses contracted in or on the sea. In 1932, she fell seriously ill from a spirochetal disease she caught while swimming, or perhaps just kayaking, on the Marne. Four years previously, while at the summer camp where Picasso had hidden her, she rescued one of the other girls from drowning, and almost perished herself while doing so. Richardson observes that “the distress triggered by Marie-Thérèse’s accidents prompted Picasso’s turn to votive magic: ex-votos—vows to gods, be they Mithraic or Christian—in the face of sickness, accident, or death.” Picasso was always deeply superstitious, and had an abiding interest in Mithraism, a Roman cult prevalent in the first four centuries of the Christian era, which involved, among other dark rituals, the sacrificial slaughter of bulls—Picasso was a lifelong aficionado of the bullfight. These quasi-beliefs fed into his work and nourished it, imbuing many paintings, sculptures, and etchings with a kind of sacramental savagery.

Given these interests, and his willingness, indeed his determination, to reach down into the lowest depths of his own being and consciousness, it is no surprise that he should at least flirt with surrealism. He wrote a surrealist play, and composed much—much too much—surrealist poetry, if that is the word for it; some would brand it gibberish, not without reason. Richardson quotes lavishly from the stuff:

“... the necklace of smiles deposited in the wound’s nest by the tempest which with its wing prolongs her caressing martyrdom aurora borealis evening-dress of electric wires throws her in my glass to plunge in full swing sounding her heart ...”

It was a continuing source of irritation to him that André Breton and his flamboyant henchmen had taken over from him the term “sur-realism” and distorted it. “The surrealists never understood what I intended when I invented this word…—something more real than reality.”

Yet the flirtation yielded heat and light, or, more often, a numinously illumined darkness. Richardson writes that Picasso “put no stock in [the surrealists’] obsession with dreams and automatism,” but quotes Picasso’s friend and biographer Pierre Daix’s subtle observation: “what Picasso drew from Surrealist ideas, was the liberty they gave to painting to express its own impulses, its capacity to transmute reality; its poetic.”

One of the ghostly figures that haunted Picasso all his life was that of his adored sister Conchita, who died in 1895, at the age of seven. Pablo, a prodigy at 13, had made a vow to God that if Conchita’s life was spared he would never paint again. Richardson repeatedly refers to this as the “broken vow,” though it is hard to see how it was broken, since God took no notice of the boy’s promise. All the same, “the beloved child’s early death would cast an inescapable shadow over virtually all of Picasso’s relationships with women, especially that with Marie-Thérèse.” Certainly, as the years went on, the image of his lover became melded with that of his lost sister. One of Picasso’s most famous sculptures, and the one that, significantly, he ordered to be erected over his grave, was Woman With Vase of 1933. Richardson specifically identifies this sculpture with Conchita.

In one of Picasso’s great works, the engraving Blind Minotaur Led by a Girl Through the Night from the Vollard Suite, and what could be argued is his greatest work, the etched and engraved La Minotauromachie, both from 1935, Marie-Thérèse is conflated with Conchita, directly so in the former, by suggestion in the latter, in which a girl-child holds aloft a guiding light.

Once seen, Minotauromachie is never to be forgotten; mysterious, deeply fraught, and yet suffused with calm and resignation, it seems to contain all of Picasso’s themes, including a fanciful self-portrait in the figure at the left climbing a ladder, the girl with the light held aloft, the Minotaur—“Picasso’s mythical alter ego as a figure of immense, albeit flawed, power,” writes Richardson—and a bare-breasted Marie-Thérèse sprawled on her back across a disemboweled horse and gripping in one hand a sword with which it seems she will put the poor animal out of its misery. This work was made as Spain was slipping toward civil war, and is a far more resonant emblem of the darkness of the times than Guernica (1937), which appears vulgar and bombastic in comparison.

Richardson, inevitably, devotes a chapter to Guernica, which commemorates the destruction by Luftwaffe bombers of the Basque town of that name. The atrocity had been planned by Hermann Göring as a gift on Hitler’s birthday, April 20, but for logistical reasons it had to be put off until April 26. Nevertheless, the Führer was delighted by what the commander of the operation described in his diary as “absolutely fabulous … a complete technical success.” The city was flattened, and more than 1,500 civilians died.

