In 1972, Carol Merrill, a graduate student at the University of New Mexico in her early twenties, sent a letter to Georgia O’Keeffe at the artist’s adobe house in Abiquiú. O’Keeffe was 85 years old and an international celebrity. She had been showing her paintings for over five decades, and due to macular degeneration, had set aside her oil paints to begin a series of abstractions in watercolor. Merrill’s letter was short and to the point. “Dear Georgia O’Keeffe,” she wrote. “I want to meet you. I do not want to intrude on your privacy—your solitude. I would like to see you, be near you for just a few moments and learn if I have the strength and power to proceed in my work by witnessing your will.” Merrill, who worked at the university library, enclosed a photograph of herself sitting in front of a typewriter.

O’Keeffe received dozens of such letters each month, often accompanied by trinkets her admirers thought she would appreciate: smooth stones, snippets of poetry, snapshots of landscapes. She had no reason to reply to Merrill’s note in particular. But it just happened to land in the hands of her secretary on the right day, at the right time, and that was that. According to biographer Nancy Hopkins Reily, “The brevity and simplicity of Carol’s letter attracted Georgia’s attention and she must have recognized a nonconformist thinking.... In a rare gesture Georgia invited Carol to visit her on a Sunday but to stay for only one hour.”

Merrill did not respond to the invitation for six months. What do you do when one of your heroes responds from the void? Merrill kept the reply folded up in her backpack, like a gremlin she was trying to prevent from escaping. But it kept glowing from whatever pocket she put it in: Answer me, answer me. When Merrill finally told an artist friend about it over spaghetti, she recounted, he “scolded me strongly and admonished me to write an answer or call her immediately.” He said that O’Keeffe never did this, that she had received the rarest of opportunities, that she was blowing it.

Merrill made the one-hour appointment for an August morning. She and O’Keeffe sat in the artist’s sitting room, with its giant, raw, wooden ceiling beams and big picture window that looked out onto lilies, stones, and salt cedar trees, and discussed health food. Long before it was in vogue, O’Keeffe was juicing daily and sourcing hearty, minimalist soups from her garden, and sending a local man on a 90-minute hunt to procure farm-fresh milk every other day. Though her eyes were going, O’Keeffe was determined to keep her body strong. She lived to be 98, and was able to speak in lucid terms about her work almost until the day she died, in March 1986.

Merrill’s hour-long visit turned into a part-time job; she became O’Keeffe’s in-house librarian, organizing the artist’s rare books—a first edition of Ulysses, obscure volumes of E.E. Cummings—in a chilly yellow room off the house’s main courtyard. Her role eventually expanded to cook, secretary, and companion. She read to Georgia from her favorite books, including biographies and the Taoist text The Secret of the Golden Flower. They drank orange blossom tea together. Merrill also kept O’Keeffe’s secrets: For the sake of the art market, no one could know that the artist was going blind. They walked together, a lot. The New Mexico desert is made for extended meandering; it’s never humid, and it is easy to find a comfortable pace on the soft sand of the foothills. When she thinks of O’Keeffe, Merrill recounts in her memoir, she likes to think of her “walking in beauty beneath the ancient cliffs at Ghost Ranch.”

