“A great deal of hokey art has been made in the service of excellent causes.” Thus begins Robert Hughes’s pan of the feminist artist Judy Chicago in a December 1980 issue of Time. He was reviewing her massive installation, The Dinner Party. The work is a triangular dinner table set with 39 places; each of the embroidered place settings names a different famous woman from history (Boadicea, Elizabeth I, Margaret Sanger, Ethel Smyth). Each of their places is set with a golden chalice, a napkin, and a china plate 14 inches across decorated with vaguely vulval forms. Susan B. Anthony’s resembles a pink four-petaled flower; the Greek mathematician Hypatia’s is a design of swirling leaves in a similar shape. As if evoking the variation between actual vulvas in real life, some are done in a kind of surging bas-relief, while other plates are flat.

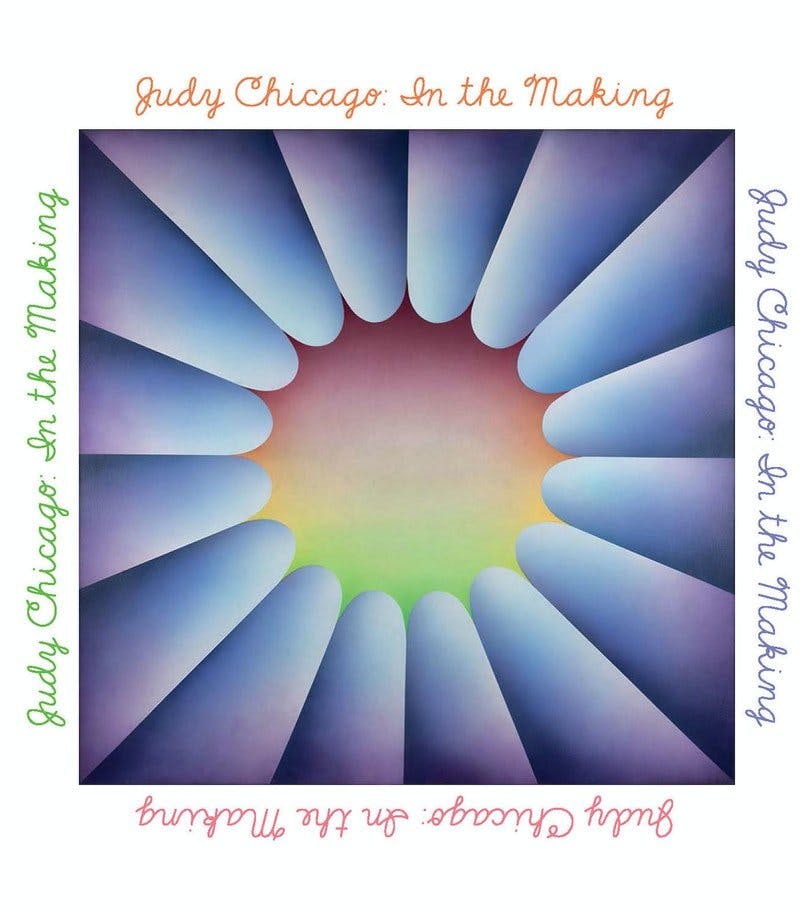

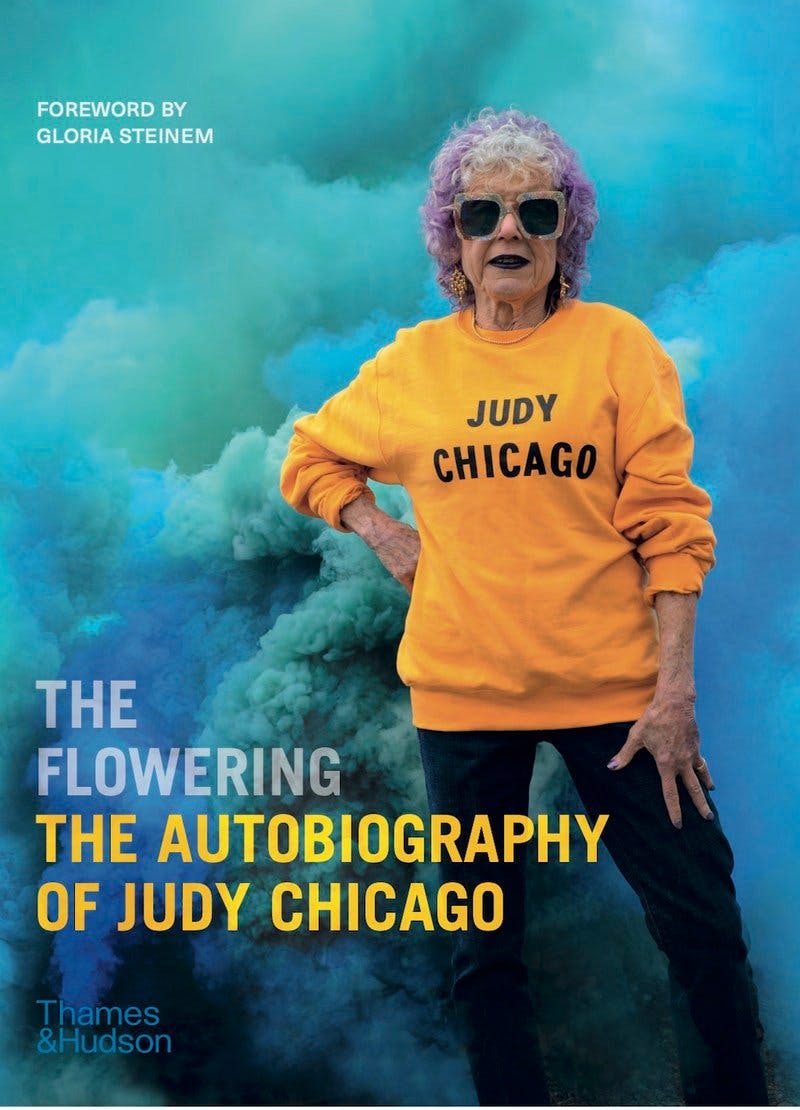

Attacks on The Dinner Party became a major part of Chicago’s story as an artist. In both her new memoir, The Flowering, and the book accompanying her current career retrospective show at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Judy Chicago in the Making, she cites Hughes’s review as evidence of the hostility she encountered from sexist critics. Buffeted by rejection—she also got a bad write-up from Hilton Kramer at the Times—Chicago struggled to find museums that wanted to display the piece, and her collaborator Diane Gelon had to strive to get it shown. Chicago attributes sexist critics with the fact that The Dinner Party did not find a permanent home until 2002, when the Brooklyn Museum rescued it from its storage crates.

