The natural geography of Pennsylvania is not extraordinary. Its major cities are situated near rivers, and it has mountains and miles of punishing greenness. As a shape, Pennsylvania is a rectangle, one of only three of the original 13 colonies to be constructed so rationally—no ragged coastline, no islands. But its political geography is fraught, craggy with sharp oppositions. In 2020, to identify as American is easier, conceptually, than to say, “I am a Pennsylvanian.”

The metropolitan-rural divide asserts itself fiercely. Residents of its two major cities, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, often feel beset by its state government, which is overwhelmed by rural representation. In addition, the cities are less major than they used to be: Philadelphia is large but shrunken from its peak size; Pittsburgh’s population lies at a little over half its midcentury high-water mark. (Philadelphia’s population only stabilized in 2007; Pittsburgh’s is still declining.) Many of the state’s other cities, tied to industries that have either become less labor-intensive or fled, have endured severe drop-offs in population and investment.

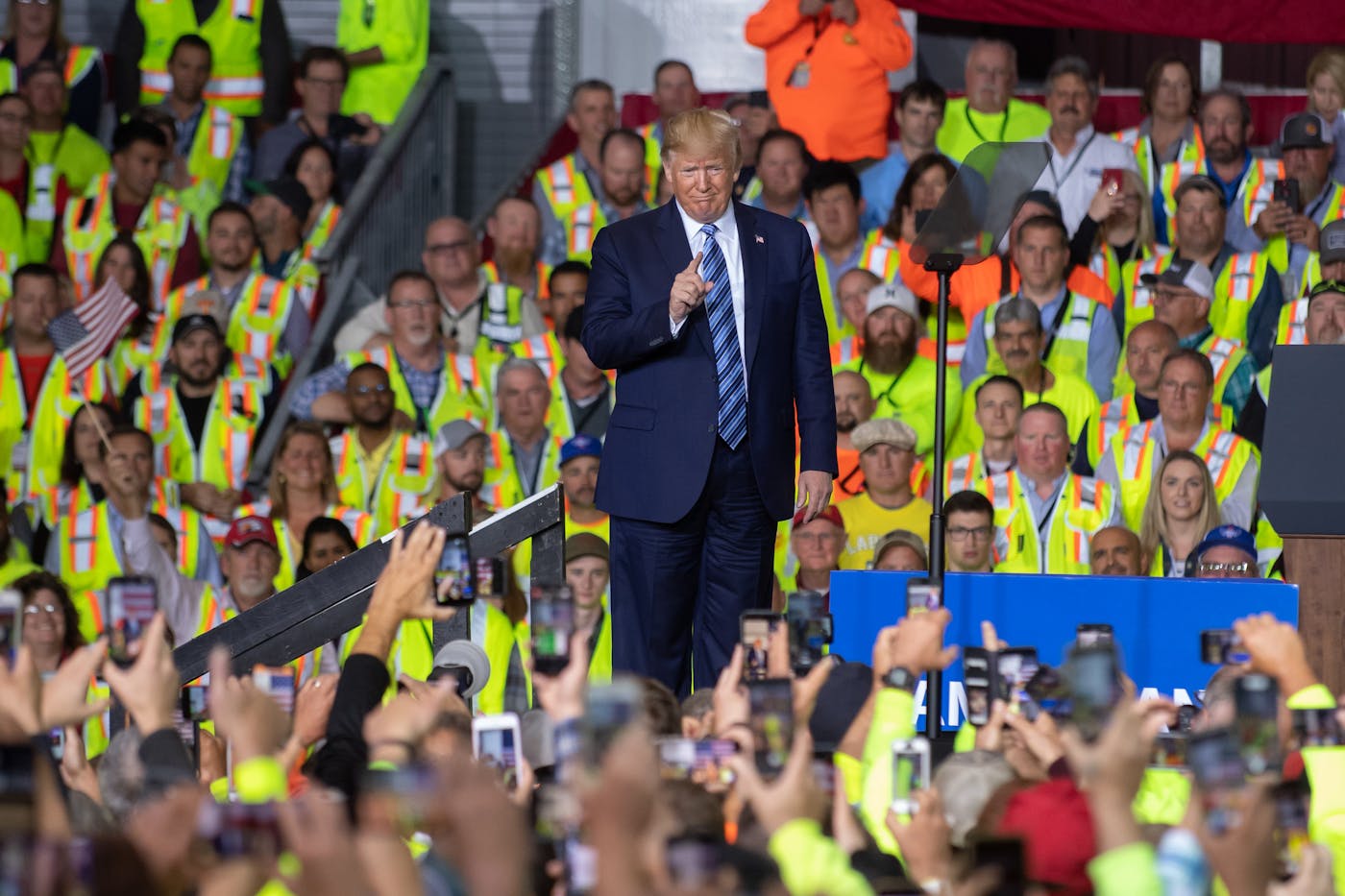

Fifty-eight percent of the state is forest; nearly a third of its residents live in rural counties. In them, you will find support for President Trump and right-wing reaction as intense as in any region in the country. You will also find anti-Trump organizing that is growing in strength—if not quickly enough to stop Trump from carrying those counties in November.

Between city and country lies a more variegated landscape of intermediates. Travel in just about any direction from Center City, Philadelphia, and you begin to find yourself in the “collar counties”—the Philadelphia suburbs, a mythic landscape that political journalists have interpreted as bellwethers of American political trends. In recent years, those suburbs, redoubts of a middle- to higher-income Republican electorate, have been completing a years-long shift to the Democratic Party, reflected in congressional, state, and county legislative victories.

An equal part of the Pennsylvania electoral mythos is in the west, where Appalachia rears up; where the steel mills are shuttered but the exurbs they built are white and increasingly conservative. And cutting a broad swath from the northeast in a pointillist smear down to its southwest are clusters of Pennsylvania’s 7,000 or so active natural gas wells. Since the late 2000s, fracking has transformed the state and the rest of the country along with it. Pre-pandemic, Pennsylvania was slated to be the second-largest extractor of new oil and gas in the country.