Picasso felt he had to do something, to go to war in his own way. The result was Guernica, a gigantic canvas 25 and a half feet long and 11 and a half feet high, executed in a matter of weeks in his Paris studio on the rue de Grands-Augustins. At the time, the artist had his doubts about the work, doubts he later clarified to a friend, saying he preferred to it the Three Dancers of 1925: “It was painted as a picture, without ulterior motive.”

Others agreed. The film director Luis Buñuel, who helped in the hanging of Guernica in the Spanish Pavilion of the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937, couldn’t stand it. “Everything about it makes me uncomfortable—the grandiloquent technique as well as the way it politicizes art … [I] would be delighted to blow up the painting.” What Buñuel and a few others spotted was that for all its overweening gigantism, Guernica is essentially a piece of kitsch. Picasso might have got away with calling it, after Goya, The Disasters of War, but tying it to a specific place and event was to rob it of its autonomy, the autonomy that, whether we like it or not, a work of art must assert in order to be fully and freely authentic.

Picasso was always an artistic chameleon, and never more starkly so than in March 1935. Minotauromachie is dated March 23. Six days later, he produced a truly extraordinary scene in oils, The Family, which Richardson, exercising considerable restraint, describes as

a large, somewhat banal landscape with figures, which bears no relation to anything he had ever done.… In [the picture] his mother clutches baby Conchita. Standing between her and the father are little Pablo and his sister Lola. The desolate landscape evokes … the painful winter of Conchita’s death in 1895, the season of the broken vow.

And it would go nicely on the lid of a chocolate box. What was he thinking of? Richardson doesn’t even hazard a guess, and probably we should follow his lead and pass on in silence. Still, the soupy sentimentality of the picture does jar.

Accounts of the twin affairs with Marie-Thérèse and Dora Maar occupy much of this fourth volume. Picasso took a sadistic delight in tormenting the increasingly masochistic Maar—she is the woman who does most of the weeping in Picasso’s work—not least by imposing on his portraits of her frequent strong echoes of Marie-Thérèse’s unique and immediately identifiable features. It pleased him also to depict his detested wife, poor, lamed Olga, as a snake-tongued monster in a ridiculous hat. In another one of Richardson’s intimate confidings, he tells of sitting with Picasso at a corrida in Nímes sometime in the 1950s. “He turned to me and said, ‘those horses are the women in my life.’” The current woman in his life, his second wife, Jacqueline Roque, winced, as well she might, as the poor horses down in the ring trod on their own bloodied entrails.

He could be fiendishly cruel. One night, he took Olga and their troubled son Paulo to a performance of Pagliacci. “Back home, he undressed Olga most affectionately before making love to her.” Next morning, the maid announced that there was a gentleman waiting in the salon to speak to Mme Picasso. Olga tried to get her husband to go and see who it was, but he insisted she must go herself.

Ten minutes later, Olga returned from the salon, looking very pale, clutching a document the visitor had given her: a summons to appear in court in order to respond to a divorce suit that her husband was bringing against her. Picasso wandered off, singing Pagliacci at the top of his voice.

Picasso had for the most part what the English describe as a “good war.” He had his frights, not the least of them when it seemed that Franco would persuade the German occupiers to extradite him from Paris to Spain, where the Caudillo and his triumphant fascists would have made short work of him, for all his fame. He also showed a talent for bamboozling the authorities, and was able by quick thinking and quicker talking to foil attempts by the Germans to seize a bank vault in which he and Matisse had stored stacks of their work that were worth millions.

At the close of the volume in early 1943, the war had been going for three years, Dora Maar’s mental health was in decline, and her mother had died. Once again, Picasso behaved appallingly. “Dora would later say that when Picasso saw her dead mother on the floor, he ‘made a circus of it, coming and going with his friends … it was revolting. In order to belittle death, you see, because he’s so terrified of it.’”

