Roy

Cooper will be the next governor of North Carolina.

That’s exactly the kind of declarative boast that would never come from the careful Cooper. Yet, as of the fourth week of October, the Democratic chief executive of the Tar Heel State has all but cemented a second four-year stay in the governor’s mansion.

The latest polling has Cooper thumping his opponent, far-right Republican and current Lieutenant Governor Dan Forest, by a commanding 9.5 points, a lead that has remained steady for the past six months. This projected landslide victory is notable in a state featuring dead-heat races for the Oval Office and a coveted spot in the Senate.

There are plenty of reasons for Cooper’s dominance in this solidly purple state. For one, Forest is, as North Carolina historian and journalist Rob Christensen told me, “the wrong kind of Republican” for the challenge. Rather than being a “Chamber of Commerce Republican,” Christensen said, one with more moderate social views who could continue the fiscal policies in Cooper’s proposed budgets, Forest is an extremist in nearly every sense. His ability to appeal to the more moderate voters and donors is nullified by his dedication to saying things like, “There is no doubt that when Planned Parenthood was created, it was created to destroy the entire Black race.”

Cooper, on the other hand, is the living, breathing antonym of controversy. A soft-spoken, salt-and-peppered licensed attorney whose drawl alone tells any born-and-bred North Carolinian that he came up well east of the capital of Raleigh, Cooper never deviates from his path. It’s one that seeks to split the difference in a state home to both a healthy contingency of rural Republican districts and growing, liberal-leaning ones in urban, suburban, and exurban areas.

What’s extraordinary about Cooper isn’t his middle-of-the-road strategy, which has been used by Democrats since time immemorial. It’s that the strategy is working in a state that, like many that came under Republican control in 2010, has become a veritable lock for GOP candidates, thanks to a concerted campaign of gerrymandering and voter suppression. The central question surrounding Cooper’s reelection goes back to his first run for governor: How the hell did Republicans spend the last decade seizing absolute power in North Carolina and still lose the 2016 gubernatorial race?

It is difficult to overstate what a disaster the 2010 election was for Democrats in North Carolina.

In 2008, when the country was in the midst of an economic collapse, North Carolina voted for Barack Obama in the presidential election by a narrow margin of 14,177 votes, with his candidacy driving record turnout and registration rates. But white voters in the state quickly soured on him, thanks to a toxic stew of racism, adjacent birther conspiracy theories, and a backlash to the Affordable Care Act. Polling shows that after Obama’s inauguration in January 2009, his approval rating among Black voters remained steady, hovering around 80 percent, while it nose-dived among white voters. As Public Policy Polling put it that November, the president “has poor reviews from conservatives, men, whites, senior citizens, and people who live in the Triad or mountains,” the latter being two separate but expansive regions: one the home of a small Republican base for much of the twentieth century and the other comprising three midsize cities in Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and High Point.

The Great Recession hit key stretches of North Carolina especially hard. The state’s manufacturing companies had already spent the 1990s and early 2000s outsourcing their jobs, while the agriculture industry continued its transition to mega-conglomerate farming. These shifts left entire farming communities and mill towns without the jobs that had steadied them for decades. The state’s rolling jobs crisis coincided with a series of scandals that embroiled high-profile statewide and national Democratic officials from 2002 to 2010. Most of these cases—like those of Agriculture Commissioner Meg Scott Phipps, U.S. Representative Frank Ballance, state House Speaker Michael Black, and Governor Mike Easley—involved manila envelopes (or their rough equivalent) stuffed with cash. There was also the sordid tabloid downfall of onetime presidential hopeful John Edwards, the great white hope from the mill town of Robbins.

These overlapping catastrophes set up a historical midterm election in 2010. Rural counties that had long been dependably blue went from purple to beet red in the space of a couple of years—and in a state where the rural-urban split by county runs close to 70–30, that meant a new day in the state legislature.

“The Republicans were the ones that were angry,” Christensen said. “Voters were angry, as were their politicians. And so they were the ones motivated to come out in a midterm year.”