Like many women artists of her generation, Chicago has garnered more attention in her later years. (Jillian Steinhauer articulated the irony of belated recognition now coming to so many older women artists in her recent essay, “Old Women,” citing artists like Carmen Herrera, Cecilia Vicuña, and Zilia Sánchez, who have been miraculously discovered in their dotage, just in time for some curator to make their name.) The restoration of Chicago’s reputation was arguably completed in 2018, when Hanya Yanagihara of The New York Times put her on the cover of T magazine and the newspaper published a survey of critics’ reviews of her work over the years, symbolically repudiating the anti-Chicago stance it had taken before.

Yet even as her renown has grown, the storm over The Dinner Party has tended to obscure her other work. My favorite Judy Chicagos are in the Great Ladies series of paintings, done in 1973. Each named for a distinguished or notorious woman of history, including Marie Antoinette and Madame de Staël, they all depict waves radiating out from a central point, usually undulating or otherwise appearing to be in motion, in largely symmetrical formation. They’re captivating and almost viciously aggressive, their gaze unblinking, like the noonday sun staring down at you.

My least favorite Judy Chicago work is a lithograph print titled What is Feminist Art?, done in 1977. Like many of her works it involves a lot of writing; here there are two columns of it, in typewriter font. On the left, there is a somewhat abstracted but recognizable drawing of a vulva. At the top, a rubric: “Feminist art is all the stages of a woman giving birth to herself.” Down the middle, between the paragraphs, are small drawings: a triangle, a thing like a coffee bean, a sketch of the Venus of Willendorf, a shape like somebody birthing, two images from her own paintings, and a stick figure, its limbs extended, that looks like it came from Indigenous Australian art. The writing is quite good, if you actually read it. If you don’t, the work mostly invokes that signature look, the white feminist using vaguely “primal” symbols in order to connect with a concept of the ancient feminine divine, or something.

