The publishing industry loves nothing better than writing about itself. The last year or two has seen a clutch of books about great publishing impresarios and their lives, whether biography, fiction, or memoir. Boris Kachka's wonderfully juicy Hothouse revealed the inner workings of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux (and the sexual antics of its editors). Jonathan Galassi, the current publisher of FSG, has written a novel about an editor at an independent publishing house, titled Muse. The power agent Sterling Lord memorialized his successes in the not-bashfully named memoir, Lord of Publishing; Robert Calasso of the Italian house Adelphi Editions offers more measured reflections on the industry in his forthcoming The Art of the Publisher. Of all these, none is as powerful as a new memoir by George Braziller, who in 1955 founded an eponymous small press that did very big things. At 99 years old, his memoir Encounters: A Life in Publishing, is the first book he's written.

It begins with what is, for any editor, a striking admission: “I felt that I wasn’t a good writer, and writing came sporadically and painfully,” he writes. And perhaps more striking still: “I looked at every how-to book on writing.” The resulting memoir is written in a purposely plain style: Sentences feel as though misleading adjectives and clauses have been sheared from them, in an effort to keep memories in focus. It is, in other words, a self-taught style—which is especially fitting for a publisher, whose skill is to see the originality in others, and not to cultivate it in oneself. The book is structured as a series of vignettes (he took the idea from Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days) that trace his life from his family background to the wider family of writers he published. Taken together, they are a testament to his skill at recognizing great writers.

For a small publishing house, George Braziller, Inc. is notable for having published the first novel of Orhan Pamuk, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for literature, as well as books by Einstein and Jean-Paul Sartre. In the early years of his press, he went to Paris, and came back to America with works by Andre Malraux, Claude Simon, and Nathalie Sarraute, pioneers of the nouveau roman. Among the poets on his list is former U.S. Poet Laureate Charles Simic, whose poem “Elementary Cosmogony” is a veiled tribute to his publisher: “the invisible / came out for a walk / on a certain evening / casting the shadow of a man.”

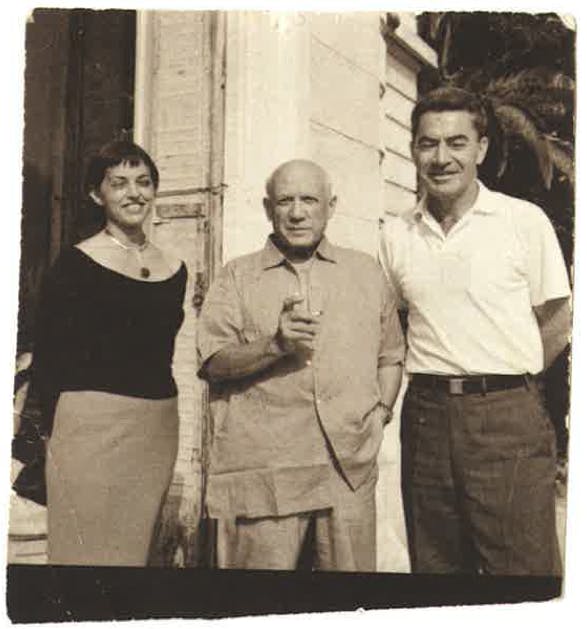

Unlike Galassi and Kachka’s books, Braziller’s encounters with the great writers and artists are not described as glamorous, but rather as awkward and humbling. In one scene, Braziller recalls meeting Marc Chagall at his studio in Paris, hoping to win Chagall’s approval to publish an English edition of Daphnis and Chloe in America. Awed and slightly intimidated, Braziller gets sidetracked into a long conversation with Chagall about poetry. As he’s leaving he realizes he hasn’t managed to seal the deal. Chagall saves him: "Suddenly, he took my arm, looked at me and said, 'You have my permission.'" Of meeting Picasso for supper, Braziller writes simply, “I was flabbergasted.”

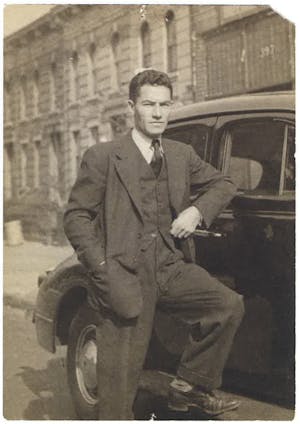

You can see in Braziller’s recollections of growing up in a tenement in Brownsville his affinity with some of the writers he published, particularly Charles Simic. His sense of humor recalls Simic’s prose poem “We were so poor I had to take the place of the cheese in the mousetrap.” Braziller was born in 1916; his parents had fled Russia in 1900, and, after his father’s early death, his mother sold used clothes and shoes from a cart to support their family of eight. To make extra money, the young George realized that he could exploit the fact that their building had only one toilet on each floor: “I knocked on the doors of the best tippers to alert them that they should take occupancy.” During the Great Depression, he made money working as a model for luxury camel coats, which involved being driven around New England in a black Buick by a shifty (and rakish) salesman named Nat Tepper.

The Great Depression also sparked Braziller’s first successful business venture. In the 1930s he found himself working for his brother in law, who owned a remaindered books warehouse. He saw an escape from daily drudgery in a brilliant scheme: Inspired by the Left Book Club in the United Kingdom, he founded a book club that would select and distribute affordable books to a working class audience. By the time he signed up to fight in World War II, the Book Find Club had 20,000 members; when he returned in 1946, membership had grown to over 50,000 under his wife’s leadership, and was commercially successful. By the McCarthy era, around five years later, it had become considered politically suspect for promoting “thoughtful, ‘liberal’, ‘left-wing’ books.” Thousands of club members, Braziller writes, "called into our office or arrived in person, begging that we destroy their membership cards, hysterical with fear that they would be accused of being communists." The Brazillers later sold the club to Time-Life, which inexplicably wound the whole enterprise down within two years.

The Book Find Club led to the Braziller family’s friendship with Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe. Braziller and his wife Marsha had selected Miller’s 1945 novel Focus as one of their monthly selections, and had started to spend vacations together on Long Island, a relationship that continued long after Death of a Salesman made Miller famous. One of the high points of the book is when Braziller recounts an evening the two families shared, “dancing and singing and it got quite late”:

Finally, we all went to bed. While in bed, I turned to Marsha and said, "Gee, I kissed Marilyn." "Big deal," she said. "Arthur kissed me."

Braziller’s memoir revisits moments like this in short, almost sparse entries. It’s impossible to appreciate their richness without also sensing the loneliness out of which they emerge. He started writing this book only when he retired, four years ago, at age 95 and began to see the world the world as newly bare. “A number of friends I had once partied and traveled with,” he realized, “were now deceased.”

At 95 too, he read War and Peace for the first time, reread Whitman, and thought about what it meant to be a writer. Ultimately it was a few lines by the literary critic Clifton Fadiman that helped him recover his past and his faith in literature. Fadiman’s comments “inspired me with such a joyous feeling that I started to write,” Braziller writes. “Perhaps I make starting sound easy.”