In a good short story, nothing happens until something happens, and makes you realize that actually something was happening all along. Without knowing it, this whole time you had been watching events already in motion unfold, seemingly random actions all hitched together and barreling toward a cliff. Lucia Berlin’s stories often start out soothing and small. They set beautiful scenes, catching the minor details of seemingly mundane moments and locations. They often concern people most of us might ignore—domestic workers, aging women, teenagers, drunks—who seem to be doing very little of import, and then they blow open to reveal the enormous interiors of the lives they depict.

Berlin is a master of this particular reversal, the sleight-of-hand aspect of the short story that puts the reader into the same unguarded state in which we find ourselves when our own lives’ losses come at us fast out of our blind spots. Her work is concerned with repetitive daily rituals, unremarkable lives, low-paying jobs, backwater towns, and unglamorous rooms. Even in those of her stories that take place against grander backdrops—the cast of Night of The Iguana taking over a hotel in Puerto Vallarta, the high society whirl of pre-revolutionary Chile—she focuses on the out-of-place details, the scratches on the picture, the ugliness that lurks at the margins, just beyond the edge of the spotlight.

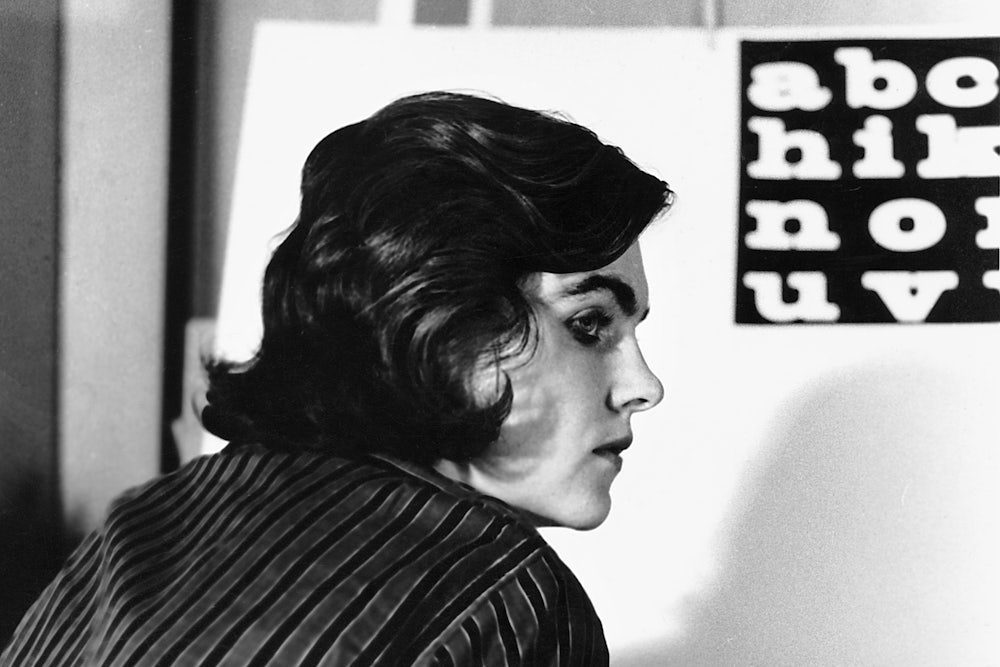

Berlin herself occupied this position time and time again in her own life, as someone who was continually proximal to more famous writers and artists, and, in her three marriages, to a certain type of grand genius man. In her friendships and correspondences, with better-known luminaries such as Robert Creeley and Denise Levertov, she was the figure outside the light, watching from the edges. A Manual for Cleaning Women, the blazing collection of her short stories published in 2015, eleven years after Berlin’s death, finally brought her literary prominence and a wide, admiring readership. But in her own lifetime, Berlin never enjoyed the same renown as so many of her associates did.

The term autofiction was coined in 1977 by Serge Doubrovsky to describe autobiographical writing by un-famous writers. Doubrovsky felt that autobiography was only the correct term for work by “the important people of this world,” whose recollected lives might be read as inspiring or instructional. Memoiristic writing by ordinary, unimportant people should be read in the same way as fiction: as descriptive, not instructive, with no greater meaning.