How could the same person have made both of these pieces?

Judy Chicago was born Judith Sylvia Cohen in, surprise, Chicago, her parents “Jewish liberals, with a passion for the intellectual life and seemingly endless energy for political activism,” she writes in the new memoir. In an interview for the exhibition book, she says,“when I was a child, people kept dropping dead all the time around me.” Her father died when she was 13, and a number of family members passed away around the same time, including an aunt’s husband, shot to death. Horribly, when Chicago was 17, her childhood best friend and her whole family were killed at a railroad crossing. At 23, her first husband, Jerry Gerowitz, died in a car accident, the day after their Labrador died.

This strong awareness of mortality seems to have some kind of connection to the force that animates all her work, and may be the source of Chicago’s powerful will as a personality. While in graduate school at UCLA, she presented her 1964 Bigamy Hood to her teachers. This gorgeous piece, made the summer after Jerry died, is a symmetrical extrapolation of gonad forms and phalluses and broken hearts, painted in automotive lacquer on a car hood; it’s a work about male and female, emotion and shapes, décor and horsepower. When she showed it to her two instructors, they both “became irate,” making “irrational objections” to the work. She didn’t understand their upset, “and obviously, judging by their reactions, neither did they.” Then, as if part of a play intended to teach children about the unimaginative ways of the twentieth century American male, one of them “sputtered something about not being able to show the paintings to his family and then left.”

It’s precisely the kind of reaction you would never get now, and it’s surreal in the face of the piece’s beauty. She was laughed at even when, in 1965, she made Rainbow Pickett, a perfect slant of sunbeam translated into cuboid form. Chicago trained in automotive spray-painting after college and mastered all kinds of finicky techniques, but gradually came to repudiate her part in the “Finish Fetish” obsession with glossiness and cars, as well as the minimal style of sculpture that works like Primary Structures (1966) embodied so well. Moving into performances using colored smoke and fireworks—ephemeral and yet totally form-involved works—Chicago continued throughout the 1960s to find new forms and little recognition. All of these early works exhibit originality and innovative uses of materials, but professors and critics turned their noses up at them, as Chicago recounts at length in her new autobiography—her third, after 1975’s Through the Flower and 1996’s Beyond the Flower.

In 1970, she took out a full-page ad in Artforum, announcing that she would drop the last name Gerowitz. Rolf Nelson, the gallerist who first displayed Rainbow Pickett, had nicknamed her Judy Chicago partly for her “strong Windy City accent,” she writes, “but also because he thought it suited the tough and aggressive stance I had felt obliged to adopt in order to make my way in the macho art scene that was Los Angeles in the 1960s.” It was fashionable at the time. Her peers made a lot of “macho announcements,” she writes. She staged a photograph of herself in a boxing ring, wearing a sweatshirt with her name on it. Two years later, Chicago co-founded a feminist art program at Fresno State College, a women-only pedagogical experiment that resulted in the techniques she used to create Womanhouse (1972). In her first truly ambitious curatorial work, Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, and 21 other women artists drenched an old mansion in performance and visual art, all geared toward the uncompensated and unheralded work women traditionally do in the home. One drawing sat out on the lawn until it melted.

Chicago and her by-now large retinue began work on The Dinner Party in 1974, and continued until it was first shown in 1979. What some critics hated was the genitalia, the reductive and essentialist way she related vulvas to names. In his review, Hughes quotes her first autobiography, in which she explained why she was so interested in the pudenda:

To be a woman is to be an object of contempt, and the vagina, stamp of femaleness, is despised. The woman artist, seeing herself as loathed, takes the very mark of her otherness and by asserting it as the hallmark of her iconography, establishes a vehicle by which to state the beauty and truth of her identity.

Hughes makes that trickiest of critical moves, quoting Chicago at length as if to let her make herself ridiculous all on her own. He calls her writing “this jargon-sodden Femspeak,” an attempt to “set up a myth of women artists as a hated underclass, which they were not in 1975 and are not today,” a claim that does not jibe with the most recent data.

