A man walks across a barren landscape. He may be wounded, or ill, but he is strong enough to survive. As he walks, he pays close attention to the landscape, noting changes in the wind and light, scanning for traces of animal or man. He must be careful—his very life depends on it. For the man, though strong and quick, is vulnerable: He is utterly alone, far from home and far from help, blessed and cursed by solitude.

This man is the typical Cormac McCarthy hero—as well as the typical anti-hero. He is John Grady Cole, the teenage protagonist of All the Pretty Horses (1992), hitchhiking from a Mexican prison to a lush hacienda, where he hopes to see his love again. He is Anton Chigurh, the indestructible assassin in No Country for Old Men (2005), who walks away from gunfights and car wrecks like some modern-day Achilles. He is also Chigurh’s prey: the welder Llewelyn Moss, who scuttles across the Texas desert under the cover of night, trying to avoid those who want him dead. He is the nameless father in the dystopian novel The Road (2006), who, dodging cannibals and coughing up blood, marches with his young son to the sea.

Bobby Western, the protagonist of McCarthy’s new novel, The Passenger, at first appears to be a departure from type. A race car driver turned salvage diver, Bobby is socially embedded and seemingly beloved. He plumbs the depths of the Gulf of Mexico with his buddy Oiler. He shoots the shit with a loquacious drug dealer named Long John Sheddan, who refers to him affectionately as “Squire.” He frequents a bar in the French Quarter of New Orleans where everyone knows his name. For him, unlike for other McCarthy men, solitude proves elusive—he even makes a friend while living on an island off the Iberian Peninsula.

We soon learn, though, that Bobby sees himself as a man apart. He’s in mourning for his younger sister, Alicia, a brilliant mathematician who died by suicide eight years earlier, in 1972; we glimpse her inner life—primarily her hallucinations—in italicized interludes. He’s private, given to solitary walks, and he speaks with real affection only to his cat. When government agents show up with some questions for Bobby—forcing him to flee from his apartment, then from New Orleans, then from the United States altogether—he accepts his fate without much resistance. It’s as if he’d always known that he’d end up alone—or believed that he already was.

