The proceedings began with three fast, muted raps on the door. Layleen Cubilette-Polanco’s family and friends, joined by many, many people who’d never even met her, filled every row in the small, mostly beige hearing room on the third floor of the federal courthouse, somewhere between downtown Brooklyn and the waterfront. Five months before, on June 7, 2019, Layleen, a young transgender woman, died while she was held on $500 bail in New York City’s despised jail complex on Rikers Island.

It was the first hearing in a suit Layleen’s mother, Arecelis Polanco, brought against the city of New York, charging that the jailers at Rikers had been negligent and bore responsibility for her death. The city’s lawyers were trying to bring the suit to a halt, pending their own investigation. For now, the family’s quest to establish some accountability in Layleen’s death had become the sort of dry, procedural, slow-moving, and official matter that does not inspire headlines.

As a result, nothing in the court that day would address the circumstances surrounding Layleen’s death. The judge would not consider how Layleen was put into so-called restrictive housing (known familiarly as solitary confinement) as corrections officers do to many transgender people who are incarcerated, and so was in isolation in the days leading up to her death. There would be no discussion of how she was jailed because she did not have $500 for bail, or that she was only there because she had once been arrested for prostitution and didn’t complete the city’s program to divert people out of sex work. No one would ask how, in a city where trans women are arrested at a far greater rate than their cis counterparts for doing sex work, or for even appearing to do sex work, these arrests functioned as expressions of a low-level moral panic in the face of a more visible trans community. They’re akin to Michael Bloomberg’s stop-and-frisk regime in the New York subways and streets, in both execution and intent—an all but official sanction of police profiling for the offense of walking while trans.

Sweeping past the cloudless sky framed in the courtroom window, just before half past 10, Magistrate Judge Sanket J. Bulsara took his seat. He would only have to look slightly down from the bench into the front row of observers to see Layleen’s face, her eyes closed serenely, tattooed on her sister Melania’s forearm. Everyone else in the room sat silent, too. Corrections officers and the city officials they answer to had neglected Layleen in Rikers, her family wanted to argue, and now it looked as if they were going to neglect her again: a shocking death, compounded by airless civil proceedings.

This was the de facto bargain the plaintiffs had to strike in taking a case like Layleen’s to court. If you can fit the thing that harmed you—discrimination, abuse, violence—into the room, you can try to make the court see you. If, on the other hand, the social forces assembled in that courtroom can’t read you as someone to whom they owe justice, whatever arguments you came prepared to make won’t matter. At best, they will be caught in the stagnant air, for someone else to try, maybe later and somewhere else.

As more courts ruled over the past decade that same-sex couples could marry, a handful of sanguine liberal commentators rushed to declare the end of the modern culture wars. But even in the wake of that undeniably resounding defeat, the leaders of the Christian right were busy rolling out a more pronounced pivot. And with the new crusade—against a more stigmatized group, only recently gaining political recognition—came a renewed sense of energy and purpose.

Specifically, legal strategists on the religious right seized on the gaps in trans equality as fuel for a new round of confrontations in the courts—elevating on their larger “values” agenda a landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court, R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which came up for oral arguments alongside two other cases this past October, each concerning sex discrimination against gay or trans people.

But to understand how the Harris Funeral Homes case got before the high court, we need first to grasp the depressing degree to which the “T” in the still-evolving “LGBTQ” formulation remains in many ways a legal and political afterthought. Just one year before the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, legalizing same-sex marriage in the United States, Time magazine proclaimed the sudden arrival of “The Transgender Tipping Point.” Actress and advocate Laverne Cox posed next to the empty space where a subhead she had nothing to do with elaborated, “America’s next civil rights frontier.” About that tipping point: During President Barack Obama’s remarks at a 2015 Pride event at the White House, activist Jennicet Gutiérrez briefly interrupted him, making the demand, “release all LGBTQ immigrants from detention and stop all deportations.” This same demand has become both more urgent and more frequently voiced now that Trump has the keys. Yet that day, 19-year-old Gutiérrez, who is trans and an immigrant, was shouted down by some of the invited Pride guests. “Shame on you!” and “This is not for you! This is for all of us!” they yelled—as Gutiérrez repeated, “Not one more!” and “I am a transgender woman,” and the president responded, “Can we remove this person?” and, “Shame on you.” That was one day before the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell.

