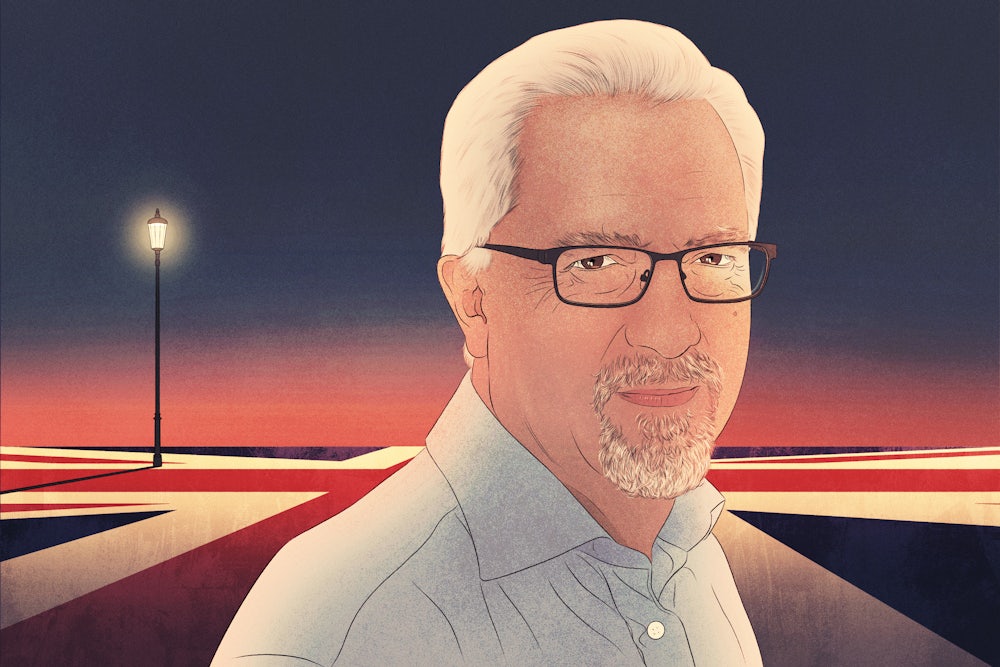

It is hard to think of another living writer who produces structures as ebullient and dirigiblelike as Alan Hollinghurst does. His first novel, The Swimming-Pool Library (1988), depicts London streets, tube stops, pubs, and gym locker rooms as an infinitely detailed region of aspiration, desire, and finely tuned observation. In The Stranger’s Child (2011), poetry isn’t a matter of words on pages, but how those words pulse with physical and emotional resonance over a century of insular Oxbridge social life. In fact, it’s hard to think of anybody else today who writes what Henry James would describe as a contemporary “romance,” work so filled with self-sustaining imagination that it lifts off the ground and takes you to places not entirely of this world.

His new novel, Our Evenings, recounts a young man’s coming of age (and eventual coming into old age), and like most of Hollinghurst’s fiction, it’s about living one’s life for beautiful things: music, paintings, theater, architecture, and other people (especially, in this case, beautiful male people). In his evenings, David Win seeks ephemeral (and largely indefinable) pleasures. The son of an adventurous seamstress and a Burmese man he never meets, he spends his first several years with his mother, watching her create her unusual and inventive dresses and scarves, wandering the streets with her, or watching Hollywood movies at the local cinema. Later, he passes evenings at the Record Club, where, in the company of his possibly too attentive male tutor, he enjoys the piano music of Janáček. (One of the tunes—a reflective, occasionally discordant solo piece—is itself entitled “Our Evenings.”)

Still later, his evenings are occupied by his performances with a traveling theater troupe, as he learns his way from one long-term sexual relationship to another. (In this cautious approach to relationships, he is quite unlike William Beckwith, the protagonist of The Swimming-Pool Library, who never seems to visit a London square or tube stop without finding a man he wants to take home.) Eventually, there are evenings of approaching old age, when the people he loves are starting to die all around him, and David begins assembling his memoirs.

