In April 1917, as the final show at his gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue, Alfred Stieglitz mounted Georgia O’Keeffe’s first solo exhibition. A centennial is the sort of occasion curators can’t resist, and it should be the raison d’être of Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern (a show in which, fittingly, vexingly, Stieglitz looms large). But curators can’t resist self-congratulation either, and the Brooklyn Museum wants us to relate the show to its 1927 exhibition of the artist’s work. Fair enough. Anyway, O’Keeffe belongs to that very small pantheon: an artist whose work doesn’t need a reason to be revisited.

Living Modern is an exhibition the like of which I’ve never before encountered. It’s an assemblage of art, photography, and relics, principally clothes, and explores how one of the last century’s most gifted artists constructed one of the last century’s most enduring personas. A more accurate title might have been Georgia O’Keeffe: The Brand.

In her exhaustive biography of the artist, Roxana Robinson quotes O’Keeffe on one of her instructors at the Art Students League, William Merritt Chase: “He arrived for class in a silk hat, flower in his button-hole, fur-lined coat, very light gloves, spats, and a neat brown suit. When he entered the building a rustle seemed to flow from the ground floor to the top that ‘Chase has arrived!’” Robinson posits that the way in which Chase embodied the role of artist had an effect on his pupil; wherever she learned it, Living Modern documents how O’Keeffe made this role her own.

Clothes don’t make the man (I’m hard pressed to imagine the museumgoers of the future queuing up to see Schnabel’s sarongs) but clothes have an interesting role in the making of the woman, at least this particular woman. There’s something gutsy in Living Modern’s decision to show the artist’s wardrobe alongside roughly contemporaneous work. I don’t personally buy that the organic forms of O’Keeffe’s early watercolor abstractions are related to the dresses she favored. Still, it’s daring to relate the pintucks on a linen blouse (attributed to the artist herself) to the botanical detail in her 1928 painting 2 Yellow Leaves. Why not?

There’s every reason to be skeptical of an exhibition that includes the artist’s shoes, and it’s hard to imagine Living Modern being mounted 20 years ago. The whole notion just sounds so trivial, so material, so sexist, so utterly beside the point. But O’Keeffe is a confounding case. Just as she was maturing as an artist, she became entangled with Stieglitz, as lover and companion, yes, but also as subject. His photographs of beautiful young O’Keeffe were artistic exploration, and they were collaboration (she feels like the co-author of those photographs). But it’s impossible to ignore her beauty, her nudity, her exposure. The clothes on view here, designed or modified by the artist, are a riposte to the Stieglitz photos (too many of which end up in the show). They’re testament to the fact that Georgia O’Keeffe, Inc. wasn’t something Stieglitz dreamt up.

Maybe it’s impossible, age of mechanical reproduction and all, to really see the work of an artist like O’Keeffe. Her skulls and flowers are dorm room staples, and traditional retrospectives exist largely to reify that what you’re looking at is Art. You stand before a famous painting, feel that frisson of recognition, Instagram it, and move on. While it is in no way the intention of this show to be a retrospective, the works by O’Keeffe that are included are uniformly phenomenal and very smartly chosen. The fact that I wanted more of her work is my failure, not the exhibition’s. Nevertheless: A central gallery holds three blouses, four black garments, 16 photographs of O’Keeffe, and three of her paintings. The math felt off to me.

I love looking at clothes but was far more interested in Manhattan, a 1932 oil that began as a study for a MoMA mural commission. I love looking at fashion photography but was far more engaged by how the artist conveyed massive scale on a modest canvas—in East River No. 1, a 1926 view of the Manhattan skyline and in the 1946 landscape Part of the Cliff. I love looking at ephemera, but, apologies: The vitrine containing the artist’s cotton bandanas made me laugh.

Living Modern’s goal is to track how a girl born on a Wisconsin farm during the administration of Grover Cleveland became famous enough to be photographed by Andy Warhol. I accept wholly the show’s central premise, that she did so in part by deliberately fashioning a persona so alluring that we’re still talking about it. But a persona can be a prison, can’t it? The show is divided between the artist’s relationship to New York, then New Mexico, then Asia, but it closes with a section on Celebrity, the place to which O’Keeffe ventured, finally, and from which she may not be able to return. This very smart exhibition’s intent is to interrogate O’Keeffe as celebrity, but I suspect it will serve mostly to cement her status as such among a whole new generation.