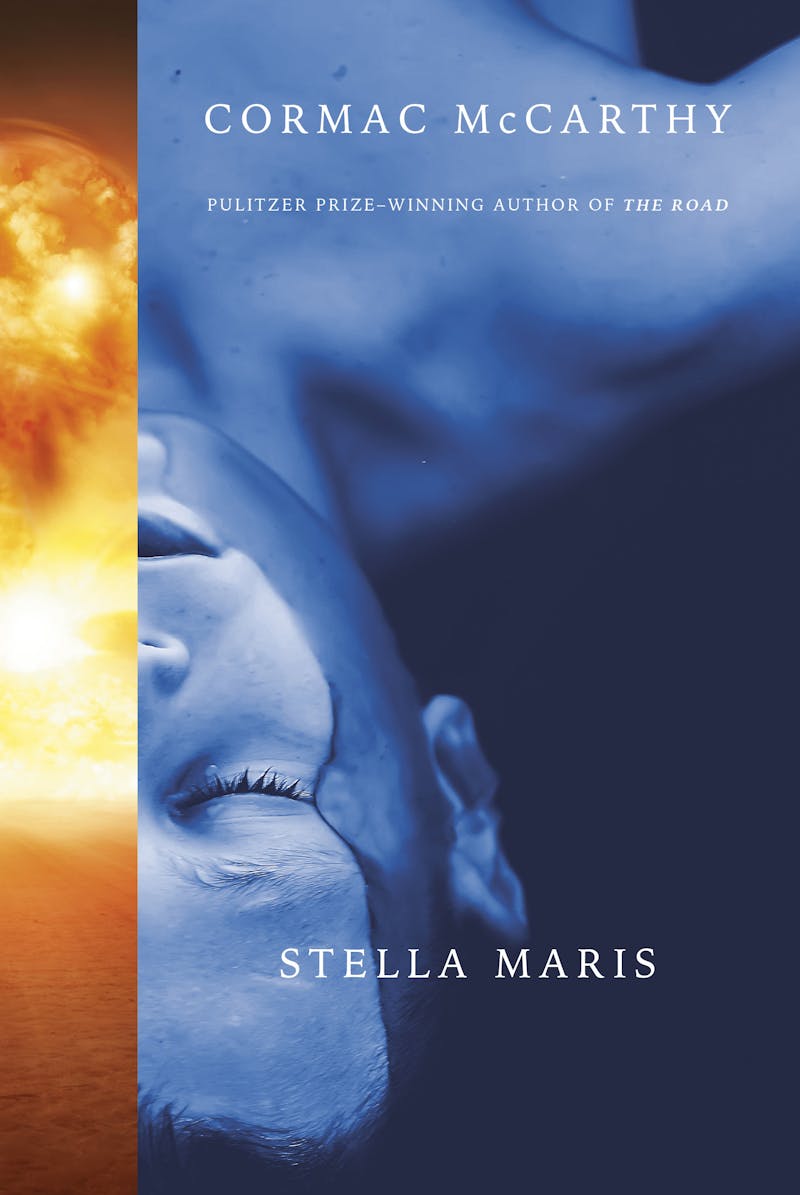

Such is the paradox of The Passenger, a novel at once highly attuned to the pleasures of collective life and resistant to the very idea of it. Unlike the violent, stylized books for which McCarthy is best known, this new novel is loose, warm, colloquial. It explores the sustaining, if impermanent, bonds formed among male friends. It’s full of theories and anecdotes, memories and stories, all voiced by some of the liveliest characters McCarthy has ever crafted. The Passenger is McCarthy’s first novel in over 15 years; its coda, Stella Maris, is published in December. Together, the books represent a new, perhaps final direction for McCarthy. The Passenger in particular is McCarthy’s most peopled novel, his most polyphonic—and it’s wonderfully entertaining, in a way that few of his previous books have been. It is also his loneliest novel yet.

McCarthy has built a reputation as a recluse. A college dropout and an autodidact, he’s largely refused the social and professional obligations that occupy most writers. Like Thomas Pynchon and J.D. Salinger, he eschews interviews. Unlike many writers, he doesn’t write book reviews, or lecture, or teach. Before he cracked the bestseller list with All the Pretty Horses, his books sold poorly; his second ex-wife claims that the couple lived in “total poverty,” bathing in a lake and subsisting on beans. (McCarthy is thrice-married and thrice-divorced.) During these lean years, he relied on the largesse of literary institutions, which awarded him the occasional fellowship. When he got news that he’d won the MacArthur “genius grant,” in 1981, he was living in a motel in Knoxville, Tennessee—a step up from his prior living quarters, where he’d made do without electricity.

Thus, when McCarthy writes about vagabonds and drifters, men without steady jobs who live largely by their wits, he knows whereof he speaks. His early Appalachian novels—The Orchard Keeper (1965), Outer Dark (1968), Child of God (1973), and Suttree (1979)—are all informed by his experiences of modest country living, and, less directly, by a childhood spent in Knoxville. After moving to El Paso, Texas, in 1976, McCarthy shifted his attention to the cowboys and criminals of the American West. Blood Meridian (1985), a historical mock-epic indebted to Herman Melville, follows the escapades of a protagonist known only as “the Kid,” who joins a paramilitary scalping gang as it fights purposeless skirmishes along the U.S.-Mexico border. The Border Trilogy (All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, Cities of the Plain), published over the course of the 1990s, presents a more romantic view of the region. The novels, set in the mid-century, focus on working-class heroes Cole and Billy Parham as they commune with animals and care for their literal and figurative brothers. McCarthy’s Western phase culminated with No Country for Old Men, a taut crime novel later adapted for the screen by the Coen brothers. It updates the writer’s great themes—lawlessness, fatalism, and “mindless violence”—for the present day.

Though he has an eye for a region’s ecosystem and an ear for its dialect, McCarthy’s novels are not conventional works of realist fiction. Instead, he carries on the tradition of American literary modernism. His sentences are either ornate and labyrinthine, with a tendency toward the baroque, or they are simple and action-oriented, accruing meaning through parataxis. Consider this description of a newborn’s cry, from Outer Dark:

It howled execration upon the dim camarine world of its nativity wail on wail while he lay there gibbering with palsied jawhasps, his hands putting back the night like some witless paraclete beleaguered with all limbo’s clamor.