Our Evenings is a much calmer, cooler novel than Hollinghurst’s best-known works. While most of it takes place in David Win’s youth, the most striking passages develop from the long, lyrical, elegiac pages of his late years, as the evenings seem to be passing by more quickly and growing ever more brief. Unlike Will in The Swimming-Pool Library, or Nick Guest in The Line of Beauty (2004), David never turns his back on his family or acts ashamed of them. Being gay and biracial, he has learned to live with (if not accept) the casual racism of his fellow Brits, even while he’s annoyed to be mistaken for biracial actors who don’t look remotely like him.

David spends a lifetime loving a few men wisely and well, but either leaves them for someone else or is left by them in turn—until, by the end of this rich and sometimes aimless novel, the forces of Brexit-adjacent dissolution and rage come gunning for him. Though Our Evenings presents itself as the recollections of a sensitive soul, its political heart seems to beat with the recognition that Britain had something beautiful once and threw it all away. And an elegy is the best that David—and Britain—still have in them for their final evening reflections.

Much like Hollinghurst’s best and wonderfully rereadable Booker-winning fourth novel, The Line of Beauty, Our Evenings is structured around the protagonist’s affection for a well-off, upper-middle-class family, and the shining lives they live inside their decorous homes. Unlike the horrible (while charming) Thatcherite Feddens in The Line of Beauty, Mark and Cara Hadlow are modest, generous, and liberal, and they award David a scholarship that helps him journey far beyond his modest beginnings.

They develop a genuine fondness for David that he reciprocates over several decades, but unfortunately this means he must spend occasional time with their unpleasant, even sadistic son, Giles, whose secret adolescent cruelties won’t be entirely revealed until late in David’s recollections, as if they are difficult for David to put down on paper. Giles will eventually alienate his parents and half the country by becoming a leading Brexiteer, and author of the polemic Our Laws, Our Borders.

In the same way that, for Nick, the Feddens’ home in Notting Hill represents life’s finest pleasures, for David the Hadlow family’s country home appears the heart of the world. Climbing to the top of a set of hills known as the Rings, he should be able to view five English counties, from London to Birmingham:

Where the boundaries divided one county from another was impossible to guess on the gleaming expanse of the plain below, where details were soon lost in the wash of the April light. I shivered, gooseflesh under my shirt in spite of the sun; though now and then there was a quiet lull, ten seconds of scented warmth tucked up in the cold wind that flowed endlessly over England. I ran off a few yards and gazed at the featureless circle behind us, the scruffy grass dotted with sheep droppings, though no sheep could be seen or heard.

It’s a view that allows David to see himself involved with an entire country where, until now, he hasn’t felt entirely at home—even while Giles is there to continually remind him of his status as the always-available victim for boys who are wealthier, and crueler, than himself.

Despite the briefness of this youthful visit, David always yearns to return to this vision of the wide, unified country. Giles’s grandmother, a successful actress, warns young Dave that, despite his talent, he will find it hard developing his acting career “because of how people see you,” and suggests that, to avoid British racism, he might consider looking for roles in radio. Undeterred, Dave spends 40 years as a professional actor, sometimes on television, but more often onstage, and most memorably in avant-garde performances with a multiracial troupe whose members aren’t afraid to take off all their clothes in controversial productions, or present “politically disruptive readings of the classics” through “an unusual range of races on stage.”

The arts bring David closest to a sense of belonging. Like most of Hollinghurst’s postwar gay characters, Dave occasionally meets older men who have managed to live out an aesthetic ideal. There is, for instance, the writer Derry Blundell, who has built a home full of exquisite things to memorialize the love of his life (yet another artist). In his house, “oppressively full of furniture, objects and pictures,” it’s hard to tell “what was fine art and what was mere memorabilia.” For all David’s desire for finery, it’s a setting in which he does not quite feel at ease: “I tensed with the nearly subliminal sense I had now and then, in the house of someone new, of entering a trap, however gilded and apparently comfortable.”

Characters like Derry appear and disappear in this slowly accumulating novel almost as whimsically as fellow passengers on a train or subway. After a long narrative passage describing Dave’s first love affair, with a man named Chris, the character Chris vanishes entirely from the novel, and Dave moves on to someone else. And other characters, who bristle with charm and verisimilitude—such as Dave’s friends Ken and Edie—arrive and depart over the decades without providing anything that resembles narrative significance. It eventually grows a bit wearying to pay attention to characters, or to grow somewhat interested in them, when they never seem more interesting to the author than simply as objects of examination until the next ones come along.