If I sound like an alien confronting an unfamiliar landscape, it is because, in part, I am one. I am the Democratic nominee for state Senate in the First Senate District, which encompasses much of Philadelphia, but I only moved here nine years ago, an Indian-American and a non-Philadelphian. Among major cities in the United States, Philadelphia has one of the most stable populations: According to a 2016 Pew study, it was ninth among 10 major cities in terms of incoming population. At the same time, its historical imagination is clannish. As the sociologist E. Digby Baltzell pointed out long ago, in Boston it was common to note where you went to school; in Philadelphia, to mention who your father was. “Philadelphia is a conservative city,” he wrote, suggesting that “social connections there are perhaps more important than elsewhere in America.” Many of the political names currently active in the city can be connected to still-living parents who recently held administrative or political office.

During the primary election earlier this year, a former state senator for this district, Vincent Fumo, called for me to “go back to the Socialist Party and to NY.” I am neither a member of the Socialist Party nor from New York, but Fumo’s perception of me as an outsider, and his attempt to delegitimize me as one, could have been resonant. But it wasn’t, or not resonant enough. Some 230,000 Philadelphians, at last count, were foreign-born: They are the primary reason that the city is growing at all.

Philadelphia is, and is not, Pennsylvania. Forty-two percent of Philadelphians are Black, but only 12 percent of Pennsylvanians are. More than 80 percent of Pennsylvanians are white. Philadelphia is a “sanctuary city,” a status repeatedly challenged—in law and through force—by the federal government and within Pennsylvania. The state ranks sixteenth among states in the population of undocumented immigrants—but, when it comes to the number of undocumented immigrants arrested without criminal records, it is first. Agents based in Philadelphia, their numbers bolstered by Trump’s obsession with the city, fan out and trap immigrants on the highways.

