In the mid-1860s, Russia was in the throes of a true crime craze. Among Czar Alexander II’s sweeping reforms—including, most notably, the abolition of serfdom—were overhauls to the criminal justice system and greater freedom of the press. The introduction of a jury system and the opening of courts to the public turned criminal trials into a new kind of theater, and newspapers—suddenly abundant—were keen to commentate on the show. Russians curious about how justice would be meted out in this new era bought papers like Glasnyi Sud (Open Court) and read court stenographers’ reports as if they were lines from a play. Sections like “The Criminal Chronicle” became a regular feature of daily newspapers, introducing new social types like the charismatic defense attorney. One publisher went so far as to say that trials were “superior to novels” in offering insight into human nature. The reading public would not have to choose; detective fiction and the crime novel were quick to emerge out of the swirl of grisly reporting. In the 1860s, to turn the pages of a periodical in Russia meant you were likely to get blood on your hands.

Few people consumed these stories more voraciously than novelist (and ex-convict) Fyodor Dostoevsky. In September 1865, he was staying in the German spa town and gambling resort of Wiesbaden, where he lost nearly all his money at the roulette wheel. He could not pay his hotel bill, and the dining staff had been instructed to stop bringing him dinner. To keep hunger at bay, Dostoevsky decided he would limit the amount of physical energy he exerted. One day, stationary in his room, he read the story of a man who murdered a cook and a washerwoman by bludgeoning them to death with an ax. The newspaper said he was a raskolnik, a schismatic who had rejected Western reforms of the Russian Orthodox Church. Not long afterward, Dostoevsky sent a note to his editor in Saint Petersburg, Mikhail Katkov, telling him he had an idea for a story:

A young man, expelled from the university, petit-bourgeois by social origin, and living in extreme poverty, after yielding to certain strange, “unfinished” ideas floating in the air, has resolved, out of lightmindedness and of the instability of his ideas, to get out of his foul situation at one go. He has resolved to murder an old woman, a titular counselor who lends money at interest.

That young man—a university student who intellectualizes his egoism with the aid of “unfinished ideas” (Western concepts that the nationalist Dostoevsky did not like)—would be given the name Raskolnikov, and what Dostoevsky first conceived as a 90-page story would eventually sprawl into an entire novel that is set in motion by a pawnbroker and her sister having their skulls cracked open with an ax. The specifics of the contract could be worked out later, Dostoevsky told his editor. For now, he needed 300 rubles immediately to pay the hotel.