Meanwhile, the sinister character of Giles is in the shadows, plotting, forgotten by Dave for long periods of time. The most significant political events of this novel build offstage; and when they finally come to fruition—Britain’s vote on Brexit, the outbreak of the pandemic—they occur way out at the edges of the narrative. We first learn of Giles’s role in Brexit in a line in an obituary of his father; Covid is ushered into the story simply with a reference to “the first cases.” We get allusions to the news, but no direct action until, in the novel’s sudden and rather unsatisfying conclusion, the racial divisions stoked by Giles et al. startlingly interrupt Dave’s life. David’s partner sums up the xenophobia that permeates British life in early 2020: “in a few weeks history went backwards by a century.”

It is as if, in the scenes of aesthetic pleasure Hollinghurst’s characters are continually weaving around themselves, there is always some ugliness out there in the world, just waiting for its opportunity to move in.

In his Paris Review interview, Hollinghurst recalls: “My old friend the novelist Lawrence Norfolk used to say, ‘You write marvelous descriptions, but why do you have these terrible plots?’ I like evoking atmospheres and analyzing relationships and feelings, but plot I feel faintly embarrassed by.” His novels at times get so tied up in multiple reflections about some past event that they never feel like they’re moving forward at all. In The Swimming-Pool Library, William Beckwith’s picaresque sexual adventures are set up as a foil to the diaries of an old man (William’s friend calls him the “queer peer”), recounting life back when gay men couldn’t be as open about their lives as they are in the novel’s present, the 1980s, and the story loses focus in nests of ironic observations and juxtapositions.

And in both The Sparsholt Affair (2017) and The Stranger’s Child, the central passionate relationships—between two male Oxford students in the first, and between two Cambridge ones in the second—come to their narrative conclusions about 300 or 400 pages before the novels do; and so the rest of each novel traces the convoluted, many-decades-long inability of other people to understand what happened back in the day, or why these already concluded relationships were significant. Often the survivors and family members, such as David Sparsholt’s gay son, Johnny, can’t even comprehend gay life before it was decriminalized; and just as the “scandal” that bears David’s name (an echo of well-known British sex and politics scandals, such as “the Profumo affair” or “the Thorpe affair”) is never mentioned, the truth of the past remains firmly closeted along with him.

A remarkable exception to the plotless, multiperspective ambivalence that infuses his books is The Line of Beauty—perhaps one of the past century’s finest novels. While it covers a stretch of history over the mid-’80s that coincides with Margaret Thatcher’s government, it’s a manageable span. Even better, it is told from one point of view, that of Nick Guest (yet another of Hollinghurst’s twentysomething Oxford graduates), who moves in with the Feddens—a Tory MP, his wife, his daughter, and their son, Toby, a fellow Oxford student on whom Nick has a crush. Offered an attic room in their home, he mixes happily with the Tories who have recently come to power, bringing their glib and self-disparaging humor with them; they shrug off their importance so they don’t seem vulgar, even while secretly harboring vulgar habits of privilege, chauvinism, and sexual hypocrisy. For Nick, wandering through their grand homes is far preferable to visiting the disconnected artifacts in his father’s antique shop back in Northamptonshire. In their wealthy part of London, people live with the precious objects that Nick can only dream of purchasing in small, selfish bursts. Nick’s patron saints (and the patron saints of many a Hollinghurst protagonist) are Oscar Wilde and Henry James, who represent everything that matters most to him: art and making a life alongside the sort of people who live for it.

The orchestration of The Line of Beauty is perfect, filled with lovely embellishments; and the clear, direct set of storylines carries through a half decade of Tory misrule while Nick worries about his hair, and how he looks at parties. At the same time, almost unbeknownst to him, and visible just on the peripheries of conversations and social encounters, the cumulative effects of harsh policy are becoming clear. Nick’s friends lose jobs, get sick, and gradually grow aware of the AIDS epidemic, which seems to concern the Tories (like the Reagan Republicans) not much at all. And for all his love of beauty, the deep ugliness of the Feddens doesn’t concern him until they throw him out for becoming the subject of a scandal—even while the senior Fedden becomes involved in a scandal of his own. And Nick exits the novel on the way to an AIDS test.