The Republicans swept into the General Assembly, easily winning a majority in both chambers in 2010 and a supermajority by 2011, meaning that Democrat Bev Perdue, who rode the Obama wave to the governor’s mansion and proceeded to poll even worse than the president, was rendered effectively useless. What’s more, the Republican takeover came in a census year, meaning they were able to set the new electoral districts and ensure a decade of power. As Michael Bitzer, a professor of politics and history at Catawba College, told me: “All elections matter. It’s just those that end in zero matter the most.”

For eight years, North Carolina was governed by a General Assembly that was as far to the right as almost any legislature in the nation. Whoever your batshit crazy state representative is, I will raise you one Larry Pittman, who compared Lincoln to Hitler, and I will win.

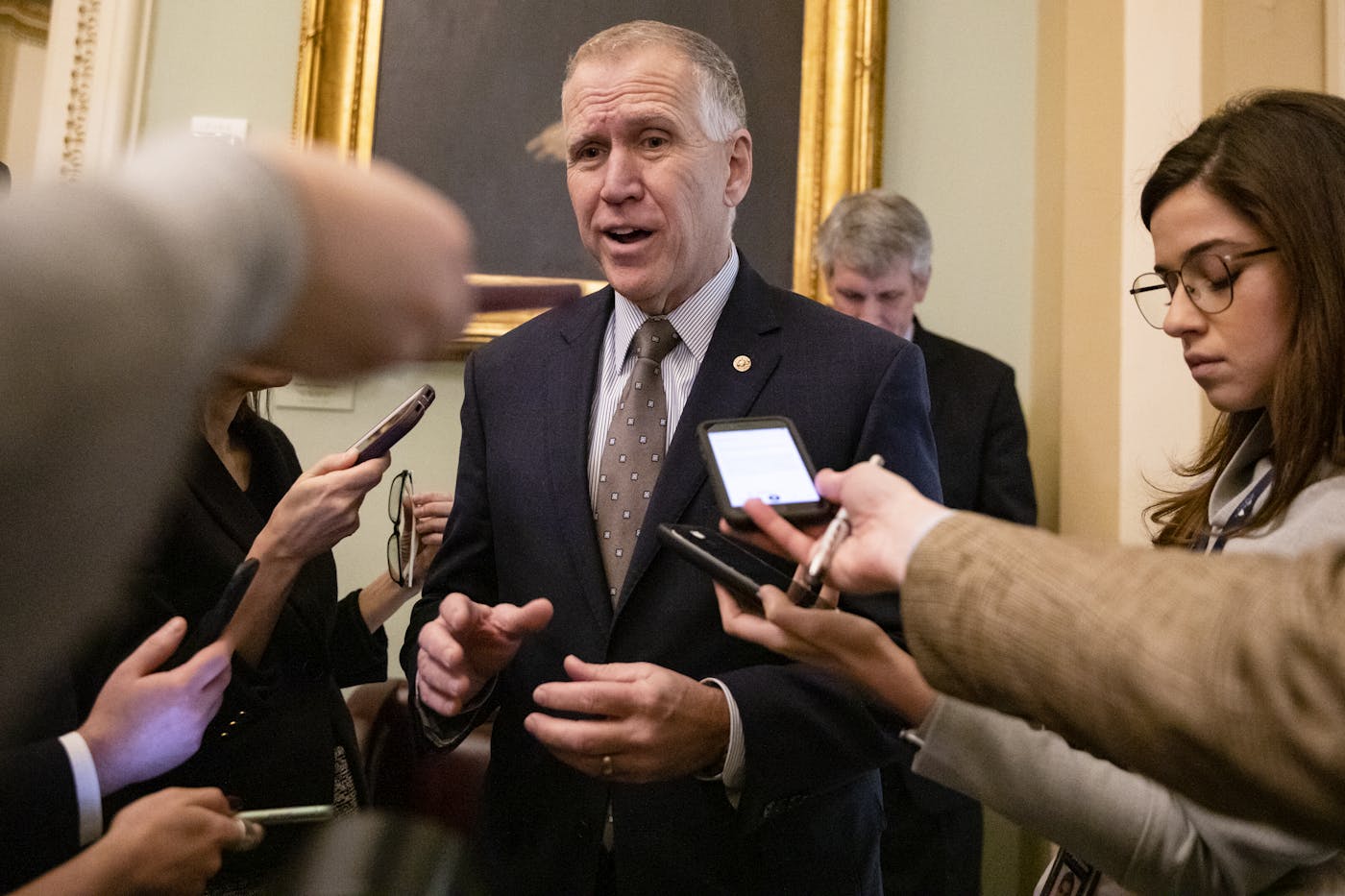

Between 2011 and 2019, Republicans held a veto-proof supermajority in the state legislature, and between 2013 to 2016, they held the governor’s mansion, too. Christensen called the state during this time “ground zero in political polarization.” Led in the Senate by Phil Berger and in the House by now-U.S. Senator Thom Tillis, the Republican legislature gerrymandered the hell out of Black-majority districts, helped pass a gay marriage ban, slashed corporate tax rates, and gutted the state’s prized public education system. GOP lawmakers fought for offshore drilling and defunded the Department of Environmental Quality while hog farms unleashed a literal torrent of shit into state waterways. And they passed a voter ID law that was so egregiously successful at curtailing Black voters that the line used to spike the bill in 2016 by Fourth Circuit Judge Diana Gribbon Motz—“the new provisions target African Americans with almost surgical precision”—has become a fixture in national-lensed political pieces involving the state.

“We haven’t had fair elections and fair districts since 2010,” Durham city councillor and Mayor Pro Tem Jillian Johnson told me. “Republicans were willing to embrace their zealotry and act in completely undemocratic and unethical ways and never really seem to be punished for it.”

Democrats could do nothing but watch a once (relatively) moderate state become a blueprint for modern conservatism’s power-hoarding, rule-by-minority aims. But the silver lining was that the Republicans had a vulnerable governor in Pat McCrory.

