A woman sprawls on a bed, the suggestion of a wall behind her. With her left hand, she cups her left breast, while the right falls free. Her eyes are turned toward the pillow. Her strong thighs don’t quite meet, and her knee points toward a table in the foreground, where a boiled egg, sliced in half, waits in a white cocotte (a morning-after repast, maybe): a visual echo of her bountiful nipple. Lucian Freud called this painting Naked Girl With Egg.

The girl in question is Celia Paul. She was in her twenties when she sat for the painting; Freud was in his fifties. Sure, it’s that old story: the art student and the visiting tutor, a passion we might speak of as forbidden were it not so familiar. In her new memoir, Self-Portrait, Paul, now in her sixties, no longer student but master in her own right, writes of modeling for Freud in the fall of 1980, not long after they’d met and begun an affair that would last nearly a decade. She struggled under her lover’s scrutiny—she recalls that he “peered down” at her, though on canvas the subject’s body looms over the viewer. “I was very conscious of my flesh, and I felt myself to be undesirable.”

Of course, that’s Freud’s work: lush bodies and frank physicality, haunted faces with the suggestion of introspection. We might understand his nude figures as sexual, but they’re rarely sexy. Maybe Paul was just too young to understand that; maybe she thought modeling for her lover—intimacy with a complicated power dynamic—something close to a sex act. “I felt exposed and hated the feeling. I cried throughout these sessions.” She never gives her opinion of the finished work.

It’s probably wrong of me to begin with Freud, though I imagine there will be readers who come to this memoir looking for him. In life, his fame far eclipsed hers—we might call her an artist’s artist. Self-Portrait is not an exercise in setting the record straight, the unvarnished truth about a great man. Nor is it the work of an artist’s muse, speaking up at last. It’s an account of a life so rigorously dedicated to art and family that fame seems beside the point. Perhaps the most telling relationship in the book is Paul’s friendship and then rivalry with another girl, Linda, when she was only 15, both so obsessed with art that they became “secretive and mistrustful of each other.” Self-Portrait documents a woman learning to trust—not Freud, not other artists, but herself.

Celia Paul was born in 1959 in India, where her father was head of a seminary. Faith was important to both her parents. Her mother, frequently Paul’s model, used their sessions together to pray. Paul doesn’t speak of religion’s role in her own life, but I understand art—defined broadly—as the filter through which she sees all, perhaps as total as her parents’ Christianity. As a writer, she’s possessed of a heightened sensibility, a particular vantage on to the world. Here’s her recall of India, which she left at age five:

The drumbeats from the Hindu festivals would echo up to our house across the paddy fields from the Hindu temple in Trivandrum. The drums would be accompanied by chanting and screaming, which would reach a crescendo and then suddenly there would be silence, punctuated only by the lonely howl of the jackals.

This is less a memory than it is the colonial mythology that a woman now in her sixties would have been raised on. Of course, a memoir is as much a construction as a painting. Here are things as I see them: as dramatic, thrilling, extreme.

My mother had been radiant in her richly embroidered dresses and saris. I loved her passionately. When my younger sister Kate was born, I was so traumatised by being displaced in my mother’s affections that I resolved to die.

