In February 1988, Fred Barnes, then the White House correspondent for The New Republic, marveled at the refurbished George H. W. Bush who had appeared on stage in the first five Republican debates that winter and spring. “Who’d have guessed that Bush would perform so memorably in the debates?” he wrote. “Who’d have suspected that Bush would be funny, assertive, confrontational, succinct, and very, very quotable?”

Barnes wasn’t the only one surprised. In October 1987, Newsweek had run a cover story called “Bush Battles the Wimp Factor,” and the epithet stuck. Bush was indeed awkward in person—wooden and deferential—and his campaign was struggling out of the gate. He finished third in February’s Iowa caucuses, and the Connecticut WASP was still struggling to shake off the impression that he was an elitist blueblood, out of touch with the American heartland. In almost every debate, though, he was a different candidate entirely: deft and aggressive, even charming at times.

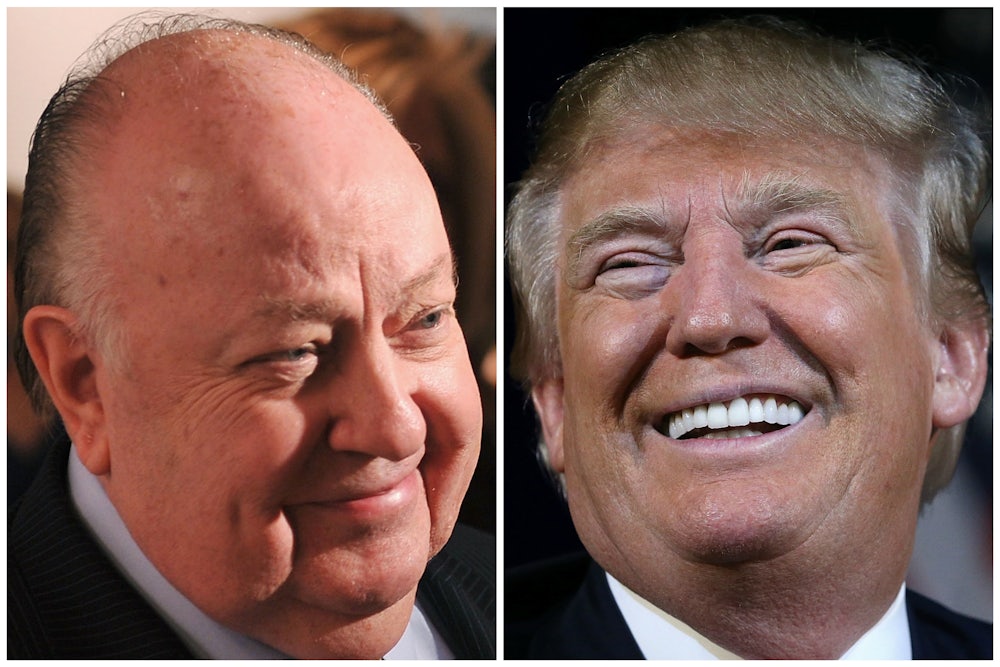

Bush owed his transformation to one man: Roger Ailes, the political wunderkind Time once called the “Ernest Hemingway of consultants.” Long before he was a chief misogynist at Fox News—the network he founded and transformed into the conservative cash cow that now rakes in over $1 billion in profits a year—Ailes was one of the most sought after political operatives in Washington, known for his hardball tactics and instinctive flair for political theater. He would spend the 1988 cycle remaking Bush—picking out flattering shirts for him, drilling him in debate prep, even, Time reported, plucking scraggly hairs from his eyebrows before important interviews.

Now, Ailes is returning to his roots. In August—shortly after New York magazine exposed his serial workplace harassment, bringing his reign at Fox to an end—he was rumored to be helping his “longtime friend” Donald Trump prep for the presidential debates. His involvement is key to understanding whether Trump can beat expectations in his first debate against Hillary Clinton on Monday—and exactly how he can do it.

