Great memoirists are contortionists. They look at their own lives from above, below, ahead, and behind—bending their limbs and twisting their torsos into the kind of knots that shouldn’t be possible for humans. “I had placed myself behind my own back,” Augustine wrote of the years before he converted to Christianity, “refusing to see myself.”

The Confessions remains one of the canon’s most extraordinary acts of contortion, because Augustine found a way past that refusal, coming to see himself in full. He told the story of losing his faith and then finding it, but the Christian-turned-Manichean-turned-Christian-again is a patron saint for memoirists of all kinds: the faithful and the faithless, the somes and the nones, the forevers and the never-evers. Two of his most recent acolytes are the poet Patricia Lockwood and the editor Macy Halford, both authors of new memoirs about their spiritual lives.

Lockwood’s twisting and turning starts with her title. Priestdaddy isn’t just a play on the various honorifics for clergy in the Catholic Church, it’s the peculiar status of Lockwood’s father: Originally ordained in the Lutheran Church, he converted to Catholicism and received a dispensation from Rome to bring along his wife and children. Priestdaddy is about what life is like for any pastor’s kid, but this one has a genuine gift for words. Lockwood reads “string quartet” and makes a cat’s cradle, “penniless” and thinks of copper, “aristocrat” and sees a cravat. Imagine Flannery O’Connor on a standup comedy tour, or John Berryman if his sonnets had been “The Dream Psalms.”

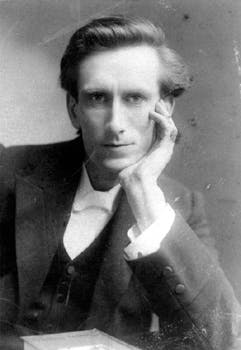

Priestdaddy is less furtive and more fun than Macy Halford’s My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir, which is a studied look at religious history. Halford was raised a Southern Baptist by her mother and grandmother in Dallas, though like Lockwood she tells the story of her faith partly through the biography of a preacher: not her own father, but Oswald Chambers, author of the daily devotional that Halford has read since she was a teenager. My Utmost for His Highest has sold tens of millions of copies since it was first published in 1935, and Halford’s memoir grew from her surprise that millions of other, more conservative evangelicals, including another Texan, President George W. Bush, have found the devotional meaningful to their lives.

Like any two stories of belief, My Utmost and Priestdaddy have next to nothing yet nearly everything in common. Both Halford and Lockwood try to interrogate their spiritual ancestors, taking religious faith as a frame for broader ideas about what we inherit from our families and from the cultures around us, including literary ones. In an increasingly secular age, it is rare to see two writers turn themselves into pretzels as they try to understand belief from so many more angles than their own.

Patricia Lockwood’s father, previously an atheist, converted to Christianity after watching The Exorcist more than 70 times while aboard a naval submarine. He calls it “the deepest conversion on record,” and Lockwood asks readers to imagine what it must have been like for him: “You’re a drop of blood at the center of the ocean, which plays a tense soundtrack all night long, interspersed with bright blips of radar. Russians are trying to blow up capitalism and you’re surrounded by dolphins who know how to spy…you look up at a screen and see a possessed twelve-year-old with violent bedhead vomiting green chunks and backwards Latin.”

When Greg Lockwood returned from sea, he went to college and then seminary, and finally became a pastor. He moved his family around the Midwest from parish to parish, first in the Lutheran Church, and then in the Catholic Church, sometimes replacing priests removed during the early days of the sexual abuse scandal. “I don’t think that was the first time he was ever sent somewhere to restore a congregation’s faith,” Lockwood writes of one such placement, “People place more trust in him—he’s married, he has children. He wouldn’t want you to draw a lesson from that, but I don’t see how you could help it.”

Here and throughout the memoir, there is a jellyfish quality to Lockwood’s narration. It is easy to be distracted and delighted by her strange, phosphorescent prose, but the wisp of an idea brushes against you, and before you know it, there’s a welt. What seem like drifting plot points in her family’s story linger and sting, as when she suggests that the requirement for priests to be celibate may have had something to do with the widespread sexual abuse in the Church. Elsewhere, she observes that anti-abortion activism can distract from deeper commitments to life (“She stayed with us and got big as houses,” Lockwood says of a woman named Barbie, “then she had her baby, and we never really heard from her again.”) and that caregivers who rarely falter professionally can profoundly fail their own families. (After Lockwood attempts suicide by taking one hundred Tylenol, her father, the beloved priest, says coldly, “I just want to thank you for ruining our anniversary.”)

