Confessions of a Frequent Flier

Why is the airline industry so hard to decarbonize—and can we ever expect to fly guilt-free?

This year, I became an Airport Person—an awkward position to be in as a climate journalist. Before, I tried to limit my regular travel to buses and trains where possible. But over the winter, I started a relationship with someone who lives on the West Coast, and now I find myself haunting JFK Airport every few months on jaunts to go see her. (I even bought one of those dorky neck pillows—all in the name of love.)

It’s awkward because long-haul flights are among the most atmosphere-damaging actions you can take as an individual. A one-way flight from London to New York can generate more carbon dioxide per passenger than the average person in 56 different countries emits in a year.

All that time dragging my suitcase around terminals and crammed into impossibly tiny seats in economy class has given me a lot of opportunity to think about the ethical conundrum I’ve found myself in. Not all fliers are created equal: People who travel by plane regularly are responsible for an outsize chunk of global airline emissions. The various airlines I fly on, I’ve noticed, have offered me some small consolations for my climate betrayal, from promises about more efficient aircraft design to assurances that they’re using “eco-friendly” packaging for in-flight snacks.

The whole thing feels like one of those impossible modern climate catch-22s. Am I really supposed to choose between not destroying the planet and seeing my girlfriend? Why is this industry so hard to decarbonize? And how are we supposed to trust that airlines are actually doing what their green P.R. says they are?

I’m far from the only one asking these questions. Late last month, Delta got hit with a class-action lawsuit claiming that it erroneously represented its green credentials. The lawsuit states that plaintiff Mayanna Berrin, a California resident, was led to buy tickets thanks to the airline’s advertising claims around its carbon neutrality, “due to her belief that by flying Delta she engaged in more ecologically conscious air travel and participated in a global transition away from carbon emissions.”

Delta had made a bold pronouncement in early 2020. “Starting March 1, Delta Airlines will become the first airline to go fully carbon-neutral on a global basis,” CEO Ed Bastian told CNBC’s Squawk Box in an interview. As the lawsuit details, the airline followed this announcement with similar claims on social media and in advertising—including on in-flight napkins—which led Berrin to feel better about buying so many flights.

Carbon credits were a key part of Delta’s sustainability strategy at the time: paying for a project somewhere in the world that theoretically pulls carbon out of the atmosphere—like planting trees or restoring carbon sinks—to offset the emissions damage done by flying. Dan Rutherford, a program director at the International Council on Clean Transportation, told me that Delta’s tactic was a pretty standard move for the industry at the time. “The focus was very much on, OK, the aviation sector is very hard to change,” he said. “Let’s not worry about the planes themselves and the fuels they burn. Let’s offset their emissions.”

Unfortunately, buying offsets doesn’t wave a magic wand to make all the emissions from a major airline go away. We published a great piece last week illustrating problems with offsets, but the offset market is, in sum, rife with problems—and, in many cases, can enable polluters to release even more emissions into the atmosphere. These issues are a cornerstone of Berrin’s lawsuit, which claims that Delta led consumers into thinking it emitted no CO2 after March 2020, even as it was continuing to do (mostly) business as usual.

Regardless of the outcome of the lawsuit, sustainability claims may change substantially for the industry moving forward. Over the past year, Rutherford told me, airlines have shifted their carbon-reducing strategies away from offsets to focusing more on sustainable aviation fuels—an umbrella term for different types not derived from fossil fuels, including some made with biomass feedstocks. While they have much lower carbon emissions, these fuels tend to be very pricey, costing several times more on average than traditional ones—a nonstarter for an industry that operates on razor-thin margins and tries to squeeze every last penny out of customers.

As part of its massive package of climate investments, the Inflation Reduction Act added an additional tax credit on sustainable aviation fuels that, Rutherford said, airlines can stack on top of other existing incentives to get a steep discount.

“We’re throwing a lot of money … very randomly at fuels,” he said. “And we’re throwing a lot of money at some technologies that have already matured and we don’t expect the cost to come down much more. Which is not great public policy.”

Still, Rutherford said he thinks there’s potential for flying to change. The industry has set a benchmark of totally decarbonizing by 2050; Rutherford said that by 2035, a combination of sustainable fuels, developing technologies like hydrogen and lighter batteries, and increased customer tools, like more detailed breakdowns of emissions by itineraries, should get us to a point where we’ll know if we’re heading toward that goal or not. That’s way longer than I hope my girlfriend and I will be living on separate coasts but seems promising given the huge scope of the problem.

Rutherford said he’s especially “bullish” on consumers being nudged to change their behavior. I’ve been using Google Flights to find lower-emissions options, but I wonder how many other consumers—most of whom don’t think about climate change for a living—do the same. And even if everyone sought out lower-emissions flights, would that make enough of a dent? Or do we simply need people to fly less?

The answer to that last question is, basically, yes. It’s an uncomfortable part of the conversation, Rutherford admits—especially given that most of the world’s policymakers are themselves super-fliers. “This fits into the big debate over collective action versus personal responsibility,” he said. “Long term, it’s a societal problem.”

Good News

Massachusetts announced last week that it was creating the country’s first green bank for affordable housing. The Massachusetts Community Climate Bank, created with an initial seed of $50 million from the federal government, will offer people living in low-income housing retrofits that help both decarbonize buildings and lower energy bills.

