John Le Carré’s

pen name is perhaps the greatest and most enduring of his inventions. Born

David Cornwell, he wrote his first three novels while serving as an MI6

Intelligence Officer, leaving only when The

Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) brought him sustaining success. The

alias was a proviso of his spymasters, who were happy for him to fictionalize

the secret world rather than expose it in more literal ways. “How much our poor

beleaguered spies,” he writes in his new memoir, The Pigeon Tunnel, “must be wishing that Edward Snowden had done

the novel instead.”

Le Carré’s world of spies and Snowden’s are of course very different. Gone is the neat division between the Soviet and American empires, as well as the immediate threat of nuclear apocalypse. The clash between capitalist and communist master narratives of history has been supplanted by the reigning orthodoxies of neoliberalism. The human element of espionage and conflict has been reduced by cyber and economic warfare. Cold War spying was often done over drinks within London’s clubland, whereas British and US security services now operate under legislative oversight. And it was highborn intellectuals, like the Cambridge Five, who betrayed secrets out of allegiance to the “other side”; whistle blowers like Snowden and Chelsea Manning are democrats concerned by clandestine overreach.

Le Carré made his name as the unparalleled chronicler of the older world. But when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, so too did the geopolitical backdrop of his narratives. As his biographer Adam Sisman notes, “David was a victim of his own success. To most people, the name John Le Carré was synonymous with the Cold War; more than any other writer of his generation, he had shaped the public perception of the struggle between East and West”. When that struggle was over, Le Carré’s friends would ask, “Whatever are you going to write now?”

The avatar of today’s intelligence community is Snowden, not Smiley. And since 1993, when Le Carré published The Night Manager, he has made conscious efforts to move with the times. The targets of his invective remain the powerful and the corrupt. Yet the setting is no longer the confrontation between the pax americana and pax sovietica, but the lawless interplay between the state and corporate power. The Night Manager’s villain, Richard Roper, is an English businessman and arms dealer, secretly propped up by “espiocrats”—officials high up in the British and U.S. security services. The Constant Gardener (2001) takes on a pharmaceutical conglomerate that experiments on African tribal women in clinical trials. Our Kind of Traitor (2010) deals with the collusion between Russian money launderers, British bankers, and politicians. And his most recent novel, A Delicate Truth (2013), turns on the outsourcing of war to private defense contractors. “War’s gone corporate, in case you haven’t noticed,” declares one British minister.

David Cornwell, then, has had to invent two Le Carrés: If the second incarnation—the Le Carré that looks beyond Cold War and toward new world disorders—seems more relevant, it is the first—the post-imperial Le Carré—that we keep coming back to. In The Pigeon Tunnel, Le Carré tries to provide some kind of genesis story about his own relationship to the secret world, as well as those of his fictional characters. The result is not a memoir, but a disconnected set of anecdotes that, on the surface of things, do not seem to tell us more than we already know.

Both Adam Sisman’s biography and The Pigeon Tunnel tell the same story about Le Carré’s genius for inventing characters, particularly the wary outsider characters that populated the postwar secret services. It was an art Le Carré honed since childhood. People who had miserable upbringings, he says, are “pretty good at inventing themselves.” His father, Ronnie Cornwall, was a conman, jailbird, and sexual tyrant, while his mother, Olive, snuck out on the family when he was five. Tactics of evasion and deception were the “necessary weapons” of his youth, as was the need to adopt the manners and lifestyles of his peers, “even to the extent of pretending…. All this no doubt made me an ideal recruit to the secret flag”.

Many of Le Carré’s most fleshed out characters in the early novels—Magnus Pym, the motherless spook with a corrupt father; or Jumbo Roach, the unhappy schoolboy and “natural watcher” in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy—had the same backstories as their creator. There was also psychological heft to the torment of Pym in A Perfect Spy (1986), who is torn between personal and institutional loyalties. On every page of Tinker, Tailor, a story about a Soviet double agent inside MI6, you tasted the acrid stench of paranoia and cigarette smoke that consumes its cast of disenchanted romantics. Readers might have doubted the sincerity of these characters—after all, they deal in subterfuge, role-play, and betrayal—but never their credibility.

Europe was reduced to ashen scenes of deserted backstreets and dingy offices, rusted cars and ill-fitting clothes, rasping cupboards of dossiers fastened with pins and paper clips. Le Carré deliberately avoided making his characters heroic. He even conceived a new and eccentric vernacular for his spies, who spoke of “lamplighters,” “scalphunters,” “reptile funds,” and “moles” (some of these terms have subsequently been adopted by actual spooks). Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, describes his fellow agents as “just a bunch of squalid, seedy bastards like me: little men, drunkards, queers, hen-pecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians.”

