Should nonprofit groups that buy ads supporting or attacking political candidates be required to disclose their donors? The answer would seem obvious. But in the post–Citizens United landscape—where politics are awash in funds from unknown sources, in unlimited amounts—it was entirely possible that when the Supreme Court got the chance to weigh in on that question, it might side with the defenders of dark money.

Last month, though, the court made the decision to let stand a lower-court ruling that forced dark money groups—mostly the nonprofit arms of groups such as the NRA and Planned Parenthood—to disclose the identity of donors who gave more than $200 for the purpose of influencing federal elections. Champions of campaign-finance reform hailed the decision.

“Great news!” tweeted Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island. “A blow to creepy #darkmoney forces.” Defending Democracy, an independent, nonpartisan initiative, tweeted that the ruling was a “major victory against #DarkMoney” and that it would bring more transparency to American elections, “effective immediately.” Ellen Weintraub, the Democratic vice chair of the Federal Election Commission, called the Supreme Court decision a “real victory for transparency.”

This is a real victory for transparency. As a result, the American people will be better informed about who’s paying for the ads they’re seeing this election season.

— Ellen L Weintraub (@EllenLWeintraub) September 18, 2018

/2

But the celebration proved premature. The latest FEC disclosure reports, released last week, show that most of these groups are still hiding their anonymous donors despite last month’s court order. It turns out that the new disclosure requirements are not as expansive as the reformers had hoped. There’s a gaping loophole—and Democrats are benefitting from it as much as Republicans are.

In 2012, the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), a nonprofit watchdog, filed a complaint with the FEC against Crossroads GPS, a conservative nonprofit organization co-founded by Karl Rove. CREW alleged that Crossroads, which was spending tens of millions of dollars to support Republican political candidates, was violating federal law by keeping its donors secret.

It wasn’t until three years later, in 2015, that the FEC put the issue to a vote. But the six-member commission deadlocked, as the three Republican commissioners opposed an investigation into Crossroads. Its complaint dismissed, the watchdog sued the FEC for not investigating Crossroads. The case wound its way to the U.S. District Court for D.C., which ruled in CREW’s favor this past August. When the Supreme Court refused to block the ruling, the FEC was forced to issue new guidance earlier this month.

The FEC wrote the narrowest rules possible without running afoul of the courts. The commission didn’t require all nonprofit groups that fund political ads for or against candidates to unmask their donors, as reformers had hoped it would. Instead, it only required this of groups that solicited funds specifically for that purpose. As Brendan Fischer, the federal reform program director from the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center (CLC), explained, the new requirements “won’t ensure disclosure of donors to groups that spend money on ads that don’t expressly tell viewers how to vote.”

For example, if a group raised money with an appeal to increase federal funding for birth control, but then spent the money on ads asking voters to oppose Democratic Senator Joe Manchin in the November election because he supported Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, then it wouldn’t have to disclose its donors. The group would only have to disclose them if it had explicitly solicited donations with an appeal to take down Manchin in the midterms.