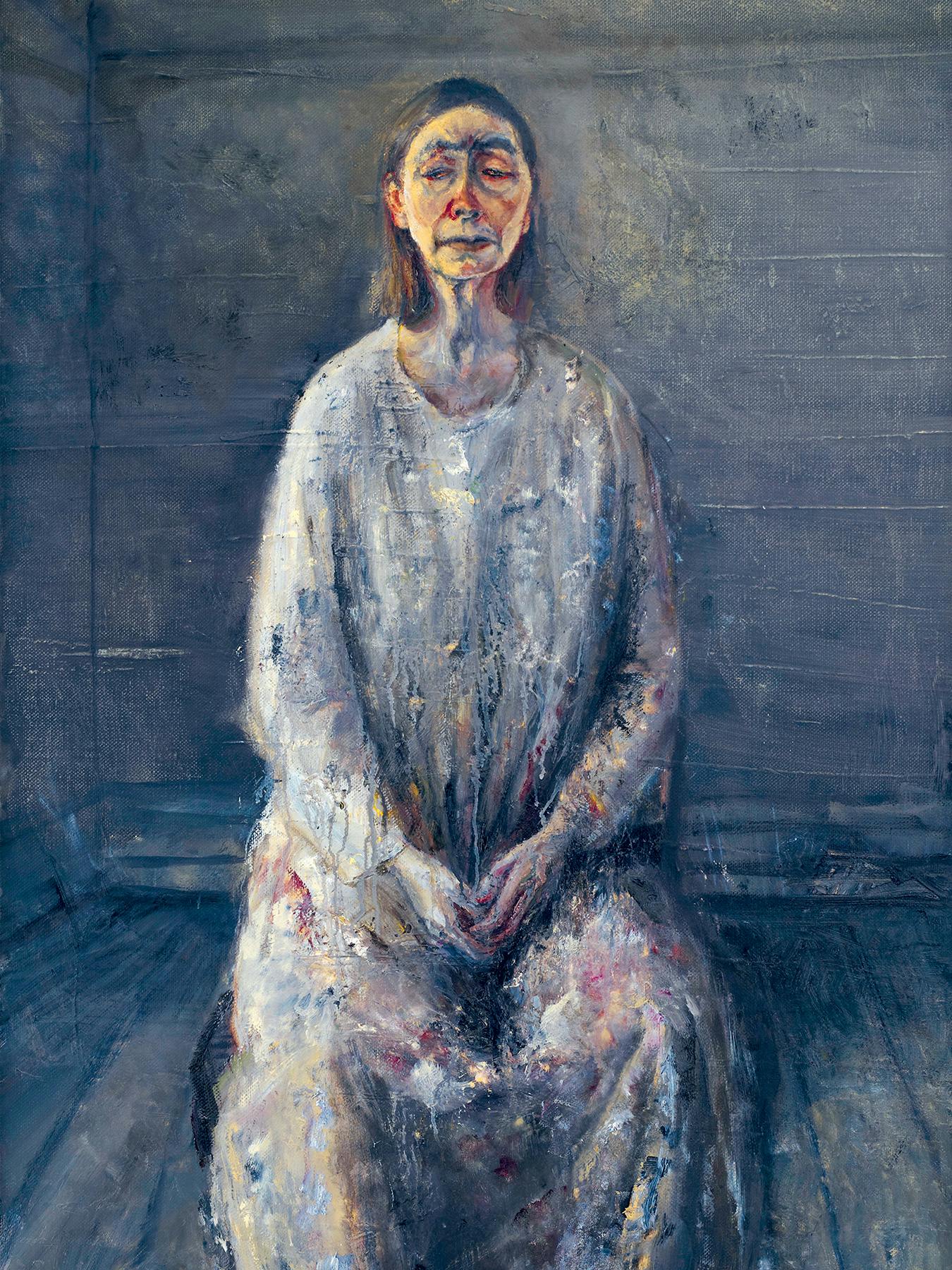

Self-Portrait’s direct language doesn’t quite convey the intensity of the author’s feeling—those screaming Indian villagers, a mother so loved that the arrival of a sibling would make Paul want to die. There’s something similar in Paul’s paintings, which can appear placid and understated but upon closer study yield fervent emotion.

Paul’s mother was one of the painter’s most rewarding subjects. Several of the portraits of her appear in this volume, and even in reproduction you can read the affection in the 2005 oil My Mother. An elderly woman in a diaphanous dress, she is thinner than in a portrait made 15 years earlier: not wasted, but sainted, with her beatific smile, her feet that seem not to touch the floor. She’s seated, and only the modulation of light and color imply a physical space behind her; she’s in the studio, or she’s in the kingdom of heaven. When Freud looked at Paul, she felt reduced; when Paul looks at her subjects, they are exalted.

Self-Portrait is loosely organized by theme, in chapters titled “Lucian,” “Home,” “Being a Mother,” “My Mother.” From them, the reader can piece together the particulars of Paul’s life: a happy upbringing with her four sisters, an adolescent mania for art that carried her to the Slade School of Fine Art, where she met Freud. The two had a son, Frank, in 1984, and their romance ended in 1988. Freud died in 2011. In a recent documentary, an art historian referred to him in plain hyperbole as “one of the great European painters of the last 500 years.” Self-Portrait illuminates what Freud’s long shadow obscured: Celia Paul herself, and an altogether different way of being an artist.

Though there are appreciable differences in their styles, as artists, both Freud and Paul are interested in people, depicted in constructed vignettes that imply some elusive narrative, a drama of the self. Generally, in these pages, Paul speaks of Freud not as a teacher, but a lover, a man who both delighted and frustrated her. She does not engage in the question of what effect his style might have had on her artistic development, nor does she answer whether her youthful experience modeling for Freud informed her own practice of painting from life—particularly her mother, her sisters, and her son, Frank—but a comparison suggests itself.

I have noticed that the men I have worked from are interested in the process of painting and in the act of sitting. The silence, when I am working from men, is less interior. Women, in my experience, find it easier to sit still and think their own thoughts, and they often hardly seem to be aware that I’m there in the same room. For this reason, I usually feel more peaceful when I’m working from a woman, and more free.

In My Sisters in Mourning, reproduced in this book, Paul paints her four sisters in shapeless white frocks, seated close together. They are arrayed by age, faces similar, as biological siblings’ so often are; it’s almost the progression of a single person over the years. The sitters’ hands are folded, almost in gestures of prayer. Paul speaks of the silence of her subjects in the moments she is painting them, and that quality exists in the finished work, too: the process informing the product.

