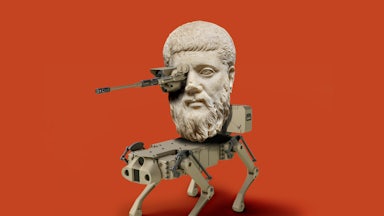

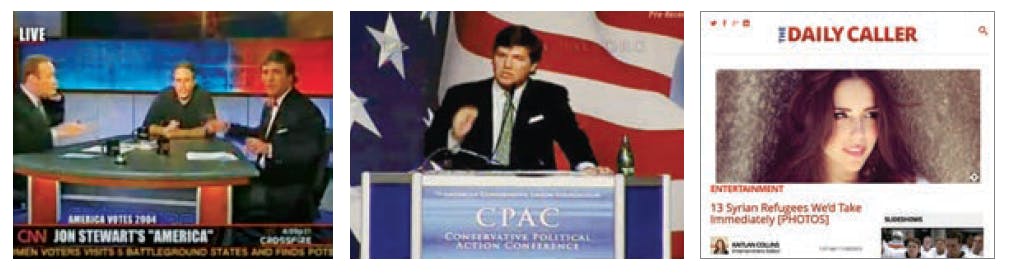

In February 2009, when he took the stage at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Tucker Carlson was in the midst of an identity crisis. Five years earlier, he had been a victim of what was arguably the first viral takedown of the internet era. Jon Stewart, then at the height of his Daily Show fame, appeared on CNN’s Crossfire, told the hosts they were ruining the country, and singled out Carlson in particular as a “dick.” Crossfire limped along for three more months before being canceled. Carlson then spent the next four years in the wilderness, appearing on Dancing With the Stars and hosting Tucker, which was canceled for low ratings in early 2008, on MSNBC, still a year or two away from deciding it would be the liberal cable news network. In 2003, a fresh-faced 34-year-old Carlson had released a memoir, Politicians, Partisans, and Parasites, which cataloged and celebrated his meteoric rise through the burgeoning world of cable news. Now, however, Carlson was on the verge of flaming out.

“I don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings, but I lived here in the 1990s and I saw conservatives create many of their own media organizations,” Carlson said in 2009, at Washington’s Omni Shoreham Hotel. “I saw many of those organizations prosper, and I saw some of them fail. And here’s the difference: The ones that failed refused to put accuracy first. This is the hard truth that conservatives need to deal with. I’m as conservative as any person in this room—I’m literally in the process of stockpiling weapons and food and moving to Idaho, so I am not in any way going to take a second seat to anyone in this room ideologically.” Watching the clip today, one can feel Carlson’s agitation; trained in the measured pace of TV speak—speaking too slowly makes you seem dumb, while speaking too quickly makes you seem nervous—he is talking at a speed somewhere between Lionel Messi and Usain Bolt.

“If you create a news organization whose primary objective is not to deliver accurate news, you will fail,” Carlson said, his voice building to crescendo. “The New York Times is a liberal paper … but it’s also a paper that cares about whether they spell people’s names right; it’s a paper that cares about accuracy. Conservatives need to build institutions that mirror those institutions.”

The audience booed. Then the heckling started. Carlson attempted to defend himself. “I’m merely saying that at the core of their news gathering is gathering news!” he yelped at one inaudible audience member. “Why aren’t there outlets that don’t just comment on the news, but dig it up and make it?”

Today, Carlson is the most important right-wing voice in the country. He has leapfrogged over Sean Hannity and Fox News’s other stars. Rising voices on the right, many mirroring Carlson’s faux-populist shtick, remain in his shadow. In July, Carlson drew more than three million viewers per night in his 8 p.m. Eastern slot, crushing competitors Chris Hayes (1.4 million) and Anderson Cooper (947,000).

On Fox, CNN’s Brian Stelter told me, Carlson “is the heir to Bill O’Reilly,” but without a boss at the network like Roger Ailes, Carlson “has even more power than O’Reilly ever did.” Carlson, in many ways, now occupies the space Donald Trump did only a few months ago. The outrageous things he says during his show quickly spread on Twitter. They’re blogged about as proof of just how deranged the right has become on any number of issues—crime, immigration, race, vaccines, education, health care. Often, Carlson turns that outrage into fodder for the next night’s program—a cycle resembling the one Trump rode to the White House with his rallies in 2016.