And contrast it with this passage from The Road, in which the father builds a fire:

The wood was damp but he shaved the dead bark off with his knife and he stacked brush and sticks all about to dry in the heat. Then he spread the sheet of plastic on the ground and got the coats and blankets from the cart and took off their damp and muddy shoes and they sat there in silence with their hands outheld to the flames.

The first recalls William Faulkner, while the second might have been pulled from one of Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories. Your enjoyment of McCarthy will likely depend on your tolerance for these two canonical male writers. (As it happens, I like them both.)

Like Faulkner, McCarthy is an American mythmaker; in his early novels, he constructed his own Yoknapatawpha County in the Appalachian hills. But more than Faulkner, McCarthy is a religious writer. His characters are pilgrims and prodigal sons. They go on quests; they come face-to-face with evil; they fall from grace. “One character resembles a “medieval penitent”; two others, clothed in rags, are compared to “mendicant friars.” Others are “replevied by grim miracle”; they martyr themselves; they seem to rise from the dead.

McCarthy doesn’t call upon Christianity in order to advance a moral vision—if anything, the opposite. His novels suggest that evil has always been with us and always will be, whether it takes the form of a group of armed Comanche—“a legion of horribles”—descending a hill on horseback, or a roving gang of cannibals with human flesh stuck between their teeth. In such a world, he suggests, all one can do is act with integrity and generosity, without expectation of mercy or reward. The most admirable characters in McCarthy’s fiction are the unnamed laborers and poor country folk who share their meager rations with traveling strangers, no questions asked. Like children and saints, they see the world as replete with mysteries that surpass human understanding.

Sometime in the 1990s, McCarthy began spending time at the Santa Fe Institute, an interdisciplinary research center that primarily caters to scholars in the sciences and that gives them a chance to explore complex questions together. Almost immediately, the literary nomad felt at home. A naturalist with wide and varied interests, he started attending scientific lectures, where he purportedly asked sharp questions. He became a senior fellow at the institute, then a trustee. He formed close friendships with the resident fellows and began making over the institute’s interiors to his specifications, adding gilt mirrors and dark wood. Though SFI spokespeople tout the value of having a “humanist” among them, McCarthy, who disdains both other writers and contemporary fiction (he calls today’s novels “not readable”), insists that he’s more like the other fellows than one might expect. “I’m not here because I’m a novelist,” he told an interviewer. “I’m here because I like science, and this is a fun place to spend time.” Still, he’s written several novels at SFI, where he has an office and a typewriter.

The Passenger and Stella Maris are the first books to demonstrate SFI’s significant influence on McCarthy’s writing life. Both books are about scientific research and ethics, and both contain fairly technical discussions of mathematical concepts. Bobby and Alicia display aptitude in the sciences—Bobby in physics, and Alicia in high-level mathematics. The siblings seem to have inherited their abilities from their late father, who was one of the developers of the atomic bomb. For Bobby especially, the bomb’s invention functions as something like original sin. When the government begins investigating him, supposedly in connection with a mysterious plane crash that occurs at the beginning of the novel, Bobby can’t help but think of himself as an essentially guilty party. His maternal grandmother sometimes suspects that the family is cursed.

Bobby, like McCarthy, finds solace not in romance or family, but in a community—and in this case, a community composed mostly of men. He spends much of the novel hanging out with his friends and listening to their tall tales. His diving partner Oiler tells him about blowing up elephants in Vietnam. His friend Sheddan describes how a recent drug deal went bust. There’s a good amount of male bonding through sexual bragging: We read about a blow job in a phone booth, sex with older women, and a girlfriend who liked to have sex in “rabbit suits.” (The banter and barroom chats recall the atmosphere of Suttree, McCarthy’s most autobiographical novel.) The voices of these boisterous men take over the novel, pushing McCarthy’s crafted narration to the margins. Reading the book, I wondered if I was getting a glimpse of communal life at SFI: fun, spontaneous, undirected.