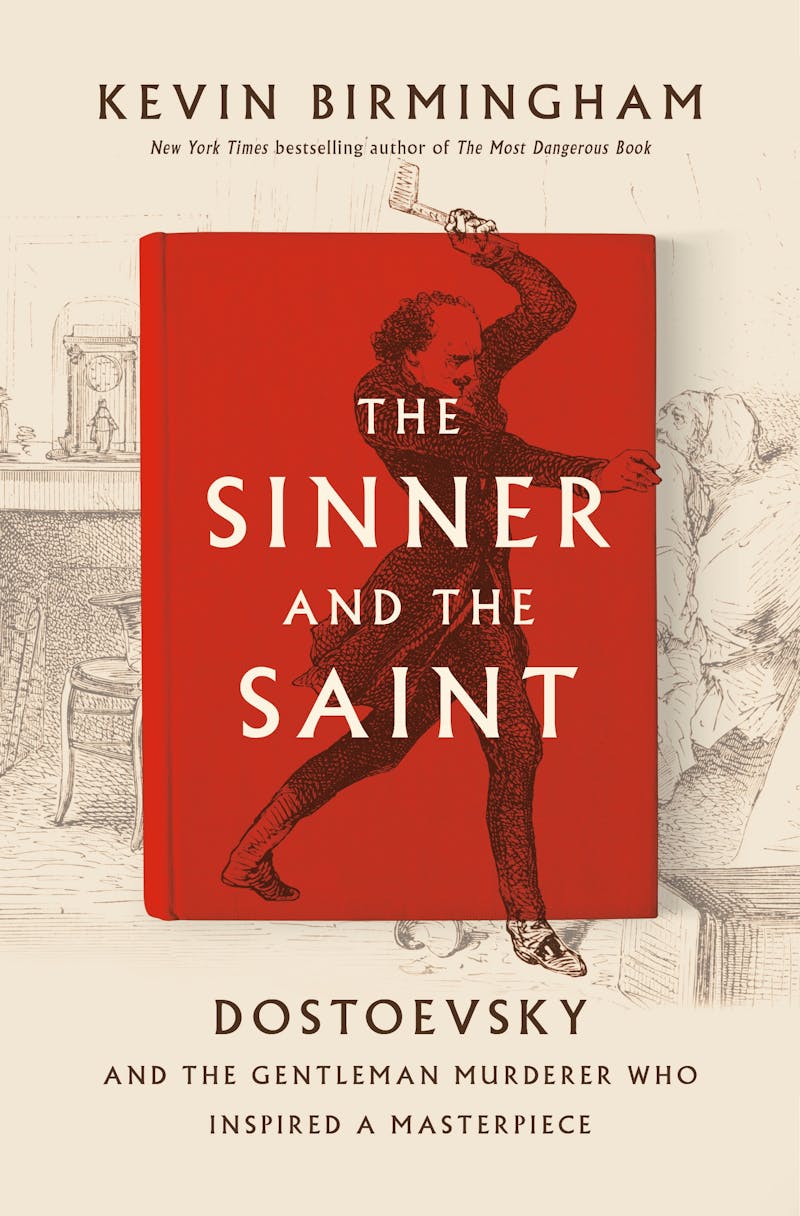

The religiously devout ax murderer that Dostoevsky read about is not the main subject of Kevin Birmingham’s The Sinner and the Saint: Dostoevsky and the Gentleman Murderer Who Inspired a Masterpiece. That would be Pierre-François Lacenaire, a poet and serial killer whose 1835 trial had been extensively covered in the French press and captivated the likes of Balzac and Stendhal. Lacenaire was handsome (throngs of women crowded the public gallery in the courtroom), an intellectual (he read Rousseau as he lay in wait for his victim), and not only declined to show remorse but professed an open disdain for morality itself. He was indifferent to his own depravity, and it was electrifying. “I love to see men like that,” Flaubert said of him, “like Nero, like the Marquis de Sade.”

As he unspools the story of how Dostoevsky first encountered the villain Lacenaire, Birmingham places the author in a culture brimming with tales of criminal intrigue and moral transgression—some Dostoevsky had gathered from his time in a Siberian prison, but many he came across as a voracious consumer of what we might now call true crime. As such, Birmingham’s book reads mostly as a biography of Dostoevsky from his youth through the writing of the novel, one that traces how the author’s views on crime were forged between his time in prison for insurrection and his eventual release into a new literary scene that was—by his estimation—dangerously aestheticizing the kinds of criminals he had seen up close and in the mirror.

Crime sold. A dead body, sexual impropriety—or ideally both—moved papers. That Dostoevsky’s editor commissioned Crime and Punishment on the strength of such an opaque proposal was no doubt partly driven by the fact that readers were rabid for all things crime: “The first wave of Russian crime writing was cresting,” Birmingham writes, and “the public was hungry for tales of lurid offenses.” Dostoevsky assured Katkov that the plot “is not at all eccentric,” pointing to recent cases in a similar vein. “He informed Katkov,” notes Birmingham, “that he had heard about an expelled Moscow University student who resolved to kill a postman” and mentioned other criminals he had read about in newspapers, like “that seminarian who murdered the girl in the shed … and so on.”

In fact, just before the first chapters of Crime and Punishment were to be published, newspapers began to report details of a strikingly similar murder case. In Moscow, Birmingham recounts, “a law student named Danilov murdered a pawnbroker in his apartment.… As he was ransacking the place, the pawnbroker’s servant unexpectedly arrived, so he murdered her, too.” In the novel, Dostoevsky places Raskolnikov, both as a writer and reader, into the media landscape of the era. The detective on the case questions him about an article, titled “On Crime,” that he had published in a student journal months before the murder. In it, Raskolnikov argues that there are certain men—great ones—who exist above morality and for whom the act of murder should be sanctioned. Elsewhere in the novel, Dostoevsky has Raskolnikov rush into a tavern looking for a copy of the most recent newspaper, excited to read about his handiwork in the crime pages. But it takes him some time to finally find the story. The criminal world of Saint Petersburg had been busy that week, it turns out.

Even amid a glut of gory tales, the Lacenaire spectacle stood out for Dostoevsky. He first heard the name Lacenaire in 1861, while looking for crime stories to use in the literary journal he published, Time. Leafing through a French collection of criminal profiles, he saw an illustration of Lacenaire’s infamous double murder of a mother and son. In the picture, the finely dressed Lacenaire brandishes an ice pick at the old woman, shown, Birmingham describes, “cowering in her bedclothes, looking up, eyes wide.” The next year, Dostoevsky encountered Lacenaire again, this time in the pages of Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, Les Misérables—which mentions Lacenaire by name (and many felt the character Montparnasse was no doubt inspired by the genteel killer). Dostoevsky started developing plans to write an article “about instincts and Lacenaire,” but never finished. Lacenaire, with his inchoate, vaguely republican politics—which seemed to exist as a kind of ex post facto justification for his crimes—was a type Dostoevsky believed to be emerging among Russia’s youth: the student terrorist.

