Anyone who wants a systematic vision of how deeply the British middle class distrusts itself need only read Agatha Christie. In nearly 70 novels and more than 150 short stories, she imagined a series of claustrophobically cloistered middle-class villages and island-like communities (a cruise ship, a hotel, a passenger train, and in her most famous novel, And Then There Were None, an actual island), in which almost everybody is up to no good and almost any prominent person appears capable of plotting devious assassinations of their neighbors and relatives for the pettiest of reasons—usually money.

These insular, generally inbred fictional spaces (not unlike the closed-circuit token box of suspects, rooms, and weapons provided by the board game Clue) were almost entirely inhabited by utterly English types: doctors, lawyers, bankers, businessmen, actors and actresses, lords and ladies, and even policemen. Sure, there are plenty of servants roaming the crime scenes, but at the end of the day, they are inevitably blameless—leaving the profession of murder to those who run the society in which they merely serve. In a Christie novel, violent murder might happen at any moment—and yet the meals and tea still arrive on time, the beds are duly turned down, and the gardens properly managed.

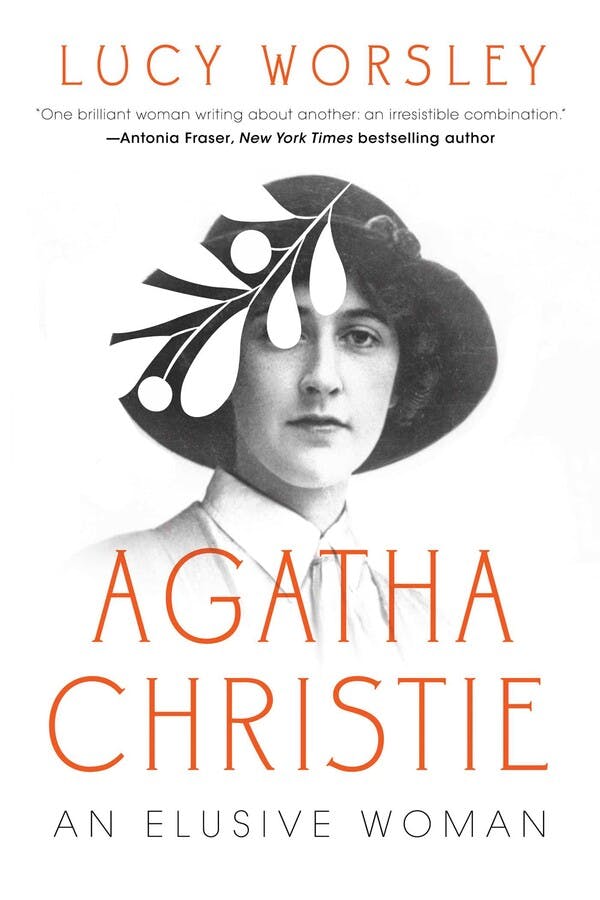

One of the great pleasures of these novels is their repetitive nature, and according to Lucy Worsley’s new biography, Agatha Christie: An Elusive Woman, Christie’s life was a continuous yearning for a return to childhood pleasures. In that desire, she was not unusual. It was, however, her manner of conjuring those pleasures—through a signature mix of charming settings and cold, logical violence—that presents a mystery, since few authors have managed to assemble a body of work at once so comforting and so emotionless, so quaint and orderly and yet so saturated with cruelty.

Born in 1890 to a wealthy Irish mother and American father, Christie lost many of the things she loved at an early age. Her father frittered away the family fortune, and after his early death, her older siblings moved out, and her mother went a bit mad. Then she was sent away to school, leaving behind the lush garden of her family estate overlooking the English seaside town Torquay—a privileged and “secret” garden that she would never enjoy the same way again. As she confided to her second husband in 1944: “Sometimes I feel very homeless. I find myself thinking ‘I want to go home’ and then it seems to me I have no home—and I do long for Ashfield. I know you didn’t like it—but it was my childhood’s home and that counts.”

For a long time, Christie felt that her stability had been torn away; and yet she possessed a passionate, indefatigable quality that would carry her through the rest of her life. Her first Hercule Poirot novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), was rejected for four years by multiple publishers, and after it finally appeared, she swiftly began producing one or two books a year—even more during periods of war and/or divorce, when her life was at its most tumultuous. She found escape through writing stories as much as her readers did through reading them—and she tended to produce her best work when her world was most worth escaping.