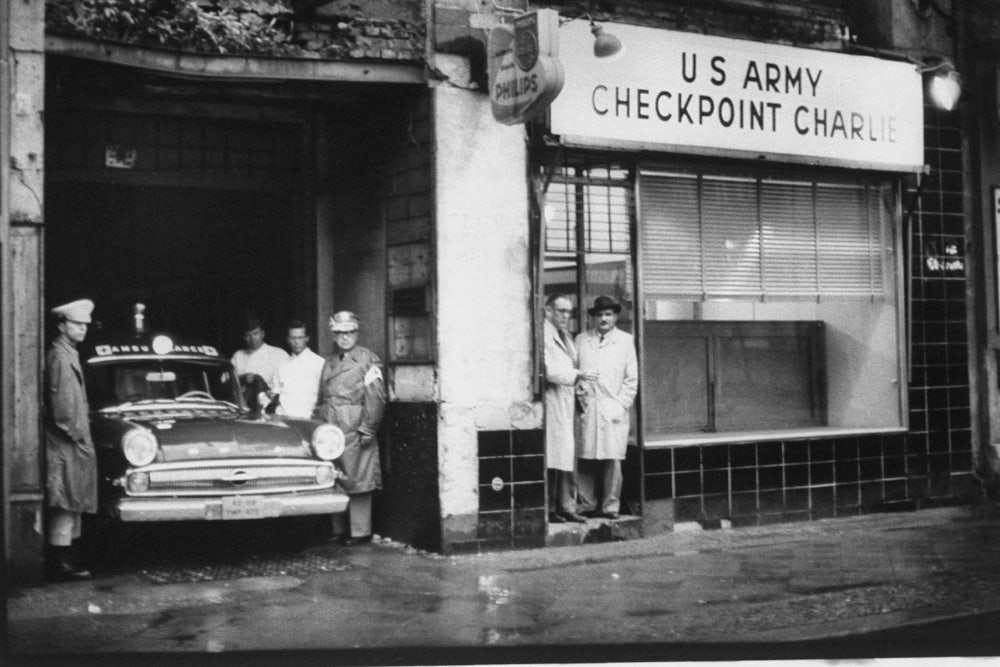

Another unique quality of Le Carré’s work was the way it broke from official western and Soviet propaganda. The duality between good and evil, espoused by both sides, was rejected for a world in which the Berlin Wall was not a border separating democracy from dictatorship, but the vanishing point of their shared practices and corruptions. The resemblances were personified in the rivalry between George Smiley and his tenebrous archenemy in Moscow, Karla. Smiley is, for the most part, cast as the nobler spirit of the two. But in the end brings his rival down by using Karla’s estranged and mentally ill daughter as a bargaining chip. When Karla defects to the west, Smiley feels ashamed rather than triumphant. ‘“George, you won,” said Guillam as they walked slowly towards the car. “Did I?” said Smiley. “Yes. Yes, well I suppose I did”’.

Le Carré had great success dramatizing the hidden realms of cold war espionage. But he was pigeonholed as genre writer. “I was chronicling my time, from a position of knowledge and sympathy,” he told an interviewer. “I lived the passion of my time. And if people tell me that I am a genre writer, I can only reply that spying was the genre of the Cold War.” Le Carré perfected that genre—even if his portrait of that time displeased many of his ex-Cold War warriors; in the opening chapter of The Pigeon Tunnel he describes being almost assaulted at a drinks reception by an MI6 officer who accused him of “making clowns of men and women who love their country and can’t answer back.”

In The Pigeon Tunnel, Le Carré writes of how he became concerned with “the fate of subject nations” after 1989. He had always possessed a strong contempt for American foreign policy and Britain’s fatal reverence for Washington. Already in A Perfect Spy, as well as Tinker, Tailor, and The Honourable Schoolboy, it was the imperious designs of the United States, as opposed to Soviet communism, that was the underlying threat. Like Graham Greene a generation before, Le Carré saw American interventions as the source of so many disasters, and this became more explicit in his novels.

In the foreword to a new edition of The Tailor of Panama, published in 2001, Le Carré denounced “the long, dishonorable history of United States colonialism in the region.” America was not fit to run the post-Cold War order, and “the sooner Britain and Europe wake up to that fact, the better”. This attitude intensified in the wake of the invasion of Iraq. On its publication in 2003, reviewers converged with skepticism on Le Carré’s smoldering fury in Absolute Friends, a story about U.S. neo-imperialism that Lev Grossman called “a work of fist-shaking, Orwellian outrage.” In A Most Wanted Man (2008), Le Carré confronted the war on terror and the ruthlessness with which governments pursue it.