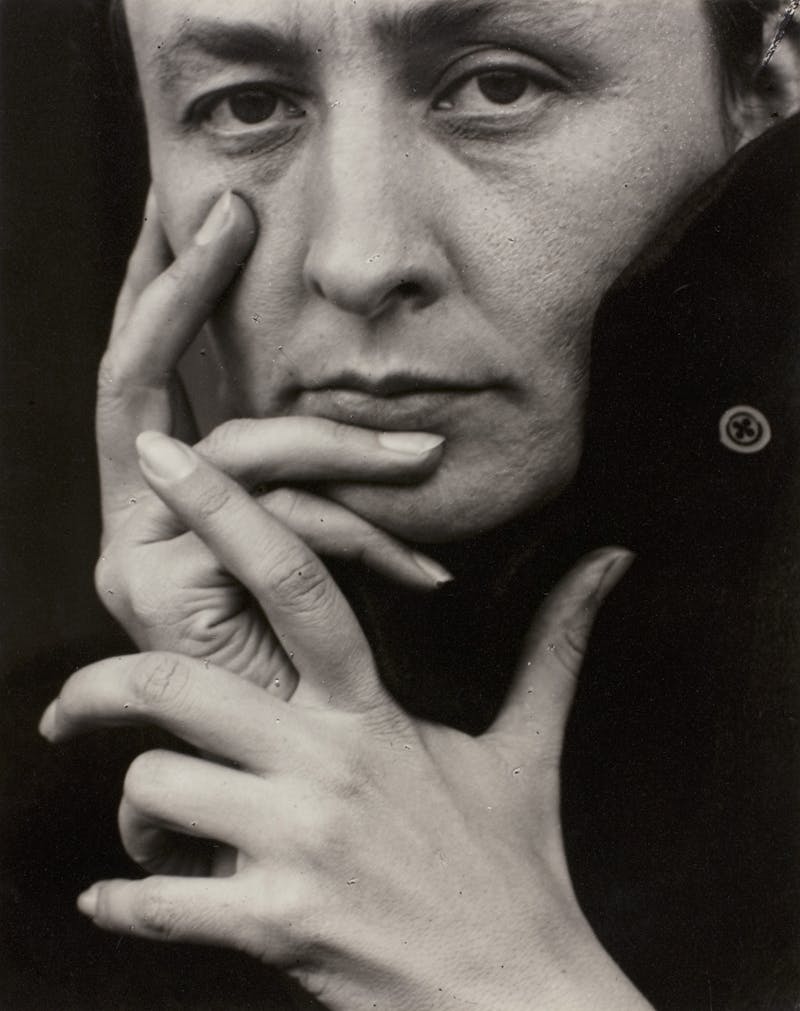

I found myself thinking a lot about Merrill recently, when I walked through “Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern,” the new blockbuster exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. The show, curated by modernist scholar Wanda Corn, will live in Brooklyn through July before hitting the road for a nationwide tour; the demand has been so great that the museum is issuing timed tickets for the exhibition to manage the crowds. “Living Modern” is not so much a show about O’Keeffe’s art as it is about her mythological, heroic image—the undefinable “will” that fascinated and inspired admirers like Merrill. The show is primarily about how others viewed O’Keeffe: It includes her clothes, personal artifacts like her collection of mother-of-pearl buttons, and nearly 100 photographs of her, from those taken by her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, to a Polaroid shot by Andy Warhol in 1980. But the exhibit is also about O’Keeffe’s role in these images—how she styled and accessorized her own legend.

I am not of the opinion—posited by some critics in response to this show—that clothing is a distorting lens through which to view an artist’s life work, especially in the case of O’Keeffe, who extended her powers of creativity to her self-presentation. I can, however, see the logic in the argument that an exhibition like this one is essentially gendered: Of course we would want to see a woman’s clothes; of course that’s what unlocks the key to who she is. Writing in the New Republic in 1925, the critic Edmund Wilson praised O’Keeffe’s work, but also seemed intent to reduce her genius to her personal style. He wrote: “Where men’s minds may have a freer range and their works of art be thrown out further from themselves, women artists have a way of appearing to wear their most brilliant productions—however objective in form—like those other artistic expressions, their clothes.”

It’s hard to imagine, say, a show made up entirely of Marcel Duchamp’s long black neckties and overcoats doing as well as “Living Modern,” or at least that anyone would accuse him of wearing his work like an outfit. But O’Keeffe’s playful engagement with her own image is worth exploring, even if she would have rejected the impulse to define or limit herself by it. She wore pink wrap dresses and raw denim dungarees; both served a practical, daily function in her desert life. To an outside observer, it may have seemed as if she were winking at traditional femininity. But while she consistently skirted labeling herself as a feminist artist (even though she was the only living artist to have a place set for her in Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party), she refused to be demoted because of her gender. In her first show in 1917, where she was the only woman on display, she rejected any attempt to separate herself from “the boys,” as she always referred to male artists. At the same time, she wasn’t unaware of her beauty or how her striking physical aesthetic affected others. She knew what she looked like, in her impeccable wool suits, her flowing head scarves, her black Stetson hat, her enormous Calder brooch twisted into the letters “O” and “K.”

The bulk of the exhibit, and one of the reasons it has been so popular, is a collection of O’Keeffe’s clothes, many of which she sewed herself. The first room displays a selection of her loose cream silk tunics, which would not look out of place in an Eileen Fisher boutique. Moving through the show, viewers get to see O’Keeffe’s black woolen cloaks, her collection of sharp, tailored designer suits from Knize and Balenciaga, her button-down work shirts and blue jeans, her pastel cotton wrap dresses from Neiman Marcus (one comes in dusty millennial pink), a display case of her petite Ferragamo ballet flats in a variety of colors (when she found an item she liked, she repurchased it in many fabrics), and, in the second-to-last gallery, a selection from the 20 or so kimonos she favored later in life, when Merrill was reading to her from Taoist texts.

O’Keeffe acquired some of her kimonos in the United States in the 1910s, later bought them in Asia, and finally purchased a large number from a store called Origins in Santa Fe in the 1970s. She liked to tie them the “Western way,” overlapping the left side over the right. In the show catalog, Corn concedes that there is a “touristic” quality to O’Keeffe’s kimono obsession, and that she participated in the appropriative wave of “Japonisme that swept across the Western world at the turn of the twentieth century, popularizing kimonos among progressive artists, female college students, and any woman who gravitated to clothes that showcased her modernity.” Still, Corn writes, O’Keeffe primarily favored the garment because she felt it was simple, streamlined, and comfortable. She liked clean lines and muted colors, precise tailoring and careful pintucks, with an aesthetic that tilted toward minimalism and function.

