“My grandfather’s death, six months into the pandemic, is more than a tragedy,” Sarah Jones wrote at New York magazine, where she is a columnist, in late 2020. “His fate is as political as it is biological. And I am furious.” In her fury, Jones was unusually clear-eyed about the forces perpetuating an infection that mainly killed the poor. Americans were not just up against “a few men without masks,” nor even Donald Trump, “the president who encouraged them,” she wrote. Rather, we faced a system that denies wealth, protection, and care to a vast underclass of people, rendering them disposable.

That system and its dehumanizing toll are the subjects of Disposable: America’s Contempt for the Underclass, Jones’s incisive new book expanding on her 2020 essay. In the tradition of Barbara Ehrenreich, she combines interviews and firsthand observation of poverty with deeply researched history. The devastation of Covid-19 is nothing new, she contends. A reactionary politics has long prioritized the profits of the ruling class while using up the lives of the working poor. Against official indifference, she recounts the stories of people living on America’s margins. Many are family of the Covid dead, people like her who barely got to say goodbye to a loved one who caught the virus at a nursing home or front-line job. “Working-class death can be less likely to claim our attention,” Jones writes. “Their lives and their loves pass away with them, as they move from shadow to shadow. But disposable people have something to say.”

The book feels especially relevant as Trump returns to office. It focuses on the depths of social inequality that the pandemic revealed on his watch, which did not vanish as Americans stripped their masks, returned to eating indoors, and did their best to forget about the virus. A new Trump administration poses unique threats to the welfare state, from gutting the coverage of the Affordable Care Act to slashing housing assistance to reducing SNAP food benefits. But neither major political party has adequately addressed the immiseration that Jones chronicles. Poverty is a fundamental feature of the American political economy, regardless of who’s in charge.

In recent years, books like Steven Thrasher’s The Viral Underclass and the edited volume After Life have approached this problem, with broad-ranging analysis of the legal, racial, and medical histories that make marginalized people vulnerable to viruses. At a glance, Disposable may seem to tread familiar territory, but the intervention it offers is distinctive: a full-throated, class-first critique of how the right-wing tendencies of American capitalism made the pandemic so devastating for the working poor.

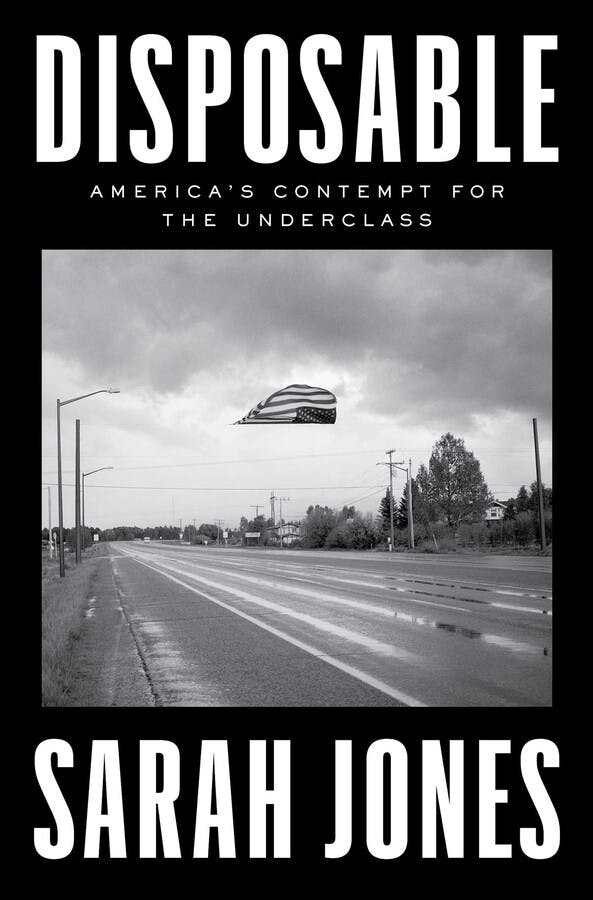

Dominating the book is an image of institutional space, beige, concrete, and lightless: the warehouse, the hospital, the shelter, the prison. These are the troubled domains of the American poor, whose lives the country has sold cheap.

For Jones, that understanding begins at home. She grew up poor in Virginia, and while her family’s economic mobility improved over the years, they were not mobile enough to avoid hardship. “We spent much of my grandfather’s last year on earth navigating an elder-care system that was not designed to ensure his survival,” she writes. He was one of 60 million Americans who bought a Medicare Advantage plan, a predatory scam that offers insurance far worse than ordinary Medicare. Capricious coverage led her grandfather’s treatable illnesses to worsen, and Jones’s mother became his caretaker, ferrying him to appointments on top of her full-time job. In 2020, he cycled in and out of short-term rehab facilities, and that’s where he caught the virus. He died, like so many others, Jones writes, “in a small, cold room, separated from everyone he loved.”

Many lacked even the modest advantages that Jones’s grandfather possessed. People with disabilities faced heightened exposure to Covid-19: They suffer high rates of poverty, and 20 percent live in congregate settings. Jones interviews a woman in Indiana named Debra McCoskey-Reisert, who ruefully reflects that her brother Bobby, who had intellectual disabilities, didn’t belong in a nursing home. But the family had no money for in-home care. The infection that swept the state’s overcrowded and understaffed facilities killed Bobby—a consequence, in Jones’s view, of political disregard for the disabled.