This is an election year, and short-term incentives align around heightening the distinctions between Philadelphia and Pennsylvania. For Democrats, winning right now means driving up the score in Philadelphia and the suburbs, while peeling off a handful of votes elsewhere. For Republicans, it means casting “Philadelphia liberals” as dangerous outsiders undermining our state. It will feel, especially if Trump wins again, as if the city is trapped in a state that despises its existence. But a future for the state, as well as for the rest of the country, lies in overcoming these oppositions. It lies in finding a formula that unites disparate causes across Pennsylvania—a formula that goes against the grain of mainstream Democratic thinking on issues like the environment and economic development.

During the bribery scandals known as Tangentopoli in Italy in the 1990s, the rallying cry was for “un paese normale,” a normal country. Something similar could be said of the feeling in Philadelphia. For years it has borne ignominious statistics: the poorest major city; the most incarcerated major city. It is corrupt: The last three state senators to have held the seat for which I am now the Democratic nominee have been federally indicted. Row offices that elsewhere are technocratically administered and appointed, such as election commissioners and the register of wills, are elected here, politicizing normal city operations. Philadelphia has a strong array of good-government groups—the urbanist PAC 5th Square; the reform-oriented electoral organization Philadelphia 3.0; and the nonpartisan Committee of Seventy—which stand in proportion to the city’s high level of bad government.

The city’s Democratic Party, structured by a ward boss system like Chicago’s, is one of the country’s last great urban machines, running the table in municipal elections and doling out patronage. Lawyers do work for the party for years and receive judicial endorsements as gratitude; favored committee people and ward leaders end up with city and state jobs. In election years, endorsements are traded among factions. This chess match—in which one candidate is elevated by one faction so that, in the future, that same faction will be obligated to a partner faction to elevate its candidate—is virtually endless.

However, it’s also the case that even describing the city party as a “machine” overstates its ability to function and shape the political playing field. It is, rather, a contraption that consists of various regional machines: Black political machines in the city’s west and northwest, a feuding pair of largely white machines in the city’s northeast, intermittently sparring and cooperating Irish- and Italian-American machines in South Philadelphia.