Here’s a fun fact: Before he was the governor best known for signing the infamous anti-trans House Bill 2, or the “Bathroom Bill,” in early 2016, Pat McCrory was considered a moderate candidate. Swear to God.

After leading Charlotte as mayor for 14 years, McCrory had established a reputation as a Republican politician who didn’t seem to mind using tax dollars to actually make his city a nicer place to live. In his unsuccessful 2008 bid for the governorship, he actually had to prove that it was his administration, not that of Perdue, the Democratic candidate, that would be harsher on undocumented immigrants. He chose to be a moderate Republican because, up to that point, moderate Republicans, just like moderate Democrats, consistently had the best odds of winning city- and statewide elections. (Jesse Helms is the obvious outlier here.)

North Carolinians, by and large, are not extremists—and they certainly do not enjoy being portrayed as such on the evening news. Responding to a 2018 Gallup poll, 39 percent of North Carolinians identified as conservative, while 33 percent answered moderate, and 21 percent went with liberal. Respondents offered almost the exact same response rates in 2014. But despite this conservative tilt, 44 percent of all North Carolina voters said they leaned Democrat, while 39 percent said they leaned Republican—meaning the state either has a healthy but dormant Gary Johnson fan base, or there are a whole lot of people comfortably sitting on the fence.

McCrory’s problem was that, when he was elected in 2012, his brand of moderate conservatism was out of vogue—not with voters but with the Republican legislature. Berger and Tillis had drawn the maps and tilted them so far in the favor of hard-right Republicans that they knew they could not lose their majority before 2020. They then suppressed the vote further for good measure, and they had the veto-killing numbers, just in case their new moderate governor got any bright ideas. They did not have patience for a halfway-committed executive branch, leaving McCrory in a bind.

“When Pat got to Raleigh, he realized he was a moderate in a conservative party,” Bitzer, the professor at Catawba College, said. “With their supermajority, the legislative Republicans said, essentially, ‘It’s nice to have a Republican governor, to stay the hell out of our way.’ And Pat had to make a decision—was he going to butt up against his own party, or was he going to toe the line?

“That’s where you get the bathroom bill.”