Ailes entered politics in 1967, after running into Richard Nixon backstage at the Mike Douglas Show. Their first meeting is often recounted in profiles of Ailes: When the former vice president complained that TV was a gimmick, Ailes replied, “Television is not a gimmick, and if you think it is, you’ll lose again.” He joined the effort to make Nixon “new” the following year, staging fake town hall events where the candidate answered preselected, softball questions from a cheering audience of handpicked conservatives. “An applause machine,” Ailes called them fondly.

He later became known for going for the jugular. In 1984, he won Mitch McConnell his Senate seat in Kentucky, crafting vicious attack ads that featured bloodhounds chasing incumbent Democrat Dee Huddleston for the same thing Fox News has hounded Clinton for over the past year: giving speeches for money.

But it was his uncanny knack for transforming candidates into zinger-spouting killers in debate prep that sealed his reputation as one of the best political impresarios in the business. He famously rescued Ronald Reagan after a disastrous first debate performance in 1984, drilling him until he could recite what would become perhaps the most iconic line in presidential debate history. Barnes wrote:

Reagan had bombed in the first encounter, reviving concern about his age and mental agility. In practice sessions, Ailes says, Reagan’s advisers were too critical of him, destroying his confidence. At one point, Reagan gave a good answer in practice, but no one congratulated him. Ailes shouted from the back of the auditorium in the Executive Office Building, “Mr. President, that was a terrific answer.” Reagan smiled.

Ailes is wrongly credited with feeding Reagan his best line, but Ailes’s role was pivotal nonetheless. After the last major practice session, Ailes asked, “Mr. President, what are you going to do when they say you’re too old for the job?” Reagan was silent for a bit, then said he remembered an old line. Ailes practiced it with him, and in the debate Reagan fired it off, without pause: “I am not going to exploit for political purposes my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” Even [Walter] Mondale was forced to crack a smile.

Barnes—now a Fox contributor and executive editor of the Weekly Standard—had long believed that political consulting was bogus (he wrote a 1986 piece in the New Republic called “The Myth of Political Consultants”). But after watching Ailes work his magic on Bush in 1988, he seemed to change his mind, writing, “The effect of Ailes on Bush is unmistakable…. The Ailes theory is that you can win with a sharp line or two, since that’s what most of the electorate will see on news shows. Ailes coaches his candidates to do well in the sound bites, and Bush has scored heavily.”

Ailes was also responsible for encouraging Bush to rattle Dan Rather in a 1988 interview by bringing up an embarrassing moment the previous year when Rather had stormed off camera on live TV. “How would you like it if I judged your career by those seven minutes when you walked off the set?” Bush said.

That technique—talk in sound bites, go on the offensive, throw your moderator off his game—has since become standard operating procedure for politicians on the debate stage. The incident with Rather has eerie parallels to the Fox News debate this spring, when Ted Cruz started pummeling the moderators rather than his opponents, earning wild cheers from the crowd.

Trump has adopted some of these techniques: He talks in short, staccato sound bites and feuds with journalists who interview him. Last week, he labeled moderator Lester Holt a Democrat (the NBC newscaster has been a registered Republican since 2003, according to Time) and warned Holt not to correct him like Candy Crowley did Romney in 2012.

But Trump will need more than that to keep up with Clinton when they square off under the klieg lights at Hofstra University on Monday evening. Their speaking styles are as different as their politics: a great debater against a great evader. Clinton’s team reportedly has been pouring over old debate footage to find pressure points that Clinton can exploit to unnerve Trump. They have hired psychologists to analyze his personality and single out what most upsets him.

Ailes, however, may be able to help Trump turn the tables on Clinton. As Barnes wrote in 1988, “A business… leader who is friendly and at ease in conversation may tighten up in front of a TV camera.” That’s exactly what Trump struggles with. A few sharper lines, a stab at Holt, pithy jabs at Clinton for her health and penchant for privacy—and Trump could pull off an upset. If Trump takes Ailes’s advice to heart, he’ll be a debater to be reckoned with. And if Ailes can engineer the same wipeout he did in 1984 and 1988, Democratic operatives ought to be worried.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly named the moderator of Monday’s debate. It’s Lester Holt, not Jim Holt.