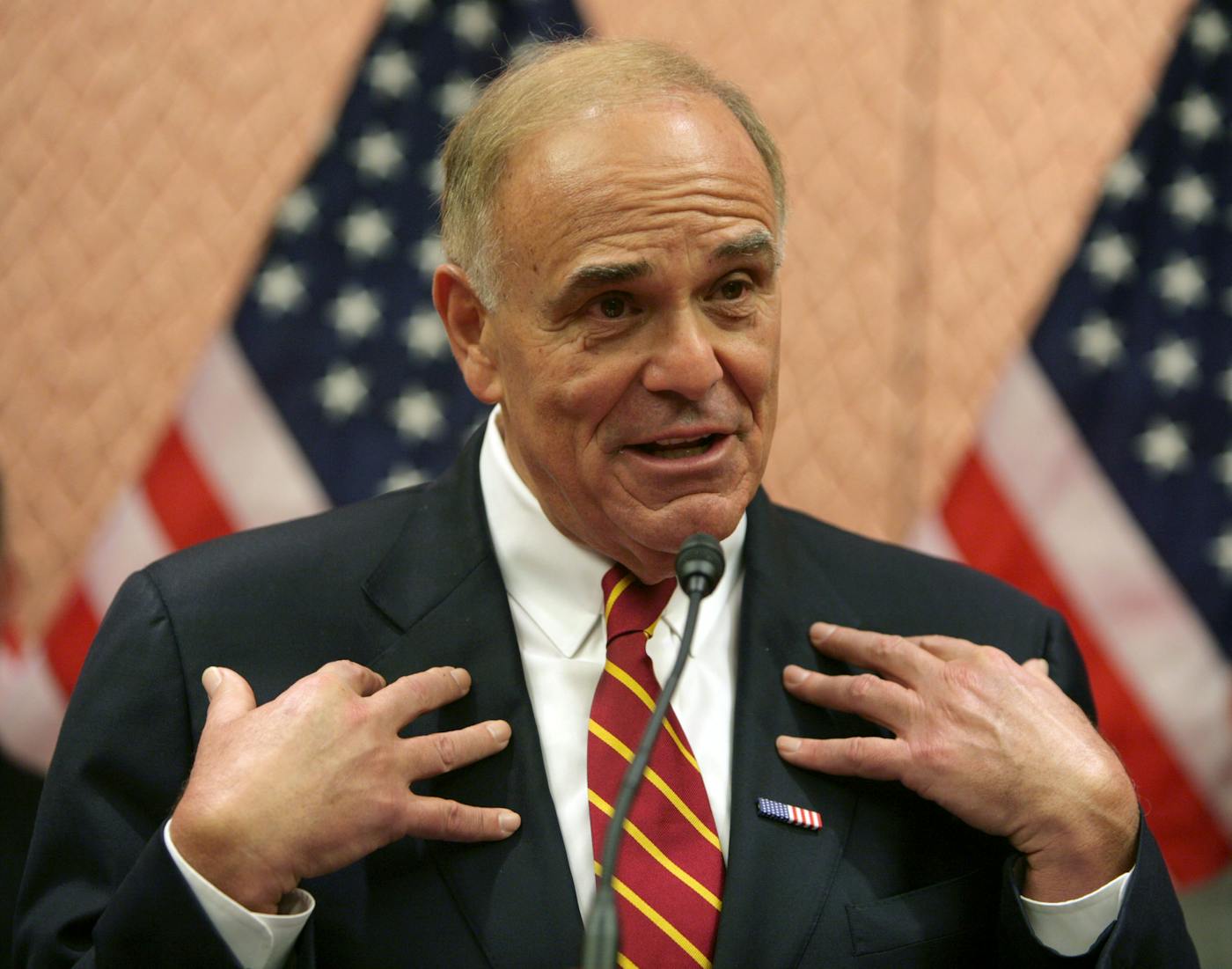

Though I didn’t know it at the time, the city I moved to in 2011 was concluding one era of its development and beginning another. In the 1990s, under Mayor Ed Rendell, Philadelphia moved toward a tourist- and services-oriented model, focusing on bolstering arts institutions and the health care sector, while fighting the city’s municipal unions and beginning the process of converting declining manufacturing hubs, such as the city’s Navy Yard, to office parks. Rendell instituted a 10-year abatement on commercial and residential property taxes for all new and rehabilitated development. A development boom followed, partly as a result and partly following national trends of urban reinvestment. Now a belt of gentrification surrounds the urban core and the city’s handful of major transit hubs.

The process worked on its terms, if at the expense of equitable development in the city. As the city underwent a partial revitalization, many of the new residents allied with existing ones and reformist unions around the deep underfunding and mismanagement of the city’s school district. The tax abatement, in particular, became a target of activists and educators fighting for equitable school funding, since it subsidized developers and homeowners at the expense of public goods: public education, in particular. It was no good attracting residents to the city with tax abatements, only to have them move out a few years later to avoid sending children into school buildings with exposed asbestos and unremediated lead.

In 2013, when the Republican governor cut $1 billion from the state education budget, and 23 schools were closed in Philadelphia, activists began to elevate the tax abatement and local control of schools as a major target. One of those activists, Helen Gym, was elected to City Council two years later and immediately became its strongest voice for reform. At the time, Gym seemed an outlier. She now appears a harbinger.

Much of the politics in the last decade has been consumed by an attempt to create alignments among disparate groups: the increasingly left-leaning and increasingly young new residents, largely white, buoyed by the development boom but also suspicious of it, and the Philadelphia working-class—Black and brown, many of them immigrants—trapped in low-wage employment and unstable housing. A good deal of conversation in Philadelphia revolves around “jobs” and the lack of them. The jobs that exist pay poorly, even in many of the unionized industries. Domestic labor and other forms of care work, such as home health care, are among the fastest-growing sectors of the workforce but are among the most poorly paid.