McCrory actually opposed the special session that Republican legislators called in March 2016 to draft HB-2, with top aides telling the press that the governor was concerned the bill would expand to “unrelated subject areas.” The legislation did just that, because Republicans wanted to use this opportunity to ensure that trans North Carolinians had as few legal rights as constitutionally allowable. They didn’t mind the ensuing controversy because controversy is what they and their base—again, not the majority of voters!—thrive on. But by signing HB-2 into law in late March of that year—the bill was hastily turned around by the legislature and the governor in just three days—McCrory cemented his fate. The state was turned into a national punching bag overnight. Concerts were canceled, and March Madness was yanked. And once you’ve messed with college basketball in North Carolina, you might as well pack up your shit.

The saddest part about the McCrory years is that they legitimately did not have to go that way. Before 2012, McCrory was a politician with a specific brand. He was Mayor Pat: a charismatic, business-friendly Republican who had wooed North Carolina voters with his air of pragmatic reasonableness. He chose to capitulate to the governing style of the ardent culture warriors in the General Assembly, and in return they gave him nothing. They stuck him with the label of HB-2 defender even though they were its authors. As Christensen pointed out in his going-away column for McCrory in The News & Observer, the legislature even once used its floor time to publicly ridicule a bill that McCrory’s wife had worked on as first lady that sought to rein in puppy mills. They did not give a damn about this man, and yet he still gave them his career and his signature. He could be wrapping up a second term right about now; instead, he’s hosting a talk radio show.

Cooper was the perfect candidate at the perfect time.

In 2016, Trump was a polarizing figure, and McCrory had soured voters with his moderate-to-wacko bait-and-switch routine. Cooper represented to North Carolinians the most familiar and dependable political face they know: a white moderate Democrat.

“North Carolina has, over the last hundred years, had more Democratic governors than any state in the country,” Christensen reminded me. “More than California, more than Massachusetts.”

It was a little difficult early on to get an accurate read on Cooper’s political viability. Here was a man who, at first glance, looked not too different from Walter Dalton, the Democratic candidate McCrory creamed by 11 points in the 2012 gubernatorial race. Cooper was another middle-aged white guy with two first names and a professional background as a lawyer, looking to jump to governor after serving in the General Assembly and then as a lower-level elected statewide official (attorney general in Cooper’s case), with no identifiable politics beyond being Not-A-Republican. That inoffensive blending-in strategy had doomed both Dalton and Perdue.

But—but!—unlike his predecessors, Cooper was a candidate with a relatively fresh slate. He left the General Assembly for the attorney general’s office in 2000, just before the Democratic Party’s golden age of Tar Heel scandal kicked off. He had been wooed multiple times to run for a higher office, first against Richard Burr for Senate in 2010 and then against McCrory for governor in 2012, and he’d declined both times, deciding to serve a fourth term as attorney general. Given that the administration was still embroiled in the fallout from the HB-2 debacle, Cooper’s position on the periphery of the political scene was a plus for voters in 2016.

It also helped that he had not just a clean record as attorney general but a sterling one. In 2010, the same year Republicans rushed into the General Assembly, Cooper ordered an audit of the State Bureau of Investigations that turned up more than 200 cases in which distorted or withheld evidence led to potentially erroneous convictions.

And since Cooper had been tapped by the party establishment, he faced essentially no competition in the primary, sailing past 71-year-old Kenneth Spaulding by 37 points. In the general election, he played well as a candidate in the exact areas he needed to.

“The dynamics have really shifted in this state to become an urban-suburban-rural dynamic,” Bitzer said, explaining how Mecklenburg County, home of Charlotte, used to be what he called the onetime “base of the Republican spine.” The spine ran north along Interstate 77. But in recent years, as Charlotte has grown, so too have its politics. With one of the highest rates of millennial newcomers in the nation and a median age of 34, the city and its surrounding suburbs, which went to McCrory in 2012, thought better of it in 2016. Unlike Dalton, Cooper attacked the urban and college districts, easily scooping up both Mecklenburg and Wake County—home to Raleigh—and almost all of the 14 rural counties in northeastern North Carolina that make up the 1st congressional district.

Cooper’s 2016 victory was anything but guaranteed. North Carolina, as Christensen pointed out, historically fields some of the tightest elections in the nation. But as North Carolinians voiced their approval for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, the same voters quietly, and narrowly, rejected their Republican governor—the first time an incumbent had lost since the rules were changed in the 1970s to allow back-to-back terms. The state went for Cooper by just 10,000 votes.