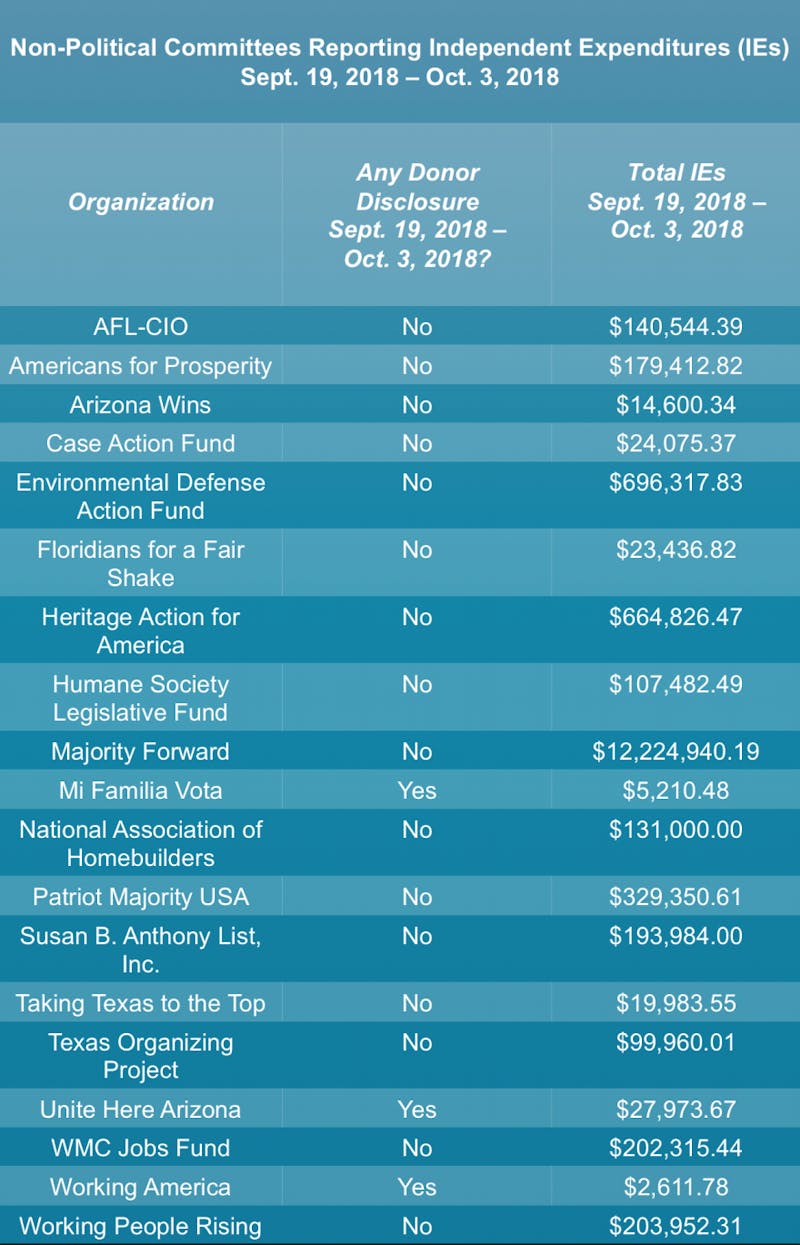

So it was no surprise when, on October 15, the FEC released the latest campaign finance filings and all but a few politically active groups continued to hide their anonymous donors. For the period from September 18 (after the court ruling) to September 30, only four of the 17 political nonprofits with independent expenditures—that is, money spent on advocating for or against candidates—disclosed their donors, according to the CLC. Only one of those groups began revealing its donors after the FEC’s new guidance, suggesting that the guidance had little impact on dark money disclosures.

Even in these few instances, the transparency only goes so far. The four groups, all left-leaning, are Unite Here Arizona, Working America, Mi Familia Vota, and Working People Rising. Their donors are largely labor unions or other nonprofits, and those groups have not disclosed their individual donors. So we still don’t know exactly where the money is coming from.

The Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity, AFL-CIO, Heritage Action and Humane Society Legislative Fund were among the dark money groups that did not disclose their donors. But the group with the most independent expenditures in the third quarter was Majority Forward, a liberal nonprofit connected to the Democratic Senate Majority PAC. The group spent $12 million on political ads between September 19 and October 3, bringing their spending total this election cycle to almost $29 million—mostly on ads against Republican Senate candidates in swing states like Florida, Indiana, and Arizona.

Majority Forward doesn’t disclose its donors thanks to the aforementioned loophole, as its statement to the FEC last week makes clear: “As a matter of policy, Majority Forward does not accept funds earmarked for independent expenditure activity or for other political purposes in support or opposition to federal candidates.”

“Democratic Party officials say they oppose dark money,” the CLC’s Fischer said, “but so far a Democratic group (Majority Forward) is the biggest spender failing to disclose its donors in the wake of this pro-disclosure decision.” (Several other dark money groups, including the right-leaning Patriot Majority and left-leaning Taking Texas to the Top, echoed Majority Forward’s reasoning for not disclosing.)

Weintraub, the FEC’s Democratic vice chair, acknowledged her disappointment: “When we first read the opinion from the court, I think we got a little over excited about what it might be able to do.” But “any additional disclosure is a good thing,” she added, and insisted that there’s “much greater cause to investigate dark money groups, independent expenditures and straw donors now than in the past because of the new disclosure requirements.”

But can her commission keep up with dark money groups? With every new ruling or regulation, it seems, these groups just find another way to remain in the dark. True transparency will require comprehensive action from Congress and the White House to change our campaign finance laws. Anything short of that is just an illusory victory.