The story goes that the lyrics to “Black and Blue,” the jazz standard popularized by Louis Armstrong, were written at gunpoint. In 1929, the songwriter Andy Rafaz (born Andriamanantena Paul Razafinkarefo, son of Henri and Jennie Razafinkarefo, a nephew of a Malagasy queen in Madagascar and daughter of first African American consul to Imerina, respectively) was confronted by the mobster-bootlegger Dutch Schultz, the main investor in a revue Rafaz had worked on with legendary pianist-composer Fats Waller, called “Hot Chocolates.” Schultz—with a gun pointed at Rafaz’s head—told him the show needed another number, a comedy song about the hardships of being Black, or else Rafaz would not live to write another word. What Rafaz wrote in response was not a comedy but a treatise on the pain of Black existence in a world structured by anti-blackness:

How will it end? Ain’t got a friend

My only sin is in my skin

What did I do to be so black and blue?

It’s sometimes considered the first “racial protest” song (if the definition of a song here is recorded music, discounting the protest inherent to a number of Negro spirituals sung on plantations), and both the story of its creation and the song itself can stand in for particular strains of Black experience. Under great duress—the threat of death—Rafaz produced a profound work of art that unfortunately maintains its relevance.

It also serves as a lyrical linking of two words that contain a world of ideas inside them. “Black” and “blue” are both colors and conditions of being. “Black,” alongside “white,” has been one of the first color words established across languages, describing basic ideas of “dark” and “light.” It’s a term of racial categorization applied to people of African descent across the globe—whether or not those people appear “black” or would define themselves as such—and reflects a status: “Black” is where you find the bottom of economic, political, and social institutions, and the people lumped into this category are subject to dehumanization and exploitation, which has been justified through the cruelest interpretations of law, science, and religion.

“Blue” has been one of the last colors to receive a name in nearly every culture, perhaps because of its rare occurrence in nature; there is no true blue pigment (the sky and ocean appear “blue” to us as a result of how the various colors travel through and are reflected on the light spectrum), and plants can only produce it through the manipulation of other pigments, most often red. “Blue” was not prevalent in human societies until the advent of manufacturing and industrialization—now it polls as the most popular color in the world. Though it may be a recent phenomenon, it has accumulated much meaning as a descriptor, becoming a shorthand for things like masculinity or melancholy. (“Blue is the color of the mind in borrow of the body,” the novelist and philosopher William H. Gass wrote in On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry; “it is the color consciousness becomes when caressed.”)

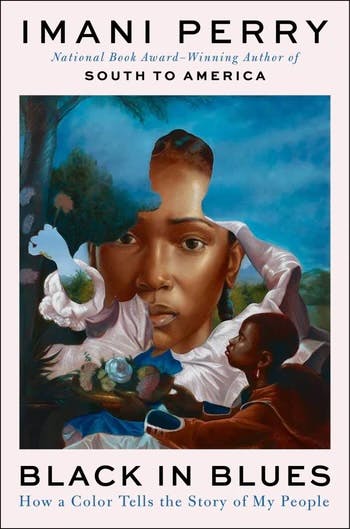

Of course, these are overly simplistic summaries—of the colors themselves, of the ideas they express, and I’ve barely touched the ways in which they have become intertwined. That is the work Imani Perry set out for herself with her latest book, Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People, the follow-up to her 2022 National Book Award–winner, South to America. Perry’s idea, as the title suggests, is that there is such a rich connection between Black people and “blue” that it’s possible to look across time at various pieces of art and artifacts, literal and metaphorical blues, and come away with a narrative of Black people, one that points back to Rafaz’s question—“What did I do to be so black and blue?”

The beats of Perry’s story are not unfamiliar; Black in Blues does not position itself as revisionist. What’s compelling, when and where Perry peers inside of the familiar, through her black and blue lens, to provide us new ways of looking at it, is that the two concepts have become inseparable. “Everybody loves blue. It is human as can be,” she writes. “But everybody doesn’t love Black—many have hated it—and that is inhumane. If you don’t already, I will make you love it with my blues song.”

