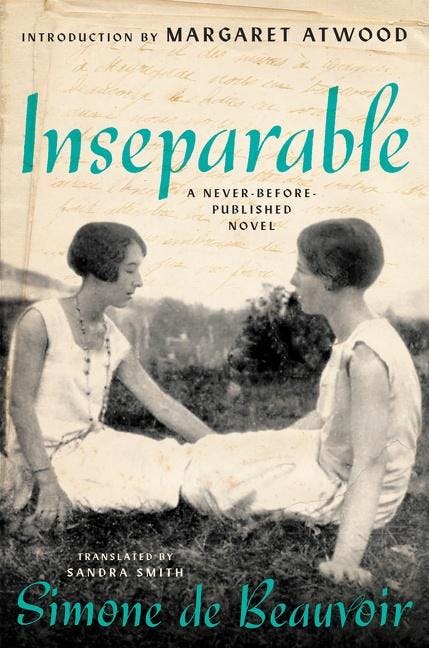

There is a photograph of Simone de Beauvoir with her best friend Zaza, taken on a warm day in September 1928. They are 20, between girlhood and womanhood. They have matching haircuts, short dark bobs announcing them as modern. Bare arms emerge from loose white dresses, tanned in Zaza’s case, paler in Simone’s. Clothed knees touch, giving the impression they are one person, a twin-headed mermaid in dialogue with herself. These are women captured in the act of thinking, a decade into a conversation begun as children and becoming more dangerous as the pressures of the world become more painful. Their fingers grip the grass, playing with it or wrenching it as they grapple with the question of how to live. A year later, Zaza will be dead.

This moment, when a girl becomes a woman, would be crucial to Beauvoir’s fiction and philosophy, and her friendship with the exuberant, tragically-fated Zaza would be a touchstone for the next thirty years. The two met at Catholic school in high bourgeois Paris, when they were nine years old. Zaza was intelligent, irreverent, an ardent violin player and a great mimic, disobedient at school but conventional at home, passionately devout. The girls became inseparable and Simone realized that she was miserable in Zaza’s absence and that this friendship was quickening into love. She didn’t reveal her feelings.

The expectations placed on both girls were frighteningly conventional, but Simone’s father was finding ever more feckless ways to lose money. The fact that she would have no dowry as a result gave her a form of freedom: Unable to marry well, she would make her own living through teaching and writing. The opposite was true of Zaza, who had a vast dowry. As she approached marriageable age, the freedoms of girlhood narrowed to an endless round of tea and tennis parties. When she fell in love with Simone’s brilliant, aloof friend Maurice Merleau-Ponty, her parents said they could stay together if they got instantly engaged. Merleau-Ponty refused on rather weak grounds and Zaza, overwrought and unhappy, got ill with the viral encephalitis that would kill her. Had she died of a broken heart?

It’s a peculiar, pointlessly tragic story that for the devastated Beauvoir was a fable for her times, showing how little freedom was available to women. Peculiarly, Beauvoir, whose life expanded as rapidly as Zaza’s had narrowed, said, “I had paid for my own freedom with her death.” By her twenties, Beauvoir had renounced her faith, but was still superstitious enough to feel that Zaza’s death was hers to atone for.

Zaza continued to matter deeply to her even as she made her famous pact with Sartre, took on a coterie of male and female lovers, collaborated with Sartre on the notion of “bad faith” and cajoled him into adding ethics to existentialism. In 1954, she wrote a novel about her friendship with Zaza, but never published it. Translated by Sandra Smith and titled Inseparable, the book has been published for the first time this year, and shows her thinking through the experiences of adolescence with particular intensity, trying out an alternative, more rapturously emotional vision of herself as a novelist.

In the years before she wrote the novel, Beauvoir had been thinking about Zaza in her work. Arguably, Beauvoir’s gargantuan achievement in The Second Sex (1949)—turning womanhood into a question that needed thinking through—was fueled by this peculiar, unsatisfactory story from her childhood. We can feel Zaza shimmering through the pages of the book. Its section on childhood recalls Zaza’s experience, more than that of the young Simone. “Up to twelve, the girl is just as sturdy as her brothers; she shows the same intellectual aptitudes,” Beauvoir writes. After that, she is treated as a living doll, denied the freedom to understand the world, prevented from affirming herself as a subject. It’s not surprising that George Eliot had to kill Maggie Tulliver, her passionate, independent heroine, she observes. “The girl is touching because she rises up against the world, weak and alone; but the world is too powerful; she persists in refusing it, she is broken.”

