“Everybody knows that the dice are loaded,” sang Leonard Cohen, who died the day before Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, which he had confidently predicted. “Everybody knows the fight was fixed / The poor stay poor, the rich get rich / That’s how it goes / Everybody knows.” It’s hard to imagine a phrase more evocative of our era. Everybody knows that at least 22 women have accused the president of sexual misconduct, everybody knows that he lies compulsively, and everybody knows that he lacks the basic mental fitness for office. Everybody knows that the president is a racist and a xenophobe who draws fervent support from outright white nationalists. Everybody knows the seas are rising, and everybody knows it’s going to get much worse.

Everybody knows, too, that the grotesque qualities embodied by the president are widespread among the Manhattan elite that tolerated and nurtured him, from the real estate sector to the tabloid press and from NBC to Fox News. Just like everybody knows that Jeffrey Epstein was a pedophile, and everybody knew it when he was hosting VIPs at his Upper East Side mansion and on his private jet. Everybody knows that after his apparent suicide, most of his elite associates will escape any justice. That’s how it goes.

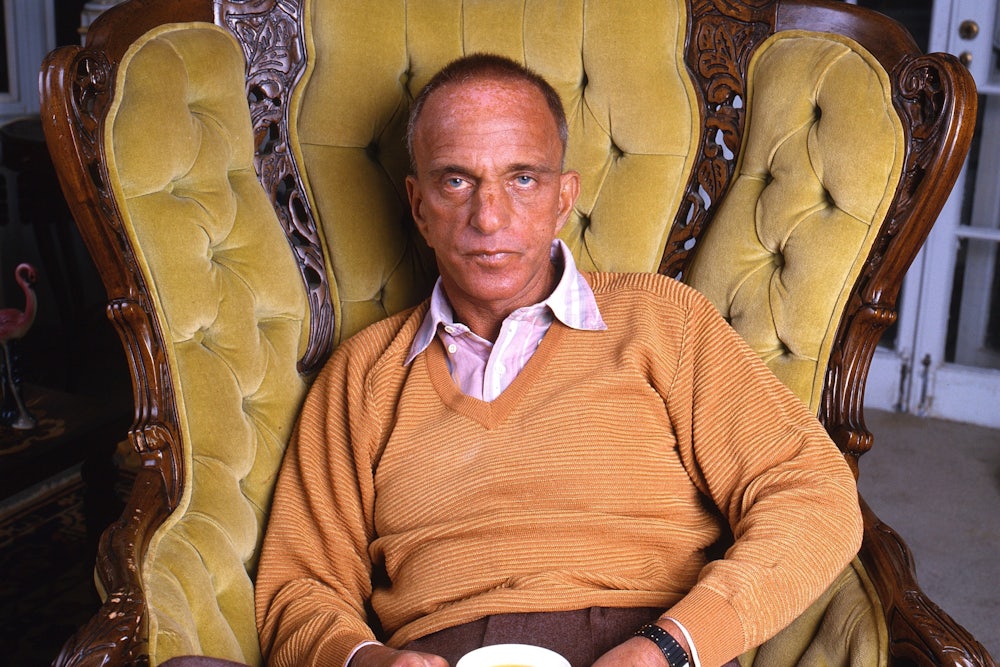

This is the unspoken, and perhaps unintended, takeaway from Matt Tyrnauer’s new documentary, Where’s My Roy Cohn?, whose title is borrowed from Donald Trump’s reported exclamation after finding his then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions insufficiently loyal and ruthless. Tyrnauer, to judge from the quotes that he uses to frame his story, wants to cast Roy Cohn—the crooked New York lawyer whose sordid career was a common thread linking Joe McCarthy, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and eventually Trump—as the personification of evil. The word “evil” comes up a lot, and it certainly fits Cohn, with his dead eyes and manifest lack of empathy or scruples. Cohn, we’re told repeatedly, established the now-familiar playbook for all of the nastiest figures in American public life: Sidestep legitimate inquiries, always go on the offensive, attack the press, demagogue against minorities, make headlines, break laws, win at all costs, and shamelessly taunt the losers. Trump was merely his protégé.

As a portrait of Cohn, the documentary is riveting. In addition to interviewing a wide circle of journalists, associates, and relatives (including Roger Stone, Ken Auletta, Liz Smith, Anne Roiphe, and David Cay Johnston, among many others), Tyrnauer has pieced together material from hundreds of hours of archival footage—which is possible mainly because Cohn possessed a malevolent charisma and was a television fixture for decades. Of course, his ubiquity in the media was facilitated by the particular circles he traveled in.

Cohn was much smarter than Trump, but the two had a few things in common. They were both born in wealthy outer-borough families; Trump inherited a real estate fortune in Queens, while Cohn came from a banking fortune in the Bronx. Nonetheless, they both made awkward fits in the Manhattan elite; Trump because of his obvious vulgarity, Cohn because the Great Depression, which began when he was two years old, shuttered the family business and resulted in the Cohns’ exile from Jewish high society. This forced a young Cohn to make his own way, via law school and then early notoriety as the prosecutor who put Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the electric chair and as the right-hand man to Joe McCarthy, a fellow bachelor and red-baiter. The nationally televised 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings prominently featured Cohn and made him infamous. Subsequently, he made a fortune as a Manhattan lawyer, and became a regular at the best restaurants and clubs. He profited off mob ties and tax evasion until he was eventually disbarred over ethics complaints, shortly before dying in 1986 of what he insisted was “liver cancer.”