From the outset of his term, Cooper was dealing with a steady dose of Republican interference. McCrory held out for a month before conceding the election. Looking to show the new governor the ropes, the General Assembly quickly passed legislation during an emergency session in McCrory’s lame-duck final month that stripped the soon-to-be governor of appointment powers that were fully available to his predecessor.

Cooper was then hamstrung in his first two years in office by the Republican supermajority. With their ability to override any veto from the governor, that legislative weapon became less a last defense than a political prop. True, Cooper’s veto power was not entirely useless, insofar as he forced the GOP to double down on heinous legislation, including the aforementioned voter ID bill, another rolling back water protections for the Outer Banks, and a “born-alive” abortion bill meant to chip away at abortion rights in the state. These calculated showdowns then permitted his press shop to trumpet the extremist agenda of the General Assembly’s right-wing leaders. But this was not how governance was supposed to work. This was politics, with Cooper trying to fend Republicans off long enough to make it to the 2018 election.

In a full term, McCrory vetoed just six bills brought to him by the legislature; Cooper racked up 28 in less than two years. Twenty-three of these vetoes were overridden, but Cooper made his point: He would not be a rubber stamp. He used this period to hit the campaign trail for candidates running for the legislature in the 2018 midterms, tapping into a pool of liberals and moderates boiling with contempt for both the General Assembly and the president. When Election Day finally arrived, the strategy paid off. Although Republicans still maintained their majorities in both chambers, their supermajority was killed—overnight, Cooper’s veto reverted from prop to weapon.

The past two years haven’t featured some miraculous turnaround for the state. Republicans still rule the roost; they just don’t have the freedom they enjoyed in prior years. As a result, Cooper has to be strategic about where he picks his battles. One critical fight has been over Medicaid expansion. North Carolina is one of 12 states left in the nation that has yet to accept federal funding provided by the Affordable Care Act to expand the Medicaid program in the state. (Surprise, surprise: McCrory actually joined the legislature in blocking expansion efforts in 2013.) As a result, nearly 13 percent of all North Carolinians, or roughly one million people, do not have health insurance when they could have it tomorrow, if the government just took the money—a fact that Cooper has underscored throughout the pandemic, featuring expansion as part of his recent budget proposal.

Cooper’s also waging a high-profile fight over public school funding—and the state budget more broadly. The austerity policies of the Recession-era legislature gutted the state’s school systems, and despite the state bouncing back economically (prior to the pandemic) the per-capita funding levels are still well below their pre-recession rates. Teachers and students alike have spent the past few years storming the state capitol to demand more equitable funding, only to be called “union thugs,” even though by North Carolina law, public employees cannot unionize. In 2019, Cooper vetoed the legislature’s two-year budget, citing the lack of Medicaid expansion and adequate raises for public school teachers, leading to a months-long political stalemate.

Now Medicaid expansion and funding public schools are both widely popular positions. Cooper might have moonwalked into a second term on these issues alone, along with underscoring the need to break the Republican majority. But one of the biggest reasons he is dominating Forest is because of his performance during the pandemic.

Of the Southern governors, none has been more adept in their handling of the pandemic, from both a public health and political standpoint, than Cooper. Granted, that’s a low bar to clear, given his company includes Brian Kemp and Ron DeSantis, who collectively have overseen a million infections and 23,000 deaths in Georgia and Florida. Still, Cooper has done more than the bare minimum. Even though his state was reporting low positivity rates in mid-March, he moved to implement safety protocols, including closing in-person businesses and public services, at the same time as New York, where the death rate was skyrocketing. And despite constant pokes and prods by conservatives as the weeks bled into months and the pandemic consumed the summer, Cooper has thus far held steady, prolonging the reopening stages for businesses and schools alike throughout the fall.

“The thing that has always impressed me with the polling on the coronavirus is the hesitancy of a pretty healthy majority of North Carolinians, who are skeptical of widely reopening the state,” Bitzer said. “There is a vocal minority epitomized by Dan Forest that think everything is socialism and the government is taking over everything and we’re destroying the economy. But that number has really kind of stayed around a third. Maybe sometimes in the low 40s. But it’s decisively against a majority.”