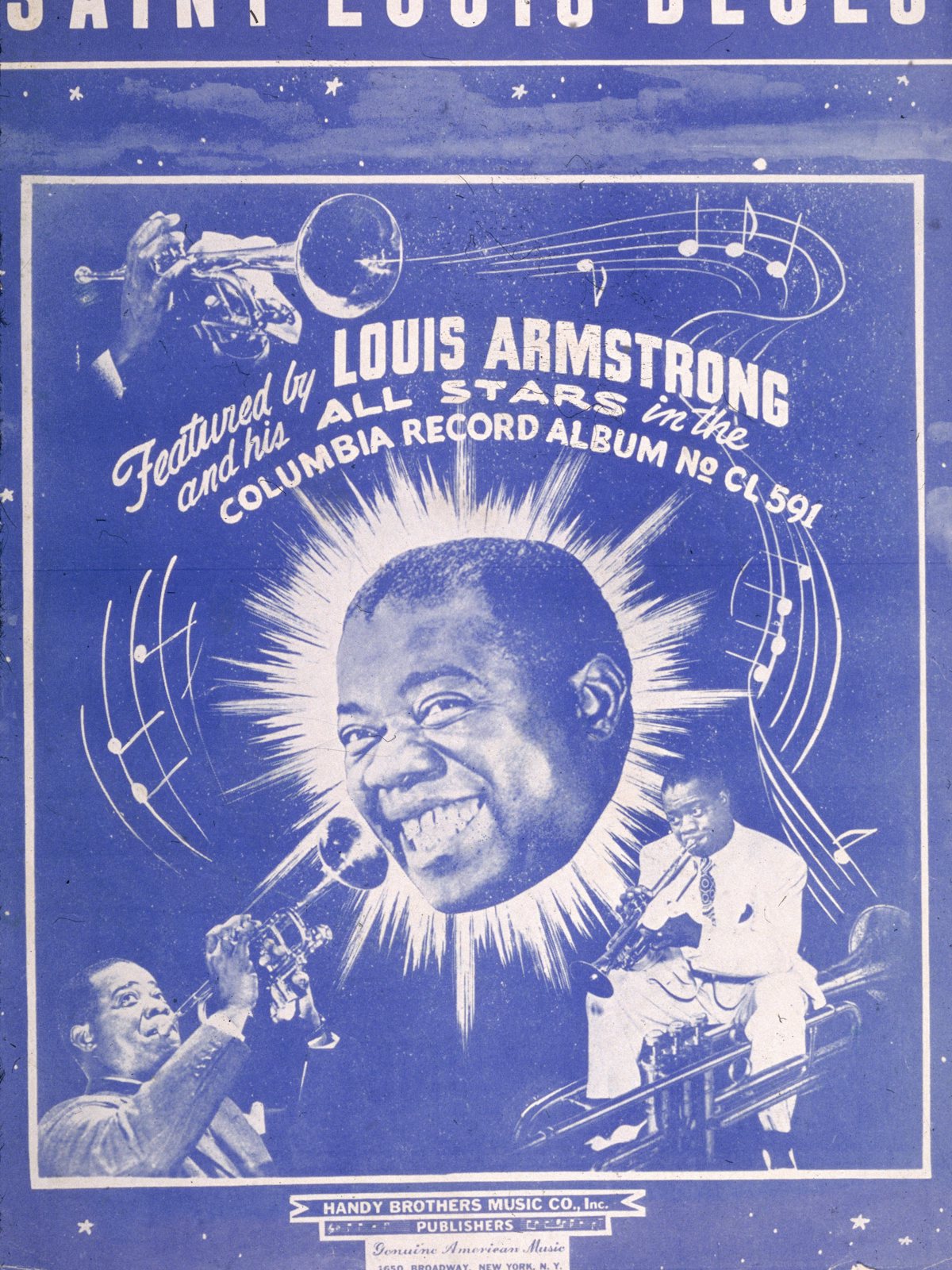

It feels only natural to begin an exploration of the relationship between “black” and “blue” with blues music—the backbone of U.S. popular music, a ready-made metaphor for the Black American experience. Amiri Baraka christened us a “blues people,” after all. And Perry gets to this well-trodden territory, but not without first winding us through a more ambitious historical project.

There’s the transatlantic slave trade, of course, but where many accounts focus on the tobacco or sugarcane that made it profitable, Perry points us toward another lucrative commodity: indigo. Blue may not be abundant in nature, but there are ways of making things blue. The Europeans were using woad as a dye, and indigo, prevalent in West Africa, was the “most resilient and potent of them all,” a fact that did not escape the notice of the slave traders. “The indigo trade is an early and clear example of a global desire to harness blue beauty into personal possession,” Perry writes. Thus our inciting link—black and blue as commodities to be traded and possessed.

