In the mid-1990s, when I was still a bookish teenager, my parents took me to Paris. It was the end of December; we would, before the trip was done, spend New Year’s Eve on the Champs Élysées—I was not yet old enough or self-snobbified enough to think it tacky, to think it anything other than magical. One evening, we went to Le Boeuf sur le Toit for dinner. There was a jazz pianist. A swept-back shock of dark hair, going very thin on top, beginning to gray. A salt-and-pepper, full-face beard and moustache. A sharp nose. Round glasses. My father elbowed me, leaned in, gestured subtly toward the stage. “Check it out. Is that Salman Rushdie?”

It’s become a little part of our own family lore. Remember the time we saw Rushdie hiding out from the fatwa as a lounge performer in Paris? I like to tell myself it was really him (Salman, if it was, D.M. me!), although I am pretty sure he was still living, mostly under guard, in London at the time, and I like to believe he would make a great story or novel out of it—a character, very much like Salman Rushdie, under a terrifying interdiction very much like the religious judgment against him, living autrement as a lounge act at a touristic modern incarnation of a once–avant garde Parisian cabaret.

In any event, Rushdie’s hiding and seclusion were often of a semiporous nature. He was—and is—a bon vivant and a bit of a starfucker. No shade. We live in an age of microcelebrity and “influence.” A few years before I went to Paris, he went onstage at a packed U2 concert in Wembley Stadium. He loves good food, politicians’ plaudits, proximity to wealth, and beautiful women. But because he wrote one book, ironically neither his best nor his worst but a mid-pack effort, which displeased the wrong people for reasons at once momentous and wildly petty, he really did have to temper the love of the good life with safe houses, guards, and armored cars. For decades! One book!

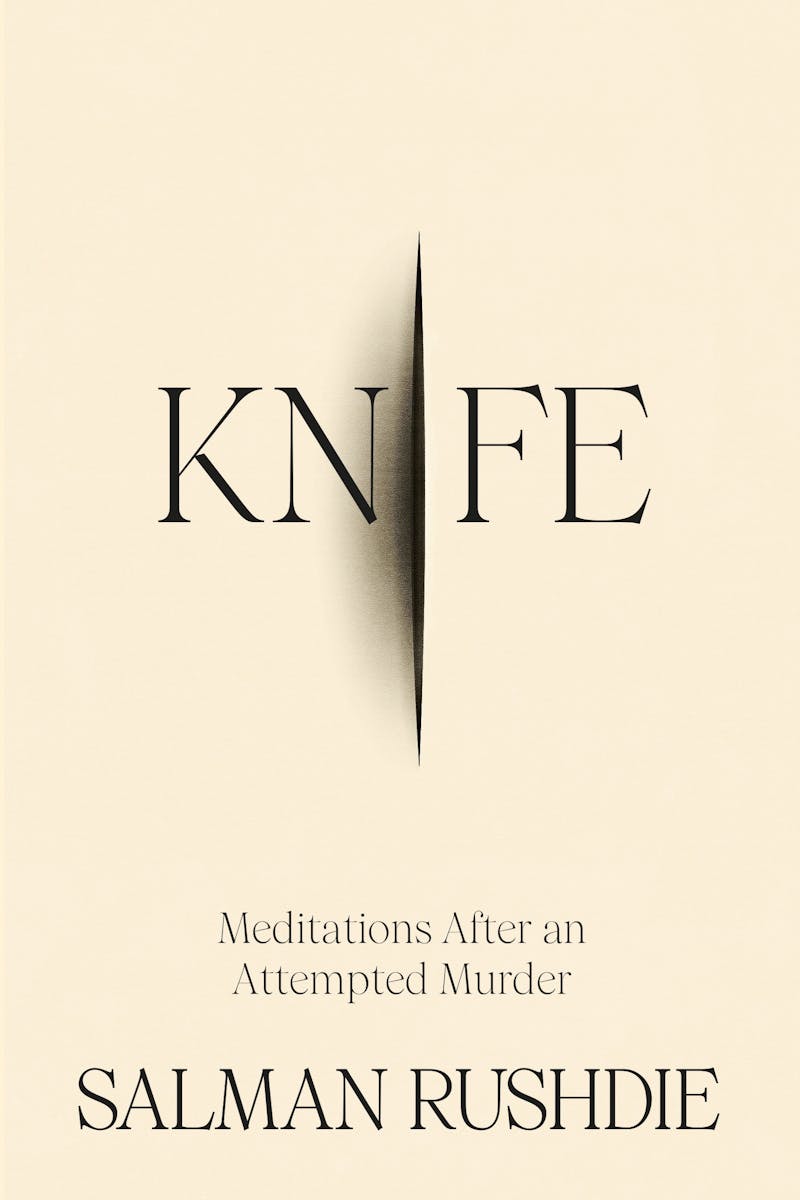

And yet it was only later, years later, after he had mostly emerged from armed guard, moved to the United States and become a citizen, remarried, gotten—by his own admission—rather old and a little too fat for his own liking; when, despite the “unfunny valentine” of the renewed Iranian fatwa against him each year, it seemed more likely that he might get canceled for his treatment of an ex than assassinated for a crime of blasphemy, that the assassin came. His “thought when I saw this murderous shape rushing toward me was: So it’s you. Here you are.” But then: “It struck me as anachronistic.” All those years, 33 in total, all that waiting, and finally a man with the knife that would become the title of Rushdie’s memoir—“meditation,” he calls it—arrives and stabs him, brutally, insanely, 15 times. Improbably, the author survives. As he recovers, he begins to contemplate his next novel, which he had already sketched out. But: “I saw that Andrew Wylie [Rushdie’s agent] had been right. Until I dealt with the attack, I wouldn’t be able to write anything else. I understood that I had to write the book you’re reading now before I could move on to anything else. To write would be my way of owning what had happened, taking charge of it, making it mine, refusing to be a mere victim. I would answer violence with art.”