Forest’s chances at unseating the steady-as-he-goes Cooper were always slim, but since he’s embraced the identity of a militant no-masker they’ve gotten even worse. For going on seven months, Cooper has appeared regularly on the daily and nightly news of North Carolinians, providing them updates and a steady voice to follow. Despite repeated attacks lobbed against him by President Donald Trump, including a threat—rendered toothless by the pandemic’s spread—to pull the Republican National Convention from Charlotte, Cooper has yet to blast back at the GOP for its scandalous incompetence in handling the pandemic. The closest he’s come is when he quipped that “the federal strategy” on the pandemic “has been nonexistent,” and even that was preceded by two compliments of the Trump administration.

Call it taking the high road or the cautious politics of a man who knows all he has to do to win is keep breathing. Either way, it’s working.

When Cooper is elected to a second term, it will be worth celebrating the fact that Dan Forest or another Republican loon will not be North Carolina’s next governor. But Cooper’s success says a lot more about the extremism of the Republican Party—which has gone so far over the edge that it managed to break its own stranglehold on the state’s vote—than it does about Cooper himself.

Cooper’s 2016 election was heralded as the triumph of a coalition of liberal whites, the state’s Black and Latino voters, and Never-Trumpers. And it was. But Cooper was never a champion for any of those groups. He is a pragmatist, not an ideologue.

Cooper, a proponent of taking legislative action against climate change, didn’t try to stop the Atlantic Coast Pipeline by Dominion and Duke Energy running through Native lands, despite the objections by two of the state’s tribes, as long as it meant he got to boast about jobs and tax revenue. He even went out and hired one of Dominion’s former petroleum lobbyists as his legislative director, only to see the project shuttered.

Cooper grew up on a farm in Nash County and knows full well the rigors of being a farmhand. But he still chose to sign a corporate-backed bill in 2017 that kneecapped unionization efforts by H-2A visa workers, seasonal employees flown and driven in from Mexico who make up a major segment of the state’s farm labor force. He did this against the wishes of farmworkers, which led to him and the state’s attorney general being sued and a federal judge declaring the bill unconstitutional.

Growing up in North Carolina in the 1990s and early 2000s, in a district that has been deeply red, I’ve only known one kind of Democrat when it came to statewide leaders. Cooper fits that mold. So does Cal Cunningham, who is running to unseat Tillis. And in truth, this is more my problem than it is theirs. As Christensen told me, “The state is not liberal by any stretch of the imagination.” This is why, in both 2016 and 2020, Cooper has been the Democratic candidate who best fits the state’s center-right political profile.

But this also means Cooper, for all the relief his success brings Democrats, can’t really be seen as a model for the future of the party, if only because the problems facing North Carolina and the country are too urgent.

There are alternatives, such as Jillian Johnson, who is now serving as Mayor Pro Tem on the Durham city council. In the five years since Johnson was prodded by local grassroots organizations to run for office, she has gone from being the sole leftist vote on the city council to regularly commanding a majority vote in the chamber. The city council has since raised the minimum wage for city workers to $15 an hour; implemented participatory budgeting, a program that lets people directly decide how to spend a percentage of the city budget; passed a $95 million housing bond, the largest in the state; and taken steps to meaningfully address police brutality and the overreliance on police departments for public services.

Politicians like Johnson represent a different kind of strategic thinking. If the state’s Democratic establishment sees the pre-2008 status quo as the goal, then it can’t feign surprise when another version of the 2010 GOP monsoon swiftly follows.

“Before the right-wing takeover, I was standing outside of the General Assembly with a picket sign demanding the right of public workers to collectively bargain,” Johnson told me. “The Democrats were not leading some sort of progressive state agenda. They were centrists. Now, I’d certainly rather fight centrists than the far right. But I don’t have any illusions that the Democratic Party regaining power will put an end to these really intense legislative fights. I’m still going to push the kinds of policy changes that I want to see for people in North Carolina.”

Roy Cooper has been an unexpected blessing in a state that has otherwise gone in the wrong direction these past 10 years. I just hope that his success does not limit who the party backs in the future.