Cultural consensus is a tricky thing. Broad shifts in sensibility, taste, and topical relevance can make an artist seem to speak singularly to a historical moment—and just as rapidly, this tacit social contract can be dramatically overhauled, or jettisoned altogether. Johnny Cash, the great baritone country music Everyman, weathered virtually all these reputational swings across his long career, ending up as an elder prophet of the Americana movement, thanks to his last musical legacy: the spare and gothic “American Recordings” series produced by Rick Rubin in the 1990s.

Still, in a contemporary cultural landscape that’s acutely short on consensus, in both the expressive and political realms, it’s tempting to look back on a figure like Cash as an avatar of a bygone era of comity and understanding—a speaker of hard truths to an engaged American mass audience in desperate need of trustworthy voices and reliable moral authority. When Cash took up the causes of Native Americans, veterans, and prisoners, he undeniably leveraged the bully pulpit of mass celebrity to champion the interests of forgotten, neglected, and abused Americans. And like his great songwriting contemporary Dolly Parton—whose odyssey into social-justice-minded entertainment was chronicled in Sarah Smarsh’s 2020 book She Come by It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs—Cash greatly complicates the popcult caricature of country music as a univocal genre of jingoist belligerence and boosterism, as exemplified by Toby Keith, Daryl Worley, Hank Williams Jr., and the late-career Charlie Daniels.

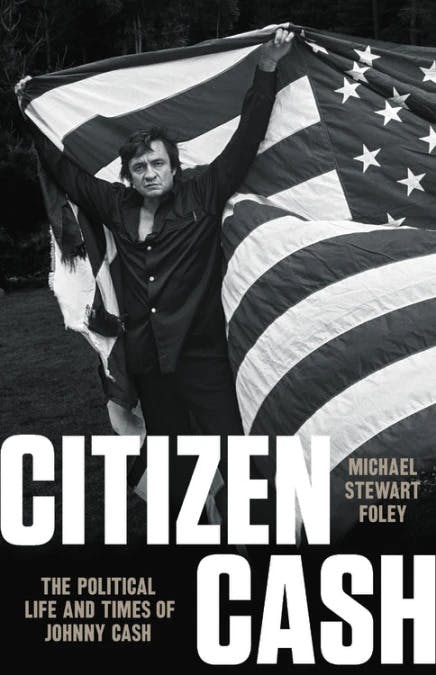

In his book Citizen Cash, however, historian Michael Stewart Foley sees Johnny Cash as something much more than a country songster with a social conscience—he was, in fact, “one of America’s foremost public citizens” and a champion of “a new model of public citizenship based on empathy.” To the record-buying public, “Cash seemed as permanent in American life as the Lincoln Memorial,” but unlike the stately monuments of past guardians of our civic traditions, Cash embodied a rough-hewn, experiential ideal of American belonging that “was fundamentally democratic and inclusive.” Foley notes that Cash “never trafficked in grievance” and, unlike the apostles of today’s resentment-fueled right, attempted to establish “a kind of solidarity” with listeners whose experiences he could not share.

“Cash’s empathy,” Foley proposes, “transcended ideology—it was supra-partisan.” It’s an appealing argument for the hymning of bygone communions of daring artists and mass audiences. Unfortunately, it’s not really borne out by the facts of Cash’s life.

Foley’s effort to force Cash’s life and artistic career into the procrustean bed of empathic politicking tends ironically to flatten out the legacy of Cash himself; at virtually every juncture of Citizen Cash, he translates the singer’s creative and commercial exploits into stages in his progression toward maximum empathy. Born in 1932, Cash came of age in the poor farming community of Dyess, Arkansas—a New Deal agricultural settlement that sought to break the stranglehold of sharecropping in the region with small independent farms, knitted together into cooperatives of crop distribution and marketing. For all the Roosevelt administration’s ambitions, however, Dyess remained mired in rural poverty, and Cash frequently recounted the travails of neighboring sharecroppers, both Black and white.

