My friend Molly had her first baby about a month ago. She watched Friends in the hospital during labor. Then she took her baby home, where she watched more Friends—the entire last five seasons, to be exact.

I was baffled. Not because I thought Friends was awful, but because I probably hadn’t given it a thought in a decade. Casting my mind back, all I could remember was an ex named Janice who screeches and a turkey jammed on somebody’s head. Surely such a program would add to the stress of childbirth, not soothe it.

But the truth about Friends is staggering. Instead of fading into irrelevance, it has only increased in popularity since it went off the air in 2004. This fall sees the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first episode’s airing, and twelve episodes of the show will be screened in theaters across America to mark the occasion. Pottery Barn has launched a tie-in range of Friends-style objets. Netflix paid WarnerMedia something close to $100 million to keep the show on its service for a single year after fans went postal over a proposed platform change in 2018. In January, the BBC reported that Friends is the most popular show among under-16s in the U.K.—currently.

This has come as a surprise. When the show became available on Netflix in January 2015, it prompted a wave of think pieces about millennials who were rejecting Friends over its outdated cultural politics. Offended by Ross’s anguish over his gay ex-wife and Chandler’s transphobic comments about his father, such essayists predicted that Friends’ supremacy would soon be over.

In a trend-bucking twist of TV fate, the opposite came true. Friends has bulldozed its way into the American canon, and is somehow more relevant than ever.

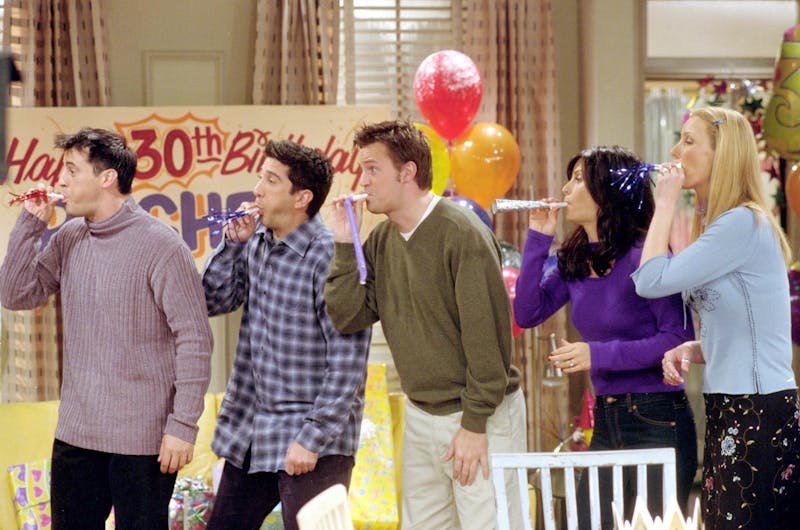

Friends ran from 1994 to 2004, and never materially changed in format during that time. A group of six young adults—Joey, Chandler, Ross, Monica, Rachel, and Phoebe—live in close proximity to one another and preserve the unity of their “family” at all costs. They reside in New York City but are rarely filmed outdoors or at work, instead mostly occupying one of two large apartments or the Central Perk café, where they regularly put their shoes on the furniture. Various romantic permutations coalesce and break apart, threatening but never destroying the family’s integrity. Outsiders (like Phoebe’s eventual third husband Mike) may only become permanent members of the community by submitting to the group’s codes; all others are shrugged off in short order.

Probably the best-known critique of Friends came from Oprah Winfrey. In 1996, she had the cast on her show, where she told them, “I’d like y’all to get a black friend. Maybe I could stop by.” Race on Friends was comparable to race on Girls: It just so happened that an entire social group was white, despite living in an extremely mixed city. Neither show intended that casting as a statement, but the effect was to alienate many people. In reality, a New Yorker would have to live a pretty cloistered life to end up in such a homogeneous clique.

And in reality, they’d have to have inherited enormous wealth to live so carelessly as the friends of Friends do. Writing for The New York Times in 2014, Ginia Bellafante tried to interpret the odd popularity of Friends among wealthy New York City teenagers. Maggie Parham, then a 15-year-old girl living on the Upper West Side, told Bellafante that she liked how the characters “all work, but they seem to be able to get out of work easily.”

Gender and sexuality were more complicated themes on the show, though no less conservative. Monica Geller speaks the first line on the first episode of Friends: “There’s nothing to tell, he’s just some guy I work with.” Beside her sits Chandler Bing, whose shod feet are resting on the Central Perk couch. “C’mon,” Chandler retorts. “You’re going out with him, there’s gotta be something wrong with him.” Next, Chandler tells the group about a dream he had in which he realized he was naked, then that his penis was a phone, which then began to ring: He picked it up and it was his mother. “Which is very, very weird,” he concludes, “Because she never calls me!” Ross enters the café, crying, because his ex-wife is a lesbian.