Of course, as immortalized in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, everybody knows that Roy Cohn actually died of AIDS. Everybody knows he was gay, that he supposedly had to have sex daily (as has similarly been observed of Epstein), and that he surrounded himself throughout his life with young, handsome, distinctively goyish-looking men (one of whom agreed to be interviewed for the film). Everybody knows he was partying at Studio 54 and bringing home strangers every night. Everybody knows he used his connections in the White House to get special access to experimental treatments at NIH, even as the Reagan Administration publicly ignored the AIDS epidemic (and its allies in the religious right practically cheered it on). Everybody knew Cohn was gay as early as the McCarthy era; Tyrnauer’s film establishes that the Army-McCarthy hearings carried a powerful gay subtext, and that the instigating event was Cohn’s leveraging of the Red Scare to secure special treatment for his probable lover David Schine, who had just been drafted into the Army. A rare moment of sympathy for Cohn comes when the Army’s lawyers openly gay-bait him on TV.

It’s clear from the archival footage that everybody knew all of this. Journalists typically referred to Cohn as “flamboyant,” and the word appeared in the first line of his New York Times obituary. Gore Vidal teased Cohn about it to his face on a talk show in 1977; Ken Auletta asked him about it point blank in an interview, as did Mike Wallace as Cohn was facing death. Cohn never exactly denied it; instead, with characteristic cynical humor, he would say that anyone who knew him and recognized him as a tough, aggressive guy would have a hard time reconciling that with his alleged homosexuality. Everybody knew, and Cohn knew everybody knew, and that’s how it went.

Everybody knew that Cohn was dictating newspaper coverage to credulous stenographers at the major New York tabloids for years—Roger Stone, who learned the art of ratfucking from Cohn, recalls this with clear admiration in the documentary. Everybody knew that Cohn was connected to the most powerful mobsters in New York, and that thanks to him, John Gotti was able to get away with a two-year sentence for murder. Everybody knew that Cohn’s reputation in the courtroom was the source of his social power; after he was finally disbarred over his egregious legal ethics, he lost most of his friends, including the ever-fickle Trump.

In addition to defending mob murderers and championing the death penalty for communists and cop-killers, Cohn may have had a more direct role in killing at least one person: a crew member on his generously insured yacht (although, ever the lawyer, he would insist that technically it was not his yacht) who died in a mysterious fire in 1973. The crew member’s father was among the many who suspected foul play. It’s unclear whether everybody knew this, but a lot of people did.

Everybody, it seems, knew Roy Cohn: Barbara Walters, Aristotle Onassis, George Steinbrenner, Andy Warhol, William F. Buckley Jr., mayors and governors and presidents and white-shoe lawyers and mob bosses. As long as he had his money and his health, he could move freely about Manhattan society—showing off beautiful women he had no interest in, sexual or otherwise, as decorations; hosting clients in his home office clad in his bathrobe, in front of his collection of stuffed frogs; readily supplying eager journalists with quotes embracing his Machiavellian reputation; sabotaging politicians with salacious rumors and gleefully taking credit for the results.

Everyone, including Tyrnauer’s interviewees, knew he was a monster, but this doesn’t seem to have prevented them from socializing with him. They call Cohn evil, immoral, a self-hating Jew, a hypocrite, and worse, and they want to make sure history records him as such, but it’s pretty clear they also found him mesmerizing company. And this is the problem when Everybody Knows. Why did it take 30 years to disbar Cohn over ethics violations happening in plain sight the whole time? Why did journalists keep putting this shameless crook on TV? Why didn’t mob ties disqualify him from high society?

Most likely, because our entire culture is obsessed with charismatic sociopaths. We invite them to our parties, we root for them on prestige dramas and reality TV shows, and we’ve (sort of) elected one of them to be the leader of the free world, and by extension the protagonist of our national story. It’s all well and good to call Roy Cohn evil, but the movie is still about him, isn’t it? It’s still his face we see in frame after frame, his voice we hear taunting us again and again, his crimes and his legacy that obsess us, his parents and troubled childhood that invite speculation. In one interview, Cohn says every bad thing anyone said about him was good for bringing in business, and it’s hard to see why this documentary would have struck him any different.

Performing evil works because our institutions are designed to reward it. Cohn’s evil was extremely lucrative, and even though it eventually caught up with him, the presence of a Cohn disciple in the Oval Office is one hell of a last laugh. Tyrnauer wants to indict Cohn and the politicians and media elites who follow his example, and he has all the material he needs to succeed, but he stops short of fully indicting the environment that produced Cohn. Structural evil is a lot harder to capture on film; it’s rarely so flamboyant.