But his journey to the top of conservative media began with that CPAC speech. There has always been a nastiness and racial grievance at the core of Carlson, but, for much of his early career, he also sought a degree of respectability. At the time, there was still a somewhat respectable conservative media in existence. Carlson’s wobbly ascent in right-wing media eerily reflects the gradual stripping away of that respectability, as well as its increasing radicalization. “You could argue that Tucker Carlson’s career has been a Tour de France of conservative media. He has literally hit all the stations of the cross,” former conservative blogger Matthew Sheffield told me. “But all that’s changed is the object of his cruelty. Whereas before he was more of an Atlas Shrugged kind of guy—screw the poor. Now he’s decided to change the focus to let’s keep out these goddamned minorities.”

A year after his CPAC speech, Carlson would take a stab at creating the type of hard news–focused outlet he described. When he launched The Daily Caller in 2010, he vowed that it would “primarily be a news site” with a straightforward approach to the news: “Find out what’s happening and tell you about it. We plan to be accurate, both in the facts we assert and in the conclusions we imply.”

There wasn’t an audience. Within a few months, it was publishing fake news and outrage-driven commentary. The transformation of The Daily Caller is the Rosetta Stone moment of Carlson’s career, a period during which he learned his lesson. He never sought respectability again.

Tucker Swanson McNear Carlson was born in San Francisco in 1969. He was the older of two sons. (Carlson’s brother is named Buckley Swanson Peck Carlson, which suggests the family’s conservative bona fides.) His father, Dick, was a newsman turned banker turned politician, with a penchant for the kinds of red meat culture war stories his son would one day adopt: In 1976, at the end of his career as a self-described “gonzo reporter,” he outed Renée Richards, a trans tennis player who was applying to play in the U.S. Open as a woman. He would go on to lead Voice of America, the U.S. propaganda network, at the tail end of the Cold War.

Carlson’s mother, Lisa, abandoned the family when Tucker was six, an event he rarely speaks of. “There’s almost nothing I like less than people who whine about their childhood,” Carlson told GQ, the closest he’s come to opening up. “The majority of successful people I know had childhood trauma.” Four years later, when Carlson was 10, his father married Patricia Swanson, an heiress to the Swanson TV dinner fortune.

While at boarding school in Rhode Island, Carlson would meet his future wife, the daughter of the headmaster—the two are still married and have four children—and adopt his signature preppy style of a bow tie and blazer. His boarding school career was, by his own telling and everyone else’s, unremarkable but for one feature: He discovered debate and put it before everything else. Near the end of his time at the school, Carlson supposedly challenged any member of the faculty to debate him; no one accepted. Carlson then shipped off to Connecticut’s Trinity College, where he claims to have spent most of his time drunk. But this was the first PC era on campus, and, though an unremarkable student, Carlson was something of a conservative star. He thrilled at pissing off the hippies and lefties protesting on campus. When it was time to list his clubs and organizations in the school’s yearbook, Carlson cited membership in the nonexistent Dan White Society—a tribute to the murderer of Harvey Milk, the openly gay San Francisco politician of the 1970s—and the Jesse Helms Foundation (which does exist). “His personality was not similar to what it is now; it was exactly the same,” his college roommate (and future Daily Caller co-founder) Neil Patel said in 2017. Already apparent then were the twin pillars of Carlson’s career in conservative media. On the one hand, there is conservative pedigree: the bow tie, the well-heeled family, the debates. On the other, a fratty, trolly, attention-seeking side.

Carlson’s journalism career began on the respectable side of conservative journalism. He started out working for Policy Review, the journal then housed inside the Heritage Foundation, where he wrote sober, plodding pieces about conservative policy issues: the decline of Black public schools, the benefits of a private police force, and “HOW TO CLOSE DOWN A CRACK HOUSE IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD.” Carlson was, at this point, on the Buckley track. “I was impressed by the quality of his mind,” former Policy Review editor Adam Meyerson said. “We talked about C.S. Lewis, Whittaker Chambers, Nicaragua, and he had a contagious enthusiasm about ideas.”

After a brief sojourn as an op-ed writer at the Little Rock–based Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Carlson joined the nascent Weekly Standard, the Murdoch-owned opinion journal whose early staff also included David Brooks. Carlson told The Washington Post in 1999 that he “begged” friends and colleagues to persuade Weekly Standard editor William Kristol to hire him. He was also in contention for a position at the Clinton conspiracy–obsessed American Spectator, but he worried he would “be written off as a wing nut” if he accepted a job there.