In such acts of public omission, the Christian right saw the makings of a new legal stratagem, one that might confidently single out the most marginalized figures in the LGBTQ coalition, pitting their fight for equal rights and due-process protections against allegedly religious-based discrimination. Under the aspirational LGBTQ acronym-as-community umbrella, trans people remain less protected than the others. In a way, the decision in Obergefell reinforced this gap—marriage equality became a shorthand for having achieved equal rights, the culmination of the movement for gay rights. Infamously, after the Supreme Court ruling, the 25-year-old advocacy group Empire State Pride Agenda declared victory and closed up shop. Meanwhile, New York state’s anti-discrimination law, which protected people from discrimination based on sexual orientation, did not include gender identity, and it wouldn’t until 2019. In fact, to pass those anti-discrimination protections for gay, lesbian, and bisexual New Yorkers in 2003, Empire State Pride chose to exclude gender identity—leaving trans people out in the cold, again.

Again. This is the story of what was known as “gay rights” in the United States: Even as the name adjusted to at least alphabetically include all LGBTQ people, in practice the rights movement still focused mostly on people for whom discrimination based on their sexual orientation was primary. “The movement,” too, had already begun to fall away, as rights groups professionalized and consolidated influence—a familiar saga institutionalized in the annals of grassroots movements. Yes, Vice President Joe Biden decided to go public with his support for same-sex marriage after a now-famous meeting orchestrated by Chad Griffin, who shortly before had become president of the most mainstream national gay rights organization, Human Rights Campaign—also, this meeting was at the home of an HBO executive and his husband, and it was a fundraiser. This ready-made embrace of marriage equality from on high portended how Obergefell could become a talismanic victory—#LoveWins—in a long-standing legal struggle, even as so many other fights no less rooted in questions of the law’s capacity to see us, and to see us as more than spouses-in-waiting, were left unfinished.

During that same marriage-equality spring of 2015, in Michigan, Aimee Stephens, a funeral director, was in the midst of her own fight, taking on her former employer, Thomas Rost, and his family business, R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes, with support from the American Civil Liberties Union. In 2013, Rost had fired Stephens after she’d stated her intention to present as a woman at work for the first time. The Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission took on Stephens’s case, alleging Rost had engaged in sex discrimination, a violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In May 2015, a few days after oral arguments in Obergefell, an attorney with Alliance Defending Freedom, the “Christian legal army” designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, filed to join Rost’s defense.

ADF formed as a Christian right response to the ACLU. The group is now an anti-LGBTQ powerhouse. “Twenty-five years after its formal launch, the not-for-profit ADF boasts a role in 54 Supreme Court victories,” writes journalist Sarah Posner, “a $55 million annual budget, and more than 60 staff attorneys.” In anti-discrimination cases, ADF leaders see an opportunity to flex their considerable resources; as Alan Sears, one of the group’s co-founders, has written, ADF is dedicated to defeating “radical homosexual activists and their allies [who] are looking for any opportunity to attack and silence any church that takes a biblical stand with regard to homosexual behavior.”

The federal court in Michigan’s eastern district, which first heard Stephens’s suit, ruled that when her employer fired her for being trans—which Rost hadn’t even disputed in the case—he had engaged in sex discrimination. But the court also found that Rost was allowed to fire Stephens under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act—a defense ADF had used in the 2018 Masterpiece Cakeshop case (which litigated the refusal by an evangelical-run bakery to prepare a wedding cake for a gay couple). The following year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit rejected that religious exception in Stephens’s case. As for the sex discrimination claim, their unanimous opinion stated, “it is analytically impossible to fire an employee based on that employee’s status as a transgender person without being motivated, at least in part, by the employee’s sex.”

Rost and his ADF attorneys petitioned the Supreme Court to take up the case—and the court accepted, hearing arguments in Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC last October. It marked the first major LGBTQ rights case of the Trump administration, and it was on the docket for the second day of Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s tenure on the court. On the same day, the court would also hear two additional Title VII cases, both concerning gay men who were fired and who charged their employers with sex discrimination, Altitude Express Inc. v. Zarda and Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia.