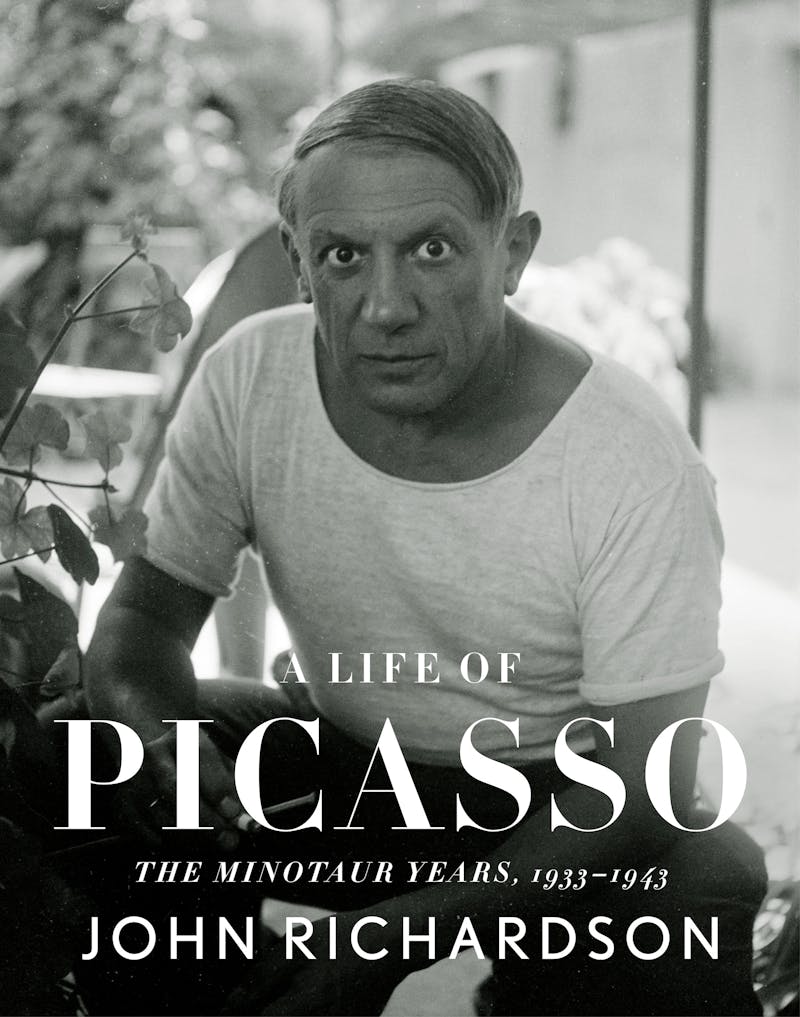

The frontispiece to the book is a striking photograph of Picasso, taken by Lee Miller in—you guessed it—Mougins in the South of France in 1937. The painter is seated side-on to the camera and delivering to the lens his famous mirada fuerte, or strong gaze, “prized by Andalusians as a source of sexual power,” Richardson informs us, and he goes on to say that “the equation of vision, sexuality, and art making is the key that often unlocks the meaning of Picasso’s work.” The largeness, and the vagueness, of this statement are typical of Richardson at his worst—though one must add that in this final book, written in his eighties and nineties, he is more often at his best.

It is not vision, or sexuality, or perhaps not even art, that is the constituent of Picasso’s greatness, but his unrelenting program to deny human beings the comfort, and the escape, of truth—manmade truth, that is. Picasso would counter Keats’s dictum that “beauty is truth, truth beauty” by staring the poet hard in the eye and saying, Yes, and both are lies. As T.J. Clark puts it: “Is not [Picasso’s] the most unmoral picture of existence ever pursued through a life? I think so. Perhaps that is why our culture fights so hard to trivialize—to make biographical—what he shows us.” Yes, biographies stylize, and in the process to some extent trivialize, a life, yet Richardson’s enormous labor of love does throw light upon a dark, often destructive, but always creative modern master.