I read Tom Perrotta’s Mrs. Fletcher in one day. Of course I did—the novel as irresistible trap, impossible not to devour in a sitting, is his métier. Perrotta is more entertainer than artiste, but some writers are adept at sentences and some at character and Perrotta’s genius happens to be story. It’s no wonder he’s had such a successful run in Hollywood: Election and Little Children on the big screen (the latter got him an Oscar nomination), and, for HBO, first The Leftovers and now Mrs. Fletcher.

The series adaptation of Perrotta’s 2017 book stretches over seven episodes; the network will release one weekly, clearly hoping to build a hit rather than inundate us with yet another binge. Though I’m ethically bound to honor HBO’s embargo of plot details, it would anyway be morally wrong to spoil the story that Perrotta (who wrote the first and last episodes himself) has constructed.

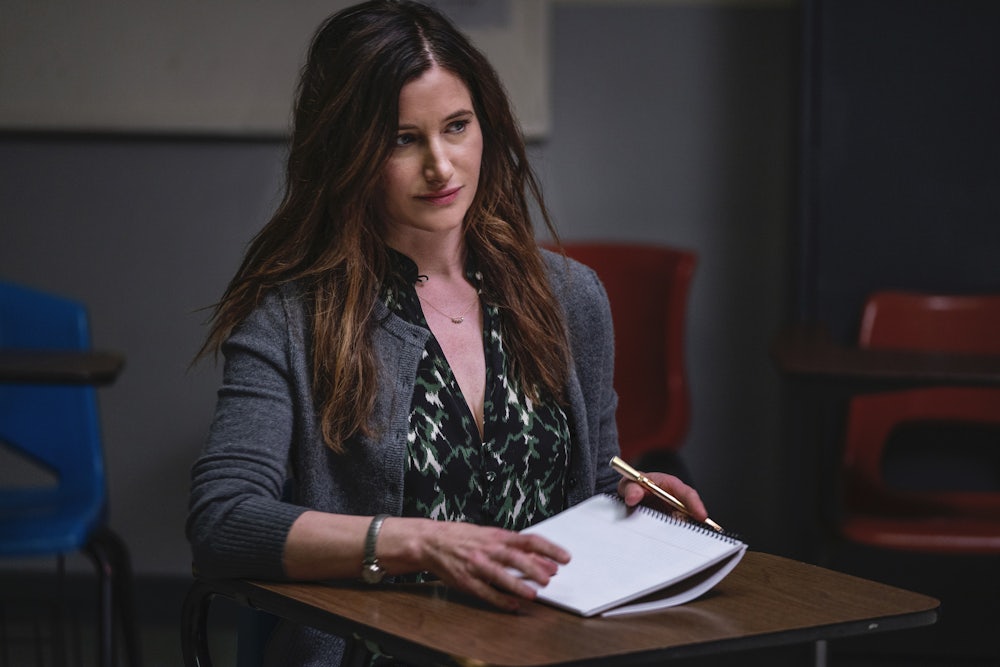

Here’s a thumbnail: Eve Fletcher (Kathryn Hahn) is a divorcee. In the first episode, directed by Nicole Holofcener, she’s helping Brendan (Jackson White), her only child, pack for college. Really, she’s doing the packing; Brendan is having one last hurrah with his high school cohort. We get a glimpse of Fletcher at work—she’s the director of a community senior center—and tangling with her ex-husband, Ted (Josh Hamilton). But mostly we see her slipping slowly toward the inexorable crisis of being an empty-nester. She’s lonely. She’s bored. She feels adrift, unaccustomed to having only her own needs to tend to. Sex isn’t the answer for her, but pornography does scratch some itch. It doesn’t seem altogether that dirty; indeed, it’s almost sweet, as though watching strangers have sex is showing Eve how to be fully human.

The first episode is a gift from Perrotta to Hahn. Not a lot happens, and Hahn makes hay of this. She goes from firm and professional after an embarrassing incident in the office to indulgent and exasperated in the scenes with her son. Hahn seems to be relishing every minute. And it’s so fun to watch her salvage the more clichéd business—the physical comedy of a petite woman loading a minivan, or the trite sight of a mom wielding a wine glass.

None of this will surprise Hahn’s fans. They’re rightly awaiting this moment: a big-budget prestige vehicle for a beloved indie-adjacent performer—the sitcom ringer (Parks and Recreation) or ensemble player (Transparent) who upstages the stars. It’s bracing to see a woman of 46 given free rein to be smart, and vulnerable, and sexy, too, and Hahn is that, at once confident and defenseless in the scenes that require her to shed both inhibition and clothing.

The storyline is informed by Eve’s increasing interest in pornography—a scold would call it addiction—and we’re obviously meant to be taken aback by this. But it’s a bit of a feint. Pornography is more narrative device or organizing principle—a shortcut to making a point about Eve’s desire to become whoever she truly is. It’s reductive to talk about Mrs. Fletcher as being about sex, which is a relief, because to aspire only to that (how dare a woman of 46 exist as a sexual being!) would be tiresome.

Based on the title, this sounds like a one-woman show. But there is a surprise in the first episode, and it’s White’s performance as Brendan. In the book, the storyline shifts between a third-person narration of Eve’s journey of self-discovery and a first-person accounting of Brendan’s adventures at college. It’s a canny choice; Brendan is so deeply self-centered that of course we only see him through his own eyes. In dramatic adaptation, absent a voice-over, the camera almost always establishes a third-person perspective—it determines how we see these characters. The challenge for White is to get us firmly inside Brendan, which is not always a pleasant place to be.

Muscle-bound and blandly handsome, White absolutely looks the part of the lacrosse-playing lummox galumphing around a college campus (one character later refers to his type as “basic white boys with pink dicks”). But the actor finds in Brendan depth and complexity. I absolutely hated him at first sight, as I was meant to, but by the season’s conclusion, I hoped for his salvation.

By the second episode, Mrs. Fletcher grows into more of an ensemble endeavor. Adaptation will always require some changes (The Leftovers departed significantly from its source material), and Perrotta is widening the scope, building a show and not a book. Katie Kershaw is superb as Amanda, one of Hahn’s employees. Zaftig, tattooed, and alluring, she’s a great foil to Hahn. Her delivery of a throwaway line (not a spoiler, just listen for the words “It’s a normal lock”) is the one moment in the whole series that made me laugh out loud. The show is interested in Brendan’s father and his new wife, in Eve’s wider circle of empty nest moms, and in the dynamics among the members of a creative writing class Eve takes at the local community college.

Mrs. Fletcher is biting off quite a bit. It veers often into trope—the post-coital devouring of a floppy slice of pizza, the slow-motion group dance montage, the introspective puffing of cigarettes, that moment of such drunkenness you cannot bring yourself to fully close the refrigerator door (I refuse to believe this ever happens in real life). I never again need to see a person dive into a swimming pool in search of epiphany. And it’s easy to spot many of the plot points coming: the guy who said he can’t make it to the party shows up at the party; Brendan’s college roommate (played by Cameron Boyce, a young actor who died earlier this year; the first episode is dedicated to him) is keeping a secret so obvious it’s a little silly.

But the show’s interrogation of pornography and pleasure and the curious, often unspoken role of sex as it relates to identity and human fulfillment is rich material. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to recount a line—“a person needs to be touched”—that feels like a statement of purpose.

Plot is Perrotta’s strong suit, and the series moves at quite a clip. The network’s striptease set-up will, I suspect, hook most viewers. Chekhov’s gun, here, isn’t a gun at all. It’s an orgasm. And it does fire—maddeningly, in the series’ very last moments. I’ll admit I want to know what comes (sorry) next.