In the beginning there was nothing. Silence. Then: a bang. And then everything else. And though nobody was around (obviously) to hear the birth of the cosmos, the echoes of that primordial detonation linger, shaping matter and light and permeating the whole, vast, fathomless firmament. The universe, in a meaningful way, is made of noise.

Noise is, for Thurston Moore, singularly meaningful: He is obsessed with its implications, its possibilities, and its sheer noisiness. In the early 1980s, Sonic Youth—whose evolving lineup was based around Moore and fellow guitarist-songwriters Lee Ranaldo and Kim Gordon, who was married to Moore for nearly 30 years—was the squealing edge of the so-called “noise rock” movement. Drawing inspiration from the avant-garde and the hard-core punk underground, noise rock prized volume, atonality, and wild waves of amplifier feedback, provided by cheapo guitars played in odd, unconventional tunings. The premise, basically: What if they made a whole song out of the bad parts of songs? Noise rock took the ostensible defects of amplified rock music and made virtues of them.

From hard-core, noise rock borrowed a sense of confrontation, and a reclamation of the ugly. Drumsticks were jammed under fretboards; modified guitars were whacked against amps; and the music, such as it is, rises to impossibly loud, tinnitus-inducing pitches. Feedback had been deliberately deployed before, by artists from composer Steve Reich to the Velvet Underground, to The Beatles on “I Feel Fine.” But bands like Sonic Youth crafted whole sonic spectacles out of the conscious, wildly improvisational wielding of feedback and noise. In Sonic Youth’s music, noise was a texture, accruing like the layers of paint on a Rothko canvas. The sound challenged audiences and pushed dinky in-house P.A.s to their limits. “We were at war,” Moore declares, “with the soundmen of America.” Groups like Sonic Youth bucked good standards of signal-to-noise ratios. The noise was the signal.