Her first marriage to a young military officer was a passionate one, but passion was never kind to Christie (or to her characters). When her husband left her for a younger woman in 1926, Christie crashed her car in a quarry and disappeared for an 11-day private holiday at a spa hotel in Yorkshire. The intense newspaper coverage was surprising, since Christie was only a modestly successful writer at the time; at one point, her disappearance inspired up to a thousand police officers and many thousands of members of the public (including Dorothy L. Sayers) to beat the brush in various parts of the countryside searching for her body, and Arthur Conan Doyle enlisted his favorite spiritualist to track Christie down through the use of one of her gloves.

The spiritualist soon reported that Christie wasn’t “dead as many think,” which proved him a far more capable tracker than Guildford police constable William Kenward, who devised a series of theories almost as preposterous as those in a typical Christie novel—that she had been murdered by her husband, or staged her disappearance in order to pin her murder on him, or vanished simply to promote her latest novel, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). Eventually, residents at the Yorkshire hotel began to notice a resemblance between their fellow holidaymaker and the newspaper photos and informed her estranged husband, Archie, who came to collect her. He later explained her actions as the result of “amnesia,” another hackneyed literary device that was almost certainly untrue. When they were divorced a few months later, Christie lost her home for a second time.

Christie’s fictional universe (like that of her many emulators) provides the safest possible space for readers to inhabit, and every book is reliably different from every other one in almost exactly the same way—which is probably why these stories of human slaughter are, more often than not, labeled as “comforting” by those who enjoy them, just as “a Christie for Christmas” was once one of publishing’s most successful refrains.

First, of course, there’s the introduction of principal suspects at a party or church function. Then the inevitable murder, which arrives shortly after several local conflicts are mapped out—adulterous liaisons, the squabbles of relatives over estates, and half-forgotten crimes from the past. But while the initial corpse arrives quickly, and is often followed by more, each victim is politely assassinated off-stage, and the description of each body is relatively bloodless. (The worst you might say about the corpses, as Auden put it in his affectionate structural map of the typical murder mystery, “The Guilty Vicarage,” is that they seem “shockingly out of place, as when a dog makes a mess on the living room carpet.”) Even when victims are shot, stabbed, poisoned, or bludgeoned, they remain discreetly off-camera, in order to be unemotionally examined by doctors, coroners, and cops who aren’t concerned with detailing violent contusions, sexual defilements, and torture implements (as they might well do in a typical Patricia Cornwell or Scott Turow); rather they are only concerned with the broken body’s proximity to doors and windows, half-incinerated notes left behind in ashtrays, and conflicting evidence regarding the exact time of death. (It’s amazing how often these victims die contiguous to a broken clock or wristwatch.)

Then, with the arrival of the detective (such as Miss Marple, Hercule Poirot, or Inspector Battle—though there are plenty of one-off detectives in individual novels as well) the clues rapidly proliferate; multiple maps of the homes and gardens are produced and various theories propounded. But at the end of the day, no matter how closely the clues are examined or how intricately the theories are developed, the most important information (usually pertaining to motive, a secret will, or some train timetable misprint) isn’t revealed by the detective until they have gone off somewhere and brought it back—and it usually turns out to be some secret they have been privy to all along.

As Julian Symons argued in Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel, each novel in the mystery genre—raised from healthy seedlings planted by Poe, Doyle, and G.K. Chesterton—assembles puzzle-piece fragments of truth, testimony, locked rooms, and forensic riddles that permit “no emotional engagement with the characters.” It may have been Christie’s deep reticence that drove her to create such isolated fantasies of wholeness. (The beginning, middle, and end of every story forms a perfectly shaped narrative that is about as Aristotelian as you can get.) No wonder Christie’s preferred form of murder is poison—something that can be administered dispassionately and with a minimum of human interaction. Symons estimated there were 83 cases of poisoning in her stories (at least partly inspired by Christie’s time working in a pharmacy during World War I). As another recent Christie biographer, Laura Thompson, observed, what fascinated Christie was “the gleaming neatness of the bottles, the elegant precision of the calculations, the potential for mayhem contained and controlled.”

While the years after her divorce were emotionally tumultuous, they were also some of her most productive—a time when she wrote many of her best books, such as Peril at End House (1932), the first two (and two best) Miss Marples, Murder at the Vicarage (1930) and The Moving Finger (1942), the twice-filmed Murder on the Orient Express, and the many-times-filmed and adapted And Then There Were None (1939). As decades of her well-kept notebooks attest, Christie enjoyed plotting novels even more than she did writing them; and each contraption of plot seems designed to lead readers into a story, show them multiple false exits, and then snap shut all the doors before they get any bright ideas about finding a way out for themselves.