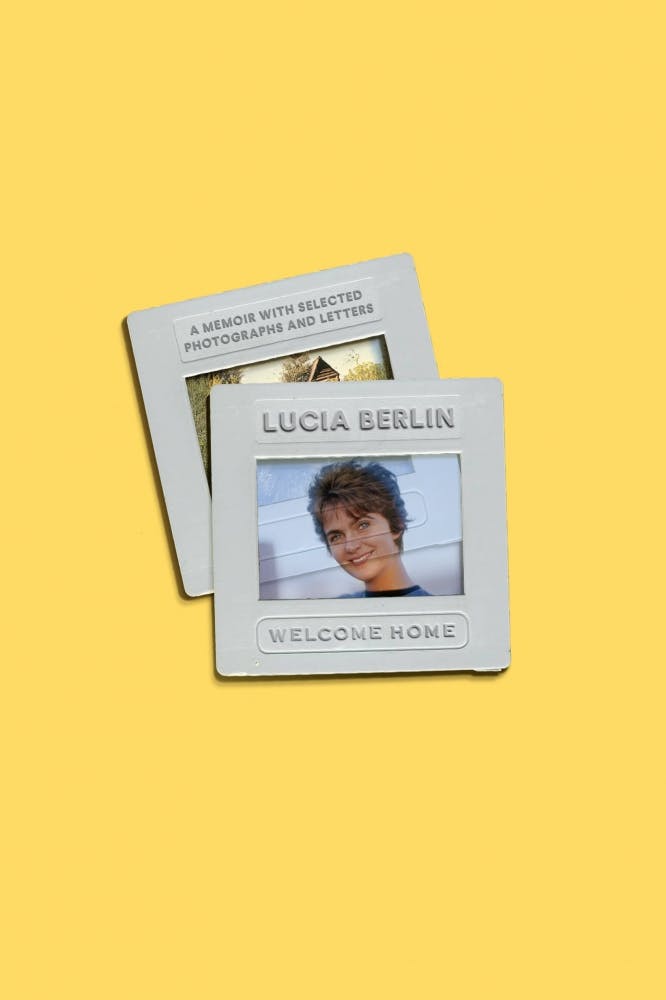

This definition of the term marks Berlin’s work as squarely autofictional. But her two new, posthumously published books also make it hard to find the line between autobiography and fiction, between a journal and a story, an anecdote and an event crafted into literature. Evening in Paradise is a selection of stories from the remaining, uncompiled pieces of Berlin’s as-yet unpublished work, continuing the revival project started in A Manual for Cleaning Women, and reintroducing many of the same themes and even characters. Welcome Home, however, is directly concerned with the character of Berlin herself. It comprises mainly the unfinished memoir she had been working on at the time of her death, fleshed out with photos and letters from her personal correspondence, provided and assembled by her son Jeff. The two books twine together, forming out of fragments an astonishingly coherent project of recollection.

It is tempting to read an artist’s work through the events of their life, or to read an artist’s life with the goal of locating the themes of their work, to assume that one offers the clues to the meaning of the other. But Berlin seems to take this approach to the material of her own life, hunting through it like a detective turning over a few pieces of evidence again and again. The stories in Evening In Paradise are the same story, over and over. The same choices and tragedies play out again and again—a very young woman marries a soon-to-be-famous sculptor, who leaves her while she is pregnant with their second child; a not-quite-as-young woman marries a rich, dashing man who turns out to be addicted to heroin; a couple in New Mexico struggle through the first year of their marriage on a property without electricity or running water; a young woman with several children cheats on her good, kind husband; the teenage daughter of an American mining engineer occupies high society in Chile and does her best to blithely ignore the imminent revolution.

People have sex, they drink too much, they lose their money, they take jobs cleaning and teaching and tending bar and selling drugs to scrape by. People die, and leave, and miss each other. These same events occur and reoccur; the same stories are told in first person, then in third person, from the point of view of the future, and from that of the past, in immediacy and in regretful retelling. The names change, the personalities shift slightly. Characters transform depending on agenda of the narrator. The more one reads of Berlin’s work, the more one begins to recognize the common threads, until every telling feels like a retelling, revealing a new facet of the same events, broadening and fleshing out the context.