This is the community that Bobby stands to lose, and for no apparent reason. The novel begins as a kind of classic postmodern caper: A charter plane has crashed, and one of the passengers is missing. Federal agents repeatedly question Bobby, who examined the wreck, and who knows nothing about the plane or the passenger. But what starts out as the story of yet another FBI stitch-up, with shades of Don DeLillo, soon becomes a tragedy, barreling toward its inevitable end. Bobby, who shoulders the blame for his sister’s death and for his nation’s war crimes, anticipates any suffering as fitting penance. Midway through the novel, he sits in a church pew and conjures the images of the atomic bomb’s explosion and its aftermath: the “mycoidal phantom blooming in the dawn like an evil lotus”; the “burning people” who “crawled among the corpses like some horror in a vast crematorium”; the birds that exploded in the sky and fell “in long arcs earthward like burning party favors.” How can a person atone for such cruelty? Is the “loss of those you loved” sufficient?

The novel tests this proposition by slowly stripping Bobby, a Job-like figure, of all his friends and companions. A casual friend named Lurch dies by suicide early in the novel, gassing himself in his apartment. Oiler then dies on a dive in Venezuela. Sheddan eventually dies of hepatitis C and signs off with a final note to Bobby, thanking him for his friendship and reminding him that “suffering is a part of the human condition and must be borne.” Even Bobby’s cat, Billy Ray, disappears following an IRS raid on Bobby’s apartment. Each loss is a reminder of the one that came before and a rehearsal for those yet to come.

Soon enough, Bobby loses everything. The government impounds his car, then freezes his assets. A private eye named Kline encourages him to go on the run, reminding him that no American is safe from the deep state. Bobby moves first to a “shack out on the dunes” in Mississippi, where he lives off roadkill and walks naked on the beach, then heads north to Idaho, where he settles in an abandoned farmhouse stocked with canned food. Finally, he sells an expensive violin left to him by his sister and uses the money to flee the country. He ends up “the last of all men who stands alone in the universe while it darkens around him.”

Thus, over the course of the novel, Bobby transforms into the typical McCarthy hero: resigned, resourceful, and fundamentally alone. But unlike his predecessors, who shunned society and lit out for the territory, Bobby is bereft, lonely. Though he accepts loneliness as man’s inevitable condition—“every remedy for loneliness only postpones it,” as Sheddan’s ghost puts it at one point—he can’t help but feel it keenly. He had come to depend on the company of men to stave off his deep and inescapable grief. “The voices were like a balm to him,” Bobby reflects at one point. “A community of men. A thing all but unknown to him for the greater part of his life.”

To say that McCarthy’s fiction is male-dominated is a bit like saying that Jane Austen favors drawing rooms, or that Moby-Dick takes place on the sea. Women appear infrequently in his novels, usually in the guise of the beautiful beloved. (There are also a few bad mothers, such as John Grady Cole’s, who dares to pursue a career on the stage.) They are almost always minor characters, thinly rendered and unconvincing. Female animals are portrayed with more complexity and tenderness. In The Crossing, for instance, a she-wolf has something of a starring role.

In a 2009 interview, McCarthy told The Wall Street Journal that he was working on a novel “largely about a young woman,” and that he’d been “planning on writing about a woman for 50 years.” If Stella Maris, the 200-page coda to The Passenger, is the product of all that planning, then it’s a disappointment. Told as a series of conversations between Bobby’s sister, Alicia, and her psychiatrist, Dr. Cohen, the book continues a project McCarthy began in a 2017 essay for the science magazine Nautilus, in which he theorized about the nature of the unconscious. (Portions of the essay are reproduced here nearly verbatim.) As a work of fiction, and particularly as a close study of a female character, it doesn’t succeed. But as a window into a great writer’s intellectual preoccupations, Stella Maris is invaluable.

Set in the last year of her life—eight years before The Passenger begins—the book finds the beautiful, “possibly anorexic” Alicia institutionalized at Stella Maris, a residential facility for psychiatric patients in Wisconsin. She’s a doctoral student in mathematics at the University of Chicago, but she’s recently become disillusioned with her chosen discipline and has paused her thesis work in topology. She’s also grieving what she believes to be the imminent loss of Bobby, who, at this point in their shared history, is on life support in Italy following an accident on the racetrack. Like Bobby, she tries to avoid her grief by engaging in conversation. But unlike Bobby, a consummate listener, Alicia talks—about quarks, about the Manhattan Project, about Berkeley’s A New Theory of Vision, about everything except her brother and her inappropriate romantic love for him, a love that he seems to reciprocate. (This incestuous, though never consummated, romance reworks the central plot of Outer Dark, in which Rinthy Holme, McCarthy’s most compelling female character, bears her brother’s child.) Stella Maris is thus a neat mirror of The Passenger: It fills in gaps in Bobby’s story and shows us the siblings’ shared history from Alicia’s point of view.