“These are the single most important set of explicitly LGBT cases to ever reach the Supreme Court,” Chase Strangio, a staff attorney at the ACLU, and part of the team representing Aimee Stephens, told me before October’s oral arguments. “More than Lawrence [v. Texas], more than Obergefell, more than Masterpiece,” he added. Aimee Stephens would be at the center of the first trans civil rights case the Supreme Court had ever heard. But in the weeks leading up to the arguments before the court, Strangio worried that, in contrast to Obergefell, no one would be paying attention to this case.

“Layleen was just 27-years-old when she died on June 7, 2019 at the Rose M. Singer Center on Rikers Island,” the complaint filed by her mother’s attorneys begins. “She should be alive today.” The Polanco family charges that the city and its jail workers violated the Americans With Disabilities Act and the Fourteenth Amendment. They aren’t claiming that the city and corrections officers treated Polanco differently. To prevail in her case, they need not convince the court to see her as a transgender woman, but to recognize that—as in Obergefell—the state deprived her of her rights. In truth, the two acts are inseparable from each other: The reason the state violates the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer people, as well as the rights of transgender and nonbinary people, is because the state fails to see them as people who have rights to be recognized and defended.

The court was made to understand in Obergefell that it was not only considering the borders of marriage and who belonged within its charmed circle, but also determining who belonged, period. Opponents understood these stakes quite clearly. They were not merely out to defend the sanctity of one veil and one tux only on each buttercream cake top, but the broader, embattled ideal of men’s dominion over women—and with it, decent, law-abiding white Christendom. They were not going to get lost in the thickets of arguments over the original meaning of a Reconstruction-era constitutional amendment when they could opine on the allegedly natural order of things. Yet these things are never about the law, but rather an ongoing battle over everything that can’t fit on the page. Both defenders of equal rights and their opponents know this, even if it cannot be voiced directly in a court of law.

The Title VII cases raise another contested site of critical social and legal recognition—the world of work. No matter how many more LGBTQ people stood to gain from the present set of employment discrimination cases than from marriage equality, the category of workplace discrimination did not fall as easily into a simple narrative. Workers were the protagonists here, not hopeful husbands and wives. The #LoveIsLove frame would not cross this particular threshold; straight allies did not wash their social media avatars in rainbows with the banner #WorkIsWork. While not everyone needs city hall to give them a marriage license, almost all of us have to work for a living. Had the mainstream LGBTQ rights movement dedicated itself to economic justice and labor issues as firmly as it had to granting legal recognition to romantic relationships, maybe the community and the broader public would more readily empathize and understand the significance of economic equity for the movement’s rank and file.

“Obviously, capitalism and legal systems are designed to pit us apart,” Strangio said one month before oral arguments, when I offered a version of the above as my guess for why the cases had not caught the marriage fire. “That’s another way the law, especially formal equality structures, are sort of designed to make people fragmented.”