Christie wrote her most emotionless and divertingly complicated stories when she was at her most vulnerable. But at other times, under the name Mary Westmacott, she let those emotions loose—and Westmacott novels such as Unfinished Portrait (1934) and The Rose and the Yew Tree (1948) provide better emotional insight into Christie—which could get pretty turgid. Eventually, after her successful second marriage to the archaeologist Max Mallowan, whom she met while touring his dig in Iraq, she grew increasingly secure and prosperous. And it was possibly no surprise that a woman who spent her life trying to reclaim the homely securities of the past would prefer the company of archaeologists. In fact, she spent so much time on digs (while partly subsidizing them), that she had her own mobile toilet built, which was referred to as “Agatha” at the British School in Baghdad until several years after her death, when it was infested by termites and burned.

For a body of work so vastly populated with dead bodies, the Christie oeuvre may ironically be the most peaceful, predictable, comforting space in twentieth-century literature. The stories rarely (if ever) refer to our ugly political world; the simplistic psychology of the characters is easily dissolved by either love or money; and each novel takes place in a timeless space lacking any actual historical or cultural landmarks, such as market crashes, wars, death camps, crime families, corrupt politicians, or pandemics. And at the end of each story, after the victory of wits is won by a slightly-more-brilliant-than-the-murderer detective, the murderer is clearly identified and eliminated—usually by a hangman’s noose, or by their discreetly removing themselves offstage, where they commit suicide. For they are easily the most obliging and polite murderers in crime fiction.

In Christie’s universe, the most sensible and ubiquitous human motive is, as Poirot often exclaims, the “inevitable motive. Money, my friend, money!” Even when a murderer appears to be insane, for instance, in The ABC Murderers (1936), where it first appears that a murderer roams the country randomly identifying victims by the first letters of their last names, Christie’s murderers are always eminently logical and almost pathologically “reasonable.” Only fools (such as Poirot’s recurring foil, the much dumber Captain Arthur Hastings) attribute madness to a murderer, for the real problem with most murderers, Christie’s detectives repeatedly argue, is not their capacity to commit violence, since virtually “everyone is a potential murderer,” but their capacity to devise complicated schemes for avoiding capture. They are more reasonable and judicious than everybody else, and that’s what makes them dangerous.

If criminals murdered out of passion or rage (which they rarely do in Christie), they might well get away with it. But by cleverly “trying to cover up their tracks, they invariably betray themselves.” Unlike American thrillers, Christie’s stories don’t devolve into escalating mayhem and violence until the streets are littered with corpses (as in Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest); rather, they present stories in which individual acts of violence can be resolved and contained. Christie’s murderers kill to beat the social order at its own game; they seek to be more successful than everybody else. But the act of murder is also an opportunity for the social order to reestablish itself by evicting (or eliminating) the culprit. “Out of confusion comes order,” Poirot tells Hastings. Every crime in the Christie canon is an opportunity to make the world safe once again.

The “solving” of each (often absurdly) complicated murder is never quite so important to Christie (or her amiable, cantankerous, and often elderly detectives) as elaborating how many local suspects are capable of committing the murder and possess good reasons for doing so.

Her small, local, middle-class white communities are rife with suspicion, infidelity, unease, and a sort of indefinable evil that permeates almost everybody and everything. At the opening of The Moving Finger, the local vicar wakes up to an anonymous letter accusing him of being his sister’s lover—and similar letters, filled with disturbing accusations, are sent to other members of the community, eventually weaving them together in a “trail of blood and violence and suspicion and fear,” which describes the most common atmosphere in a Christie novel.

Miss Marple, Christie’s greatest creation, isn’t a paid detective like Poirot; she’s an irrepressible snoop, always checking out neighbors with her opera glasses, keeping notes of their whereabouts at different times of the day, collating the latest gossip and aspersions, and sending instructions to the local police about what questions they should ask of whom. In Finger, she operates almost as invisibly as the murderer, rarely at the center of scenes so much as orbiting at their periphery, dropping notes off to various locals, passing on information and opinions through third parties, and never getting too closely involved with her neighbors—which seems to be her personal strategy about surviving village life. In The Body in the Library (1942), one friend refers to her “low opinion of human nature” as “refreshing,” especially at a time when people often had “too much of the other thing.” (“One does see so much evil in a village,” Miss Marple later reflects.) And Poirot often feels that most murder cases share one similar characteristic: “Everyone concerned in them has something to hide.”