It would be easy (and depressing) enough to go from here through a tragic history of black and blue interactions—we live in the era of “Blue Lives Matter,” where police are recast as the “blue” people, worthy of having their lives protected while they terrorize others. The counter-slogan “Blue Lives Matter” “contrasts Black life with police survival—one must choose, it implies,” Perry writes. Interspersed in this lineage from slave trade to modern policing: the fear of “blue-gum Negroes” (exactly what it sounds like—Black people whose gums appeared blue); the blue paper cone that held the sugar Billy Blue stole, which led to his being shipped from London to Australia in 1801; the now iconic Tiffany blue box that held the diamonds mined by South African laborers; Pecola Breedlove’s conviction she has been gifted blue eyes in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye—it all adds up to a sad sack of a blues song.

Which would adhere to the popular understanding of blue and the blues: sad people singing sad songs. It would also be a misreading, or rather an overlooking, of the ways the color and the music figure into Black life. “The blues … articulated a new valuation of individual emotional needs and desires,” Angela Davis writes in Blues Legacies and Black Feminism. There was newfound freedom in the romantic and sexual realms, she notes, which found expression in the blues. They served the purpose of exploration and distraction. “Blues music of its very nature and function is nothing if not a form of diversion,” as Albert Murray put it in Stomping the Blues. It “almost always induces dance movement that is the direct opposite of resignation, retreat, or defeat.”

And so it is with the color too. “We have looked to the blue expanses of even our most treacherous of landscapes as places of possibility,” Perry writes, “the North Star in the midnight sky, which led the enslaved to free territories; the celestial morning blue, which somewhere out of sight housed the gates of heaven and relief from endless labor.” Through a number of examples—blue beads carried by the enslaved on the ships taking to the “New World,” the blue candles burned in the casting of hoodoo spells, the blue uniforms of the Union soldiers whose victory marked the end of U.S. slavery, the “Egyptian blue” paint George Washington Carver created through his own ingenuity, the blue flag with gold star raised when Congo Free State won its independence—Perry asks us to see Black people’s relationship to the color blue in its spiritual and material specialness, and though blue carries immense tragedy inside of it, neither black nor blue is wholly defined by the cruelty that links them. Like a blues song, the beauty is found when you tune into its complex frequencies on the backbeat.

Left unexplored in Black in Blues is the question: Why blue? Other colors make appearances—red, green, yellow—and all could likely serve as the literary anchor; Black life is colorful. The connection to blue is undeniable, as Perry shows time and again, but in a way taken for granted. Early on she recalls asking an elder in Little Rock, Arkansas, why she painted her house a bright blue. “That’s the color it was,” was the reply. And that’s that.

Black and blue are conjoined; this is a book about the how, not the why. “I didn’t want to write an exegesis on blue,” Perry writes, “I realized I wanted to write toward the mystery of blue and its alchemy in the lives of Black folk.” Such is her prerogative, and the book doesn’t suffer any great loss because of this. It accomplishes the author’s goal—this is what any criticism must take into account—of stitching a black and blue quilt with intricate streams, fresh and well-worn patches, to craft a story worth retelling.

Still, and particularly if you are familiar with Perry’s other work, it can leave you feeling a bit wanting, denied her interpretative prowess. Why blue? Here, Gass, again:

Of the colors, blue and green have the greatest emotional range. Sad reds and melancholy yellows are difficult to turn up. Among the ancient elements, blue occurs everywhere: in ice and water, in the flame as purely as in the flower, overhead and inside caves, covering fruit and oozing out of clay. Although green enlivens the earth and mixes in the ocean, and we find it, copperish, in fire; green air, green skies, are rare. Gray and brown are widely distributed, but there are no joyful swatches of either, or any of exuberant black, sullen pink, or acquiescent orange. Blue is therefore most suitable as the color of interior life. Whether slick light sharp thick dark soft slow smooth heavy old and warm: blue moves easily among them all, and all profoundly qualify our states of feeling.

Blue is the only color capacious enough to, on its own, hold inside of it a full human experience. It’s no wonder Black people are continually drawn to it, then: Blue has the ability to express what we have been denied.