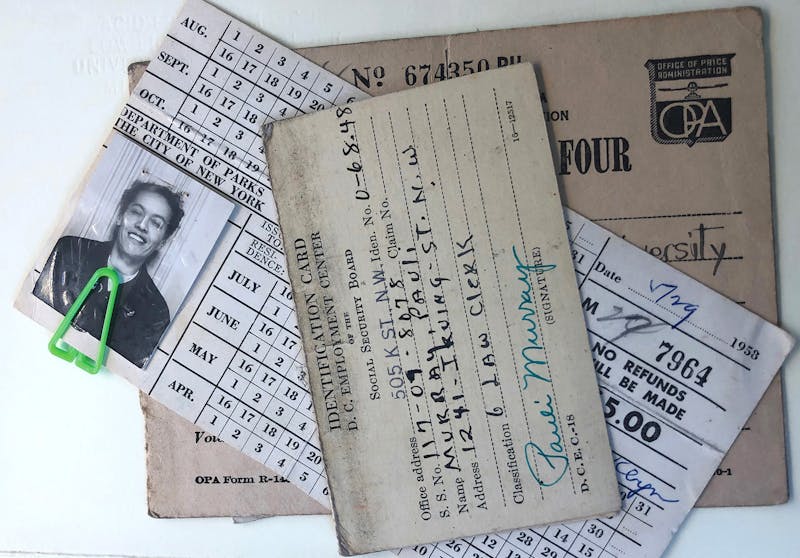

Several decades before Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality was popularized to describe the ways the law failed to recognize overlapping categories of discrimination based on race and gender, a deeply influential but lesser known legal theorist offered another way to understand the dual experience of discrimination for being black and being female: Jane Crow. This was the coinage of Pauli Murray, “who had often spoken of the twin immoralities of ‘Jim and Jane Crow,’” legal historian Serena Mayeri writes. Murray “theorized black women’s singular experience in language that anticipated the concept Crenshaw would term ‘intersectionality’ a quarter-century later.” Murray’s most well-known paper on this legal analysis, titled “Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII,” was published in 1965, one year after the Civil Rights Act became law.

Back in the spring of 1964, as Congress debated the scope of the Civil Rights Act, Murray encouraged the lawmakers to take into consideration the legal analysis of race and sex she had been developing over two decades; she was then a senior fellow at Yale Law School and a member of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Commission on the Status of Women. She sought to intervene when a Senate version of the civil rights bill did not include sex discrimination. Murray drafted her own legislative memo, enumerating why sex and race discrimination must both be included. “It appears that the Administration is something less than enthusiastic about this issue,” she wrote to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, enclosing the memo. (Civil rights attorney Sam Ames surfaced Murray’s Title VII correspondence in a 2019 essay—Murray had sent the memo to Lady Bird Johnson, the first lady, as well, and received a warm note in return.)

“Having somewhat more than a speaking acquaintance with both Jim Crow and Jane Crow, it seems to be my lot in life to make the connection,” Murray wrote to Michigan Democratic Representative Martha Griffiths. Through her efforts and with Johnson’s signature in 1964, Murray’s suggestions became law, a mirror to herself. Later that decade, corresponding with another co-founder of the National Organization for Women (Murray pitched it to Betty Friedan as an NAACP for women), Murray wrote of her “inability to be fragmented into Negro at one time, woman at another, or worker at another.”

Murray first advanced the Jane Crow framing in the early 1940s, while a law student at Howard University. She had been raised in North Carolina, under segregation. Over Easter weekend in 1940, on a Greyhound bus bound for her aunt’s home in Durham, Murray and her companion refused to move as more passengers boarded, shifting the color line dividing the front from the back of the carriage. “Jim Crow’s seating plan lacked place cards,” as historian Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore writes in her book charting resistance to Southern white supremacy in the first decades of the twentieth century, Defying Dixie. It is not clear how planned Murray’s arrest was, but it became an act of civil disobedience. She said she had been reading a book about Gandhi and nonviolence at the time, so she applied it to her situation.

In Petersburg, Virginia, Murray and her companion were taken off the bus. Harold Garfinkel, a white writer for the African American magazine Opportunity, observed the arrests. In his account, he saw “a young colored girl”—Adelene “Mac” McBean, Murray’s companion, who has also been described by others as her lover—accompanied by a “young man” who was “self-conscious in voice and manner. He carried with him a pile of books.”

To write about Pauli Murray means choosing a pronoun that may not be correct. Her archives leave enough of her life behind for some historians to describe Murray at some times as transgender, and at others as a lesbian. (Her diaries and letters, quoted here, can be found at the Schlesinger Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts.) Neither of those identities fits easily. Murray wrote, privately, of her “greatest attraction” to “extremely feminine and heterosexual women.” She also wrote that she was not a lesbian, because she was attracted to women as a man would be, not as a woman.

Murray also left behind a record of her struggle with doctors, searching for some medical basis for what she experienced. Historian Rosalind Rosenberg, in her biography of Pauli Murray, Jane Crow, reconstructs Murray’s exploration, through her archive at the New York Public Library and diary entries from the mid-1930s. Murray had consulted the sexological literature of the day, like the works of Magnus Hirschfeld, a German-Jewish physician in Weimar Berlin, who used the term “sexual transitions” to describe people who may now be described as gay or transgender, all of which made him a target for the Nazi Party. Rosenberg says Murray found the work of Havelock Ellis most helpful. He was a British sexologist who proposed the concept of “sexual inversion” (describing both homosexuals and transgender people). “She wondered why someone who believed she was internally male could not become more so by taking male hormones.” Once, while hitchhiking “in the male attire she favored whenever she was not at work,” police picked her up, and she ended up in New York’s Bellevue Hospital. “There, Murray poured out her story to a psychiatrist, who gave her a diagnosis of ‘schizophrenia.’ In the doctor’s view, she suffered from a delusion: she believed that she was a man.”