The outlines of modern-day terrorism—small, isolated cells of insurgents using violence as propaganda—are said to have emerged in Russia in the 1860s. By the end of the century, terrorism was referred to by those throughout the world—including Karl Marx—simply as “the Russian method.” Universities had been locus points in radical organizing; among the disaffected youth were some who believed the reforms of Alexander II did little to stem poverty and rampant social inequality, and that the country had to be shocked into change. What was needed, they believed, was “a bloody and pitiless revolution, a revolution which must change everything down to the very roots,” declared a pamphlet that landed on Dostoevsky’s doorstep. Many were inspired by a writer and journal editor, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, whose 1863 novel, What Is to Be Done?, was regarded as a kind of bible by its radical adherents. The novel glamorized the lives of self-sacrificing revolutionaries, whose readiness to accept martyrdom made them romantic heroes. Such a blueprint had also been set, notes Birmingham, by Dmitri Karakozov, a university student from a poor provincial family who in 1866 fired a gun at Alexander II as he strolled through the Summer Garden in Saint Petersburg. The attempted assassination of a czar, the first such attack in Russia, may have failed, but—more importantly—the story made the papers. Karakozov wanted, Birmingham explains, “to reset all of Russia’s political machinery with one jarring act of violence and a manifesto amplified by the mass media.”

The power of the press to create celebrities out of criminals was not lost on Dostoevsky, and indeed it figures in Raskolnikov’s psychology after the murder. Political criminals, whose transgressions had the potential to reorder the foundations of society, would become a major subject in Dostoevsky’s later fiction, namely in his novel The Possessed (1872), in which he would try to expose, as he had in Crime and Punishment, what he believed were the misguided and egotistical motivations undergirding the new radicalism.

Was he speaking from experience? Dostoevsky had been arrested in 1849 for his participation in an underground salon whose members read banned works and discussed French Utopian socialism. He had spent the next four years in prison, where he had undergone a political conversion, abandoning the radicalism of his youth to become, on many issues, a conservative. Yet, what incensed Dostoevsky above all about Chernyshevsky was his blind faith in scientific explanations for human behavior. Chernyshevsky became known for a theory he called rational egoism. Inspired by Jeremy Bentham and English Utilitarianism, Chernyshevsky claimed that human behavior was rational in that it was guided by self-interest. If poverty were to be eliminated, he conjectured, crime would all but cease to exist.

Dostoevsky had served side by side with murderers in prison, “sharing tables and latrines with them, hauling bricks with them, sipping water from the same ladles,” writes Birmingham, and could not abide this simplistic view of crime—and by extension of human nature. People were unpredictable, irrational, and often did things that worked against their own interests—this was ugly, but also beautiful, because it was the essence of freedom. Indeed, this is why Crime and Punishment became a crime novel in which the whodunit is answered straight away, leaving the rest of the novel for questions of motive or—more accurately in the case of Dostoevsky—the muddled mess that is human motivation in the first place.

The Lacenaire case was the perfect foil to Chernyshevsky’s theory, because his crimes defied any logical explanation. Spectators were at a loss to understand what propelled a well brought up and highly intelligent young man to stab an elderly woman in the face while his accomplice slit her son’s skull open with an ax. The immediate motive was money, of course. “But that,” writes Birmingham, “did not explain his ruthless indifference, or why he intended to kill people when robbery would suffice.” Lacenaire gave a number of explanations, which just introduced more inconsistency. He claimed to be overcome by “a fixed idea to resist,” but in his memoirs (which were published ahead of his execution) he wrote: “I come to preach the religion of fear to the rich for the religion of love has no power over their hearts.”

The French press seized on the political undercurrents in Lacenaire’s pronouncements. His distaste for authority and for the ruling classes was used to dredge up fear over revolutionary elements in French society. “If one could kill a king for one’s country, then why not kill a banker?” as Birmingham sums up the rhetoric: “Lacenaire’s crime spree was captivating because it seemed to be the revolution’s next rational step.” This was a reach. In attributing Lacenaire’s crimes to politics, the press was imposing an uncomplicated narrative on what Dostoevsky would have recognized as the chaos of human ego and the mysteriousness of our actions.

In Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky used the public’s appetite for crime stories as a kind of Trojan horse, a way to launch a polemic under the guise of titillation. Dostoevsky denies Raskolnikov the glamour of a martyr and presents him instead as an angry and confused young man, humiliated by poverty and acting out of shame. Or at least that is what he thought he had done. In something of a plot twist, following the success of Crime and Punishment, defense attorneys in nineteenth-century Russia began comparing their clients to Raskolnikov in an attempt to garner sympathy with the jury.

Raskolnikov and his crimes continue to bleed into real life. Once, during a study abroad trip in Saint Petersburg, my teacher encouraged me to go on the Crime and Punishment walking tour. One of the attractions, she explained, was the apartment building where Raskolnikov kills the pawnbroker. It was and is a very popular tour, but I was confused—“none of this actually happened,” I thought. I went and got lunch instead.

I have never quite gravitated to books promising to uncover the “true stories” that inspired great works of fiction. If anything, I am more fascinated by moments when fiction starts to infect reality, when characters we read about on the page start to shape what we expect out of one another off it. I think Birmingham would agree. Lacenaire makes up far less of his narrative than one might expect. Instead, he shows us that Dostoevsky is both the “sinner” and the “saint,” a repentant political criminal who wanted his characters to inspire not fervor but fear—of our worst instincts.