In response to these critics’ rejection, Chicago turned to a different way of working. She spent much of the rest of her career collaborating on dizzyingly complicated needlework projects with hundreds of other women across the country, exploring what she thinks of as eternal feminine forms in series like the Birth Project. It’s very hard to make drawings out of thread, and it’s also hard to share credit among a group of needlework collaborators. Her turn to textiles and needlework, as well as glass—all of which look underwhelming in reproduction on the page or screen, though they’re powerful in real life—feels almost like a wry act of self-sabotage, or a feminist satire on the macho Finish Fetish of the ’60s.

What to make of Judy Chicago’s vulvas now? When Amelia Jones wrote for the catalog to a 1996 Chicago show, she observed that The Dinner Party is to many people “exemplary of 1970s feminism’s supposed naïveté, essentialism, universalism, and failure to establish collaborative alternatives to the unified (and masculinist) authorial structures of modernist art production.” Nancy McCauley put it more bluntly in 1992: “Essentialism is a hallmark of Judy Chicago’s work: she used vaginal imagery and craft media as a blazon of ancient traditions,” she wrote.

McCauley was not condemning Chicago for her essentialism but rather explaining the gulf between the feminist essentialism of the movement Chicago emerged from and the postmodern feminism that emerged in the 1980s and ’90s, which bristles against the positing of biology as more important for the experience of gender than, say, socialization, and suggesting that The Dinner Party has fallen into it.

The Dinner Party was never a success as a vision of feminist possibility. The vast majority of the women it features are white, with miscellaneous ancient goddesses added from a variety of cultures; the selection is so random that it reads more a live-action version of what Judy Chicago happened to know about in the 1970s than anything else. Sojourner Truth’s plate has no vulva on it; only three Black faces. In a paragraph now featured on Sojourner Truth’s “setting” at the Brooklyn Museum’s website, Chicago has written that when she was researching Truth, “there was very limited information about her or other women of color, although it was clear that Black women were an important force in the nineteenth-century abolition and feminist movements. Their activism laid the groundwork for the swelling of activism today, and it is thrilling to me that the historical record is being expanded and corrected.” Frankly, this is a poor defense—in the books, Chicago frequently refers to the impossibility of finding information that plenty of experts had access to, at the time, if she had been willing to ask.

It would be too easy to reassert the “essentialist” label now, without any admission of the taboos, as well as the balls, that Judy Chicago busted. I always thought the pussy plates were supposed to be funny, as in eating. They’re not the most interesting feature of The Dinner Party, anyway; that distinction goes, in my opinion, to the fact that there’s nobody at this elaborate table. The absence of people makes the whole scene quite frightening, like the empty Throne Room at Cair Paravel in the Narnia books, as if a summit of all-powerful goddesses has only temporarily stepped away, soon to return to issue their decree. They’re implicitly off somewhere, judging you.

The best in contemporary Chicago criticism finds glee in her use of genitalia. In her 2018 essay, “Cunts: 1974–1976,” Johanna Fateman describes a fragment of allegorical drama from the video record of Womanhouse. The play is by Chicago and is called Cock and Cunt. It stars “a young woman in a black leotard, a bubble-gum pink vinyl vulva the size of a dinner plate pinned to her crotch, confronting an identically dressed performer who flaunts a matching stuffed dick.” In exaggeratedly singsong voices, Fateman writes, the “cunt asks for help with the dishes and the cock, by way of refusal, launches into a stern explanation of the natural order. The cunt should wash dishes because it’s round like a dish; the long, hard cock is meant for war-making and missionary-position fucking.”

That Cock and Cunt is hilarious rather gives the lie to the critics who called Chicago poe-faced and didactic. There was more tonal range in her art and in her ideas on gender than ended up getting expressed in her more “serious” and community-oriented later works in textiles. The idea of a trucker driving a vehicle with ovaries painted on it, or the notion of Margaret Sanger chatting away with the goddess Kali over a starter salad, is also funny. Humor, where it exists in Chicago’s oeuvre, leavens the ideas and gives them life; where her humor fails, the work does, too, and the abyssal gap between movements in feminist politics seems to yawn hungrily open.