In The Passenger, Alicia is a cipher—all the more intriguing for being inaccessible to the reader. In Stella Maris, McCarthy lifts the veil on his mysterious creation. But what’s revealed is a shallow portrait of a troubled young woman, clichéd in some places and unfocused in others. Alicia’s gender doesn’t seem to shape her mind, or her life, in any meaningful way. Aside from a few quips about doctors who might have molested her, and a brief reference to the paucity of women in mathematics, Alicia might as well be anyone with library access and a head for numbers—or, indeed, McCarthy himself. Through Alicia, McCarthy pontificates about some of his favorite intellectual puzzles: Why does the unconscious communicate with us in images and in dreams, rather than in language? Can a person with no head for numbers be considered intelligent? The book nicely complements some of the intriguing remarks McCarthy has made during his rare interviews and gives us further insight into him, if not quite into his female creation.

If the stories in The Passenger are supplemental in the best sense—they serve no purpose other than entertainment—then Stella Maris is a less welcome supplement. Though it enriches our understanding of McCarthy and his influences, it undercuts the pathos of the novel that preceded it. One wishes that McCarthy had left Alicia mysterious and unknowable, a void that supports, even creates, the structure that surrounds it. She’s best seen as presented on The Passenger’s first page, hanging among the winter trees “with her head bowed and her hands turned slightly outward like those of certain ecumenical statues,” beguiling even in death.

Death, or the looming threat of it, does something to a writer’s style. After he was diagnosed with leukemia in 1991, the late literary scholar Edward Said grew increasingly interested in what he, following Adorno, called “late style,” that is, “the way in which the work of some great artists and writers acquires a new idiom towards the end of their lives.” Said identified two different kinds of late style: There was the late style of Shakespeare and Verdi, marked by “harmony and resolution,” and then there was the late style of someone like Ibsen, whose last work evinced “intransigence, difficulty and contradiction.” Said found the latter more interesting for its refusal of closure. “It is a sort of deliberately productive unproductiveness, a going against,” he wrote.

For a time, it appeared that McCarthy, now 89, would be a harmonious late stylist. Despite its horrors, The Road is a serene work, formally coherent and morally simplistic. The father and son are “the good guys,” the cannibals are “the bad guys,” and “goodness” finds the boy at the novel’s end. There are no lapses in tone, no digressions or contradictions. Is it any surprise that this is the novel that won him the Pulitzer Prize?

The Passenger, however, establishes McCarthy as a more interesting late stylist; it is the great achievement of his old age. It’s episodic and stylistically uneven, confusing and contradictory, and marked by what Said called a “sense of apartness and exile.” It’s the kind of novel you might write if, like McCarthy, you regularly enjoyed long lunches with your friends at the SFI, all the while knowing that each of them would soon leave you, or that you would leave them. It’s the kind of novel you’d write to remind yourself that each of us dies—and perhaps lives—alone.

The last pages of the novel find Bobby walking alone on a cold, foreign beach. He sees a figure before him and briefly hopes that this person might “fall in beside him”—but she is an old woman en route to visit her daughter, and he lets her walk on. The image recalls another scene on a different beach, this one in Mississippi, in which Bobby takes it upon himself to protect migratory birds who come ashore at the end of their journey across the gulf. McCarthy, ever exacting in his descriptions of the natural world, lists them by name: “Weary passerines. Vireos. Kingbirds and grosbeaks.” They lie on the beach exhausted, vulnerable. “You could pick them up out of the sand and hold them trembling in your palm,” McCarthy writes. “Their small hearts beating and their eyes shuttering.” The birds are at the end of one thing, and the beginning of another. Like all things mortal, they linger on Earth for a moment, then they take their leave.

This article has been updated.