This girl, broken by the world, continued to preoccupy Beauvoir, even after she had theorized her predicament in The Second Sex, turning character into archetype and then going on to propose alternative ways of being a girl and becoming a woman. Next she wrote her magisterial novel The Mandarins, which would win the Prix Goncourt in 1954. Straight afterwards, she found herself drawn back to that long-past episode with the “touching” girl, writing Inseparable. She would then go on to write of it once more (and publish it) in the first volume of her memoirs, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter.

Why, at the height of her ambition, did she choose to write in the comparatively slight form of Inseparable? She’d helped Sartre redefine the novel form with Nausea, she’d pioneered a new novelistic form of her own with The Mandarins, one capacious enough to include the largest political questions. Together—along with so many other of their philosopher-novelist contemporaries (Albert Camus, Georges Bataille, Maurice Blanchot—all male!)—she and Sartre were bringing together the world of modernist experiment with an emancipatory modern agenda and with the new philosophical mode, inspired by Heidegger, that had made everyday life a rich source of philosophical enquiry. Now she wrote a short novel in the first person narrated by a directly autobiographically inspired heroine and telling the story of her youthful friendship chronologically. She’d just begun a relationship with the filmmaker Claude Lanzmann, and, bothered by his being 16 years younger than her (she was preoccupied with aging in The Mandarins), she may have wanted to revive a younger version of herself through writing.

The narrator, Sylvie, tells of her friendship with a girl named Andrée, who arrives at school at the age of nine having spent a year recuperating after catching fire. The plot of their friendship mirrors Simone and Zaza’s. After their first summer apart, Sylvie realizes that her feelings for her friends can be classed as love. She pursues the friendship, always a little dissatisfied with its limitations; Andrée’s loyalties are split because of her devotion to her mother and because it turns out she’s long been in love with a boy she became close to during her bed-ridden year. The girls get older and Beauvoir writes about the religious divergences that arise between them when Sylvie loses her faith, the social engagements that take Andrée away from Sylvie, and Andrée’s love affair with the Merleau-Ponty–inspired Pascal, which turns out to be fatal.

It’s a book that unfolds through a series of intense, intimate scenes, saturated by the sensory world of childhood. Alone, and exquisitely lonely without Andrée, Sylvie takes walks through the countryside, stinging her fingers, tasting “the blackberries, dogwood leaves, the tart berries of the barberry shrubs.” The meadow where she sits at the foot of a poplar tree and reads a novel, enthralled by the wind and by the trees speaking to each other and to God, is vividly evoked. Beauvoir had documented passionate adolescent experiences in The Second Sex but now she keeps faith with them, celebrating the girls’ experiences of nature and of reading and of deep adolescent conversations: “We’d go and sit down in Monsieur Gallard’s office and not turn on the lights so we wouldn’t be discovered, and then we’d chat: it was a new pleasure.” The girls read together and Sylvie is struck by the way Andrée sees fictional characters as real people: “she surprised me because she seemed to believe that the stories the books told had actually happened.” It’s as though Beauvoir had to find a form that allowed her readers, too, to have this experience of profound, ingenuous readerly identification.

As in Elena Ferrante’s novels, adolescence is honored on its own terms—we can feel how devastating it is for Sylvie when she feels let down or unseen. At one point, away from her friend during their first summer, she sits down “at one of the garden tables with some blank sheets of paper and for two hours described to Andrée the new grass dotted with cowslips and primroses, the scent of the wisteria, the blue sky, and the great emotion in my soul.” Andrée doesn’t reply and then, when asked about it, says that she thought Sylvie had accidentally sent her homework to her: “I’m sure it was a study for a composition: Describe the springtime.” There’s a defenselessness to Sylvie’s pain, a preparedness to write openly about excruciating adolescent embarrassment, that Beauvoir couldn’t allow herself in the more staidly retrospective memoirs.

