What Fossil Fuels Have Done to Summer Is Unforgivable

There’s nothing fun about deadly heat.

Ah, Memorial Day: the time to haul out the grill, peruse those make-ahead salad recipes, and throw your back out dragging your aging air conditioner out of the closet, because it’s going to be a heck of a summer.

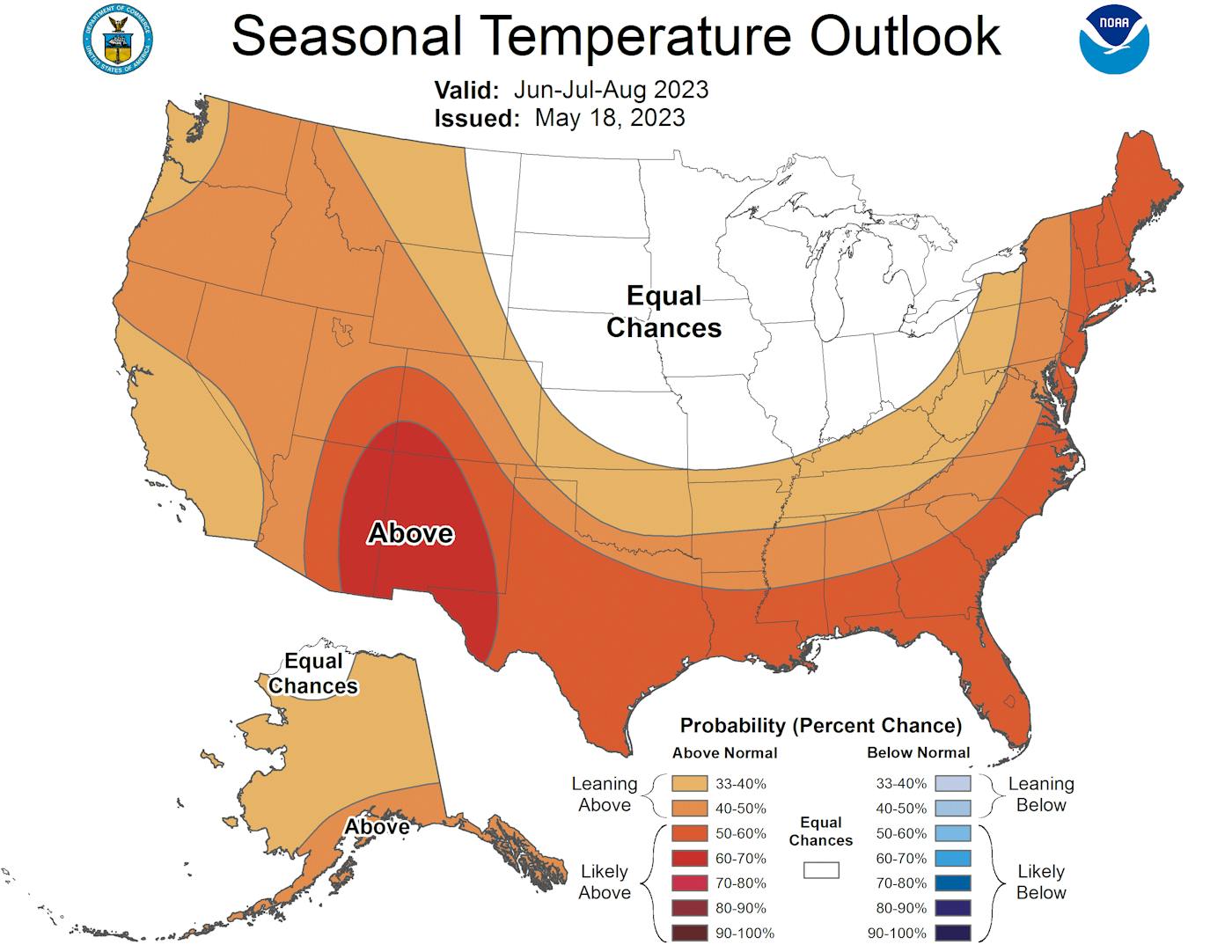

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently unveiled its seasonal temperature outlook, which estimates most of the United States is likely to experience above-normal temperatures this summer. The probability of that outcome depends on where you live, ranging from 33–40 percent in West Virginia and central Montana to 60–70 percent in parts of the Southwest.

NOAA also released its Seasonal Precipitation Outlook, which predicts that much of the Midwest, South, Southeast, and Mid-Atlantic may experience above-average precipitation, while the Southwest—already in crisis due to an ongoing drought—is likely to suffer from below-average precipitation, which could also hit the Pacific Northwest. (The 2023 hurricane season outlook will be announced at a news conference later this week.)