![]()

Bad News

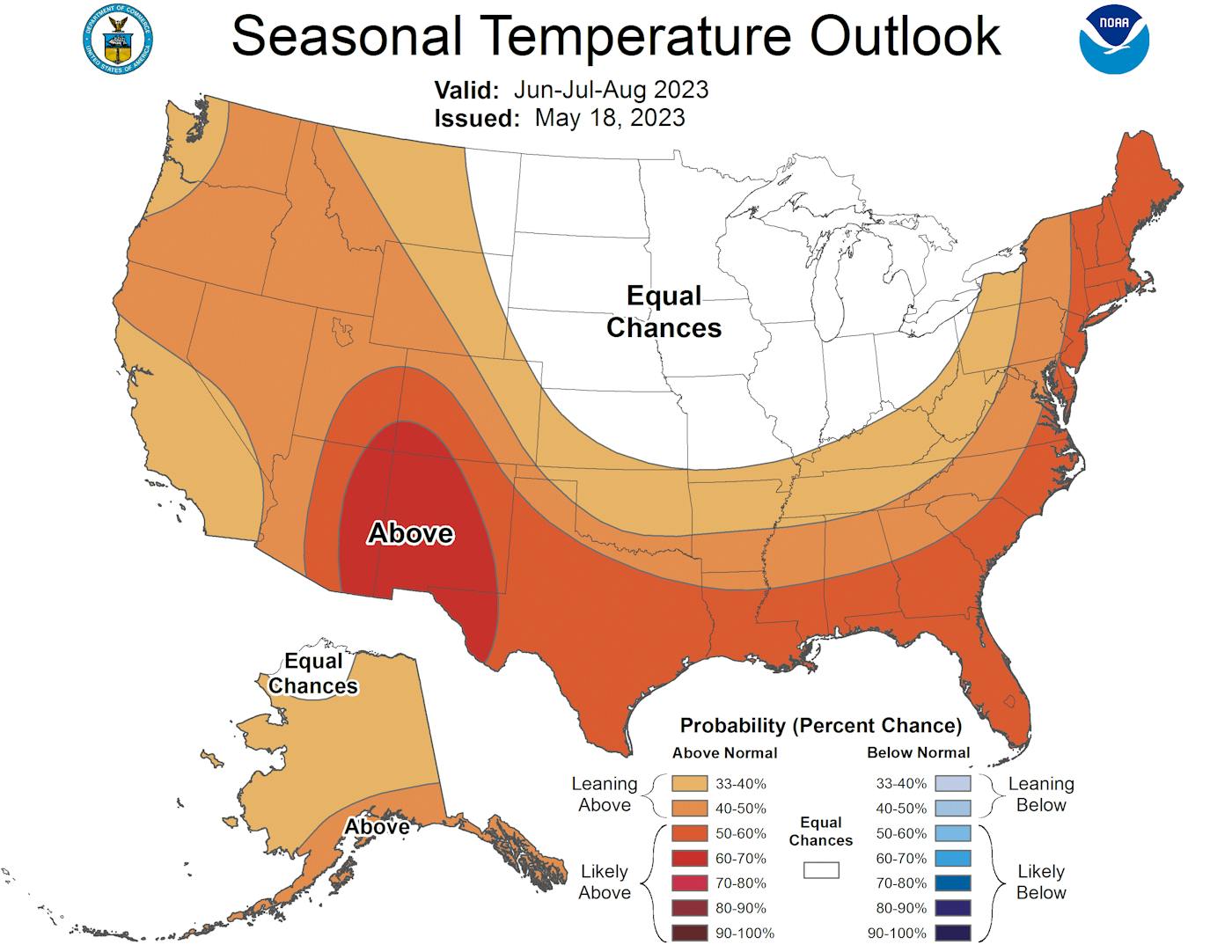

The world just keeps getting hotter and hotter. Global air temperatures briefly breached 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels—the bottom warming limit set by the Paris Agreement—in June.

Stat of the Week

103.3°F

That’s the temperature reached in early June in Baevo, Russia, where summer temperatures usually only get up to the high 70s or low 80s. Siberia is experiencing a record-breaking heat wave this month, and several places across the region have seen all-time highs.

Elsewhere in the Ecosystem

Out of Balance: How the World Bank Group Is Enabling the Deaths of Endangered Chimps

Carbon offsets aren’t the only problem. Biodiversity offsets—a practice where corporations can pay for damaging flora and fauna in one region by funding conservation elsewhere—can have unintended and devastating consequences. ProPublica reports on how one mining company’s offsets in Guinea are leading to the mass death of chimpanzees and putting residents in a nearby village in danger:

Offsets are “mainly an instrument to sanction perpetual destruction,” said Jutta Kill, a researcher and environmental advocate who’s studied conservation programs in the Global South.

While biodiversity offsets have been used by governments, banks and industries at least 13,000 times across 37 countries, these arrangements have been subjected to far less scrutiny than carbon offsets, which my investigations have found to be profoundly flawed.

I reviewed the literature on the tiny sliver of biodiversity offsets that have been studied and found that, at best, their records are spotty or unproven. At worst, they function as greenwashing for destructive industries.

Those associated with the World Bank Group are among the most controversial, because unlike most others, some enable companies to write off the lives of critically endangered species.

Read Lisa Song’s full report at ProPublica.

This article first appeared in Life in a Warming World, a weekly TNR newsletter authored by contributing deputy editor Molly Taft. Sign up here.

.png)

.png)

.png)