The Supreme Court appears poised to uphold two voting restrictions from Arizona in a challenge brought by Democrats under the Voting Rights Act. In oral arguments on Tuesday, the court’s six conservative justices seemed ready to make it harder to bring a claim under the Voting Rights Act provision in question—though just how high they might set the threshold, and how much voter suppression could slip away under it, remains unclear.

Tuesday’s oral arguments did not occur in a vacuum. In Congress, federal lawmakers are debating H.R. 1, a sweeping set of election reforms put forward by Democrats to make it easier for Americans to vote. At the same time, in state legislatures around the country, Republican legislators are introducing a cornucopia of bills that would make it harder to vote, drawing upon the “Big Lie” about voter fraud in the 2020 election. How the Supreme Court decides this case could influence legal challenges to election laws for decades to come.

The cases, Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee and Arizona Republican Party v. Democratic National Committee, center on two provisions in the Grand Canyon State. One of them is an Arizona law passed in 2016 that banned almost all third parties from collecting absentee ballots; the other is a state policy that threw out otherwise lawful votes if they were cast in the wrong precinct. The DNC argued that both measures violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which generally forbids states from passing voting laws that would “result in a denial or abridgment of the right to vote on account of race.”

When does a voting restriction fall afoul of Section 2? That’s where the parties disagree. To the DNC, the two Arizona provisions violated the VRA by disproportionately affecting Black, Hispanic, and Native Americans. It pointed to evidence presented in the lower courts that minority voters were twice as likely to have their vote tossed out by the out-of-precinct policy, as well as analyses that found Hispanic and Native American voters would be disproportionately affected by the ballot-collection ban because they had less reliable mail service in the first place.

Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, a Republican, told the court on Tuesday that he wanted a more “substantial” burden of proof for Section 2 claims. In briefs filed before the court, he had suggested that some of the evidence offered by Democrats was insufficient at best. He also defended both measures on the merits. “They are also commonsense and commonplace,” Brnovich said on Tuesday. “Requiring in-person voters to cast their ballots at assigned precincts ensures that they can vote in local races and helps officials monitor for fraud. Restricting early ballot collections by third parties, including political operatives, protects against voter coercion and preserves ballot secrecy.”

That view seemed to appeal to the court’s conservative justices. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh each favorably referenced a 2005 report by a bipartisan commission that found an elevated risk of fraud with ballot collection, though a lawyer for Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs noted that no such fraud had been found in Arizona’s elections. Justice Samuel Alito suggested that the DNC’s broader interpretation of Section 2 would “make every voting rule vulnerable to attack.”

However, there did not appear to be a majority of justices in favor of the nearly insurmountable threshold proposed by Michael Carvin, who argued on behalf of the Arizona GOP. Carvin told the justices that Arizona had not denied any of its voters the opportunity to cast a ballot, adopting a narrow interpretation of Section 2 that gained little traction even among the court’s conservatives. “I think the key conceptual point here to understand is that Arizona has not denied anyone any voting opportunity of any kind,” he told the justices. “There’s not, like, a literacy test which denies you the right to vote.”

Justice Elena Kagan used her time to pose a series of hypothetical questions to Carvin. “A state has long had two weeks of early voting, and then the state decides that it’s going to get rid of Sunday voting on those two weeks [and] leave everything else in place,” she said. “Black voters vote on Sunday 10 times more than white voters. Is that system equally open?” Kagan’s example is timely: Georgia’s lawmakers are considering such a move right now. Carvin insisted that it would pass constitutional muster, on the grounds that state governments have a long tradition of closing on Sundays.

“Can we go—just go on to another one?” Kagan continued. “The state says we’re placing all our polling places at country clubs. And that decision means that Black voters have to drive 10 times as long to the polls and have to go into places which, you know, are traditionally hostile to them.” Carvin conceded that such a move “would provide them with less opportunity than nonminorities.” This was a substantial retreat for Carvin, who had argued in his brief before oral arguments that states were generally free to regulate the “time, manner, and place” of elections, a view of Section 2 that drew sharp questions from even Chief Justice John Roberts.