Global warming gives us different things to mourn in different seasons. The changing climate, for example, can make people nostalgic for the autumns and winters of yesteryear—you know, when leaves changed color on schedule and drinking hot cider in October didn’t just make you sweat, or when backyard skating rinks didn’t melt into vernal pools in January.

But climate change’s effect on summer feels simultaneously more subtle and more foreboding. It doesn’t make summer less summery. But it does make summer less fun and more dangerous, in a variety of insidious ways.

At the more prosaic end of the spectrum, 75-degree days turning into 85- or even 90-degree days is just an unpleasant hassle, making it harder to enjoy the outdoors and more costly to keep the indoors comfortable; air conditioners are expensive and a pain to deal with, and heat screws up people’s sleep.

Then there are the deadly waves, whose toll is probably undercounted in this country. “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” Eric Margolis previously wrote for TNR, “only counts deaths where heat illness is explicitly noted, so the official CDC count of heat-triggered deaths sits at just around 600 per year. Epidemiologists estimate that the real figure may be closer to 12,000—20 times higher than the official count.”

Those numbers could soon rise. For a while, heat deaths were decreasing—probably due, the CDC has surmised, to “better forecasting, heat-health early warning systems, and increased access to air conditioning.” But there are a few reasons that trend might not hold. For one, the number of dangerously hot days in many areas is growing. Here in D.C., for example, the “baseline” number of heat emergency days is supposed to be 11. But by the 2050s, even under a “low emission scenario,” that number will more than double, to 25—and could be as high as 45. (Already, this decade, the city is expecting the number of heat emergency days to range from 18 to 20.)

The second reason is that air conditioners, which are hardly evenly distributed across society to begin with, aren’t much help if the electrical grid fails. In the 2021 heat wave that hit the Pacific Northwest, over 6,000 people lost power in Portland alone during a 112-degree-heat weekend. As Vox reported that year, the U.S. power grid is dangerously underprepared for these kinds of scenarios, and not just because of overall energy capacity: “If the weather gets hot enough, power lines start to sag—a result of the metal inside them expanding—and risk striking a tree and starting a fire. At the same time, power plants are highly dependent on water, which they need to cool down their systems,” but which isn’t necessarily available in some areas during drought.

And that’s to say nothing of work-related heat deaths, for both outdoor workers in fields like agriculture, construction, and delivery and indoor workers in poorly ventilated warehouses. It’s to say nothing of the increasingly plausible link between heat and derechos, or the dangers of drought, fire, or flash floods—all of which climate change is making more likely in various regions in the summertime. It’s to say nothing of the well-documented annual spike in violent crime, which researchers show is particularly likely on days above 85 degrees.

As a fall and winter person myself, I spend a lot of time mourning what petro-hegemony is doing to those seasons. But what rampant emissions are stealing from summer people—and all of us—is arguably worse. Climate change isn’t simply removing what’s enjoyable about these months (like snow in winter). Instead, it takes those enjoyments and dials up the temperature until the fruits of the season start to rot—until the former beach days, al fresco park gatherings, and mornings in the garden just aren’t very pleasant, or even carry the risk of heat stroke, and “scorchers” turn into multiday death traps.

Happy unofficial start to summer. It’s a lovely time to get angry and demand better.

![]()

Good News

California, Arizona, and Nevada have come to an agreement on water cuts to address the crisis in the Colorado River basin. It’s not final, and it’s absolutely not enough to resolve the situation permanently. But after an incredible amount of stalling, it’s a start.

![]()

Bad News

The G7 meeting in Hiroshima over the weekend failed to result in a commitment to coal phaseout and included explicit praise for natural gas: not a great outcome for the climate.

Stat of the Week

.png)

That’s what the top fossil fuel companies (think BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, Total, Chevron, and more) would owe in regular reparations for the cost of extreme weather, sea level rise, and other climate disasters, according to new hypothetical calculations.

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem

She’s Out to Save Rare Wildflowers, but First She Has to Find Them

One of the upsides of California’s torrential rain earlier this year has been a “super bloom” of wildflowers. That gives botanists a brief window in which to locate rarer species and possibly save them from extinction, Jill Cowan reports:

This spring and summer, Dr. Fraga and other rare-plant biologists are in an exhilarating race to find wildflowers before they disappear again.

The botanists’ ultimate goal is to secure endangered or rare species designations for the most threatened plants. That can lay the foundation to legally force land managers to make accommodations for threatened species. (For instance, the Center for Biological Diversity has made wildflower protection a key piece of its lengthy fight against development of the Tejon Ranch, where almost 20,000 new homes have been proposed north of Los Angeles.)

In order to get endangered or rare species designations, Dr. Fraga and her colleagues must first prove that the plants still exist.

Read Jill Cowan’s report at The New York Times.

This article first appeared in Apocalypse Soon, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by deputy editor Heather Souvaine Horn. Sign up here.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)