Burkina Faso is a landlocked country, closer to the desert than the ocean. Its cities are freighted with dust, beaten into submission by the harsh sun, red, hard-packed earth, potholed, black-tarred roads, and sturdy but uninspired greenery, buildings, modern and traditional, crowding each other, all of it shrouded in a layer of fast change, the wider ambitioms of the region, and deep melancholy.

Ibrahima Sanlé Sory first began taking photographs here in the late 1950s, documenting highway wrecks near his hometown of Bobo-Dioulasso, in what was the new nation of Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso. He risked crashes every day riding around on a motorbike chasing photos. He also made a name for himself photographing the country’s emerging music scene and illustrating record sleeves.

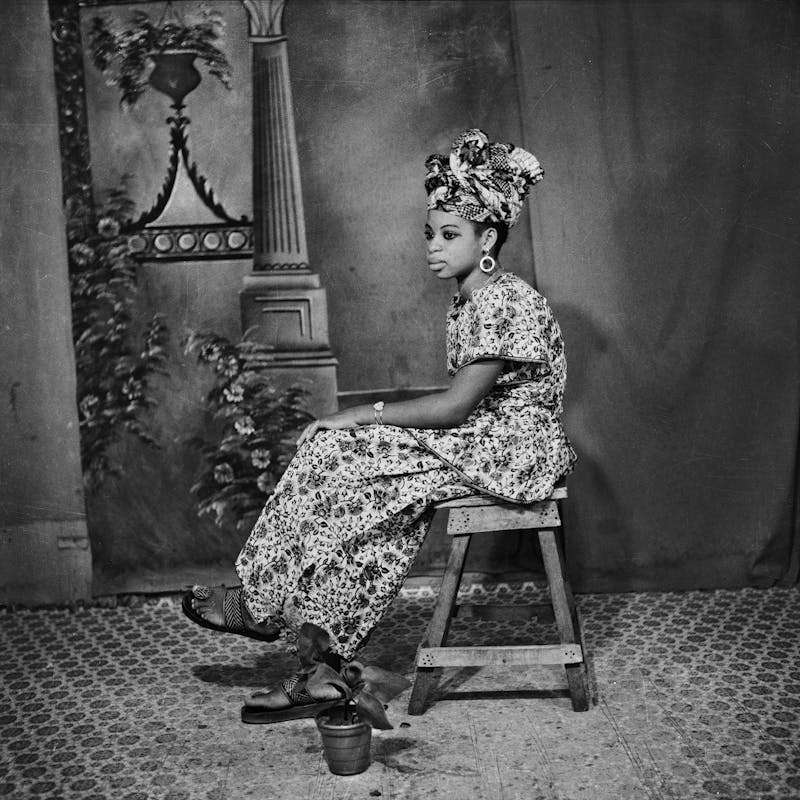

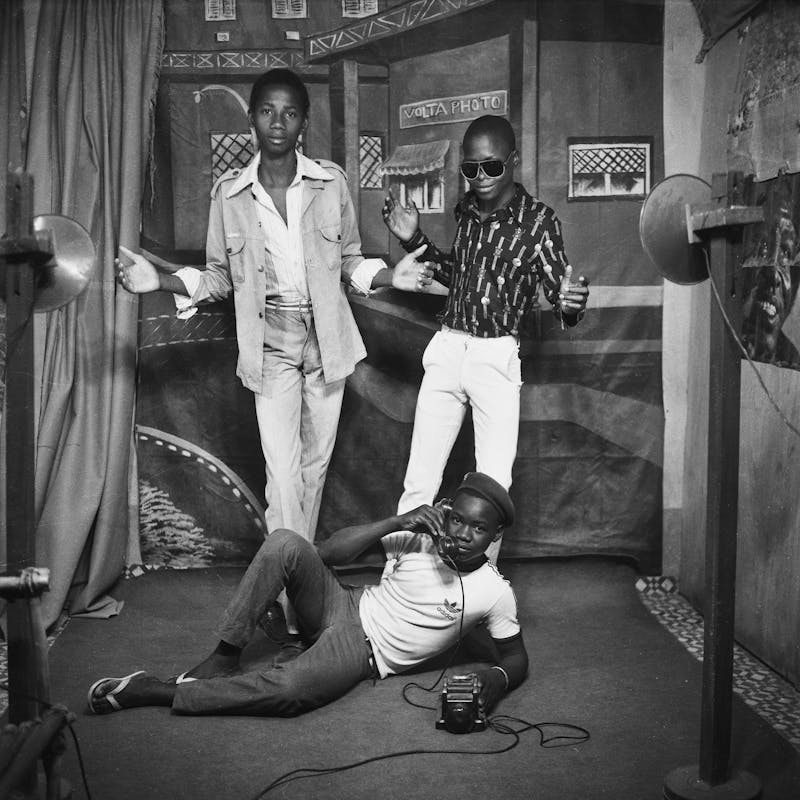

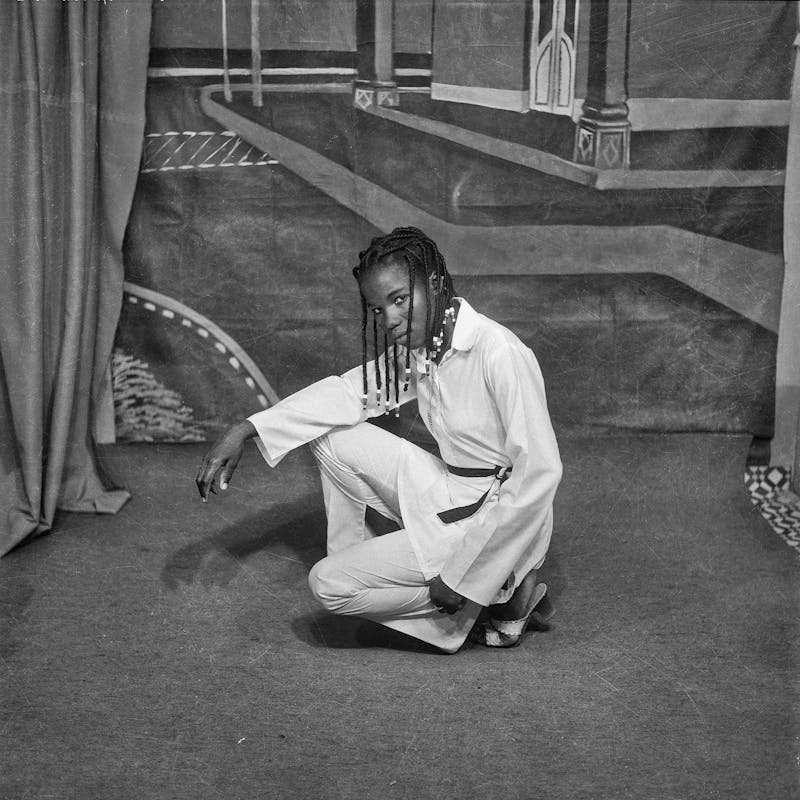

But he didn’t truly find his voice until 1960, the same year Upper Volta gained its independence from France, when he opened Volta Photo, his portrait studio. It was here that he gave shape and tangible form to the changes in his country. These photos, taken throughout the decade and into the 1980s, captured the heady and transformative mood of a young country. He was aided by distinctive costumes and backdrops, smart staging, and perspective-heavy compositions closer to Renaissance painting than photography. He portrayed his subjects with vibrancy, tongue-in-cheek wit, and deep compassion. They leave one breathless. They are like liner notes of a new culture.

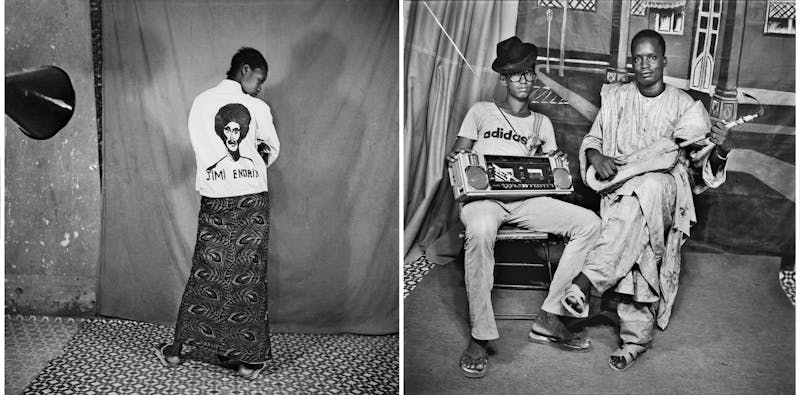

The backdrops, some of which Sory commissioned from artists in Ghana, Benin, and Ivory Coast, seethe with the energy of escapism, brim with fantasy—a man, Air Afrique suitcase in hand, stands in front of an airplane with its door open, boarding-stairs leading to the freedom of an imagined city, an imagined life. (Sory says this backdrop was particularly popular with people who hadn’t traveled.) The props range from medieval armor to modern-day boom boxes, muscular embodiments singing with the global promise that black culture in this part of Africa held in the 1970’s.