These repeated stories are roughly a transcript of Berlin’s life. Born in Alaska in 1936, she moved first to Montana, Idaho, and Texas with her family. In her teens, her father’s mining business took the family to Chile, where she found herself part of wealthy pre-revolutionary high society. She returned to the States, to New Mexico, to attend college, and at age nineteen married Paul Suttman, a sculptor, who left her while she was pregnant with his second child. She married again twice, first to Race Newton, a jazz musician, with whom she moved to New York City, and through whom she was introduced into a group of musicians, artists, and writers that included Robert Creeley and Allen Ginsberg, and then to Buddy Berlin, with whom she lived in Albuquerque and Puerto Vallarta. Berlin’s heroin addiction dominated and eventually destroyed their marriage. Berlin moved to Berkeley, California and worked numerous jobs including as a cleaning woman, while battling alcoholism, and writing sporadically. In the 1990s, finally sober, free of both booze and husbands, she taught writing at the University of Colorado at Boulder, and then spent the last few years of her life in Southern California, near her sons.

By the time one gets to Welcome Home, these events are familiar, and only their presentation is new; it is like seeing the blueprints for a house one has already walked around in, whose decorated rooms one has already visited. We all know people—or are people—who tell the same story about themselves over and over. These stories, the ones that act as calling cards and life rafts, often gain inconsistencies through their repeated retellings. We navigate through our lives by preparing a polished and curated version of our own autobiography, with pieces we have learned to recite as a way of acceptably explaining ourselves to the people we meet. We carry around our own plot summaries and footnotes. The more we tell these stories, the more they become fictional—the act of telling taking over for the experience itself until only the former really exists.

The project of Berlin’s work, taken all together, is not one of pitting autobiography and fiction against each other, or even seeking the meaningful delineation between the two. It makes both autobiography and fiction part of the same attempt to gather up our experiences into something we can hold, carry with us, and offer to others—how we shape the things that have happened to us into a coherent self.

Throughout her life, Berlin struggled with alcoholism. In her work, she tells the story of this struggle at a distance, and at various removes, split into pieces so that the focus changes with each telling, yet all add up to the same idea. She writes about her mother’s alcoholism, about her former husband’s heroin addiction, and finally about her own drinking almost always in the third person, in stories where she blurs her identity out from the center by establishing a different first person narrator, as though squinting at something too painful to witness fully. Alcoholism is, among other things, a disease concerned with memory, a loss or obscuring of past events, whole nights and days pulled up by the root and weeded away. Her repeated tellings chart an attempt to make recollection cohere from incoherent pieces. Alcoholism makes memory more urgent by splintering it apart, placing it always just out of reach like a glimmering prize.

The stories in Evening in Paradise range in style and genre, as though Berlin is picking up and putting down other authors’ voices and approaches. A story about a young woman’s visit to the grand country home of a wealthy Chilean landowner is told in the style of Chekhov’s short stories or one of Turgenev’s novellas, right down to the characters reading First Love aloud to one another, while the story about the cast of The Night of The Iguana in Puerto Vallarta has the same lurid, gossipy, tragic sheen of Tennessee Williams’s plays. More than demonstrating the sensitivity of her ear, however, this mimicry also seems like another part of the same attempt to reconstitute memory from fragments, to achieve a somehow objective version of past events by gathering up and collaging all the potential versions alongside one another.

In women, any kind of autobiographical writing is often seen as amateurism. The descriptors memoir and confessionalism loom over women’s writing even when we are not writing about ourselves. The assumption is that women’s work is autobiographical, and that autobiographical work is confessional, messy, and selfish, an undifferentiated spilling of guts. But autobiographical work is also a documentary work, and the work of collecting, the slow accumulation of evidence. In Berlin’s repetitive, obsessive circling of the same events, told almost-but-not-quite true to life, ideas arise organically, and more persuasively, from quiet, repeated depictions of small and seemingly unimportant events.

In Evening in Paradise in particular, one thread that runs quietly but insistently through the book is women doing domestic work while men make art. Women clean houses and make dinners and tend to babies while men drink and talk and make grand pronouncements. Berlin neither dwells on nor complains about this, but merely presents it again and again until it becomes difficult to ignore. As in much of her work, the idea that there is some injustice here, that someone has been done wrong, that something in this world is off-kilter, is never presented through argument, but only through repetition.

The stories that use details and recollection from her teen years in pre-revolutionary Chile are similar. They are told almost exclusively from the perspective of the privileged class in which she dwelled as an adolescent, and they never belabor the theme of exploitation or wealth inequality. The same thing is true of those that depict addiction, or poverty, that depict the small, glancing slights of class difference, of the places where some people can go and others cannot. The stories merely portray the same circumstances, again and again, from slightly different angles each time, until a conclusion becomes unavoidable. Nothing happens, until something happens. Nothing seems very important until it becomes clear that, gathered up together, we have been watching something urgent, and much larger than it first appeared, unfold.