Amid the many circuitries of outrage, distraction, and algorithmic surveillance that now go by the name of online life, the temptation to log off and unplug for good grows greater by the nanosecond. Reflection and introspection are in desperately short supply when so much of our common world is strategically programmed and miniaturized to serve as maximally viral or trending “content.”

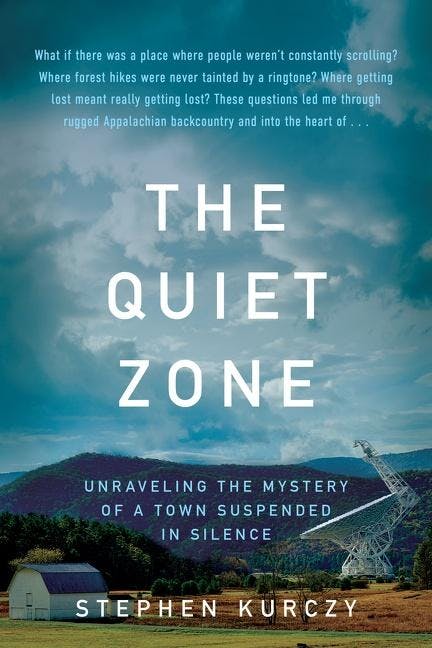

As demand for blessed offline silence grows, the search is on for anyplace that might be pressed into service as a reliable oasis of calm and disconnection—and as it happens, there’s a large stretch of land in rural West Virginia that’s been all but designed for the job. In 1956, the federal government designated the town of Green Bank as the site for a massive installation of a dozen radio telescopes and a complex of research facilities called the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. And as Stephen Kurczy recounts in The Quiet Zone, his tour through Green Bank and its environs, the order to build the NRAO came with hard and fast strictures on modern communications devices. The Green Bank campus needed “to be largely free of radio noise … in a sparsely populated area surrounded by mountains and at least fifty miles from the nearest city.” State and federal legislation made the operation of any electrical equipment on the spectrum set aside for NRAO a crime, which could result in state fines of up to $50 per day in a poor Appalachian subsistence economy. The broader National Radio Quiet Zone surrounding the observatory—“an area larger than the combined landmass of Connecticut and Massachusetts,” Kurczy notes—imposes similar strictures on cell phone and Wi-Fi usage.

Green Bank looked to be an ideal spot for digital refugees to congregate—and so, Kurczy, animated by his own “ideological battle against … constant connectivity,” sets out to live there for a year and plumb the struggle to shore up the foundations of a noise-inhibiting, signal-sparse world. It’s clearly an uphill battle: Even by the time he arrives, Kurczy finds that “the observatory was hosting around thirty media visitors a year and taking more than one hundred press inquiries annually, with a regular stream of articles being published about the Quietest Town in America.” One of the town’s corps of recently transplanted sufferers of electromagnetic hypersensitivity, or EMH—an ill-defined, often self-diagnosed condition of acute allergic-style reactions to electromagnetic waves—soon drew talking-head duty for a battery of documentaries and news reports on the ailment and its treatment. “I walked into Hollywood here,” she tells Kurczy. “Who knew?”

Green Bank’s paradoxical status as the media capital of quietude also poses a narrative challenge for Kurczy: how to break new ground in his immersive experiment in Quiet Zone living? Can the residents in and around Green Bank come across as something other than the dominant motif in all those news reports—colorful and stubborn throwbacks to a simpler way of living and adherents of an uncomplicated face-to-face model of communication among insulated populations separated by great distances? What lessons, if any, are bound up with the uncertain future of the NRAO? Over the past few decades, the observatory had been contending with the specter of increasing federal budget cuts under the stewardship of the National Science Foundation. By 2016, midway through Kurczy’s sojourn in Green Bank, the NSF announced that it could pull its support from the facility—leaving it, like so many other former public-sector research projects, at the far from tender mercies of the market.

Kurczy gamely seeks to wrestle with these issues and to dig beneath such surface impressions of the Quiet Zone. He does unearth some key discoveries—chief among them the revelation that the Quiet Zone’s inhabitants actually do have ample connectivity: Efforts to police cell phone and Wi-Fi usage have atrophied under conjoined fiscal and cultural pressures, so that by the time of his tenure in Green Bank, nearly every home is equipped with Wi-Fi, and only determined holdouts get by without a cell phone. (Kurczy ranks among them, having relinquished his cell phone after a reporting tour in Cambodia in 2009.)

The observatory has decided it can live with a certain incursion on its radio spectrum from the scattered population base in the Quiet Zone—but the region’s growing cohort of EMH refugees registers alarm at the prospect of the encroaching digital world. One of them wrote an appeal to the NSF to continue funding the observatory and policing electromagnetic trespasses against the Quiet Zone: “In a world now filled with overlapping, omnipresent radiofrequency and pulsed microwave technologies, where exactly do you think [EMH sufferers] should go if the Green Bank Observatory were to close? For us, this is not about losing a job or having to move. This is about our very survival.”