As in many cities, these two forces—the growth of the left, and low-wage worker organizing—have grown in tandem. The distinction in Philadelphia was the continuing power of the political machines: easier to win over fractions of that machine, or work with them, or dismantle them, than to fight against a fully liberalized city in which business was unchallenged.

In 2016, I was a lead volunteer on the Bernie Sanders campaign in South Philadelphia. I recruited and trained canvassers in my house and sent them out into the field. During lulls in the training sessions, I canvassed packets of “turf” myself, and a few bouts of this left me transformed. There was the rare pleasure of supporting a candidate whose beliefs and policies you more or less espoused without reservation: I could say what I meant. But there was the less expected pleasure of coming to know a shared world, right at my doorstep. Many of my neighbors agreed, or were close to agreeing; many more could be moved. For dozens of us, volunteers and staffers on the campaign, this experience left a powerful imprint.

We kept the gang together and formed Reclaim Philadelphia, filching our name from a sister group in Chicago. (This year, in an attendant spirit of copyleft, a group of friends in Rhode Island created Reclaim Rhode Island.) For a few months, our organization consisted of about 40 or 50 dues-paying members and volunteers. We took up a few causes: We protested the shady financing behind the Democratic National Convention and were arrested; we protested the financing of the Dakota Access Pipeline by TD Bank and were arrested. In the fall, we knocked on doors in Northeast Philadelphia for a state representative candidate, Joe Hohenstein, who was trying to flip one of the last remaining Republican legislative seats in the city, while also making the case for Hillary Clinton. It was tough territory: I remember one conversation where the homeowner, a Black veteran, warned me that sharia law was coming to this country. Forgetting myself, I angrily told him that it was indeed, and that I would be the one to bring it.

On November 8, 2016, I threw a party, the dumbest idea I’ve ever had, where we ended up watching John King on CNN color generous portions of Pennsylvania in red. Even parts of Philadelphia, such as the greater Northeast, and one ward in South Philadelphia, went for Trump. These areas, semi-suburban destinations of white flight, where the union members and their children grew up, are not so dissimilar from the western counties that turned out heavily for the president and will do so again.

A few days later, Reclaim held an emergency meeting. Two hundred people arrived and signed up as members. Suddenly, we were a viable organization. We were also part of the “resistance,” insofar as hundreds of people had joined us because they were opposed to Trump, not because they had supported Bernie Sanders. But in the Philadelphia context, the demands of our group and the demands of a national movement began to converge.

By January 2017, we had played a principal role in recruiting a civil rights attorney, Larry Krasner, to run for district attorney. Once again assembling the Bernie base, and enlarging it by several orders of magnitude to include those radicalized by the depravity of Donald Trump, we knocked on 90,000 doors and helped deliver victory to Krasner—a man who had called policing “systemically racist.” In many areas where over-policing was not the principal experience of the residents, we were able to make a broad argument about the decline of the school system and the investment in jail cells and prisons over education. Krasner won with the support not just of the movement, however, but also of union power—especially AFSCME District 1199c, a majority-Black union of health care workers—and of a key political machine, a group of wards known as the Northwest Coalition: largely Black, working- and middle-class neighborhoods that had seen police brutality and mass incarceration come to their doorsteps. Krasner instantly became the leading face of a nationwide movement to change the aggressive, functionally racist nature of prosecutorial discretion.

In the years since, Reclaim has repeated the formula of finding a winning candidate who is a credible messenger for a movement. In 2018, Joe Hohenstein, who had lost in the Republican wave of 2016, ran again and won; so did Elizabeth Fiedler, a former Philadelphia NPR reporter, running for the first time and beating a candidate backed by the powerful electricians’ union. In 2019, two Reclaim-backed candidates, Isaiah Thomas, a basketball coach and educator, and Kendra Brooks, an organizer for public education and reducing gun violence, won races for City Council on platforms that included a moratorium on charter school expansion and ending the 10-year tax abatement.