Nick and Hollinghurst’s other central characters often seem divorced from, or at least far removed from, political concerns; and even when they recognize something isn’t quite right with their country, they don’t spend time thinking or talking too much about it. Usually, they seem to believe that political differences can be measured in degrees of good or bad taste. After spending an agreeable afternoon at Toby Fedden’s birthday party at a “Victorian monstrosity” of a country estate, Nick happily circulates among the artworks and artifacts (including a Cézanne, and an “escritoire of the dear old Marquise de Pompadour”), and the closest he can come to a political critique is to tell his boyfriend, Leo, that the hosts suffer from “a sort of aesthetic poverty.” To which Leo sensibly replies: “I wouldn’t say that was their main problem…”

The desire to belong to exalted homes, families, and lovers is the central preoccupation of Hollinghurst’s young men. David Win, however, establishes relatively less grand and presumptuous ad hoc families as he goes through life. He adjusts to his mother’s live-in relationship with another woman, and then the eventual death of her partner; he takes his mother home and cares for her until she dies and, many months later, when he can bear to look at them, discards the glowingly embellished clothes she spent her life designing and constructing.

He is not as easily fooled as Nick is, and so cannot be so thoroughly disillusioned. But like Nick’s, his political sense is unsophisticated; and he seems to share Nick’s feelings that good politics versus bad politics may have something to do with good versus bad taste—as when he watches a Newsnight interview featuring Euroskeptic Giles, and gets a chance to compare Giles’s sense of decor (and good living) with that of his parents:

It was a big West London house, perhaps not far from his parents’ place and not unlike a smaller version of it—at least until you stepped inside. A shot in a kitchen where everything was paneled in carved oak, like a Bavarian inn, then a minute in a posh sort of Georgian drawing room with paintings out of focus, before we got down to business in Giles’s study, leather armchairs, signed photo of Thatcher, framed prints, and a heavy male atmosphere of a standard kind. Over the fireplace was a portrait of Giles himself, of the sort that dutiful colleagues commission on someone’s retirement—clearly Giles had decided to get in first. I thought how his father, in that same spot in his study, had hung a large Prunella Clough that was like an electric circuit, where the mind travelled happily between the blue flashes of ideas.

For Hollinghurst, the difference is obvious: Bad taste is when people hang their own pictures on the wall; while the kinder, gentler Hadlows set up “electric” connections between people through beautiful things. There are two types of artists in Hollinghurst: those who try to tell honest stories about how they see the world, and those like the eminent writer Victor Dax in Sparsholt, who proudly presents himself for lionization at highly paid university speaking gigs and seems unwilling to let anybody understand his work better than he does. Good artists throw their work into the world and set it free to float merrily (or dolefully) downstream. But the selfish, controlling ones refuse to allow for any interpretations of their work but their own.

The problem with post-Brexit Britain, Our Evenings seems to conclude, is that the bad artists won, and turned back the clock on the multiracial, multilingual, and trans-experiential England of David’s (and Hollinghurst’s) young adulthood.

The parallels between Hollinghurst and Henry James (a writer with whom Hollinghurst recalls having been “completely obsessed”) seem almost too obvious. They both share an interest in artists and their work, and approach social and political issues as, at their best, matters of adornment and beautification, and, at their worst, as deceptions. At the same time, they couldn’t be more different stylistically—for while James’s prose is almost exhaustingly evanescent and subjective, Hollinghurst has a much keener, more untiring eye when it comes to the specifics of what people see and how they speak. James is also less didactic. Which cannot be said of Our Evenings, with its message that Brexit, and Britain’s retrograde politics, have been a matter of Giles-ish chauvinism, pettiness, bigotry, and pointless rage.

In 40 years of fiction writing, Hollinghurst has been a sublime writer of scenes, human relationships, and affections, but his plots are often so lackadaisical that reading them sometimes feels like being locked in one of his many-dozens-pages-long dinner parties. And while the political “message” of his latest novel tends to detract from its greatest pleasures, it does convey one view that feels quite true: There is something about current politics that is deeply, basely, and irremediably ugly. And no matter how hard we may try to protect ourselves from that ugliness, or surround ourselves with its antithesis, it’s almost sure to find us.