His career quickly took off. Much of Carlson’s Weekly Standard work is witty but doctrinaire—gossipy dispatches from Clinton’s scandal-plagued second term and Newt Gingrich’s sputtering speakership. In Carlson’s first Weekly Standard piece, “MUMIA DEAREST,” which appeared in the Standard’s first issue, he contacts a number of celebrities and activists who were calling for a new trial for Mumia Abu-Jamal, the political activist who was sentenced to death for killing a police officer in 1982. In that piece, Abu-Jamal’s liberal supporters—people like Gloria Steinem, Molly Ivins, Roger Ebert, and Ben & Jerry’s founder Ben Cohen—are rendered dupes, people who don’t know the first thing about the person they’re defending. MOVE, the Black radical organization whose headquarters was bombed, is mocked as “the black nationalist cult best known for getting blown up by the Philly police in 1985.”

But interspersed are the pieces that made Carlson’s reputation and turned him, practically overnight, into a star. His 1996 profile of future Crossfire co-host James Carville is the gold standard: a sly and devastating hit piece. Dubbed a “populist plutocrat,” Carlson’s Carville is, above all else, a hypocrite and a poseur: a craven check-casher who cares primarily about lining his own pockets and sucking down expensive wines. And yet, Carville is also oddly sympathetic—one senses Carlson recognizes a fellow traveler, another rakish opportunist who just happens to be playing for the other side.

In these pieces, we see the nucleus of Carlson’s later persona: He cares not one iota for public policy; what gets his blood up is hypocrisy, particularly when it comes from women, people of color, and LGBTQ people. He continued writing for The Weekly Standard but became one of the most sought-after long-form magazine writers in the country, publishing pieces for Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, and, later, The New Republic.

In 1999, he profiled George W. Bush for Tina Brown’s Talk magazine. Bush was running as “a compassionate conservative,” a Christian of deep faith, and a moral leader who could lift the country out of the debauched Clinton years. Carlson’s profile was glowing—mostly. But he also caught Bush’s naughty, frat boy side: He quotes the Texas governor saying “fuck,” over and over again, something Bush’s communications director, Karen Hughes, went to great lengths to deny. More chillingly, Carlson also noted Bush mocking Karla Faye Tucker, a recently executed death row inmate in Texas: “‘Please,’ Bush whimpers, his lips pursed in mock desperation, ‘don’t kill me.’”

Carlson “was really a kind of hilarious—at that time—gadfly scamp,” Brown said. “Tucker is a fantastic writer. One of the things I find regrettable in all of this is that Tucker had an almost Evelyn Waugh–ish ability to skewer people and make it really funny. He had such a hilarious touch and truth. I thought he had the makings of a top talent.”

Whether he was top talent or not, Carlson’s magazine writing career was over almost as soon as it began. While he was rising through the ranks in Washington, befriending liberal and conservative editors along the way, he was also becoming a television star.

As a writer, Carlson had a gift for irony and for bringing out stark, but often submerged, truths about his subjects. He was a bomb-thrower—he clearly idolized both Christopher Hitchens and Hunter S. Thompson—but the smug 15-year-old debater and “Dan White Society” member was also cloaked. Carlson relished the revealing of unsavory details about his subjects, but his brash and glib side was largely smothered by the nature of the assignments. Television brought out the worst in Carlson—and it made him an even bigger star.

Carlson described his break into TV as a lucky one: “If O.J. Simpson hadn’t murdered his wife, I probably wouldn’t be working in television,” he wrote. CBS needed pundits to cover the O.J. trial, and Carlson answered the call; he quickly became a cable news regular, before hosting his own debate show on CNN with liberal Bill Press, beginning in 2000. That show was a disaster—Carlson was still figuring out what worked on TV—and it was quickly canceled. But the bow-tied Carlson had found a home at CNN, which quickly slotted him in as the fratty, well-heeled Republican on Crossfire, where he would shout at liberals Paul Begala and James Carville every afternoon. Carlson, as ever, understood the assignment: He was there to bark and bicker and to gleefully represent Team Red.