Increasingly it became clear that what we could accomplish in city offices was limited. Ending a generous tax abatement would only bring a small portion of revenue to the city. Revamping the funding formula at the state level, which relies heavily on local property taxes and renders Pennsylvania nearly the most unequal state in the country for school funding (only Nebraska is worse), would fundamentally change the picture.

I had entered politics—indeed, machine politics—myself when I won a position as a South Philadelphia Democratic Ward Leader, the first Asian American to do so. On the strength of that work, partly, and also of several years as a volunteer labor organizer with the hospitality workers’ union UNITE HERE, I ran for office with a suite of proposals on housing and a Green New Deal, and with an unexpectedly broad activist and labor coalition, I won.

Two features now define the political landscape in the city. The first is the success of the left in winning a place in city government, albeit a moderate one, without an overarching program that has garnered broad consent. It resembles what the political scientist Richard DeLeon, writing about San Francisco’s politics in the 1970s and 1980s, called an “urban antiregime”: a political coalition committed to defeating forms of development that take place at the expense of public investment, without being in a position to use private enterprise and capital to develop a citywide agenda that it can be at home with.

The second is right-wing control of the Pennsylvania legislature. Though Democrats have been chipping away at this majority over time, we remain short of it. Furthermore, our own ranks are in conflict over charter schools, and housing and zoning. A unifying issue that can broaden the Democratic base and unite the state remains out of reach. Lacking this, there is every likelihood that the primary conflict in the state—between city and country—will grow sharper. One problem that has become a subject of considerable, often tedious debate in the presidential election may prove unexpectedly to be unifying. That problem is fracking.

In a recent article for Democracy Journal, the historian Lara Putnam noted that the critical districts in Pennsylvania for the growth of the Republican Party were “middle suburbs,” many of them found in western Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. “These aren’t the upscale suburbs ringing today’s prosperous major metros, full of cosmopolitan knowledge workers,” she wrote. Putnam traces the history of how a booming steel industry in western Pennsylvania birthed a middle class that moved out of the cities, with their dense associational lives, to prosperous townships. When the industries left in the 1980s, the middle class in these towns nonetheless remained. Even union ties persisted, with many workers organized in public and service sector unions.

But the politics changed. As Putnam notes, western Pennsylvania voted Democratic more reliably through the 1980s: Jimmy Carter won by 10 points, Walter Mondale by 20, Michael Dukakis by more than 25. The shift occurred in the 1990s, when the population also became more rural—or rather, more part of the “middle suburbs.” In 2008, Barack Obama slowed the decline of the Democratic vote share there, before it collapsed, and Trump gained the margin to win the state. “Donald Trump’s gains over Mitt Romney in Beaver, Washington, Fayette, and Lawrence counties alone topped 45,000 votes,” Putnam writes. “He won the state by 44,000.”

Between the elections of 2008 and 2016, another force intervened in western Pennsylvania politics. There are now 30 natural gas wells in Beaver; 257 in Fayette; 1,146 in Washington County, where the first well was drilled in 2004—the most drilled place in Pennsylvania, where Amity and Prosperity, the titular towns of Eliza Griswold’s award-winning book, are located. There are currently nearly 8,000 active natural gas wells in Pennsylvania. When it emerged as a technology, Democrats at every level of government supported the expansion of fracking: Here was a way to reduce American reliance on non-American fossil fuels, to expand American gross domestic product without expanding the American labor force (fracking is one of the most capital-intensive, and least labor-intensive, forms of extraction), and, less importantly, to reduce carbon emissions while leaving untouched the system of fossil fuel–based capitalism.