In this final gallery, we see the artist’s Balenciaga suit and well-worn Ferragamos, a spread in Interview and the Warhol silkscreen, a Cecil Beaton portrait for Vogue, the adoring photographs by Philippe Halsman, Arnold Newman, John Loengard. In most, O’Keeffe is decidedly on-brand: the Bohemian babe all grown up, somewhere between shaman and an especially severe nun. I thought of Robert Mapplethorpe’s famous portrait of Louise Bourgeois cradling a stone phallus. That’s what happens, sometimes, when you age out of being a woman of a certain age: You end up as camp. It’s only Dan Budnik’s portrait of a smiling O’Keeffe, eleven years before her death, that offers a slightly different view of the woman: as someone bemused at having so long performed the role of herself.

In her biography, Robinson quotes O’Keefe in a 1922 letter:

I don’t like publicity—it embarrasses me—but as most people buy pictures more through their ears than their eyes—one must be written about and talked about or the people who buy through their ears think your work is no good—and wont [sic] buy and one must sell to live—so one must be written about and talked about whether one likes it or not—It always seems they say such stupid things.

O’Keeffe may well have felt embarrassed by publicity, but Living Modern reveals an artist who got over it (either that or one who would hate this show). It demonstrates how O’Keeffe used fashion and how fashion in turn used her; especially illuminating—or egregious—is a Calvin Klein ad that affixes the designer’s name over a Bruce Weber photograph of O’Keeffe’s New Mexico home. (Klein and Weber shot several photos there, with the designer modeling his own garments; the show’s wonderful catalog includes one and it is, frankly, hilarious.)

The viewer who takes umbrage at the presence of fashion inside our museums (does such a person still exist?) will not enjoy this show, though the curators impressively balance accessibility with intellectual rigor. It hardly matters; fashion in museums is catnip for crowds. Admission to Living Modern will be via special, time-specific tickets. The galleries will be crowded and the wall text hard to read; the audience will swoon over the 1954 Pucci dress and the Halsman portrait of the artist posed below a skull, and they’ll come away knowing the very O’Keeffe that she wanted us to know.

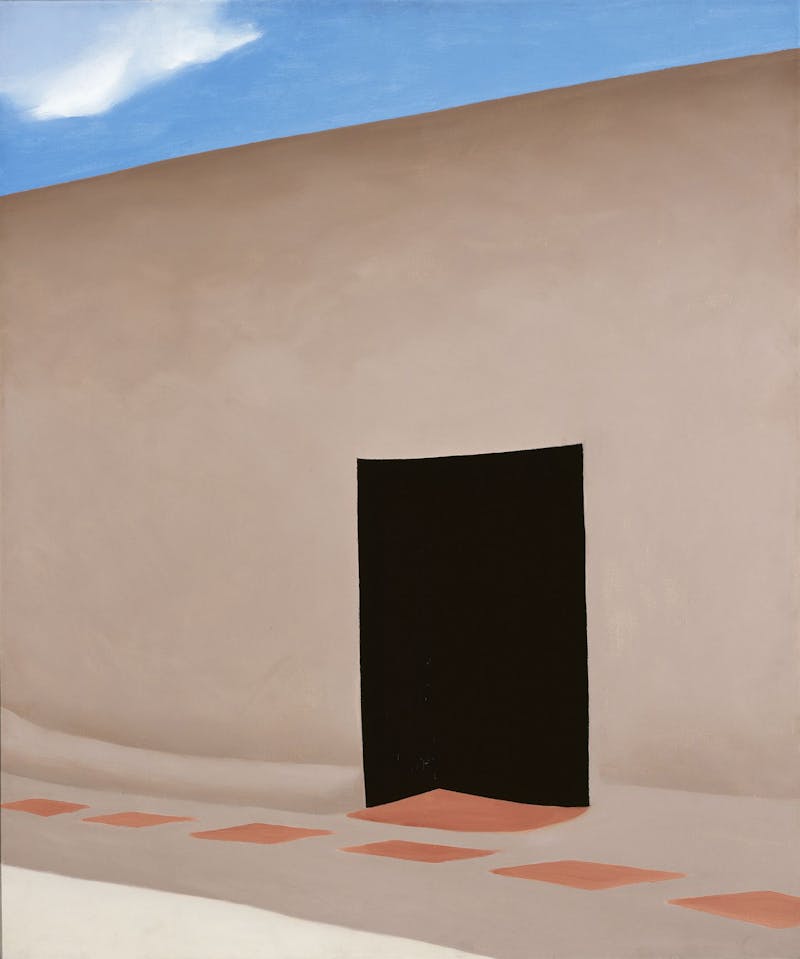

That said, the museum has included what I think are two of the greatest paintings I’ve ever seen in person: Pelvis II and Patio with Cloud. The shoes, the clothes, the photographs—they’re fascinating relics of a woman who attained secular sainthood, but they cannot but pale in comparison with O’Keeffe’s actual miracles.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to the exhibition as Making Modern. It is Living Modern. We regret the error.