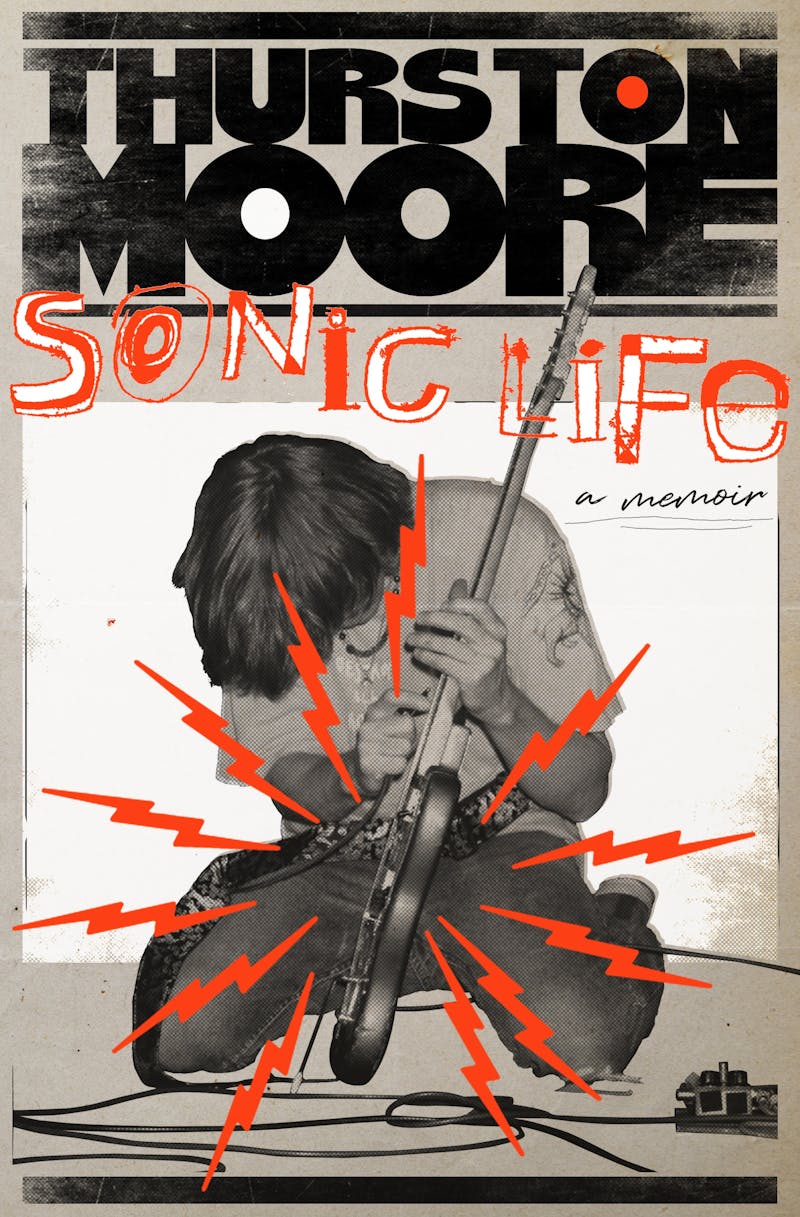

Moore’s new memoir, Sonic Life, may be accused of being too signal-driven. For all the messiness of his music, this account of Moore’s life is conspicuously tidy, assiduously painting Moore as a thoughtful, humble, and fundamentally shy person. He shuns the allure of sex and drugs (“just not a defining factor for me”) in favor of “a wholly other kind of eros than the one found by those blessed bed-hoppers.” No compliment paid to the band, or to Moore himself, is left unremembered (“Nirvana wore our T-shirts and sung our praises”). Even digs are framed as backhanded compliments: When Minutemen bassist Mike Watt tells Moore that “record collectors shouldn’t be in bands,” the diss ultimately redounds to the author’s benefit. The more he goes on in this vein, the harder it is to square the Thurston Moore of the book with the Thurston Moore who played in the singular band that was Sonic Youth.

Sonic Youth formed in 1981, when Moore and Gordon ditched their previous bands and linked up (musically and romantically). Lee Ranaldo, a veteran of New York underground “guitar orchestras,” would add far-out, experimental texture to the group: “three guitars melding, chasing, and spiraling into one another,” as Moore writes. Over early albums, the chaos and sheer noise of the group’s live shows settled into a more conventional (but still boundary-pushing) rock sound.

The band found fans in America’s emerging punk clubs, and in Europe, where they were feted as the next big thing. By 1988’s Daydream Nation, the band were standard-bearers of the indie underground that now included hard-core punk groups like Black Flag alongside more melodic, even tuneful groups like REM and The Replacements. (Critic Robert Christgau, an early doubter of the group, was forced to gulp and admit that Daydream Nation constituted a “philosophical triumph.”) Major labels came knocking. By 1990, Sonic Youth had signed with David Geffen, effectively charting the underground’s pathway into the byways of more MTV-friendly rock styles. Lollapalooza followed. And a Simpsons cameo. By 2008, the band was releasing compilations displayed exclusively at Starbucks coffee stores. Even more than Nirvana, Sonic Youth’s arc tells the story of American indie rock, and its move from the margins to mainstream, in miniature. But you’d never get this sense reading Moore’s book.

Sonic Life is basically a by-the-numbers rock star bio, about a dweeby small-town kid who falls in love with music, raids the cheap bins at records stores, cuts his hair to look like Iggy Pop, and, in the late 1970s, moves to lower Manhattan to make the scene. For its first hundred or so pages, Moore rattles off the names of bands he saw, like a birdwatcher recounting their life list: Patti Smith, Television, Suicide, New York Dolls, Siouxsie & the Banshees, The Nuns, Wire, PiL, Crass, Ut, DNA, 8 Eyed Spy, Bush Tetras—bored yet? He rubs shoulders with William Burroughs, Sun Ra, and Joey Ramone, casting himself as a Zelig-like figure in the New York underground he would, in time, come to rule.