To be homeless or incarcerated during the pandemic was to endure further indignities. An occupant of a Brooklyn men’s shelter says that staff stiffened the rules and separated residents from their belongings, including medications. Meanwhile, the city ramped up draconian encampment sweeps that “destroyed property, displaced human beings, and contradicted [official] guidelines.” The incarcerated fared little better. Covid exploded in jails and prisons, where conditions were cramped and unsanitary. In Washington, the prison infection rate was 8.5 times that of the general population in 2021. “In the lives of unhoused and incarcerated people,” Jones writes, “America’s hostility toward its surplus population is undeniably clear.”

Even so-called “essential workers,” on whose productive labor the nation relied, found little help from politicians and the corporations that own them. As early as May 2020, Amazon yanked its Covid sick leave policy from warehouse workers, even as it posted record profits. Grieving survivors of hotel workers and teachers tell Jones that their loved ones were too broke to seek the care that would have saved them. Over 60 percent of low-wage workers lacked paid sick leave altogether as of 2022, according to the Economic Policy Institute. For Black and Latino workers, whom America has historically excluded from wealth creation, virtually all these problems were multiplied. “To be ‘essential’ in the pandemic is to be offered up as a sacrifice,” Jones writes.

Many of these points, while wrenching, are also now well known from other coverage. What Jones brings to this telling is an unflinching focus on American capital, its unholy marriage to the political class, and the way that union has eroded ordinary people’s faith in authorities. At one point, she speaks with a woman who believes that a Trump-supporting, anti-mask relative transmitted Covid to her mother, who died of the virus in late 2020. “The fact that these deaths were politicized, there needs to be work done for healing for us because there’s no trust in the government,” the woman tells Jones. “They allowed this to happen and they continue to. This is a policy choice, just like gun violence. These deaths continue to be preventable.” Moments like this help to explain why so many Americans, from the middle-class precariat on down, align not so much with one political party or another but against government and its systems writ large.

How should we understand the political conditions that render the masses disposable? Reactionary thinking has resurged among the ruling class, justifying an age-old hierarchy: spoils for the elite few and scraps for the toiling many. Those laboring multitudes have historically been a means for capitalists, no matter their party affiliation, to profit. At the same time, they have been a problem to manage. Elite politics has often been about beating back revolt, whether by suasion or violent repression. The pandemic was, in some sense, a new testing ground for both methods.

Disposable feels freshest when Jones is contemplating how Covid allowed the right to mobilize in opposition to collective health measures. The conservative movement’s distaste for government, voiced in the “language of liberty,” made pandemic lockdowns, masking, and vaccine mandates anathema. In March 2020, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick suggested that seniors “take a chance” on their survival rather than “sacrifice the country” by shuttering the economy. Many citizens were persuaded that Covid constraints equaled tyranny.

The president provided the bully pulpit for anti-egalitarian policy: Trump was only too happy to push for a rapid reopening that would tickle the pocketbooks of business leaders while putting the working poor at greatest risk. On masks, he equivocated in classic form: “Maybe they’re great, and maybe they’re just good. Maybe they’re not so good.” His CARES Act relief package gave billions in tax breaks to the country’s wealthiest people alongside its paltry “stimulus checks” for lower earners. “In Trump, the right discovered a mouthpiece for ideas it had always harbored,” Jones writes. “The former president’s hostility to public health uncovered a hostility to the public, period.”

Hostility to the public, of course, has a formidable history in American life, one that Covid only made viral. The book observes a “social Darwinist” philosophy among the ruling class that has long cast the poor as “lowly by nature.” By its logic, if the underclass can’t hack it through “personal responsibility” and the “dignity of work” in the land of opportunity, then elites are not really to blame for their suffering. These attitudes maintain “a specious distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor,” which has served as justification for bipartisan efforts, from Ronald Reagan onward, to gut social welfare spending. Even with the provisions of the Affordable Care Act, for example, our privatized health system often puts vital services beyond the reach of the underclass, placing the country well below peer nations in terms of affordability, access to care, and mortality rates. It all amounts, Jones writes, to “a violent process in which capitalism triumphs over the human being.”

Reading Disposable, I kept reflecting on the obvious: A plurality of Americans voted Trump back into power, despite his disastrous mismanagement of the pandemic and the massive upward wealth transfer it occasioned. Trump still represents an antidote to politics as usual, a “screw you” to the existing system. Whatever threat the president poses to health care, housing, and labor rights—never mind the catastrophic prospect of another pandemic—plenty of people seem to wager that conditions can’t get much worse than they are.

The ravages of our political economy, after all, transcend partisan politics. Joe Biden’s failings, though less emphasized by Jones, clearly bolstered the American public’s perception of political dysfunction. While the economy soared during the pandemic “recovery,” ordinary people remained buried under routine costs of living. And large numbers continued to suffer and die under Biden, due to the government’s retreat from pandemic aid and precautions. After a while, Biden simply stopped mentioning the virus or commemorating its one million American dead.

Commemoration is one straightforward remedy that Jones prescribes. “In a society calloused by capitalism, the act of memory is not only political but radical,” she writes. Remembrance is not her demand alone. Several of the book’s subjects are members of Marked by Covid, an organization that advocates for a national memorial to pandemic victims. Others are labor activists and organizers united in class solidarity to fight for a living wage, universal health care, affordable housing, and other provisions that virtually all wealthy nations take for granted. What’s astonishing is that so many Americans, no matter how marked and downtrodden, remain up for the fight.