But since Kurczy can’t make much either way of the at-times extravagant claims of EMH sufferers, he lets this controversy fizzle out—which largely leaves him with the rather unexceptional narrative of a lagging technological enclave choosing to close the digital divide under its own steam. So the saga of The Quiet Zone soon becomes a catch-all quest for parallel indicators of all manner of psychic and criminal distemper lurking beneath the surface calm of life in Pocahontas County, the broader rural jurisdiction in which Green Bank is nestled.

Kurczy ventures into the mountain compound of the National Alliance, the militant white supremacist hate group founded by William Pierce. Pierce, who died in 2002, is best known as the author of The Turner Diaries—the novel recounting a fantasy vigilante assault on Washington D.C. and the mass lynching of whites in biracial marriages and families. But since Pierce’s death, the National Alliance had relocated its headquarters to Tennessee; what remains of the original West Virginia site is now largely a shrine to Pierce, together with a makeshift library and chemical lab. By the time Kurczy leaves, the remaining hangers-on at the site sell most of it off and fan out to other neo-Nazi frontiers in Trumpian America.

Undaunted, Kurczy unearths several unsolved murders in the region and speculates on their possible resolution. One was a brutal murder, back in 1980, of two young female hitchhikers who’d attended the region’s Rainbow Gathering, a late-hippie wilderness countercultural celebration. A Pocahontas County local, Jacob Beard, had been initially convicted of the crime but was later acquitted when Joseph Paul Franklin, a notorious racist serial killer jailed in Wisconsin, confessed to the crime, claiming that he’d killed the women for engaging in interracial relationships. In Pocahontas County, suspicion continues to swirl around Beard, even though two book-length accounts of the crime conclude Franklin was the killer. Undeterred, Kurczy interviews Beard from his home in Florida to predictably inconclusive effect: “It sounds like you think I’m guilty,” Beard tells Kurczy, and notes once more, “I wasn’t there. I didn’t do it.”

Kurczy also probes a still earlier pair of murders, from 1975, involving a well-known caver from Pennsylvania named Peter Hauser and a West Virginia University student named Walter Smith. Smith’s body was found in a cave near Hauser’s home via a suicide note, and Hauser’s body was found in a nearby wooded area. Kurczy is driven for some reason to go deep into the cave network where Smith’s body was interred—and fantasizes about his local docent, a hapless recovering meth addict, turning on him in the isolated darkness and killing him.

What does all this rural gothic arcana have to do with the Quiet Zone and its slow-motion deterioration under the pressures of modernity? Very nearly nothing, but that doesn’t prevent Kurczy from delivering this creaky, cliché-ridden rationale:

The quiet of Pocahontas had initially sounded so idyllic. Then I started hearing about this darker side … Pocahontas was an area of extremes, and I felt sucked toward its poles. I hadn’t come to the Quiet Zone to investigate decades-old murders, and [Kurczy’s girlfriend] Jenna reminded me that such [sic] was far from my original premise of looking for a place outside the bounds of modern connectivity. But maybe it was all connected, so to speak. With solitude came isolation. With disconnection came the inability to call for help. Perhaps the unsolved killings were a symptom of how justice played out in an ultraquiet place.

Alas, Kurczy’s just getting warmed up as he scours the Pocahontas terrain for anything of remote narrative interest. It so happens that Hunter “Patch” Adams, the celebrity clown doctor who was the subject of the 1998 Robin Williams biopic of the same name, was allegedly building a multimillion-dollar free hospital in the region. It turns out, though, that Adams is mostly based in Illinois, and the structure is still incomplete after more than two decades of fundraising around it. This spurs Kurczy to another predictably inconclusive phone interview with Adams and another rapidly taken-up-and-discarded episode in The Quiet Zone, all prompted by the portentous question, “In the quietest place in America, could one get away with murder and fraud?”

By the time Kurczy does return to the book’s ostensible theme, the clichés are coming fast and furious. He even quotes dialogue from Twin Peaks, David Lynch’s hackneyed-yet-gnomic TV study in rural gothic menace, to suggest “there’s a sort of evil out there. Something very, very strange in these old woods.” Lest this burst of made-for-TV backwoods exoticism somehow seem too subtle, Kurczy dilates on it further, in this disjointed litany of lessons learned:

That’s what discovering the many layers of the Quiet Zone felt like. The vision that drew me in turned out to be a mirage. The Quietest Town in America was full of WiFi and smartphones.... The electrosensitives seemed to be fleeing something in their lives aside from electromagnetic radiation. The free hospital for rural Americans who desperately needed access to health care was a joke.

At the end of his lonesome tour through the Appalachian wilderness, Kurczy interviews one of his erstwhile neighbors, who warns him against indulging in “disconnectivity porn,” in the same way that legions of reporters in the region had adopted a lazy fallback narrative of “poverty porn.” But as The Quiet Zone makes all too plain, the real vice among writers professing to uncover the true character of our rural interior is dark-side porn. If and when some tech entrepreneur develops an effective filter to weed out this exasperating narrative template, I promise to be first in line on release day. It turns out that, regardless of the ultimate disposition of Wi-Fi access in Pocahontas County, there are still some kinds of quiet very much worth fighting for.