This exchange between artist and subject, inside the studio, is clearly important. It’s not merely an act of looking—“If I know my subject well, it’s almost as if I don’t need to look at them in order to give them intense attention,” Paul writes—but one nearer collaboration. For Paul, the model is an active presence. She notes that for some early paintings she let her sister Kate read a book while she modeled; the finished work is a failure, “the vital spark is missing.” For Paul, the peculiar dynamic between artist and model is almost a moral question. As a younger artist, she painted her mother:

I peremptorily instructed my mother about what position she should assume: she should lie on her back and raise one leg slightly. When she faltered and didn’t get the position just as I had wanted, I shouted at her. I was very cruel. She cried and said that I was treating her like an object. I responded irritably to her tears and said that she didn’t believe in me.

She says her best student life drawings were of a model who wept, echoing the artist’s mother’s feeling of being dehumanized.

I empathised with her because I had so often cried when I sat for Lucian, and I understood how an awareness of how exposed one is, when lying naked in front of someone, can undermine one’s confidence, if one is made to feel undesirable.

Recall Linda, Paul’s adolescent artistic nemesis. In young adulthood, the two rekindled their friendship, and Linda became one of Paul’s subjects. An understated pastel of her, hands demure on her lap, eyes downcast, contains the same silence I divine in so many of Paul’s portraits. It’s a humane picture of a human being, with dignity and beauty and mystery. It is distinct from Freud’s glorious nudes because Paul is a different artist, yes. But it’s also a different approach altogether to the complicated matter of transubstantiating a real person into a work of art: the model as subject, not object.

If you want to know about Lucian Freud, William Feaver’s biography will be a better guide. He’s present in Self-Portrait, but he’s not very interesting. Paul recalls a double date: her and Freud, the painter Frank Auerbach and his never-named companion. It’s difficult not to cringe: “The woman doesn’t say a word and nor do I. We do not say a word to each other, either. Two dynamic scintillating men and two silent bewildered and embarrassed women sitting eating olives.”

Given time, Paul would assert a dynamic, scintillating personhood all her own. If Paul is correcting the record here, it’s to engage with the perception that she must have been the older artist’s muse at best or victim at worst. Freud had an unorthodox personal life, the father to 14 children by six women, but he and Paul were happy enough for the decade of their entanglement. That she writes of him with neither fondness nor exasperation isn’t a consequence of the author’s attempt at objectivity. It’s because he’s not the point.

There are moments, indeed, when it’s clear that Paul was not so much a muse as an influence—a far more active thing—on Freud. A teacher at Slade deemed her study of her parents and her sister Kate, Family Group, 1980, completed when she was 21, “a great painting,” and “Lucian admired it, too.”

In the weeks after seeing it, he often seemed preoccupied. He said, “I’m thinking of your painting.” He started to think about doing a big painting involving several sitters, and he ordered his biggest canvas yet to be stretched.

That would become Interior W11 (After Watteau). It’s a startling painting, five figures huddled together in a shabby interior. Paul modeled for it, alongside Bella, one of Freud’s two daughters with Bernardine Coverley, and Suzy Boyt, herself once a student at Slade, where she met Freud, by whom she had four children. Kai, Boyt’s son and Freud’s stepson, also appears in the composition, as does a young girl unrelated to the rest of this blended family. Though the title credits the eighteenth-century French painter, Paul wants us to recognize her role in this work’s genesis.

We cannot understand Paul as Freud’s prey, as we often do when an older, established person takes up with a younger, vulnerable one; they had a long relationship, not a brief affair. Infidelities and complexities aside, theirs was a union of mutual respect, and Paul makes it clear that their son is one of the great joys of her life. I liked the fact that the flat in which Paul continues to work—captured here in Room and Ghost of the British Museum—was a gift from Freud; if he gave her nothing else, he gave her this liberty, her own space. Freud’s final depiction of Paul, Painter and Model, shows Paul in spattered garb, brush in hand, tube of pigment beneath her feet. “I felt honored that Lucian should represent me in the powerful position of the artist.” He saw her as she truly was; what is that but love?

Celia Paul is a more gifted writer than she has any business being; it’s almost unfair. She joins the ranks of Anne Truitt, the great minimalist sculptor who wrote meditatively of her development as an artist, and Sally Mann, whose memoir Hold Still is a beautiful document of her life. By contrast with those artists’ memoirs, though, Self-Portrait reads like a novel. Paul alights on a topic, offers asides and digressions, circles back to her main point. The work is written with intention but wears it lightly.

Paul paints people she knows. You can read that intimacy in the work, or perhaps once you hear her explain this, you see the paintings anew. Her painting is not an act of close observation—she’s seen these people before—but some deeper communion with the person she’s aiming to fix on canvas. It’s impressive that she’s able to render them in words, too, on the page: Freud, her parents, and, of course, herself. You hear it in the book’s title: She’s no longer a naked girl with an egg—she’s granted that girl a self.