The distinctive feature of fracking, as the scholars Colin Jeromack and Nina Berman have argued, is its personal nature. Energy firms reach the gas by leasing mineral rights from landowners, who often receive royalties. “In this way, fracking is more intimate,” they write, “more dependent on personal approval (rather than, say, local governments), and potentially offers more direct financial benefits than many other environmentally risky land uses (e.g., a landfill or coal mining).” The history of property rights in the region meant that “landmen” from energy firms contracted directly with families, rather than needing to engage in the public comment process that often accompanies (or stymies) any number of land-use decisions.

Fracking has been a classic case of privatized rewards accompanying socialized risk. Many people have benefited from it; far more have suffered. But the suffering is not the same as that associated with the heyday of the coal industry, which employed thousands in dangerous work. Fewer people work in natural gas; more people benefit through individualized contracts and property rights, and more suffer through the lack of those rights. The aggregate effects of fracking have been enormous, with studies suggesting an increase in methane emissions, a greenhouse gas worse than carbon, due to fracking. Meanwhile, being located thousands of feet from a well pad could still mean that your water, especially in areas with limited water supply, was contaminated. This is to say nothing of pipelines that transmit natural gas, which are strung across the state and have broken and spilled repeatedly.

The immediate effects on families living within a distance of fracking wells can be devastating. In 2020, a damning grand jury investigation of the Department of Environmental Protection and Department of Health detailed just a few:

Then there was the air. The smell from putrefying waste water in open pits was nauseating. Airborne chemicals burned the throat and irritated exposed skin. One witness had a name for it: “frack rash.” It felt like having alligator skin. At night, children would get intense, sudden nosebleeds; the blood would just pour out.…

Many of those living in close proximity to a well pad began to become chronically, and inexplicably, sick. Pets died; farm animals that lived outside started miscarrying, or giving birth to deformed offspring. But the worst was the children, who were the most susceptible to the effects. Families went to their doctors for answers, but the doctors didn’t know what to do.

The imprint of the industry could be seen throughout Pennsylvania’s government, not least of all in the Democratic Party. In 2003, Ed Rendell, now the governor, appointed Katie McGinty as his secretary for the DEP. This was when the shale boom was taking off, and 130,000 acres of public land were opened to drilling (a move that Governor Rendell later said he regretted). From 2008 until her appointment as Governor Tom Wolf’s chief of staff in 2014, McGinty served on the boards of two energy companies and was managing director of a consulting firm that was a member of the Marcellus Shale Coalition, an industry trade group. She then ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in 2016. A Republican Super PAC used the industry connections to attack her in an ad. (I knocked doors for her in Northeast Philadelphia, where people I talked to derided her, in the attack ad’s language, as “shady Katie.”)

With fracking no longer seen as a boon for foreign policy, the economy, or the climate, its basic toxicity ought to be obvious. Yet Democrats ostensibly committed to fighting climate change regularly support subsidies for the industry. Partly this is due to the binding of fossil fuel jobs to building trades unions—many of whose members would work in renewable energy, if there were sufficient will to boost it. Now that fracking is considered even by Wall Street to be in decline, Pennsylvania has doubled down on petrochemical plants that use ethane, a product of fracking, for manufacturing plastic—a way of managing the overabundance of natural gas. Beaver County is the site of one such “cracker” plant, owned by Shell, which received the largest tax break in recent Pennsylvania history, $1.65 billion. Employing 600 permanent workers, the plant reaped $2.75 million in public subsidies per employee. Supporters of fracking worry about lost jobs. But depending on tax credits on this scale to create a relatively meager number of jobs would, in any other sector, not be considered a sustainable business model. As Kate Aronoff has argued in this magazine, the industry is in trouble. Some form of government nationalization and a wind-down is the way to save workers from crashing out of it altogether.

For Democrats, fracking and the fossil fuel industry are seen as complex liabilities to tiptoe around, rather than what they are: polluting, corrupt, dangerous, and unpopular. When two of the leading Democratic presidential candidates, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, announced support for a fracking ban, a flurry of stories appeared signaling danger not only for them but for all Democrats in Pennsylvania should either of them win the nomination. The prospect of a pro-fracking backlash remains so strong that Trump has steadily campaigned on the false claim that Joe Biden himself would ban fracking. The Biden campaign has devoted considerable time to a strenuous and constant objection, when it has a powerful clean energy program to tout.

