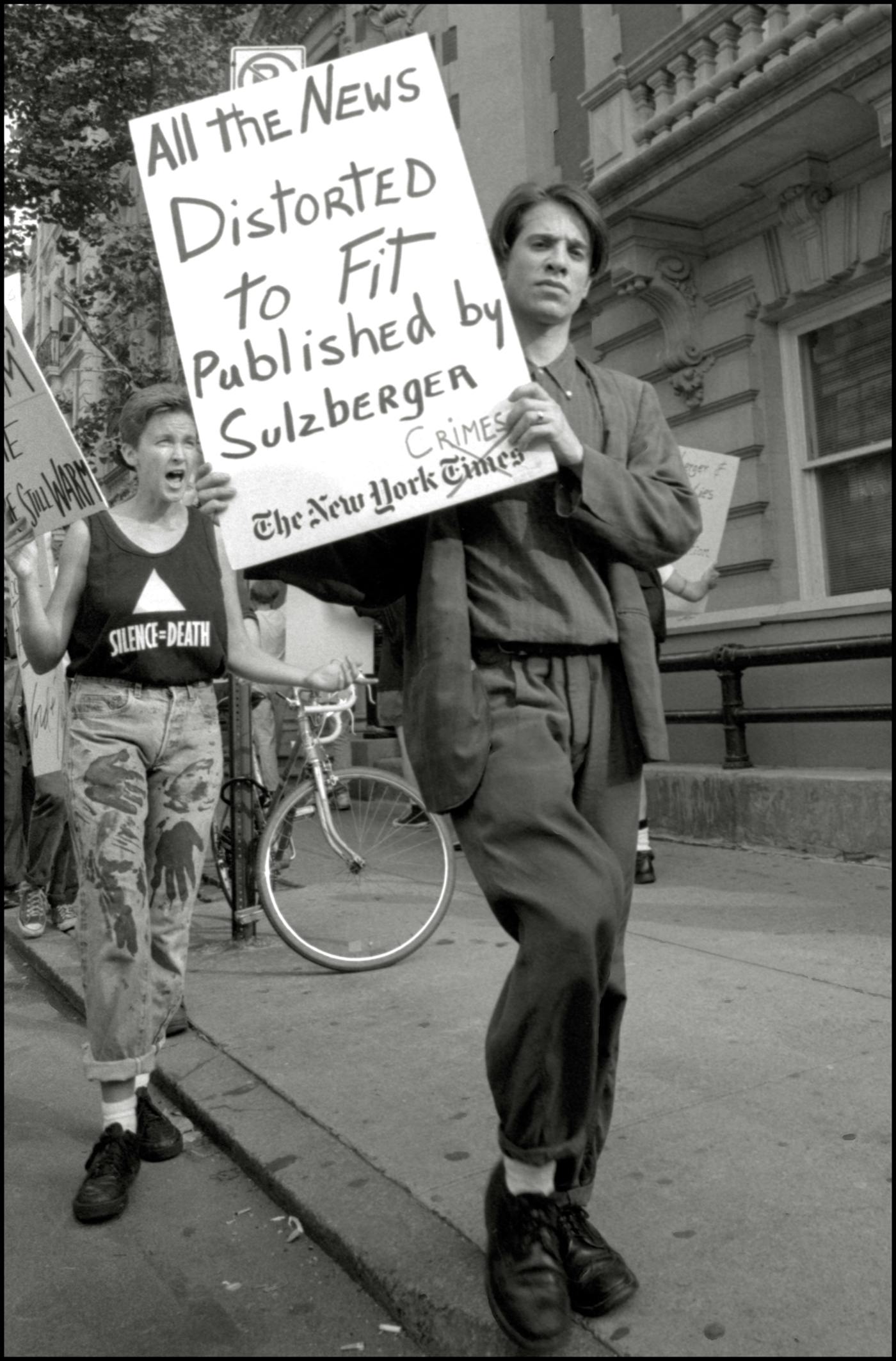

Imagine this: You’re a photo editor at a major newspaper. The year is 1991. Tomorrow, a story about a protest by the activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) is running in the paper, and you must select an image to illustrate it. You’re paid to know newsworthiness when you see it, so you scan the shots of the demonstration for the image most likely to catch your imagined reader’s attention. Which one will you choose?