In 2003, not long before Stewart destroyed Crossfire, a 34-year-old Carlson published a memoir, Politicians, Partisans, and Parasites: My Adventures in Cable News. The book is a slight and sometimes funny portrait of how cable television works: Conflict is good, intelligence is bad. Its epigraph is Larry King’s advice for succeeding on TV: “The trick is to care, but not too much. Give a shit—but not really.” Carlson buys it whole cloth, pitching himself as someone almost giddy at the prospect of nightly debate, even if he doesn’t actually care about what’s at stake. “Nuance, needless to say, is the enemy of clear debate,” he writes. Later, he notes that “television magnifies almost everything about a person”—an interesting revelation from someone whose entire TV character was built around pompousness. Carlson was, to an extent, playing a character, but it was one nearing its death. He was the blue-blooded, country club Republican; a khakis-wearing suburb-dweller who cares about national defense and marginal tax rates. The GOP establishment was transforming—but Carlson didn’t realize it yet.

Stewart’s disemboweling of Crossfire is arguably more well-known than the program itself at this point. The Daily Show host’s ultimate argument—that the series was “hurting America” by injecting partisanship into everything—stands today as both prescient and a tad naïve. By 2004, Crossfire’s weaponized partisanship had spread well beyond CNN; there was no turning back the clock to an era of sober, reasoned political debate on cable television. But what stands out now when one watches the clip is something different. “Real anger is as rare on television as real discussion,” The New York Times’s Alessandra Stanley wrote about Stewart’s appearance at the time. Stewart is actually very angry; Carlson, Begala, and Carville mostly just fumble around. Faced with real anger and real debate, they have nothing to offer. Carlson is revealed as just another phony—the exact kind of person Carlson the magazine writer would have skewered.

Thus began Carlson’s time in the political wilderness. He was, during this stretch, still very much a member of the Beltway Establishment. But he quickly realized that the country club, GOP establishment shtick wasn’t working. He ditched the bow tie. He rebranded himself as an Iraq War critic and a kind of libertarian. He appeared on Dancing With the Stars in 2006 and was voted off almost immediately. He got a show on MSNBC, Tucker, that was forgettable and utterly conventional—Carlson’s guests were, by and large, familiar politicos. It was canceled in March 2008, less than four years after the Stewart incident, and no one seemed to miss it.

Carlson appeared to have nowhere to go. Speaking to The Hill in 2008, he joked about being unemployed but largely came across as lost. “His ideal next step is to host Jeopardy! and a Sunday politics show,” Betsy Rothstein wrote. “I’m open to everything,” Carlson said. “Something interesting always happens.”

During this period, Carlson’s meanness began to warp into cruelty. His racism and homophobia, long parts of his journalistic oeuvre, became even more pronounced. As he ditched the establishment GOP cloak, he leaned more and more heavily into his fratty side. Television helped it along, of course. His last award-winning magazine feature, a 2003 Esquire piece about traveling to Liberia with a group of Black preachers, prefigures the types of arguments that would appear again and again on his show. “The idea that I’d be responsible for the sins (or, for that matter, share in the glory of the accomplishments) of dead people who happened to share my skin tone has always confused me,” Carlson wrote. “I grew up feeling about as much connection to nineteenth-century slave owners as I did to bus drivers in Helsinki or astronomers in Tirana. We’re all capable of getting sunburned. That’s it.” In his 2003 memoir, moreover, he names a woman who accused him of sexual assault in a Kentucky restaurant. (She later recanted; her lawyer did not respond to a request for comment.)

Between 2006 and 2011, Carlson made numerous appearances on a radio show hosted by Bubba the Love Sponge, a Florida-based shock jock. Carlson repeatedly used racist and homophobic language. He lamented that “everyone’s embarrassed to be a white man” now, even though white men should get credit for “creating civilization and stuff.” Iraq, the invasion of which he had cheered on, was “a crappy place filled with a bunch of, you know, semiliterate primitive monkeys.” He questioned Barack Obama’s Blackness because he is of mixed-race parentage. He joked with Bubba about loving him “in a faggot way.” In another call, he joked about teen girls sexually experimenting at boarding school and referred to women as “pigs” and “whores.” Many of these comments surfaced much later, but Carlson also rarely bothered to hide them: In 2007, on his MSNBC show, he boasted about beating up a gay man who made an advance on him in a public bathroom.

