There’s a certain set of words associated with fiction by working-class writers. Their work is “gritty,” or it’s “grim.” Critics like to note the “darkness” of such fiction, then laud its “quiet dignity.” Characters might suffer, but they always patiently “endure.” So what should we make of Lucia Berlin, an unruly writer who set her short stories in the working-class communities of the American West, and who wrote about the lives of those who reside there with a stirring combination of horror and humor? “He reached over above me for the bottle,” she writes in one story:

drank, then took a different tool from the tray. He began to pull the rest of his bottom teeth without a mirror. The sound was the sound of roots being ripped out, like trees being torn from the winter ground. Blood dripped onto the tray, plop, plop, onto the metal where I sat.

This fiction isn’t quiet or composed; there’s plenty of pain, but there’s rarely pathos. Berlin’s tales of addiction and violence, formally unpredictable and drolly grotesque, defy our expectations for working-class fiction.

Her fictional world is populated by characters such as an Apache chief named Tony, who wears faded Levi’s and curses out housewives in laundromats; a Communist organizer, who attempts to recruit the daughters of expats in Chile; “El Tim,” an eighth-grade miscreant with extraordinary charisma, who manages to disrupt a Spanish class with well-timed whispers and a half-unbuttoned shirt; and Bella Lyn, the “prettiest girl in West Texas,” who blows smoke like a “petulant dragon” and tries to seduce men with what she calls her “sex appeal.” Berlin wrote about nurses and nuns, children of miners and teenage mothers, deep-sea divers and drug traffickers.

The most compelling character, though, is Berlin herself; her alter ego narrates most of her stories. This woman is an inconstant character, changing jobs and social positions with every move to a new city. In Chile, she’s the glamorous American girl who has her first cigarette lit by a prince. In Oakland, she’s an impoverished single mother; in New Mexico, she’s a graduate student, a substitute teacher, and solidly middle-class. She’s one thing, and then a moment later another.

If you aren’t familiar with Berlin, now’s the time to get acquainted. Born in 1936, she was the author of six collections of short fiction and from the mid-'90s on, a beloved teacher of creative writing at the University of Colorado. She was also, over the course of her life: a cleaning woman, a physician’s assistant, a high-school teacher, and a hospital ward clerk. Married and divorced three times, she raised four sons while battling the alcohol dependency that plagued three generations of her family. She moved frequently, first as a child and then as an adult; her itinerant life took her from Alaska to Santiago to Albuquerque to the East Bay. She died in 2004, just a few years after her fiction began to gain wider recognition.

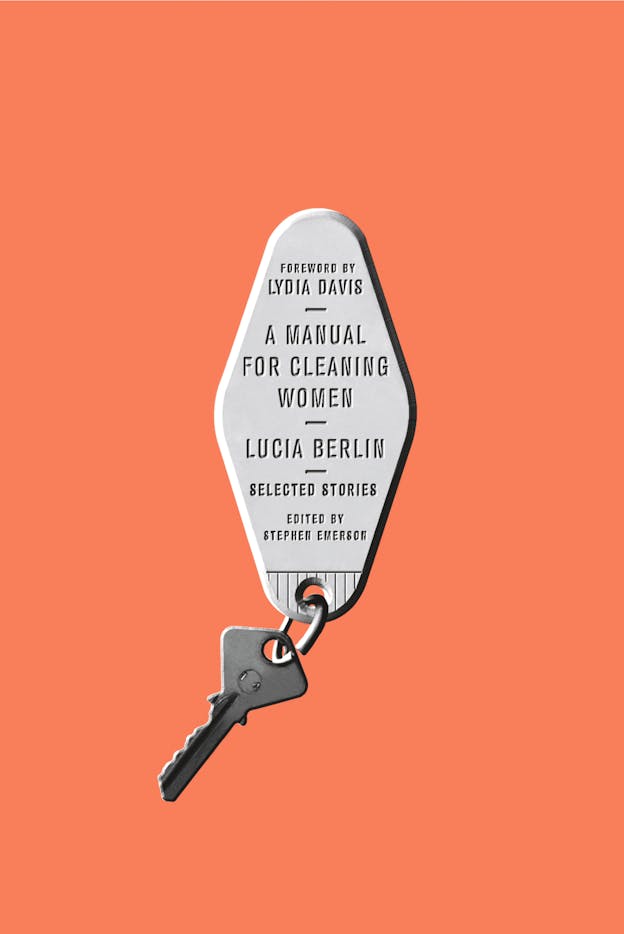

With a foreword by Lydia Davis, A Manual for Cleaning Women brings together 43 of the unconventional, unnerving stories Berlin wrote over the course of thirty years. She published her first story in the Atlantic Monthly in 1960, when she was 24, and her last with Black Sparrow Press, the publisher of three of her collections, when she was 63. For years, Berlin was a favorite of writers like Davis, Ed Dorn, and Paul Metcalf, who declared her “a challenge to… the East Coast mind.” Published by small literary presses throughout her career, her reputation didn’t extend much beyond the West coast, though she gained pinpricks of attention elsewhere. August Kleinzahler reviewed Where I Live Now for the London Review of Books in 2000, and when she died, the magazine published excerpts from her letters to Kleinzahler, vivid, intriguing fragments of a life. “Blizzard in NY, no cars!” she reports in one of the letters. “Walked, pulling kids on a sled, to Moma for a Rothko retrospective. Few people, the light from the skylights dazzling, his colours pulsated from the walls, pure, as, well, Arkansas roads.”