Moore’s writing is often possessed of a grating imperiousness. He was “living in this city for the ineffable connection it afforded us,” he writes of New York City in the late 1970s, “the wild community of artists, poets and musicians giving voice to an environment rife with trash, chaos, and absurdity.” He is ahead of the curve on hard-core, on hip-hop, and on any other genre regarded charily by the snootier members of New York’s “seen-it-all” scenesters. “To walk into a CBGB matinee and see Bad Brains was to share a room with one of the greatest bands in the history of rock ’n’ roll beyond any doubt,” he writes, with the air of some conquistador of cool who believes he’s discovering something.

Of course, the thing about coolness is that it diminishes the minute

someone insists upon it. And Moore’s repeated invocations of his impeccable

taste, his progressive politics (he spends two pages in anguish over the

feminist, and anti-feminist, implications of hanging a nudie calendar on his

apartment wall), and his own downtown art-punk bona fides can feel a

little unrelenting. Especially because Sonic Youth and their music are already

synonymous with a certain strain of disdainful cool. Of course, not everyone

bought it. In his classic chronicle of the American indie rock underground, Our

Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad

notes that certain segments of the scene regarded the group as “charlatans

borrowing promotional ideas from the art world to browbeat the underground into

building a consensus of cool around them.”

It wasn’t just their mix of hypnotic guitar noise and punk-rock energy. Their lyrics conveyed a sneering nihilism (“I can’t get laid ’cause everyone is dead,” Moore mewls on “Stereo Sanctity”). They built a totalizing aesthetic, trading in images of serial killers, a borrowed beat lexicon (“yr,” “becuz,” “kool”), and art school meta-jokes—the cover of their 1995 record Washing Machine features two fans wearing Sonic Youth T-shirts; the band also released its own T-shirt emblazoned with the image of a woman wearing a Sonic Youth T-shirt.

Like all truly cool

bands, basically anything Sonic Youth did became cool, by mere virtue of their

doing it. They got away with underground no-nos: like sending promotional clips

to MTV, covering Madonna tunes, or signing with a major label. Their shrugging,

whatever-man attitude managed to insulate them from the standard sell-out

criticisms. And that attitude, as Azerrad has written, proved particularly

useful to music industry honchos, among whom there existed, “an unspoken understanding that

[Sonic Youth] were so cool that their chief function was as a magnet band, an

act that would serve mostly to attract other, more successful bands.” This

status wasn’t lost on their contemporaries either. The pioneering riot grrrl

punk band Bikini Kill sang:

If Sonic Youth thinks you’re cool

Does that mean everything to you?

Moore, of course, quotes these lyrics as further evidence of his group’s

“role model status.” He frames everything—from Sonic Youth’s move from

exploratory wailing to four-minute rock singles, to the changing power dynamics

of the band—as natural and intuitive, never opportunistic or crassly

commercial. Perhaps that’s true. But the constant flexing, and general lack of

reflection, grows tedious. One presumes that anyone reading Thurston Moore’s

autobiography already believes that Sonic Youth is a great, and very

influential, band.

Where Sonic Life really sings (or squeals) is as an encyclopedia of noise, and noises. Moore is keenly attuned to the sounds of the world around him. And he describes them with great relish. An early encounter with the primitivist garage rock classic “Louie Louie” altered his whole “soundworld.” Fledgling excursions on an electric Stratocaster produced “squalling, squealing, screeching electric noise.” At one point he dreams of making “wet noise” (yuck). Heroes and contemporaries are themselves praised on the basis of their purely sonic qualities. A 1976 Lou Reed concert produces “golden frequencies of music streaming and whirling around.” New York violinist Boris Policeband is “a living noise sculpture.” A Blondie show at CBGB opened a portal to “a wholly new sonic dimension.” Punk rockers Mission of Burma operate in “sonic overdrive.” A new drummer has the effect of recalibrating a band’s “sonic engine.” A bodega refrigerator captivates, with its “subsonic drone.” Everything is sonic-this, and sonic-that.