But Carlson still wanted to hold on to his place in the establishment—you don’t talk about hosting Jeopardy! or a Sunday show unless that place is secure. The Daily Caller represented a way back in. Carlson may have pitched it as a Times for the right, but it was closer in spirit to Brown’s recently launched Daily Beast or his sometime friend Arianna Huffington’s HuffPost. Its name, like Brown’s, recalled the gossipy English rags of old, though it lacked the literary élan of The Daily Beast, which takes its name from a fictional newspaper in an Evelyn Waugh novel: Here would be a muckraking, news-breaking outlet that would advance conservative priorities rather than liberal ones. The right, as Carlson said at CPAC, had been losing the arms race for years. Now, it could finally catch up. It also represented an attempt to create an establishment conservative media outlet in Carlson’s image: one less buttoned-up, more freewheeling and mercenary than your standard fare. Here would be a publication for conservatives like Carlson: sharp-elbowed, witty, and ideological, but without resorting to partisanship.

The Daily Caller began practically as an outgrowth of the GOP. His co-founder, Neil Patel, was not only Carlson’s old college roommate but a former top aide to Dick Cheney. The site’s opinion editor was a former RNC press secretary. The whole thing was funded by Republican mega-donor Foster Friess. Carlson told Human Events that the site would be opposed to the Obama administration, which he said was behind “a radical increase in federal power ... a version of socialism.” But he also insisted to The Washington Post that he wasn’t going to be a cheerleader for the GOP. “Our goal is not to get Republicans elected,” he said. “Our goal is to explain what your government is doing. We’re not going to suck up to people in power, the way so many have. There’s been an enormous amount of throne-sniffing. It’s disgusting.”

Friess, meanwhile, thought that his erstwhile partners would help remake America. “Tucker and Neil present a huge opportunity to re-introduce civility to our political discourse,” he told the Post. “They want to make a contribution to the dialogue that occurs in our country that has become too antagonistic, nasty and hostile.”

The whole thing was a disaster. The site’s traffic was terrible; there wasn’t an audience for serious, independent, investigative-minded conservative journalism. Writing in Salon in 2012, Alex Pareene noted that this was wholly predictable. “Carlson’s Daily Caller was supposed to be a home for edgy, independent voices and serious, well-reported journalism from a conservative perspective,” Pareene wrote. “No one actually wants that—if they did, it would exist, right?—because the online right-wing audience simply wants to be told reassuring and outrageous lies.”

And so the Caller quickly resorted to stunts. There were pranks, like buying keitholbermann.com and redirecting it to the site’s negative coverage of Olbermann’s MSNBC show. And there were a lot of photos of attractive, scantily clad women. “At first, The Daily Caller was trying to do more substantive reporting or analysis in opinion columns, but they weren’t getting coverage or numbers,” Matthew Sheffield told me. “So they started the side-boob beat to try to juice their numbers—it worked so well that they actually spun off that content into its own website.” The Daily Caller boosted its traffic with posts like “THESE PHOTOS OF KATE UPTON AS A SEXY HOUSEWIFE WILL BLOW YOUR MIND,” “EMILY RATAJKOWSKI USES HER HAND AS A BRA IN SCANDALOUS NEW PHOTO,” and “13 SYRIAN REFUGEES WE’D TAKE IMMEDIATELY,” a story that went on to note that the refugees were “Syria-sly hot.”

The Caller’s journalism took a similar nosedive that began with a bogus, sensationalist exposé that would define Carlson’s bad faith approach to journalism going forward. In the summer of 2010, The Daily Caller pushed a delicious scoop: The nation’s journalists were engaged in a vast conspiracy and were colluding together on a private listserv, Journolist, to help define the news agenda for the nation and push the country to the left. The Daily Caller published story after story about how it had caught the journalists red-handed, that their correspondence proved they were a kind of cabal. The whole thing was a sensation; one Washington Post reporter, Dave Weigel, lost his job over emails he sent to the group, which included more than 400 journalists, economists, historians, and the like. (Weigel has since been rehired by the Post.)

There were several problems, however. For one, the stories misrepresented a number of key details, making the findings appear much more sensational. The Daily Caller repeatedly pulled emails out of context to make them seem worse. The headline of one story claimed that the listserv wanted the government to “shut down Fox News,” something that the contents of the emails didn’t actually support. Most of the participants, moreover, were liberal journalists and commentators. The Caller hadn’t unearthed a secret society of buttoned-up Times reporters discussing how best to move the country toward anarcho-syndicalism. It had found liberal commentators like Ezra Klein (Journolist’s founder), Matt Yglesias, Spencer Ackerman, and Chris Hayes talking in a way you would expect them to (TNR editor Michael Tomasky was also a member).