Some of her stories, such as “My Jockey”—five paragraphs that won the Jack London Short Prize in 1985—are brief snapshots. This particular story freezes the chaos of an emergency room just long enough to show how gorgeous an injured body can be. Others, like “Mijito” (1998), in which a Mexican immigrant tries and fails to care for her ill child, meander across several weeks and points of view, in order to describe the lives of multiple people. Yet her stories are remarkably consistent in theme and setting. Most are set along the western coast of the Americas, and many present the struggles of damaged individuals and dysfunctional families. A few characters crop up repeatedly—an alcoholic mother, a dying sister, a lecherous grandfather—though they appear in new guises and are differently named. She frequently uses flashbacks, and she’s a fan of the catalog (“Smoke and chili and beer. Carnations and candles and kerosene”). Her writing is especially animated when it portrays illness or death.

In “Tiger Eyes,” a story set in a crowded abortion clinic, she describes one patient’s bad turn.

Blood was everywhere. She was hemorrhaging badly, tangled up in coils and coils of tubing like a berserk Laocoön. The tubing had clots of bloody matter sticking to it. It arched and buckled, slithering around her as if it were alive.

Such violent episodes recur throughout Berlin’s work, in her later years becoming more evidently crafted. The stories she wrote while working as a writing teacher hew more closely to the workshop model many twenty-first century readers will recognize. “Here It Is Saturday,” 1996 story about a prison writing workshop, follows the familiar prescription for good short fiction—keep the drama offstage, and end with a gut-punch of a final sentence.

Berlin used short fiction, however, to offer unusually detailed portraits of working-class lives. Often, she presents readers with specialized knowledge she’s picked up from working her menial jobs. In the collection’s title story, for instance, she tells you what cleaning women won’t steal (jewelry) and what they will (sesame seeds). They don’t want gifts but they will accept them, only to abandon them on the city bus, as they voyage on to the next job. From “Unmanageable,” (1992) you learn that Oakland liquor stores open at 6am, that a half pint of vodka costs four dollars, and that it will take ninety minutes to walk from Berkeley to Oakland and back again, which is just enough time to drink the vodka, shower, and make breakfast for your sons. It’s a chilling story, but its tone is almost victorious. When the protagonist arrives home, she cries, not with sadness or shame with “relief that she had not died.”

Neither self-pitying nor stoic, this attitude toward suffering, both one’s own and others, emerges in many of the collection’s most memorable stories. In “Dr. H. A. Moynihan,” (1981), a dentist enlists his young granddaughter in the pulling of his own teeth. She sterilizes tools and holds a mirror as he tugs and swills whiskey and vomits and bleeds. He pulls every tooth, then passes out, teabags nestled in the places where his molars used to be. The image is amusingly ghoulish—he is, the granddaughter observes, like “a teapot come alive.”

To be sure, she could be grotesque. “Strays,” her 1988 story set in a methadone clinic outside of Albuquerque, tells of two patients engaged in a nighttime tryst, when their coupling is interrupted by a pack of stray dogs. “They had gotten into porcupines,” Berlin writes. “Must have been days ago because they were all so infected, septic. Their faces swollen like monster rhinoceros, oozing green pus. Their eyes were bloated shut, quilled shut with tiny arrows.” The strays become the barely-living embodiment of the pain suffered by the clinic patients. The man takes pity on the dogs and beats them to death with a sledgehammer.

Berlin lived among America’s working class and poor, and she wrote about them again and again. Had she published more widely in the 1970s and 1980s, it’s likely that she would have been compared to Raymond Carver and lumped in with the rest of the minimalists. But though Berlin admired Carver, and though she shares some subject matter with his descendants, her prose is far from the simple, spare writing that characterized minimalist short fiction. In a passage Carver never would have written, she riffs on a hospital patient’s eyes: “Little beady black eyes laughing from epicanthic gray-white folds. Eyes just past Buddha eyes … sloe eyes, slow eyes, near-Mongoloid eyes. Kentshereve’s eyes, laughing into mine.” Allusive and lyrical, her writing looks more modernist than minimalist.

Unlike Carver, Berlin didn’t generalize or ironize working-class experience; she instead presented her neighbors in all their compelling specificity. “I like my job in Emergency,” one of her characters says in a story called “Emergency Room Notebook, 1977.” “Blood, bones, tendons seem like affirmations to me. I am awed by the human body, by its endurance. Thank God—because it’ll be hours before X-Ray or Demerol. Maybe I’m morbid.”

There’s that celebration of the human spirit—the dignity and endurance we expect—but it’s soon undercut by self-recrimination, delivered tongue-in-cheek. The passage is a cross between an ars poetica and a self-defense. What this writing affirms is the beautiful, broken human body as well as Berlin’s rightful place in the canon of American short fiction.