“This little ‘boy-girl’ personality as you jokingly call it,” Murray wrote to her aunt, struggling with gossip about her sexuality while at Howard Law School, and its impact on her mental health, “sometimes gets me into trouble … but where you and a few people understand, the world does not accept my pattern of life. And to try to live by society’s standards always causes me such inner conflict that at times it’s almost unbearable…. This conflict rises up to knock me down at every apex I reach in my career and because the laws of society do not protect me I’m exposed to any enemy or person who may or may not want to hurt me.”

The only consensus among historians is this: Murray did not have the same words and frameworks available to her when she was alive as scholars and activists do today. It feels inaccurate to say we can never know Pauli Murray’s gender identity or sexual orientation. It also feels like an imposition on someone so insistent on the dignified multiplicity of her own identity, which—for the present moment—must also contain some features that are unknowable.

At the time of her pivotal arrest in 1940, when Garfinkel identified her as a boy, he also claimed to have heard her give her name to the officer as “Oliver Fleming.” He could have been mistaken about the name—she was later booked under her own at the jail, where she and Mac were housed with women. As she recalled in the late 1960s, “Our fellow prisoners were prostitutes and Negroes who’d been picked up for drinking, and getting into fights, and all of the various things that happen in a small town on a weekend.”

In her cell, in a letter, she vowed she would “go all the way to and from the Supreme Court and back again, if necessary.” Her friends told her Thurgood Marshall—then the head of the NAACP—put two of the group’s “best lawyers” on her case, and she and Mac were invited to meet with the NAACP legal team, including Marshall, to confer on a brief in the case. The Carolina Times, a leading African American newspaper, covered the incident. “Perhaps Miss Murray and Miss McBean are the beginning of a new type of leadership for the race,” writes the paper’s editor and publisher, Louis Austin, “a leadership that will not cringe and crawl on its belly merely because it happens to be faced with prison bars in its fight for the right.” In the end, because the charges the two were ultimately convicted on did not include the state’s segregation statutes, the NAACP didn’t consider Murray’s case strong enough to use in a broader challenge.

Murray and Marshall’s connection would endure, though. In the 1950s, not yet a Supreme Court justice himself, Marshall was preparing the NAACP brief in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 ruling on school segregation. Also on the team was Murray’s former Howard Law professor, Spottswood Robinson. Murray didn’t know at the time, but Robinson pulled a line of argument from one of her senior seminar papers on Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court decision that established the ill-described principle of “separate but equal” as a legal basis for Jim Crow.

When Murray made the case at Howard in 1944 that segregation could be struck down as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, her classmates laughed her off, writes Rosalind Rosenberg. “At a time when litigators believed that the most they could achieve was to make segregated facilities more equal, her proposal seemed radical, even reckless.” Murray bet Robinson $10 that Plessy would be overturned within 25 years.

By the day it was struck down—with the decision in Brown on May 17, 1954—Murray had moved to Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. “Glory be!” she wrote in her journal. She and her old friend from organizing with the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, Maida Springer Kemp, “drank a toast to Mr. Justice Harlan” and then together “went to see [screenwriter] Colette [Audry]’s Pit of Loneliness.” The New York Times review for the film that April noted it took on “a faintly purplish hue because of the secret affections that pass among the teachers and the girls.… Although it skirts along the edges of an area of unnatural love confined within the delicate environment of a fashionable French finishing school, there is nothing indecorous or offensive in the picture as it is played.”

Aimee Stephens was raised in North Carolina, too. She first started putting some distance between herself and her family of origin when she left to study to become a minister, enrolling at Mars Hill University and graduating in 1984. Mars Hill was a small mountain town, about 250 miles from where she grew up, she told me when we met in Washington, D.C., on October 7, the evening before oral arguments at the Supreme Court in her case. The next day, Stephens would be making some remarks on the court’s marble steps, where the press and supporters and the anticipated counterdemonstrators would gather. “In the churches I pastored, I never did sermons ahead of time,” she said. “We were taught in school to learn to speak extemporaneously, so whenever it’s time to speak, I get up to speak.”