And then there was how the list was uncovered. Carlson had written to Klein to try to join; he was rebuffed. And so, The Daily Caller snuck on. Someone impersonated Max Brantley, the liberal Arkansas Democrat-Gazette journalist, and got added. (That person may very well have been former Democrat-Gazette employee Tucker Carlson.) The whole episode had much more in common with James O’Keefe’s bogus “stings” than it did with anything resembling the sterling journalism Carlson claimed he was after.

From there, things didn’t get much better. The Daily Caller pushed birtherism, it published O’Keefe’s lesser videos, it portrayed Trayvon Martin as a thug. It tried to take down Media Matters and Bob Menendez with shoddy “scoops” that quickly fell apart. The site published several figures on the alt-right, and its deputy editor was forced to resign after it emerged he had written for a white supremacist publication under a pseudonym. The site was nothing like what Carlson claimed he intended it to be. But it flourished. And it also helped resuscitate his career. After years of seeking mainstream acceptance, Carlson stopped. But he did show a knack for driving the red meat culture war stories that fed the right-wing media ecosystem. And, in an era of growing frustration with RINOs and other Republican elites, Carlson also showed a knack for biting the hand that fed him—with one exception.

“I have two rules,” Carlson said in 2015 after he killed a piece critical of Fox News. “One is you can’t criticize the families of the people who work here. And the other rule is you can’t go after Fox. Only for one reason, not because they’re conservative or we agree with them [or] because they’re doing the Lord’s work. Nothing like that. It’s because I work there. I’m an anchor on Fox.” In 2009, a year after his MSNBC show went up in flames, Carlson got another shot at Fox News—he began as a contributor and occasional guest host. His ascent was slow, but steady. By 2013, he was hosting Fox & Friends’ weekend hour. Three years later—eight years after his last bite at the apple—Carlson got his own show, not long after then-Fox News chief Roger Ailes brought him to the network.

Over the last four years, as his Fox News show adopted more and more radical positions—vaccine skepticism, white nationalism, his growing support for illiberal and anti-democratic right-wing regimes around the world—many who were once in his orbit have wondered what happened to Tucker Carlson. That question has fueled countless magazine profiles and cocktail hour conversations.

The answer is perhaps less exciting than the question seems. Carlson is, in many ways, the same as he has ever been. He is whiny and petulant. He insists that he is a rebel, shucking elites of both parties and decrying phonies and partisans. But he advocates again and again only on behalf of whites, particularly well-heeled ones. He contradicts himself constantly and seems to have no fixed ideology at all, beyond a sense of racial solidarity. “Ultimately, I’m just not a guilty white person,” Carlson wrote for Esquire in 2003. Over the ensuing two decades, he has only gotten angrier and angrier at the suggestion he should feel guilty for being white and more insistent that groups advocating for Blacks or homosexuals or anyone who isn’t white exist solely to take what is rightfully his and—as he insists frequently on his television show—yours.

Carlson’s narrative is somewhat different from Trump’s. “In a weird way, Tucker isn’t just advocating on behalf of white genocide,” Media Matters president Angelo Carusone told me, referring to the widely held idea on the right that the white race is going to be replaced. “He’s also somebody who does weave in and blur the lines between white genocide and Americana genocide. That’s really his culture war: It’s not just white people and white culture that’s being addressed, but it’s also Americana. You can’t hang Norman Rockwell paintings anymore! It’s all that stuff.”

Carlson glommed on to what Trump was doing faster than most. Writing in Politico in January 2016, when most conservatives were still aghast at Trump’s rise, Carlson made the case for Trump, sort of. It also just happened to be the case that Carlson would make again and again on his television show. Trump, he argued, was “Shocking, Vulgar and Right.” His ascension was an indictment of a corrupt and effete political class, both right and left. Trump’s Muslim ban, Carlson argued, was perfectly reasonable, because “millions of Muslims” had immigrated to the West in recent years, and many hadn’t assimilated. “What’s our strategy for not repeating it here, especially after San Bernardino—attacks that seemed to come out of nowhere? Invoke American exceptionalism and hope for the best? Before Trump, that was the plan.” Again and again, you get the same message. Republican voters had been betrayed by their leaders. The elites hate Trump—that fact alone, Carlson notes, is proof he’s doing something right.