The trajectory of Cash’s childhood and early career—the tragic death of his older brother Jack, his European tour in the Air Force during the Korean War, his determination to break into the record industry as a young newlywed in Memphis, his struggles with drug addiction, and his dogged courtship of his eventual second wife, June Carter—is now familiar pop culture lore. Indeed, the story is so familiar that it propelled not only the plot of the celebrated and Oscar-winning 2005 biopic of Cash, Walk the Line, but also a satirical send-up, the 2007 John C. Reilly vehicle Walk Hard.

For Foley, however, the Behind the Music–style saga of Cash’s commercial rise and personal struggles is but the backdrop to the artist’s coming of age as a full-blown social prophet. When Cash released Songs of Our Soil in 1959,* Foley sees him following “in the footsteps of no less than Walt Whitman.” He quotes, from Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” the lines “I do not ask how the wounded person feels / I myself become the wounded person / My hurt turns livid on me as I lean on a cane and observe.” Across Cash’s career, Foley remarks, his “empathy for his subjects found him, more often than not, observing closely the hardship of others and becoming ‘the wounded person’ on his records.”

Unfortunately, Cash’s ascension toward Whitman’s Democratic Vistas was abruptly derailed in Cash’s next Columbia album. 1960’s Ride This Train featured a Tex Ritter tune called “Boss Jack,” which narrated, in cringe-inducing language and imagery, a slave songwriter’s devotion to his paternalist white master. Foley correctly notes that this song choice—which appeared at an especially fraught and violent phase of the white backlash to civil rights protests in the South—was both morally indefensible and out of step with the halting progress toward social democracy in the United States. But he writes the choice off as a regrettable lapse steeped in the misguided politics of complacent white “moderation” that prevailed in the country music capital of Nashville, where Cash recorded Ride This Train. However, Cash was no son of Nashville—in Dyess’s model agricultural community, Black farmers were denied access to the federally financed homes and lots in the project. During Cash’s Air Force tour, Foley also notes, he had bragged about beating up Black soldiers and freely used the N-word and other slurs to deride them and their manhood. At least in the early phase of his recording career, Cash came by his racist attitudes the way that most white Southerners did—as a de facto racial and regional birthright, shored up with generous subventions from the American political economy.

None of this is to brand Cash an incorrigible lifelong racist; as Foley notes, Blood, Sweat and Tears, the next entrant in Cash’s Columbia discography, was strongly influenced by Alan Lomax’s 1930s field recordings of Black work and prison songs, Blues in the Mississippi Night, and was surprisingly frank in its depictions of routine racial brutality for a country record of the time. However, Foley’s not an interpreter content to salute this work as a provisional breakthrough registering a long-overdue reckoning with the unresolved legacies of slavery and Jim Crow on the part of a white Southern artist. No, by his lights, Blood, Sweat and Tears “is the one great record made in support of Black lives by a country music star”—even though, as he’s also obliged to note, “almost everyone missed its message” when it was released.

This rushed-though-massive disclaimer points up another gaping difficulty with the argument of Citizen Cash: If Johnny Cash is a performer imprinted like the Lincoln Memorial on the consciousness of the American public, wouldn’t a Cash-produced anti-racist broadside have made an impression as such on his audience? Instead, to keep his outsize claim for the record’s topical impact looking viable, Foley continues to pile disclaimer upon disclaimer. “The significance of Blood, Sweat and Tears escaped the segregationists,” he observes—something that, again, seems to mark a concept album devoted to the injustices of race in the 1960s as something of a misfire. Then again, the significance of the album appears to have eluded Cash in no small part, as well: While he continued performing some of the record’s race-inflected material in concert, Foley writes, Cash “said nothing publicly as the clashes between civil rights activists and racists in the South intensified in 1963, 1964, and 1965. In these years of the March on Washington, Freedom Summer, and the Selma to Montgomery March, Cash did nothing more to provoke the segregationists”—a particularly baffling claim, since Foley had already stipulated that the segregationists weren’t really provoked by Blood, Sweat and Tears in the first place.

Not surprisingly, when Cash lapsed into moments of racial reaction in his later career—confessing on his primetime network variety show that he identified with the Confederate cause in the Civil War, and responding with an outraged letter when a group of segregationists alleged, on the basis of a blurry wire service photo, that his first wife, Vivian, was Black—Foley is duly armed with extenuating explanations. The first instance, he takes care to point out, occurred during a monologue segment in which Cash “was signaling his skepticism over the Vietnam War,” and the latter “seemed less like a principled stand than an isolated incident.”