Many photographers—including Cecil Beaton, Ansel Adams, Mary Nichols, Laura Gilpin, and Bruce Weber—shot O’Keeffe throughout her life. If “Living Modern” has a major thesis, it’s that Georgia loved to sit for the camera. The images are all so carefully composed, so architectural, so full of her returned gaze, that it is difficult not to feel her willpower guiding every frame. Although Stieglitz took several nudes of the young artist, the way she aggressively stares down the camera in these images suggests that she was less an object of his work and more a conspirator in it.

She knew how she wanted to be seen, and she sculpted her own fame. Her paintings made her wealthy and famous. She was the highest-paid woman artist in New York City within a decade of moving there from Texas. But her self-presentation—the high priestess of the high desert in crepe dresses and dirty work boots—made her an icon. She was a wisp of a woman making paintings that were often larger than herself, pulling hyper-saturated turquoises and fuchsias out of the dull earth. She put together the hardy and the delicate and the efflorescent in a way that no one had before, and just like that, the world shifted.

Notably absent from the show are O’Keeffe’s most popular paintings—the dilated, pillowy florals that critics insisted on reading as some sort of yonic symbology, despite her stern protestations that they were wrong. She always took more of a “made you look” approach to her decision to paint flowers: In 1939, the artist, who was never a woman of many words, decided at last to clarify the purpose of her giant blooms. “I made you take time to look at what I saw,” she wrote. “And when you took time to really notice my flowers you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don’t.”

“Living Modern” contains a scant number of paintings, glorious though they are (my favorite is Pelvis II from 1944, a close-up image of a cow bone gleaming stark white against the Taos sky, blue as a chlorinated pool). Like many modernists, O’Keeffe loved shapes most of all; the rigid and pliable edges of what can be seen. Her boxy blouses and fitted suits underpin her devotion to form as the wellspring of creativity; her body was a minimalist canvas, and she took the time to swaddle it in unexpected proportions. Her self-presentation skewed quieter, however, than the operatic flowers of her best-known artwork. Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 from 1932, for instance, has a touch of the baroque, all curling petals and almost Technicolor pigmentation. One senses that O’Keeffe kept her clothing simple so that she could infuse drama into her art. “Living Modern” encourages the viewer to make this calculation: She lived with few embellishments so that her art could be bold; she did not need accessories when she was capturing the walloping adornment of the land.

“Living Modern” feels like an extension of Merrill’s first swooning letter to the artist four decades ago. It is that yearning impulse to be in the artist’s presence, to be near “for just a few moments” to see if any of her strength might rub off by osmosis, that drives the exhibit—and, I would argue, a new generation of O’Keeffe fanaticism. (Between the touring exhibition and a hulking new cookbook of her favorite recipes, we are in the midst of a highly Instagrammed Georgia revival.) Nothing illuminates a person’s bodily presence like the body’s absence in clothing they once wore. Yes, O’Keeffe’s hands are all over her paintings, but her entire self lived in these garments; she sweated in them, walked in them through mud, cooked chicken enchiladas and green chiles with eggs. In a world where we feel less and less corporeal, living through screens and feeds, there is an urgent quality to encountering someone’s intimate, daily choices—what they wore, what they ate, what they smelled.

In 1995, Merrill published a volume of poems she wrote about O’Keeffe called O’Keeffe: Days in a Life, which you can purchase at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. I’ve had a battered copy for years—I am from Albuquerque, where visiting the museum is a regular, almost religious, practice—and my favorite poem from it is number 21, from 1974, which describes what O’Keeffe eats for breakfast. It ends:

...the bread a meal in itself whole wheat and soy flour,

wheat germ, ground flax seed,

sunflower seeds, and butter,

mixed with safflower,

then savory jam maybe

ginger and green tomato

or sweet raspberry.

One day she said

what do you write about me?

Are you going to tell

what I eat for breakfast?

O’Keeffe apparently gave her blessing to Merrill’s poetry (her glowing review was, “It will do,” according to Nancy Hopkins Reily), as did Allen Ginsburg, who read the manuscript and praised it as “sacramentalizing everyday life in a world of genius.”

In New Mexico, the O’Keeffe enchantment starts young; the quotidian world becomes sacred under the overwhelming sunsets and watermelon mountains and the constant smell of burning piñon and cedar in the air. With her choice to move West, she consecrated the land with her paintbrush, and her paintings became shorthand for understanding a state for those who have never been there. And yet O’Keeffe did not want to belong to New Mexico. She wanted her image spread wide. She courted celebrity even as she claimed to eschew it; she played hard to get so that people would keep coming around trying to find her. Because if they came to find her, they also encountered her work. They saw the twists in the river just the way she did, they saw the odd bend of a weather vane, they saw stamens blown up into architectural spectacle. O’Keeffe laughed at the idea that anyone would care what she ate for breakfast, yet she also understood that the mythology surrounding an artist’s practice was useful material. It keeps people looking, long after you’re dust.