Sonic Youth itself is not a mere band, but a “sonic democracy.” Their own music is a “psychedelic heavy metal no wave rainbow.” Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, meanwhile, purvey “swap-drench gothic gush.” It’s like Moore is battering his thesaurus to shake out fresh new synonyms for noise, and sound, and a whole broad concept of the sonic. And when no words exist, Moore invents his own. “Crunge,” describing a type of amateurish, high-volume guitar yowling, is a great one.

His more philosophical reflections on the artistic possibilities of noise are also worthwhile. Avant-garde composer Glenn Branca, who recruited Moore and Ranaldo for his guitar orchestras, “tore away at the fabric of reality, creating singular moments in which musicians and audiences could—when the alignment was just right—experience extrasensory, soul-shifting explosions.” An early Sonic Youth performance has “our three guitars melding, chasing, and spiraling into one another.” If these passages scan as a bit hyperbolic, or even cheesy, it is only because Moore seems genuinely in love with noise. He comes by his professorial tone honestly, as both dean and lifelong student of a sound he practically invented. Or rather, “co-invented.”

What most undermines Sonic Life is not its author or voice.

It’s the existence of another, better, book about Sonic Youth, its associated

personages, and its tangled interpersonal dynamics.

Kim Gordon’s Girl in a Band was published in 2015, in the more immediate aftermath of Sonic Youth’s breakup, which was itself precipitated by the breakdown of Gordon and Moore’s marriage. In brief: Moore cheated on Gordon with a poet and publisher 20 years his junior. In her book, Gordon is unsparing. She calls Moore “a coward” and “a serial liar,” whose actions turned their lives into “another cliché of middle-aged relationship failure.” As her memoir’s title suggests, Gordon cast herself as a little on the outside of her own band. This perspective grants her a clarity, both about her experience and her music: “The girl anchors the stage, sucks in the male gaze,” she writes of her role in Sonic Youth, in what could also double as one of her acerbic lyrics.

Moore shows little interest in revisiting the breakup. The affair, and subsequent dissolution of the band, doesn’t figure until his book’s last pages. Naturally, Moore has his own spin on the infidelity: “We kept our communion to ourselves to some time, before eventually coming out with the news.” (In Gordon’s telling, she basically badgered him into a confession, after coming across a trove of incriminating correspondence.)

“The circumstances that led me to a place where I would even consider such an extreme and difficult decision,” Moore writes of his split, “are intensely personal, and I would never capitalize on them publicly, here or anywhere.” He’s entitled to his privacy, of course. But this reticence, framed as a form of respect, raises another, more fundamental question: Why write a whole book about your life if you don’t like talking about yourself?

For decades, in the

minds of their fans, Moore/Gordon were an inseparable dyad. She was the

intellectually oriented aesthete who wrote

tour diaries for Artforum. He was the sneering punk who shoved into audiences, heart

on his sleeve. But their books suggest that very much the opposite is true.

Gordon managed a frank, ruthless accounting of her own life and feelings. Moore

seems entirely more at ease talking about things outside of himself: other

musicians, other records, other scenes, the rattle and hum of a convenience

store fridge, droning subsonically. The raw, unselfconscious intensity of a

musician who boasts, on several occasions, about slicing his fingers on guitar

strings because he’s caterwauling too ferociously is, in these nearly 500 bound

pages, nowhere to be found.

Maybe that kind of revelation is beneath the standards of hip, downtown disaffection that Moore worked so diligently to cultivate. Maybe there’s just

not much there. Or, most likely, Sonic Life embodies a fact of so many

musicians’ memoirs: that whatever they have that’s worth saying is better said

through the music itself. Put on Bad Moon Rising, or Daydream Nation,

or the epic, mesmeric, 20-minute-long “Diamond Sea.” There you’ll find a

Thurston Moore that’s passionate, enthralling, and altogether more engaged.

While remaining just as cool.