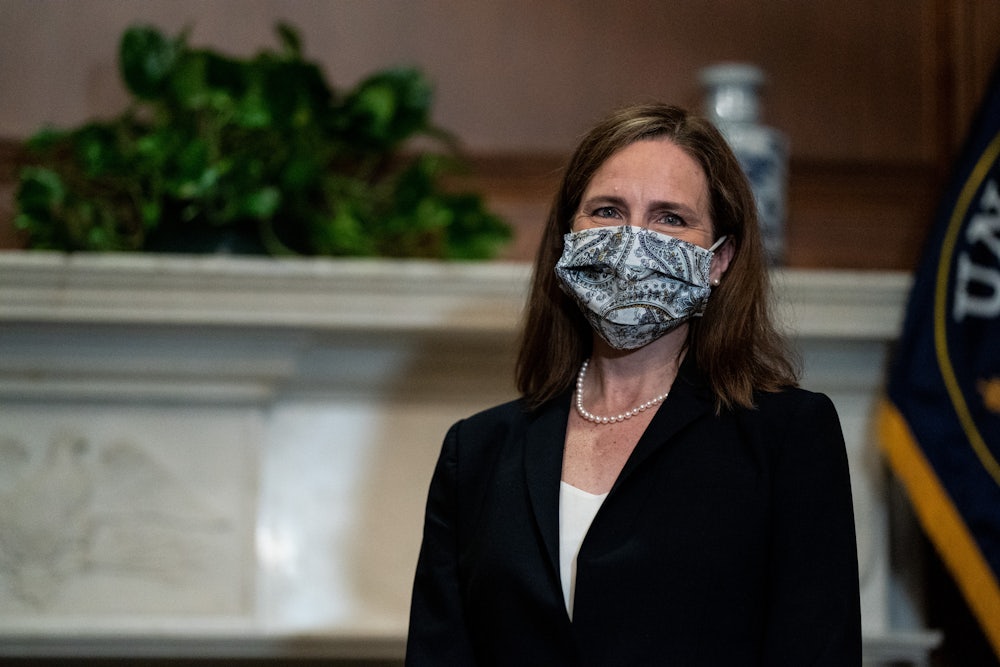

But the most damning question for the Arizona GOP came from Justice Amy Coney Barrett. She noted that the DNC had legal standing to participate in the case because the out-of-precinct policy it challenged could make it harder for the party’s supporters to cast a ballot. But that theory doesn’t apply to the Arizona Republican Party, which is arguing in favor of the restrictions. “What’s the interest of the Arizona RNC here in keeping, say, the out-of-precinct voter ballot disqualification rules on the books?” Barrett said.

“Because it puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats,” Carvin replied. “Politics is a zero-sum game, and every extra vote they get through unlawful interpretations of Section 2 hurts us. It’s the difference between winning an election 50 to 49 and losing an election 51 to 50.” Carvin made a similar point in his pre-arguments brief, warning the justices that “court-ordered overhauls of state voting rules to achieve racial proportionality” would be “a boon to one political party, to be sure,” referring to Democrats. It was a striking admission of raw gamesmanship that, in another age, might have made the lawyer blanch before offering it to the Supreme Court.

But in this particular case, this might have been unavoidable. Voting rights cases are more often brought by civil rights groups on behalf of voters, not the political parties themselves. But the case titles themselves underscore the partisan valence of this dispute. With the Republican Party all but abandoning policymaking and basic governance in favor of culture-war spats and voter suppression, the defining factor in American elections could be whether GOP state lawmakers succeed in cutting off enough legitimate paths to the ballot box to secure their victory in advance.

Beyond the hyperpartisan clashes, Justice Sonia Sotomayor highlighted at one point what was really at stake. “If you can’t vote because you are a Native American or a non-Hispanic in areas where car ownership rates are very small,” she asked Carvin, “where you don’t have mail pickup or mail delivery, where your post office is at the edge of town and so that you require either a relative to pick up your vote, or you happen to vote in a wrong precinct because your particular area has a confusion of precinct assignments, if you just can’t vote for those reasons, and your vote is not being counted, you’ve been denied the right to vote, haven’t you?” That so many Republican-controlled states are indifferent to this problem speaks to how confident they are that the court’s majority won’t stop them.