People are either lying about their relationships to one another or their true identities, or their relationships to the victim, or how much (or how little) they were implicated in unsolved crimes of the past. In Orient Express, (spoiler alert to anybody who may have been living on the moon for the past 50 years), all the chief suspects turn out to be a corporate murderer of the same man; and in And Then There Were None (same spoiler alert), every one of the victims has committed some crime in the past for which they are (deservedly) punished. One of the hardest parts of reading a Christie novel is keeping the characters straight—since they are all, to some degree, at least mildly unsavory, dishonest, and guilty of something. They are also mostly white, attractive, well employed, and well dressed; and they all speak with the same polite middle-class manner—however, as in Poirot’s case, distinctly accented. Their characters (if they can be said to possess characters at all) are entirely distinguished by incidental qualities: jobs, interests, sexual attractions, and family histories. (At one point, Pocket Books wisely included a “Cast of Characters” at the beginning of each novel just so you could keep track of the names of the hotel owner, the butler, the dowager’s second son, and so forth.)

This is the second “major” biography of Christie in 15 years, and while it’s an enjoyable opportunity to reconsider the immersive, bathtub-like pleasures of Christie’s work, it’s hard to see what more it offers than the previous one by Laura Thompson in 2007. Certainly, Worsley doesn’t do as extensive a job of closely reading through the breadth of Christie’s work, or of measuring Christie’s strengths (fast scenes and dialogue, all-absorbing clue-fests, and enough surprising plot traps to capture even the wariest readers) against her manifold weaknesses (too much of all the above). And like previous biographers, Worsley spends an inordinate amount of time on Christie’s now legendary 11-day disappearance, perhaps tempted by a century-long question regarding Christie’s life: Can the motives of her disappearance be solved as satisfactorily as in one of her novels? The short answer is probably no, for the greatest “mystery” of Christie’s life may simply be that her 11-day fugue was little more than a frantic elopement from reality conducted by a desperately unhappy woman.

Christie’s place in twentieth-century literature is both irrefutable and endlessly disputed; and even if she may have lost the “Battle of the Brows,” as Evelyn Waugh once put it, it’s still hard to meet anybody who has never enjoyed a Christie novel and/or one of the multitudinous movie and TV adaptations. And while Edmund Wilson once famously asked, “Who cares who killed Roger Ackroyd?” Christie’s multitudinous fans over the past hundred years might fairly respond: “Who the hell is Edmund Wilson?” Christie’s novels have been acclaimed by many of her fellow practitioners, including Dorothy Sayers and Julian Symons, and just as heartily condemned by others, such as the late, great Michael Dibdin, who once said of her:

Her aim was to fool the readers, and she sacrificed everything to achieve it. The plots in Christie’s novels were all basically the same—an ill-assortment of people gathered at an out-of-the-way place where a murder takes place. The characters were all generalised types. There were never any complex psychological characters. They were devoid of any emotional depth. Her books were artificially pure, and she ignored the problems faced by society.

She “was a killer,” concluded Dibdin (who himself brought the unsolvable world of political corruption roaring into his chaotic and absorbing Aurelio Zen novels), “and her victim was the British crime novel.”

Christie’s weaknesses are manifest: Her humor is mild at best; there are undercurrents of racism, especially against Jews (in The Secret of Chimneys, she describes a Jewish businessman, Mr Herman Isaacstein, as having “a fat yellow face, and black eyes, as impenetrable as those of a cobra”); her late-career slump lasted decades; and her detectives—with the possible exception of Miss Marple—are among the least interesting and most irritatingly repetitive in mystery fiction. And yet it is hard to read two or three of her best novels without experiencing a small, sweet thrill of purely escapist pleasure. As successfully as Tolkien or Lewis, she devised an all-encompassing alternate world—one in which nobody commits a crime without eventually paying for it. (Ha.) There are even some novels, such as Curtain—the “last case” of Poirot, written in the 1940s and locked away in a security box until its publication in 1975—that may still surprise and delight the most experienced whodunit lovers.

But like many British subjects of her time and class, Christie viewed change with suspicion. And in her later years, she continued producing the same sorts of novels so often that even many of her biggest fans began to grow weary. (There is a point during the final 40 pages of most Christie novels where you just want to identify whether it was Colonel Mustard or Mrs. Peacock with the butter knife and go to bed.) And in one of her last and bestselling novels, Passenger to Frankfurt (1970), Christie’s apartness from the world never felt more extreme. In one of her few “political thrillers,” Hitler survives the war by hiding out in an asylum, while his Nazi confederates feverishly sow drugs, discontent, and even worse—promiscuity!—in all those places where things change too much for someone like Christie: the youthful college campuses that she rarely visited.

It may have been the silliest irony of her life that while she could plot puzzles for readers like nobody’s business, she couldn’t solve this almost too obvious puzzle of the 1970s: Why would college kids rebel against a society being run by privileged, cloistered middle-class individuals like those in Agatha Christie’s novels? As long as she lived, she never came close to solving that one.