The fact is that most Pennsylvanians support an end to fracking: A slim majority (52 percent) in a CBS/YouGov survey published in August supports an outright ban, while a sizable majority (62 percent) supports phasing out fracking by 2050, according to a poll from the Global Strategy Group published in August. According to the latter, most Pennsylvanians also favor “bold action” to fight climate change. Permitting fracking to continue unabated is not what they mean.

In Amity and Prosperity, Eliza Griswold’s nonfiction narrative of a western Pennsylvania family fighting the transgressions of a fracking company, the main protagonist, Stacey, begins with mistrust of the government and of “environmentalists” from Philadelphia who deride fracking but rely on its benefits every time they switch a light on. By the end of the book, she has turned against fracking but retains her mistrust of government—exacerbated by the failure of regulatory authorities such as the DEP and the EPA to protect her and her family. No fan of Trump, she doubts the virtues of Clinton: “[W]hen it came to fracking, she was just as bad as Trump, if not as vocal.” Seeing the Green Party slogan, “Protect Mother Earth,” she casts a vote for Jill Stein, one of 16 people in her township to do so. Seventy percent of the 1,861 other voters go for Trump.

The political problem that lingers in Griswold’s book is the fact that many residents of western Pennsylvania have had their lives upended by fracking and do not support it but are in firm opposition to liberal southeastern Pennsylvania residents who are against fracking. The paradox of fracking’s unpopularity, then, is that it does not pose an obvious coalition.

No formula will solve decades of political drift. But organizing is rising to support an alternative future. In addition to the widespread shift in the Philadelphia suburbs, less-heralded changes are taking place in small cities—Lancaster, Reading, Allentown, York, Harrisburg—and the regions surrounding them. Many former Indivisible chapters and analogous organizations have joined a statewide federation, Pennsylvania Stands Up, which is transforming politics in the Lehigh Valley, the Capital region, and Erie. (Reclaim Philadelphia is also a member.) Organizers, many of them of color, have come out of post-2016 groups, and are backing left-wing candidates in these areas previously thought to be conservative strongholds: One of them, Nydea Graves, a prison abolitionist, just won election to the Coatesville City Council. As Lara Putnam has noted, protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder took place in 60 communities across Pennsylvania, where more than half of the Black population lives outside of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, and where many of the smaller-to-midsize cities, often written off as conservative or part of a declining Rust Belt, have majority-minority populations. This sort of work could be the basis for a new statewide coalition, previously thought to be impossible.

A statewide project connecting rural and metropolitan concerns could emerge on the subjects that concern the entire state and that have, on occasion, riven the Republican coalition: schools and the environment. In 2014, Republican Governor Tom Corbett lost his reelection bid after his budget cuts to education drained his popularity throughout the state. Similarly, Republican support of the natural gas industry is ceasing to pay dividends, with the industry in free fall and renewables cheaper than ever.

A Green New Deal for schools, which would focus on complete remediation and retrofitting of educational facilities throughout the state, generating construction jobs as well as maintenance work, would be a start, focusing on transforming the demand-side of the fossil fuel industry. Introducing parity pricing for farm commodities, whereby farmers could be guaranteed a price for their products that includes the cost of ecological management, could transform the state’s agriculture. Agrivoltaics, which would dramatically reduce energy costs for solarizing rural agriculture, would transform farming without requiring giant wind farms to overrun the landscape. The point is to produce a project that has visible results, that brings jobs to rural and urban Pennsylvania, whose benefits are tangible and profound.

Short of this, Pennsylvanians will be trapped in a cycle of deepening disinvestment and rabid polarization—courted by presidential candidates in search of votes but producing no long-term realignment, and offering no sustainable future.