From its very first scene, Friends offered its viewers an odd mix of fixed gender roles and satire on them. Chandler is an indulgent portrait of self-obsessed masculinity, while Monica’s terrible taste in boyfriends recurs as a punchline about women’s inability to understand men.

Though every “friend” is straight, Friends tried to have its politics both ways by including queer characters who were simultaneously mocked and admired by the other characters. Ross’s ex Carol is certainly meant to seem smarter than him, but Ross makes many more homophobic jokes than Carol gets lines at all. (Ross reflects in the pilot that he should have known Carol was gay because she drank her beer “straight from the can.”) There is also a large quantity of trans-bashing on Friends, as Chandler bemoans his “gay dad” who seems much closer to a trans woman. In one episode, Chandler’s mom delivers this line to her ex-partner: “Don’t you have a little too much penis to be wearing a dress like that?” The laugh track goes wild.

Friends acknowledged the existence of gay people, while not treating them as quite fully human. The same was true for race: There are plenty of actors of color who played bit-parts on the show, but they never made it into the family’s magic circle.

In a doctoral dissertation titled “I’ll Be There For You” If You Are Just Like Me: An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in Friends, Lisa Marie Marshall argued, “Friends perpetuated dominant ideologies of friendship, gender, race, and class, frequently using humor to communicate these ideas.” Dominant ideology is the TV scholar Jeremy G. Butler’s term for a “system of beliefs about the world that benefits and supports a society’s ruling class,” and Marshall’s point is that, in the 1990s, the dominant ideology in the U.S. placed a premium on whiteness, heterosexuality, leisure, luxurious apartments, female beauty, and men who make jokes at other people’s expense. Friends appeared on the surface to question those ideological demands, but its heroes promoted a kind of aspirational existence that was in fact deeply conformist.

Despite its flaws, the twentieth anniversary of Friends occasioned a flurry of positive reminiscences. In The Guardian, Anne T. Donahue called it “the best ever show about 20-somethings.” In Slate, Willa Paskin wrote, “The pilot of Friends was not particularly well-reviewed, but it plays well in hindsight.” She went on: “Unlike with so much contemporary TV, there is no barrier to entry with Friends.”

But Friends is not popular because it is uncomplicated—it just seems that way because we’re so used to it. When I asked Molly why she’d chosen Friends as her TV companion of choice during the first few weeks of her child’s life, she sounded a similar note to Paskin. “At the time, I thought: This is the most basic thing I could have chosen,” she said. “But it was just so easy to watch!” It’s that very ease—the ubiquity and obviousness of the cultural juggernaut that hides in plain sight—that makes Friends difficult to wrap your arms around.

When you see the same situations acted out on television hundreds of times over the course of a quarter-decade, the fiction writes itself deep into the code of your brain. Globally, Friends is as impossible to avoid as Coca Cola. Both the story and the values of Friends have become a part of our culture the same way that Mount Rushmore came to define the American landscape: You just can’t make it go away. It’s hegemony in motion.

After long weeks of watching the show and pondering its dubious joys, only one explanation for Friends’ endurance accounts for both its cultural conservatism and its sparkling, juvenile humor.

Friends is about adults whose bonds of friendship surpass every other kind of relationship in their life, and which they prioritize over all else. Their love for one another is unconditional. Each episode introduces some kind of complication to the group dynamic, and again and again the friends resolve the conflict and return to the bliss of mutual love and support.

The only common factor in all of the statistics about Friends’ popularity is age. Young people are the lifeblood of the Friends audience. For those between the ages of 13 and 25, friendship is everything. It’s an all-consuming drama that crowds out all other concerns, including the political. Lurking beneath that obsession with friendship dynamics, however, is the subtler adolescent fear of leaving home and having to find affection on one’s own terms, out in the cold, grown-up world. Friends dramatizes a fantasy of permanent, positive love between attractive adults whose problems (financial, professional) always shake out in the wash. It’s a vision of adulthood that conforms to the emotional requirements of teenagers (not to mention the grown-ups they will become) like a tailored suit fits a gentleman.

There’s a funny moment on “The One With Rachel’s Sister,” when somebody knocks on the purple apartment door (it turns out to be Reese Witherspoon). Phoebe looks around the room and counts everybody in attendance. You see the confusion spread as the gang realize that “they”—Joey, Monica, Phoebe, Chandler, Ross, and Rachel—are all present. Who else is there?