Six years have now passed since the summer when she told her boss at the funeral home, Tom Rost, that after a vacation she would return to work as Aimee. She remembered having an awareness at age five, in 1965, that there was something different about her, but she would wait many more years to express this. She was in her fifties when she first decided to go out in public as a woman, about a year before she came out to her boss. She hadn’t really experienced discrimination as a transgender woman, she told me, until it became an issue at work.

Her employment at the funeral home ended with an exchange of letters. Stephens had worked through multiple drafts of her letter to Rost. The most pertinent news for him, as her boss, was that she would from that point forward go by a different name at work, and she would still wear professional attire appropriate for her work as a funeral director. Two weeks later, before she was leaving for her vacation, Rost handed her a separation agreement.

The last time she saw him, Stephens told me, was during the lower court case. At depositions, he said that he was uncomfortable using her name, “because he’s a man.” Instead, Rost called her “the employee.” He insinuated that the grieving families she would be guiding through the funeral process would be made uncomfortable by her. “They’re there with their family and friends in an environment that they don’t need some type of a distraction that is not appropriate for them and their family that they want to be involved in. And [her] continued employment would negate that.”

In a Washington hotel lobby a few blocks from the court this October, with members of her ACLU legal and support team dropping by briefly, I asked Stephens what the deal was with her boss. He himself said his firing her had nothing to do with past performance. “I was always, I guess, praised for my work,” Aimee said. “They were happy with it. I was able to do a lot of things other embalmers couldn’t do.” She could also draw on her background in ministry, a particular strength in comforting the grieving. “It was sudden…. At that particular point, there was no rhyme or reason as to why.”

I asked about how Rost spoke of her at depositions: Is he like that—does he have no filter?

“I think part of his problem is who’s defending him,” she replied. “I think they put a lot of ideas or things that he should be saying into his head.” His religious freedom argument, for example—he only started talking about that once ADF joined his defense team. “Even at depositions, he never looked at me,” she said. “He just sat there with his head down.” Rost would be there in court the next day.

In the weeks leading up to the oral arguments in Stephens’s case, I was sending a flurry of questions to one of her lawyers, Chase Strangio. We first met after he had helped represent Chelsea Manning when she was denied access to gender-affirming care while incarcerated at Fort Leavenworth. At the time, he hadn’t met her in person yet. I hadn’t either, but I had gone to Fort Meade to observe two days of her court-martial in 2013. I showed Strangio my notes from the day when Manning’s trial attorneys would try to explain gender identity to the military court, when the world first saw a photograph Manning had taken of herself as a woman, and when she herself got to speak. That’s the thing I was dreading about the Supreme Court, I had been telling Strangio: The justices were going to have to make a decision about millions of peoples’ lives through the lens of whatever—or whatever little—they knew about trans people, inside the narrow frame of the cases before them.

“No matter what you do in the legal system, you’re boxing yourself into the framework that exists,” Strangio told me over the phone in September. “And those frameworks are inherently conservative. Formal equality is an inherently conservative demand. It’s not redistributive. It is not about justice. It doesn’t require ‘fair’ treatment. It requires equal treatment. When you turn to the legal system, you are requiring of yourself—as an advocate, of your subjects—coherence within a conservative framework, that reifies and reinforces that framework. And in every civil rights movement, you can see this.”

In the 1940s, you could see it with Pauli Murray in her jail cell, her case not fitting well enough within the legal arguments then taking shape against segregation. But in the 1950s, Brown fit. And in the 1970s, for sex discrimination, the case that would fit was Reed v. Reed. As in Brown, it was argued before the Supreme Court by a future justice; in this case, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. As in Brown, when Ginsburg was preparing her brief, she looked to the work of Pauli Murray to draw a parallel between discrimination against black people and discrimination against women. On November 22, 1971, in a unanimous ruling, and for the first time, a state law that discriminated against women was overturned for violating the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision gave Ginsburg her first Supreme Court victory, too. She would go on to take and win many more sex discrimination cases. Reed was especially critical for putting some power behind Title VII, by articulating what sex discrimination meant under the law.