The commitment to the sensuous world seems to be a way of writing female passion. Beauvoir is clear that Sylvie doesn’t want a physical relationship with Andrée; Sylvie seems to be willfully directing her fantasies towards men. But the most genuine communication in the book is the conversations between the girls, and their most genuine feelings are for each other. “You never knew this, but from the day I met you, you’ve meant everything to me,” Sylvie eventually confesses.

In returning to this story, Beauvoir seems to have wanted to find a way to give voice to her most secret desires. She may have asked herself if her guilt at Zaza’s death was powered by the fantasized erotic life she had never quite acknowledged. Beauvoir at this point had had lesbian affairs, and had written in The Second Sex that “if nature is invoked, it could be said that every woman is naturally homosexual,” for every “adolescent female” the feminine body is “as for man, an object of desire.” But it took more courage to read erotic desire back into this early friendship. For this, she seems to have needed the turbulent modesty of the form she chose, a subterranean form that allows desire to emerge in sweaty nights of tossing and turning, or restless rambles through the woods.

It’s a shame, I think, that the novel has to end with Andrée’s death. What precedes it is so quietly realistic, so full of curiosity and open to the future they will forge together. Beauvoir’s talent here was for full-blooded description of young women lurching between poised intelligence, wistful godly leanings and coquettish charm, at that point when the androgynous child and the young woman collide in a body half-awkward and half-pleasurably aware of its own powers. For her this was a political matter, and it remains so because when society’s expectations for women suddenly flood in, the girl must decide whether to acquiesce or to resist. With the death, the story becomes fabular, though this may have been part of the appeal—existentialism was known for mixing fun and death.

Sartre advised Beauvoir not to publish it. As she put it in her autobiography, he “held his nose.” She adds here that she “couldn’t have agreed more: the story seemed to have no inner necessity and failed to hold the reader’s interest.” Sartre’s may have been good advice. Beauvoir was one of the most famous writers in the world, and had made her name with two heavyweight books that had redefined the possibilities of philosophy and the novel, and marked a turning point in sexual politics. This may not have been the moment to publish an apparently slight book about female friendship. But that phrase, “inner necessity,” seems overly dutiful, implying that novels require an Aristotelian intellectual dilemma.

There’s a fresh kind of writing present in the novel—a spontaneous,

ecstatic side of Beauvoir that was reined in by the more dutiful side of her

existentialism. Perhaps this novel holds out an alternative vision for her

development as a writer—more capricious but more capacious, more genuinely

curious about experience, less moralistic. It’s not a total success: It may be

that she was never going to be able to fully integrate her rapturous self with

her writerly self. But it’s hard to believe that Sartre, busy with his own

career and love affairs and his left-wing commitments, paid as much attention

as he should have done to this story of a friendship that had played out before

he met Beauvoir. He may have dismissed it partly because he was jealous of this

act of loving mutual self-fashioning from before she met him.

Luckily, Sartre is no longer Beauvoir’s gatekeeper and no one is holding their nose any more. Sandra Smith has more than done the novel justice in her stylish and readable translation. Margaret Atwood’s introduction to the book reflects on how Beauvoir inspired later generations (Atwood herself read The Second Sex in the bathroom in 1964 so that no one would see her) and points out that the dangers faced by Zaza remain as real as ever.

It’s hard now to know how to make sense of Beauvoir’s sense that Zaza had to die so that she could live. But what’s crucial is that this left her with the need to affirm her commitment to living at every turn. At one point Andrée asks Sylvie how she can bear to live if she doesn’t believe in God. “But I like living,” Sylvie responds. For Beauvoir this necessitated the philosophical life she went on to live, a life in which every choice had to be remade actively at every moment and in which she was constantly balancing her own freedom with the freedom of others. It was vital that she never lost the energy and the urgency of that girl in the white dress, gripping the grass in her fist. And these are the qualities that drive this story of adolescence told by a mature novelist committed to honoring an earlier stage in her becoming.