Englishmen of Le Carré’s generation possessed a latent anti-Americanism. It was partly a legacy of American involvement in the Second World War, and the occupation-like presence of Britain by all those GIs who were, as the expression went, “over paid, over sexed, and over here”. But it’s clear that with age Le Carré became much angrier at the world’s injustices. In 2005 he suggested that Britain was heading for fascism: “Mussolini’s definition of fascism was that when you can’t distinguish corporate power from governmental power.” His recent novels can be read as studies in concentrated disgust. A post-Blair fury bursts from the pages of A Delicate Truth, for example, as Le Carré thunders against the success of characters like Jay Crispin, who have a “sheer, wanton, bloody indifference to anybody’s interest but their own.”

Although Le Carré has been applauded for bringing his anger to bear on some of the world’s most deplorable incidents, such indignation has come at a cost. There is something disappointingly cinematic about Le Carré’s new fictive realms. Whereas his early books were defined by their intriguing moral gray areas, Le Carré’s recent endeavors are unequivocal in depicting good and evil. All suspense is lost when the culprits—Big Pharma, arms dealers, or Russian mobsters—are recognizable from the very beginning. The old characters were darkened by inner torments, whereas now their thoughts and motivations are crystalline. In the end, Le Carré’s novels have become less concerned with the assertion of truth, and the means of attaining it, than with who wins and who doesn’t. They are, as David Remnick described The Night Manager, “Goldfinger for grown-ups.”

Much of the autobiographical ground Le Carré covers in The Pigeon Tunnel has already been reported in Sisman’s biography, and very little of it shows connections between his late novels and his most formative experiences. He recounts meeting a Russian gangster in a Moscow nightclub, which concludes with him being told, via his translator, to “fuck off.” There’s a nice account of lunching with Joseph Brodsky when the exile-poet learns of his Nobel Prize. And it’s hard not to be charmed by the tale of his dancing with the PLO leader, Yasser Arafat at a Palestinian school for orphans on New Year’s Eve.

The author’s globetrotting testifies to more than an irresistible wanderlust: his frequent encounters with the illustrious and powerful also indicate his own status as a world-famous writer; his deep concern for forgotten places like Ingushetia, and their struggles for freedom, independence, and prosperity; and most of all his abiding fascination with the invention of character. People who reinvent themselves for survival, such as those former KGB officers who became gangsters and businessmen after 1990, fascinate him. He is obsessed with how the public performances of warlord and world leaders, revolutionaries and poets, contrasts with their private personas. “Men and women of power drew me because they were there,” he writes, “and because I wanted to know what made them tick”. The Pigeon Tunnel is a lesson in observation, and the recreation of character.

But there’s little in The Pigeon Tunnel to remind us why we should be interested in what Le Carré has to say. With its disconnected set of anecdotes, lack of synthesis, and staccato rhythm, the whole thing feels like a rushed job rather than a sustained meditation with the kind of intricate narrative arc for which its author is so well known. The more recent novels might make him relevant in subject matter, but there’s much less psychological insight into the inner sufferings of their protagonists. The glamorous locations and refined personalities feel far removed from the leaden world of economic austerity and the west’s deathbed paranoia. And on thrills alone, his newer books are less gripping than, say, No Place to Hide, Glenn Greenwald’s real-life account of Edward Snowden’s revelations about surveillance.

Le Carré’s continued significance is still to be found in the Cold War novels. For American and British readers, classics like A Perfect Spy, Tinker, Tailor, or Smiley’s People have acquired a renewed urgency. Le Carré gives us a chance to reflect on what Snowden’s revelations tell us about the state of our societies. Le Carré still believes that an intelligence services are “not an unreasonable place to look” to explore a nation’s psyche. Secret services are a true measure of a nation’s political health, “the only real expression of its subconscious.” What Snowden revealed was the awesome paranoia and state-corporate collusion that are the hallmarks of Le Carré’s entire oeuvre. And Blake Morrison described him as “the laureate of Britain’s post-imperial sleepwalk.” Following the UK’s exit from the European Union, Brits might turn to him for clues as to what life might look and feel like as the country takes several more steps toward jaded irrelevance.

These novels are a study in loss. Characters like Percy Alleline, Bill Haydon, Roy Bland, and Toby Esterhase—Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, and Beggerman—are world-weary officeholders who were once trained to empire. But now it is “All gone. All taken away.” Just as his protagonists meet symbolically-charged endings— Alec Leamas dies on the Berlin Wall, George Smiley ends compromised and ashamed, Jerry Westerby is killed in Hong Kong, and Magnus Pym commits suicide—Le Carré’s novels remind us that the future is likely to be one darkened by a “Gothic gloom.”