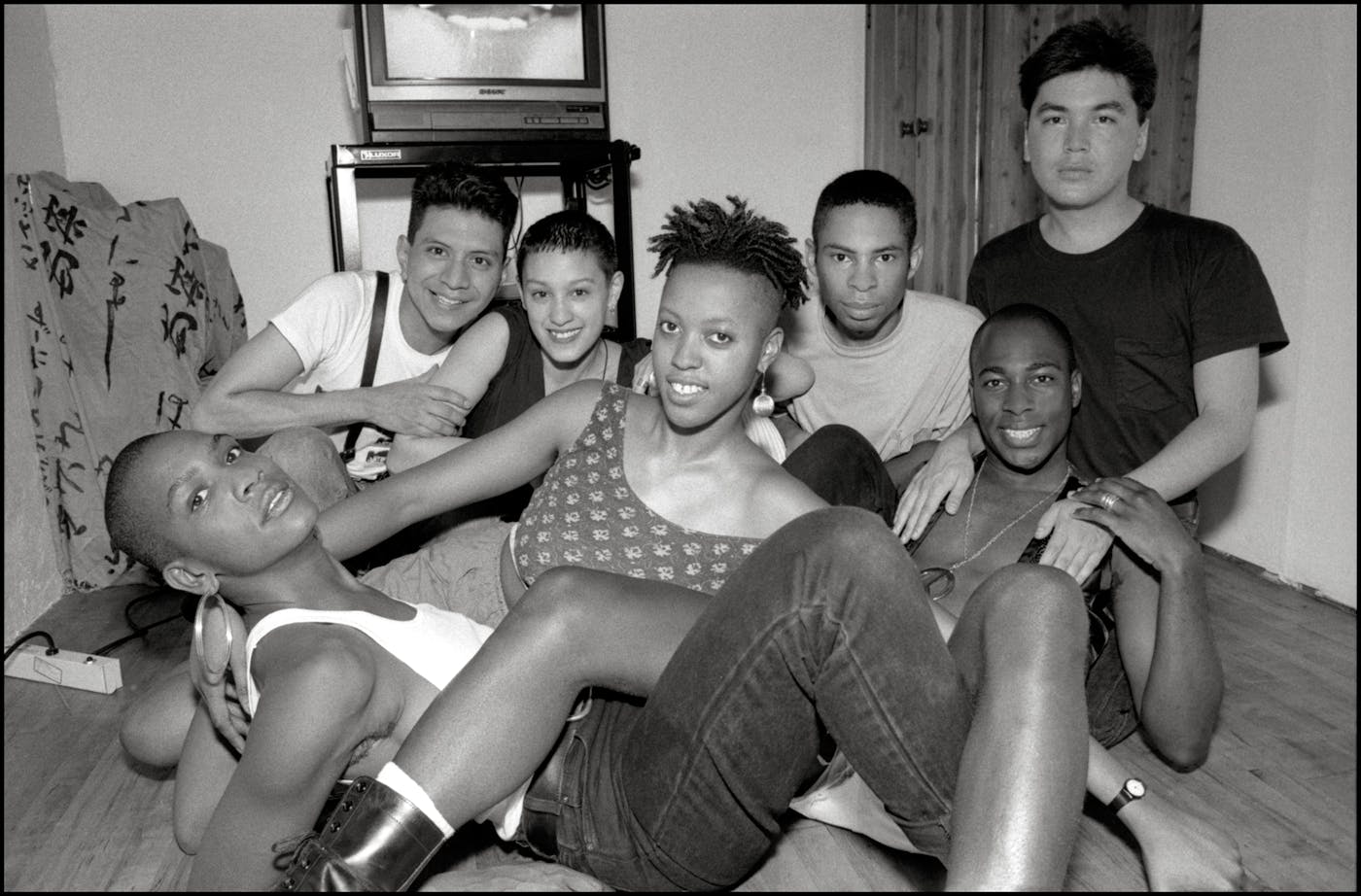

Now, imagine that you’re a teenager in the present day. Your grandmother died of Covid-19, and your anger has made you curious about the history of activist health care politics in the United States. Over the last 30-odd years, however, history has turned into something called “image results,” and your Google search activates a proprietary indexing algorithm skewed heavily toward showing you images from English-language newspaper archives. What appears on your laptop or phone screen as you go in search of the past? Both questions have the same answer: Images of handsome, mostly white young men wearing clean T-shirts printed with legible slogans. This is how misrepresentation hardens into the only history available.