One of five children, Lockwood is the only one to have inspired a sermon titled, “The Prodigal Daughter.” By age six, she knew that she wanted to be a poet, and she began studying the floors of her father’s churches instead of their altars. She substituted her family’s worship of the Word for a new faith in words, but found out for herself that no faith can be static. “To prize traditionalism above all else in a church that began in revolution is to do a great violence to it,” she says of Catholicism in the memoir, and then confesses: “I feel the same ache for the past in myself: to uphold the columns of literature, of grammar, of the Western tradition. The English language began as an upheaval; I am not protecting it when I try to guard it against change.”

Her new Jesus Christ, she says, is Geoffrey Chaucer, and he “walked across the water telling dirty jokes, made twenty stories stretch to feed a million people, spelled the word ‘cunt’ five ways, performed miracles.” Those are the words of a convert with a boundless tendency to break taboos, so much so that her poetry can sometimes seem a little scattershot. When her mother asks how she writes her poems, Lockwood says “start by thinking sideways,” and then “look at the wall but really look through it.” It’s satisfying to hear her mother’s response (“Sounds like a recipe for insanity”), and even more satisfying to watch as the sense-making requirements of prose shape Lockwood’s voice into something more sane but every bit as strange as what she’s done with verse.

Lockwood’s religious iconoclasm was born and bred in the Midwest, but her literary rebellion took shape later in life, as she and her husband—a newspaper editor she met online in a poetry chatroom—moved around the country for his work. They settled variously in Hebron, Kentucky, near the home of the Creation Museum; Keene, New Hampshire; Colorado Springs; Stuart, Florida, where she worked at a Key West-themed diner; and then Georgia, where he sneaked puns into the headlines of The Savannah Morning News. In the first dozen years of their marriage, Jason was the Leonard to her Virginia, she says; while he held down a steady editing job, she mostly read and tried to write poetry. One by one her submissions found a home, in journals like Poetry and in magazines like The New Yorker. But then suddenly Jason’s glasses no longer let him see, and the couple learned that he had advanced cataracts.

His first surgery didn’t work. His second surgery didn’t work. A few surgeries later, and Jason still couldn’t read a page, much less edit a newspaper. He quit his job, and without any income, the couple had to leave their Monk’s House in Georgia, taking an upstairs bedroom in the rectory of her father’s parish in Kansas City. That’s when Lockwood started writing Priestdaddy, doing the same contortions Augustine had done all those centuries before, only in reverse, telling the story of how she left the church. She resurrects the child who ate unconsecrated communion wafers like potato chips, loved going to youth group in a basement that was “40 percent shag carpet and 60 percent Bible verses,” and believed in a God whose love, mercy, and judgment could be found “on this earth in an unusually patriarchal form.”

Like “Rape Joke,” the poem that made her famous, Lockwood’s memoir is irreverently reverent. She looks back with longing at the faith she left as soon as she could, and the family she never will, telling the kind of stories that humiliate and humanize both. Priestdaddy proves over and over that Christianity isn’t as dull as you’ve been led to believe, and that religion isn’t our age’s only absurdity. By the end, her father’s devotion to heaven doesn’t seem any stranger than her own obsessions with stanzas and tweets; her mother’s sacrifices for her father’s vocation don’t seem any less admirable than her own husband’s life as an amanuensis.

If Patricia Lockwood is a prodigal daughter, then Macy Halford is an obedient sibling. Halford tries to rescue the archaisms that Lockwood rejects, including the very form from which she has drawn her inspiration. A devotional is a curious thing: Somewhere between an almanac and an astrology column, it’s both a systematic way of reading through the scriptures and a somewhat superstitious way of trying to align your days with the will of God. Typically, a brief selection from scripture prefaces a longer passage of contemporary reflection. Denominational presses publish monthly and seasonal devotionals that churches distribute, and commercial presses sometimes market annual devotionals, including one a few years ago called The President’s Devotional: The Daily Readings That Inspired President Obama.

As recently as a few decades ago, such an explanation would have been entirely unnecessary in these pages or any others. While Christianity remains prominent in public life, it has become so marginal in many private lives that the idea of a devotional might be unfamiliar even to those who identify culturally with the Christian faith. That the most popular faith in America is so precariously positioned—structurally omnipresent, but substantially obscure—is what makes a book like Macy Halford’s so fascinating. Oswald Chambers’s My Utmost for His Highest remains one of the most popular devotionals of all time, and yet the daily spiritual guide of millions of Christians is utterly unknown to almost everyone else.