“Why didn’t I fight? Why didn’t I run?” the author asks. (A misdirection of sorts: He did; there are defensive wounds on his hand.) “Why didn’t I act?” Like so many victims of violence, and in contrast to the very American fantasy of meeting violent crime with righteous counter-violence, Rushdie finds himself shocked into paralysis by the suddenness and savagery of the attack. Sentenced to death for his words, he had surely allowed himself to imagine it, and yet it was not as he’d imagined. The attack still surprised him. And what’s more: He lived. What a strange conundrum for a novelist—a failure, in a sense, of imagination. What would he make of this exceptionally Rushdian turn of fate—not a trained assassin, not a terrorist, but a basement-dwelling gamer, radicalized, it seems, by YouTube, coming at last for the famous writer who, after three decades in semi-hiding, felt comfortable enough at last to come give a public lecture at Chautauqua, New York, of all ridiculous places for an assassination?

The opening chapter, the description of the attack, the precise and harrowing clinical details of the damage to his physical body, unwind in spare blood-and-gore detail that would make Cormac McCarthy jealous. Rushdie writes of the procedures to repair his body, of the pain and indignity of physical and occupational therapy with little of the whoop and bombast and exuberance that are the stylistic marks of his most famous fictional prose, and it is very effective. Having gone through a much more modest round of physical therapy for a much less serious injury myself, I felt every unadorned, deliberately anti-poetic ouch. “Let me offer this piece of advice to you, gentle reader: if you can avoid having your eyelid sewn shut ... avoid it. It really, really hurts.”

Rushdie’s wife, the poet and artist Rachel Eliza Griffiths (who married Rushdie with little publicity or fanfare in 2021, and whom Rushdie plainly seems to adore) comes off as a heroic person, but the tale of their “meet cute” and swift courtship, upon which Rushdie lavishes considerable attention early on, comes off as very little more than a dinner-party anecdote: She was so pretty, he wasn’t paying attention and walked into a door! His nose was bleeding. She decided to accompany him in a taxi home. A fine, funny story over a glass of wine. Perhaps not the stuff of memoirs. He rehashes some complaints about critics who had been unkind to him in the past. He gripes about “freedom everywhere under attack from the bien-pensant left as well as book-banning conservatives”—your grouchy seventy-something cable-news uncle rather than a celebrated author and wit who has been mentioned as a candidate for a Nobel Prize.

There is, though, one chapter, later in the book, that intimates a grander project, and perhaps some future prospect of answering “violence with art.” In a chapter called, simply, “The A.,”— the moniker that Rushdie gives to his attacker—Rushdie imagines a series of conversations with his attacker, who had weirdly stated, after he was arrested, that he had attacked the author for being a “disingenuous” person. The conceit seemed foolish, wrong. A made-up colloquy with your own would-be murderer? In a memoir, a work of nonfiction, and—not to mention—while the young man still awaited trial, a trial at which you would very likely need to testify yourself?

I found it—to my surprise—to be quite strange and wonderful. The Rushdie who interrogates The A. is like my piano player. Not really Rushdie. The A. is not really the wannabe assassin, who, when he traveled to Chautauqua with murder on his mind packed a whole bagful of knives, spoiling himself for choice. They are both, the interrogator and interrogatee, ghostly, mental interlocutors for positions that cannot readily be reconciled, one standing for a loquacious and capacious postwar notion of art, free expression, progress, and sensuality while the other voices a seemingly older and more austere faith in a freedom born out of submission to the very real will of God. Rushdie—fake Rushdie, interrogator Rushdie—gives himself the literary allusions, the sharper eye for contradiction and hypocrisy, but then, he gives his quarry, his almost-killer, the best lines. “Listen: At school there’s this experiment with iron filings and a magnet. When you point the magnet, all the iron filings fall in line. They all point in the same direction. That’s what I’m telling you. The magnet is God. If you’re made of iron, you’ll point in the right direction. And the iron is faith.”

These dream dialogues point back to the central surprise of the book: Neither “the A.” nor the author is who we—or who they themselves—quite expected them to be. Rushdie is no longer some literary enfant terrible, no longer the man in hiding, no longer the famous party-hound and celebrity of middle age: He is a comfortable, married, upper-middle-class Manhattanite, settling into Flaubert’s maxim about living a regular and orderly life and saving violent originality for your books. How strange, and how compelling to find out that after everything, Salman Rushdie is just some writer.

The book then rushes to a rather pat conclusion. Yes, yes, happiness could reemerge after tragedy and pain. I don’t begrudge the author this message, or this ending, but I could not help but wonder if this swift return to regular life, to date nights and vacations, constituted a little bit of a narrative cop-out, and if the mind that could confront itself with the rigid and unshakeable faith of those imagined conversations with its own would-be exterminator might not come, if given more time, to a more ambiguous answer.

Rushdie chose, as the epigraph to this book, a quote from Samuel Beckett on Proust: “We are other, no longer what we were before the calamity of yesterday.” But Beckett also wrote, later in that passage, “Whatever opinion we may be pleased to hold on the subject of death, we may be sure that it is meaningless and valueless. Death has not required us to keep a day free.” For so long, Rushdie’s life and works, his fame and reputation, were shadowed—at least partially—by the singular and monumental fact of the fatwa. Then death came for him. And it missed! And after reading Knife, I am still left wondering and wanting to know more: how other he became after the calamity.