All this suggests that there’s not a great deal of actual politics in what Foley calls Cash’s “politics of empathy.” Any politics worthy of the name would seem to impose a sense of obligation to a shared goal beyond the fallback preferences of the self, but Foley’s dissection of Cash’s social commitments effectively inverts this logic. Cash “rarely took ‘stands’ on issues in conventional ways,” Foley writes. “Instead, he approached each issue based on feeling.” He then goes on to cite a performance on Cash’s TV show, filmed in Nashville’s famed Ryman Auditorium, centering on a song Cash had adapted from Blues in the Mississippi Night called Another Man Done Gone, which relates the brutal killing of a captured fugitive from a chain gang. As the song builds to its conclusion, Cash delivers the grim aside that “it’s almost enough to make a man give a damn.” Foley, not surprisingly, hails this as a landmark moment in Cash’s—and by extension, the nation’s—social consciousness. (Once more, however, Foley is forced to stipulate in nearly the same breath that the song in question has been historically whitewashed; the version that Lomax recorded gruesomely depicted the fugitive’s lynching to punctuate the racial horror of the episode, and Cash’s adaptation excised that crucial passage. But never mind: “Although Cash did not explicitly mention race, the audience at Ryman knew the score.”) Cash “may as well have played prosecutor,” Foley exults, “and brought up everyone who tuned in that night on charges of First Degree Apathy and Accessory to Murder After the Fact.”

Again, there’s no question that Cash did great work by bringing penal abuse—the subject that would be the main social preoccupation of his later career—to the attention of his TV audience and the crowd at Ryman. And Cash’s own views on race had thankfully evolved beyond the casual white supremacy of material such as “Boss Jack.” But Cash’s prosecution here seems deliberately calculated to leave the defendant with generous grounds for future appeal. For starters, it’s simply not the case that Cash’s fans at Ryman—let alone the vast national network viewing audience—would “know the score” in interpreting the events narrated in “Another Man Done Gone” as a racial lynching. Much of the history of modern country music, after all, involves the incorporation of Black forms of expression into a white-dominated genre, going back to storied country innovators such as Jimmy Rodgers, Bob Wills, and Hank Williams. Much of the commercial success of country has relied on audiences not knowing the score when it comes to race.

One could still, of course, argue that Cash had edited out the racially charged verse in “Another Man Done Gone” on grounds of commercial taste, or in deference to the standards and practices canons of network TV at the time. But if that were the case, he had a wealth of other material at his disposal to make a powerful statement about race, if that’s what he intended to do, from Bob Dylan’s protest catalog (which Cash ardently admired) to an even deeper tributary of African American ballads in the vein of the uncensored version of “Another Man Done Gone.” So Foley’s readers are left pondering Cash’s distinctly muffled indictment of white racial power alongside the other episodes in his career bespeaking an erratic commitment to principles of racial justice—and suspecting that his audience was likewise apt to shun the specter of racial discomfort whenever it was afforded the opportunity.

And this, in turn, is the larger problem with looking for a politics of empathy and feeling: It’s the nature of feelings that they change. Sometimes, as in Cash’s later career, these changes produce an enlarged moral imagination and a more inclusive conception of the common good. At other times, though, the pendulum swings toward far more ugly extremes, and the politics of reaction and retrenchment become charged with an ominous irrational appeal, which is now very much the mood in the Trumpier reaches of country music, and in America at large.

Again, none of this is to downplay Cash’s admirable example of engaged songwriting artistry and celebrity—and Foley’s argument is on far stronger grounds when it recounts Cash’s strong commitments to the causes of veterans’ rights, prison reform, and Native American justice. But the case for recasting Cash as a poet-statesman on the vanguard of democratic self-expression is ultimately both too sweeping and too confining to match up with the legacy of the actually existing Johnny Cash. Cash’s life and work make for enormously rich and rewarding study without the added burden of anointing him an unheralded savior of America’s battered civitas—it was far more than enough that he was Johnny Cash.

* An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Songs of Our Soil was Johnny Cash’s first major label L.P.