In her new book, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993, Sarah Schulman takes a circuitous route to the truth but ultimately arrives at a devastating precision. For despite what Google Images shows you, ACT UP was a movement built on the foundations of other movements, particularly those for reproductive rights and against institutional racism. Its invocation today could be a foundation for similar movements of the future—if only its style hadn’t been so easily absorbed and commodified by the market.

Schulman is well known as an activist—one of the group who stormed Congress in 1982 to protest an anti-abortion bill, an ACT UPper, and co-founder of the Lesbian Avengers—and as a writer of many genres, including novels and plays. Her 2014 guidebook for resolving conflict without conscripting the use of force, Conflict is Not Abuse, has earned cult classic status. Adapting hundreds of interviews into continuous, quotation-heavy prose, the new book is an continuation of the mammoth ACT UP Oral History Project Schulman began in the early 2000s with Jim Hubbard. In short, she has a kind of credibility in this field that her conservative queer contemporaries like, say, Andrew Sullivan, who in 1999 wrote an abysmally counterfactual cover story about HIV/AIDS for The New York Times Magazine titled “When Plagues End,” do not.

In her words, the “corporate cultural apparatus” has, for a very long time, “favored works—both creative and journalistic—that made straight people into the heroes of the crisis.” There are now two generations, she writes, “whose primary exposure to AIDS comes from … the Oscar winner Philadelphia and the Pulitzer winner Angels in America.” These movies are more often thought of as HIV/AIDS than as works that hurt the cause of HIV/AIDS justice. But Schulman’s critique is deliciously on target: Both stories “show alone and abandoned gay men with AIDS, contrasted with a homophobic straight person who heroically overcomes their prejudices to support the poor gay man who has no community and no political movement to protect him.” It seems natural to add that the number of acclaimed movies about heroic whites fighting AIDS made in the last 10 years, like Dallas Buyers Club, BPM (Beats Per Minute) (which I reviewed positively), The Normal Heart, and so on, is bizarrely high.

From the human perspective, it’s simply satisfying to consume Schulman’s fulsome demonstration that ACT UP was not the work of heroic straights or the clean-cut and mostly white men whose names are now synonymous with the group, such as Larry Kramer, but in fact always relied on the many people of color, incarcerated people, women, and drug users who devoted their labor. It’s a joy to get to know Lei and Kathy Chou, Robert Vazquez-Pacheco, and many, many more. The greater the contrast between ACT UP members, it seems, the greater their success. Dan Keith Williams, for example, enraged many by stealing money from ACT UP, which he never repaid, but also testified while “high as a kite” to the importance of needle exchange in a 1991 trial, which ended with volunteer lawyer Jill Harris making the judge cry with her closing arguments about how drug users also deserve to live.

But from the historian’s perspective, which drifts toward the unpleasant, Schulman and her interviewees’ analysis of how such complex and specific labors came to be erased by the very artworks that brought HIV/AIDS activism to the mainstream is even more fascinating.

“Movements have looks,” Schulman writes, and “most come organically from the people in the streets. But there is also intentionality: Black civil rights workers in suits and ties carrying mass-produced signs written in clean lines proclaiming, I AM A MAN.” By the same token, there is something intentional behind the look and feel of political activism of the 1980s and 1990s currently enjoying a serious revival in fashion, graphic design, and political rhetoric—from conscious members of the street movement for Black lives to tweens selecting the cutest pencil case at Urban Outfitters, and all the suits making money in between.