Halford’s book is best when it explains how Chambers’s book became a bestseller. Born in 1874 in Aberdeen, Chambers had wanted to become an artist, but failing at that, he followed his father into the ministry. While serving as chaplain during the First World War, he died after an emergency appendectomy. What the world knows of him is thanks to his wife, a woman named Gertrude Hobbs, who trained as a stenographer, and whose own identity was to be shorthanded, and shortchanged, for all of history: called by her husband his “Beloved Disciple,” she became “B.D.,” and then “Biddy.” As Hobbs followed her husband around the world, she filled notebook after notebook with his lectures and sermons. When he died, she continued his work among the British troops in Egypt, and when she returned to England, she prepared a full manuscript from excerpts of his work that became My Utmost for His Highest.

It’s a beautiful devotional, with lovely, lyrical entries about journeys and walks, barriers and missions. “Have You Ever Been Alone With God,” it asks in January, and then “Will You Examine Yourself” in July. In late August, on a day devoted to “Living Your Theology,” it cautions: “Beware of not acting upon what you see in your moments on the mountaintop with God. If you do not obey the light, it will turn into darkness.” A month before, in a more meteorological meditation, it notices: “In the Bible, clouds are always associated with God. Clouds are the sorrows, sufferings, or providential circumstances, within or without our personal lives, which actually seem to contradict the sovereignty of God. Yet it is through these very clouds that the Spirit of God is teaching us how to walk by faith.” There are entries about heaven in March, May, June, July, October, November, and December, and about hell in most of the rest. There is a lot of talk about crisis and common sense; sins are frequent, but not too serious, with envy in two entries and lust in nine.

Although there were many other devotionals in the centuries before, and many others in the century since, the Fellowship Foundation promoted My Utmost for His Highest in the United States, and it was read aloud by Bill Wilson and Bob Smith at early meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous. Together, those institutions created an audience for the work Biddy Chambers had crafted, and eventually the book became a cornerstone of Billy Graham’s ministry. That is how it came into the life of Wally Amos Criswell, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, one of the largest congregations of Southern Baptists in the country and the home church of Macy Halford.

Halford muddies her chronology in the memoir, but the tick-tock of Oswald Chambers in her life would read something like this: she first met him at thirteen in Texas when her grandmother gave her a copy of My Utmost for His Highest to celebrate her baptism, and she started reading him regularly a few years after that, at Barnard College and then at Cambridge University. He stayed with her in New York while she worked as an editor at The New Yorker, and followed her to Paris after she’d quit her job in order to write full-time. “How many books,” she asks, “had the power to evolve with a reader over the course of a lifetime, never growing tiresome?”

Chambers died exactly one century ago, and Halford has been reading him almost daily for more than fifteen years. It’s a remarkable relationship, longer than many marriages. And yet instead of a spouse, by the end of the memoir Chambers still feels like something of a stranger. Too often just when you wish she’d tell us more about him or the faith his work has nurtured in her, she turns away, telling us instead about a book party in Manhattan or midnight philosophizing on Parisian roofs. Halford wants to defend Chambers, but she ends up devoting much of her memoir to distancing herself from his other admirers, evangelicals whose politics she doesn’t share. Her religious belief, though it persists even in the literary capitals of the world, is far less public than personal and more pietistic than political.

Both Halford and Lockwood distance themselves from the more controversial aspects of their respective traditions, performing a familiar contortion of contemporary religious memoir: Priestdaddy accomplishes it right away with its heretical title, forgoing a subtle nod for an audible headshake, indicating that while the author was once Catholic, she definitely isn’t any more. My Utmost waits only a little longer before assuring readers that while the memoir may be the work of a believer, she’s not that kind of believer. Halford’s apologia is as gentle as Lockwood’s renunciation, and despite very different experiences, they arrive at the same secular-sounding meaning: “we all must learn to live with mystery,” says Halford; “faith and my father taught me the same lesson: to live in the mystery, even to love it,” says Lockwood.

Appeals to mystery are ancient for a reason, and there is nothing wrong with echoing the ancients. But there is something surprising about how two writers with such different religious origins and conclusions arrive at the same evocative vagary. Instead of surrendering as so many spiritual memoirists have in the past to what cannot be known about the divine, both find themselves moved by the infinite mystery of other people: families of origin as well as those fellow travelers whose politics we might abhor but whose religious practices we share. These writers aren’t just craning their necks to get a better look at their own souls; they’re looking around at how, in our theologically strange days, other souls are formed and find their way.