On October 8, 2019, mounting the marble steps with our chaperone to the tight press quarters, I looked right and saw Aimee Stephens, sitting in her wheelchair, waiting to go through security. I would not be able to see her in court, but there was Chase Strangio, at the table with the rest of the ACLU team, with David Cole giving the argument. Justice Ginsburg wore a red jabot with red earrings, which could not not be interpreted as a sidelong sort of commentary on the cases at hand. Then, there, direct in my sight line, was Justice Kavanaugh, his face a paler shade of red, like a summer tomato falling in on itself.

Much of the back-and-forth centered on the meaning of sex. In all three cases—Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia and Altitude Express Inc. v. Zarda, which concerned sexual orientation, and Aimee Stephens’s case, R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC—the reasoning against seeing discrimination against LGBTQ people as sex discrimination hinged on the idea that no legislator drafting the Civil Rights Act could have meant to protect people who were scarcely recognized as legal persons. Justice Ginsburg broached this in the very first question. “How do you answer the argument that back in 1964, this could not have been in Congress’s mind because in many states, male same-sex relations was a criminal offense; the American Psychiatric Association labeled homosexuality a mental illness?”

The fired employees’ lawyers’ response to this line of inquiry would become a theme. “This court has recognized again and again forms of sex discrimination that were not in Congress’s contemplation in 1964,” said Pamela Karlan, arguing for Zarda in Altitude Express. “In 1964, those were the days of Mad Men, so the idea that sexual harassment would have been reached—most courts didn’t find sexual harassment to be actionable until this court did.”

Following that important thread through the next two hours was wearying, particularly once it was subsumed under questions about bathrooms. At times, it was unclear if the justices were asking questions about sexual orientation or gender identity or both. Karlan had to counsel Justice Gorsuch once, “You’d be better advised to ask the question to someone who is representing someone who is transgender. I am representing someone who is gay.” Was this merely a confusion of categories? Or was the court expressing something that the narrowness of the cases could not address head-on—namely, that sexuality and gender are inextricable, that this was a fight over bodies and power?

Collapse the social movements of the twentieth century into this one room, and the interplay is easy to see … fears that white women voting and working outside the home would ruin their femininity … that the end of Jim Crow meant the end of white womanhood … that women’s liberation meant women would become lesbians (who both hated men and acted like them) … that the acceptance of trans men would mean lesbians would become men … and, with the bathroom litany especially, fears that trans women were really just men—and, more so, were predators. Everything being argued in the court that day was about sex, but it was also about gatekeeping and who belonged.

“May I just ask, at what point does a court continue to permit invidious discrimination against groups that, where we have a difference of opinion, we believe the language of the statute is clear?” Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Noel Francisco, solicitor general of the United States, who was defending Harris Funeral Homes on behalf of the U.S. government. “At what point does a court say, Congress spoke about this, the original Congress who wrote this statute told us what they meant? They used clear words. And regardless of what others may have thought over time, it’s very clear that what’s happening fits those words. At what point do we say we have to step in?”

Though this idea may fall outside the arguments that could be made in these three Title VII cases, it is important to recognize that two basic things animating fears over their repercussions can both be true. In the fight for LGBTQ rights, the law is too blunt and constrained, and so people do the best they can to fit within it to make a case for justice—and it couldn’t be reasonably supposed that the law as it was written in 1964 wouldn’t extend to people who today fit under that acronym umbrella, but who then hadn’t entered the common parlance. They were stigmatized then as they are today for their failure to live up to the shifting dictates of whatever “real” manhood or womanhood means in their moment. The argument against LGBTQ justice, then, is: In 1964, these identities did not exist, so these rights did not exist.

That is not to say, however, that these people didn’t exist. We know Pauli Murray existed. She led multiple lives, and left much evidence of them behind. After her law career, she had a whole other one: Like Aimee Stephens, this child out of North Carolina, who knew even then she was different but didn’t know how to live with that difference, went to seminary. Throughout the 1970s, even as Murray worked toward her eventual ordination, she corresponded with Ruth Bader Ginsburg about sex discrimination cases. In 1985, Murray died, one year after Stephens completed her ministry studies. She is not here to ask Justice Ginsburg today if she, Pauli Murray, all her selves, would be protected under the law that together they defined.

*This article has been updated to credit the work of Sam Ames, a trans civil rights attorney, in locating some of Murray’s Title VII correspondence.