In that Politico piece, you got the basics of Carlson’s Fox News show, with one exception: It was about Trump. Carlson’s rise at the network was slow and somewhat stealthy, in part because his coverage of the president, compared with his compatriots’, was rare. Sean Hannity and the buffoons on Fox & Friends treated Trump like Dear Leader. Carlson often acted as if he didn’t exist at all.

In doing so, he has, more than anyone else in America, taken up the mantle of Trumpism, particularly with Trump himself struggling for attention and airtime. “People used to say during the Trump years, ‘what would happen if we got a Trump that was really smart?’ In a way, Tucker is fulfilling that dark prospect,” New York University journalism professor Jay Rosen told me. “The reason he is inheriting Trumpism is that he has a similar gut feel for demagoguery. Sensing the audience’s bloodlust is the one thing he’s good at.”

Carlson has aggressively focused on culture war stories that seemed smaller than much of what else was on the news, particularly during the Trump years: Immigrants were littering a lot, private schools were teaching wokeness, the metric system was a conspiracy theory. He has focused extensively on minor journalism faux-controversies—he loves to mock female journalists for complaining about online harassment in segments that, of course, result in waves of online harassment—but also on weird animal stories: raccoons that act like zombies, pandas having aggressive sex. While Fox News tightly focused on following Donald Trump anywhere he went, Carlson pursued stories that only he covered.

Nothing exemplifies Carlson’s shtick quite like his repeated questioning of the purpose and efficacy of the Covid-19 vaccine. For Carlson, the vaccine is a potent metaphor for the creeping hegemony of Democratic elites. “Democrats believe vaccines are the answer to everything. ‘Shh. Don’t ask questions. Just take the shot,’” he told viewers late last year. At the same time, it is also an example of how elites police discourse to hold on to power. “From the moment that coronavirus vaccine arrived, the most powerful people in America worked to make certain that no one could criticize it,” he said in February. In July, Carlson compared vaccine passports to Jim Crow.

Above all, Carlson portrays bad faith attacks as good faith inquiries, simple questions that should be answered by the powers that be. “Don’t dismiss those questions from anti-vaxxers,” Carlson said in March. “Don’t kick people off social media for asking them. Answer the questions.” And: “It turns out there are things we don’t know about the effects of this vaccine—and all vaccines, by the way. It’s always a trade-off.” Carlson is raising concerns with little basis in fact under the guise of asking legitimate questions. The answers to these inquiries exist. Carlson simply pretends they don’t. The result is a mendacious muddle, in which only one conclusion can be drawn: The elites are hiding something—likely something very sinister—from everyone else. Only Carlson has the courage to state plainly what’s under everyone’s nose.

To his credit, he has focused more aggressively on the perils of economic concentration and military intervention and occupation than many of his colleagues at Fox—or his compatriots on the right—have. Many saw Trump’s rise as an opportunity: Here was someone gleefully in tune with the anger of large swaths of the country, but who struggled to come up with a coherent ideological vision beyond demagoguery and reaction. Carlson is skilled at finding targets for that anger, whether they be school board members or female journalists, and directing his viewers’ attention there. If you want to know who is destroying America, tune in to Tucker Carlson Tonight.

Carlson is practically millenarian. His obnoxious, fratty persona in his early television days and early writing career has given way to something shriller. Carlson hectors. He tilts his head, adopting a look of disappointment like a confused golden retriever that, having become used to prime rib, is suddenly given kibble. He remains boyish, but has gotten puffy and bloated; he squints. Above all, he’s pissed off at what they are doing to you.

“Bill O’Reilly’s question to the viewers was always, ‘Who’s looking out for you?’” CNN anchor Brian Stelter told me. “Carlson has answered the question: ‘No one is looking out for you.’ It is a doomsday view of America. It is a doomsday view of the world. Whereas O’Reilly allowed for some light to shine through—with the War on Christmas, it was never guaranteed that Christmas was going to lose! On Tucker Carlson Tonight, Christmas is dead and buried.”

This is, ultimately, an evolution—not just for Carlson but for conservative media. He has seen the anger that fueled Trump’s rise and directed it, again and again. He has no time for hope or silver linings. Instead, the message is simple: This is an existential struggle for the future of the country. Gone are pieties to conservatism. Gone is even a facade of nuance. Gone is an attempt to understand. Gone is any semblance of ideological consistency. Instead, you get the present and future of conservative media: a squinting Tucker Carlson barking about the country going to hell, forever.