A self-portrait from the era shows Sory, shirtless, holding his Rolleiflex twin-lens, medium-format camera at stomach level, smiling. What the image doesn’t reveal is the tribal marks cut into the sides of his face that wrinkle when he laughs, like the whiskers of a mischievous cat. Likewise, the ordinary people captured in his photos—musicians, dancers, couples from the city’s nightlife—are transformed, made beautiful through the intimacy of his lens. Perhaps they created new selves for him, his camera driven by Bobo Yéyé music, the postcolonial soundtrack of Burkina Faso, and the hopes of a generation.

The ensuing years have complicated those hopes: coups, government collapse and rebirth, and more recently, the advent of Islamist terrorism—fighters pushing against the remaining vestiges of Western colonialism. Photography can make artifacts and memories, create lasting symbols of a moment. Sory’s work, seen today, seems to beckon across the gulf of time to a past all but lost, a past mired in legends of emirs and mansas and griots, a past that reforms into an ever-evolving and frenetic present.

This man, identified by Sory as the “Commandant,” seems giddy with excitement about traveling abroad.

Sory’s background illustrating record sleeves is evident in many of his photos, as is the intersection of Western and African musical cultures, with influences from hip-hop and Jimi Hendrix and the sounds of Burkina Faso’s djeli, or traveling musicians.

Sory’s portraits of ordinary Burkinabes conveyed both the exuberant energy of a newly liberated country and the beauty and dignity of its traditional culture.

Sory used props and occasionally even provided clothes for his portrait subjects, allowing people to role-play and create personas that evoke the period’s optimistic spirit.

Sory often kept his gallery, Volta Photo, open late into the night. He would sometimes have two assistants working while he was out snapping photographs at nearby parties or dances. Local residents also liked to stop by the studio, listen to music, and have their portraits taken.