Avram Finkelstein recollects the origin of one of the key ACT UP designs. An art director for Vidal Sassoon who grew up Jewish in Long Island, in high school Finkelstein made a lithograph of the line, “Sheep, who die silently, are no use as victims.” Then his lover, Don, got sick and ended up in Bellevue, which Schulman notes “had a well-deserved reputation as a snake pit.” Avram formed a design group with the aim of making wheat-paste posters. They “agreed that in order to compete in an urban context during the height of Reaganomics, it had to look slick, to appropriate the voice of authority.” Everybody in the group hated the rainbow flag, which Finkelstein says “was too friendly and, I’m not going to lie, just too ugly.” Although they also hated the pink triangle the Nazis had made gay prisoners wear, they found that by turning it upside down they were “connecting the AIDS crisis visually to the legacy of the Holocaust but at the same time subverting it.” I’d add that it was also chic. Avram proposed the slogan, “Gay Silence is Deafening,” which his friend Oliver tidied up into “Silence Equals Death.” Somebody else came up with the equals sign. “It was literally that fast,” Finkelstein said. “It was four comments.”

There is a declarative, clean aspect to this kind of design that now seems eerily custom-built for the contemporary trade in decontextualized images online. Several people in Let the Record Show mention Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, the artists whose typed works most closely resemble the surreal-meets-bombastic vibe of contemporary internet humor and the activist sloganeering that arguably made it possible.

One extraordinary artwork by the ACT UP collective Gran Fury riffed on its own style, playing on the idea of type size and its relationship to emotion. Schulman quotes Tom Kalin on The Four Questions (1993): “It was a giant sheet of paper, and, printed very small, were these four questions: Do you resent people with AIDS? Do you trust HIV-negatives? Have you given up hope for a cure? When was the last time you cried?” One member of Gran Fury later told Barbara Kruger, “You know, we owed you a lot. And Kruger said, I know, but I’m glad you did.”

Just yesterday, I saw the ACT UP pink triangle and slogan SILENCE=DEATH stenciled on the wall of an edgy, queer teen in the new show Mare of Easttown. An episode on the last season of Pose reenacted the ACT UP Stop the Church action at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan. The triangle-and-slogan design is now so popular that my wife has begun a collection of knock-offs: Her favorite is a pin with a triangle on it, the Nazi way up, with the cheerful slogan ACTION=FUTURE!

There’s a revival going on in fashion, too, a combination of uniforming (work jackets, denim, interchangeable cotton basics, boilersuits) and tough edge (leather, black boots) that is lifted directly from the streets of the late 1980s and ’90s. But there’s also a concomitant feeling that commitment to the cause of liberation for people of all races, genders, and sexualities is in danger of going out of style, proving that political earnestness was just a trend all along. Perhaps the surest sign of the ACT UP cultural revival is the backlash against it: Covid-19 discourse has witnessed a rise in flippancy online, most notoriously congregating around the quarantine “scolds” who condemned people who met up over the 2020 holiday season. The backlash to the scolds seems to be an allergic reaction to buzzwords—particularly around health and safety, and their relationship to social behavior—that have been compromised by a state trying to grapple with a pandemic.

It’s impossible to disentangle HIV/AIDS from the Covid-19 pandemic, because we are still fighting about viruses, social responsibility, and whether people’s behavior makes them “good” or “bad.” Though an activist could call the way we misremember ACT UP whitewashing, a designer might call it simple influence. Together, all these weird conversations form a muddled and compromised revival of the aesthetics of the last time a grassroots organization significantly reformed the U.S. health care sector, in our own era of uncontrolled viral transmission and meaningless mass death. When ACT UP demonstrated at the New York City stock exchange in 1989, for example, a group of activists dressed as traders made it up to the balcony to blast foghorns. Three days later, the price of an expensive pharmaceutical went down by 20 percent—the first and last time such a price drop has ever happened to an HIV/AIDS drug in the U.S. market.

The story of ACT UP and design is much longer than this, and it’s only one among hundreds of threads Schulman takes up in the book. But the knock-off ACTION=FUTURE! button kind of says it all; this work of adapted oral history is a mixture of creative froth and leaden grief, and eerie mismatches between what really happened and what appeared to have happened on the television or in movies or in the news. Gradually, Schulman corrects a view on history that’s been distorted by the profit motive—often computer-automated—that usurps popular visual styles as soon as they are worth copying.

Ephemeral though design values may seem beside urgent medical needs, we can’t understand the recent backlash against the language of inclusion and social justice without understanding how the verbal and visual vocabularies of ACT UP and its associated movements slipped out of the left’s control in the first place.