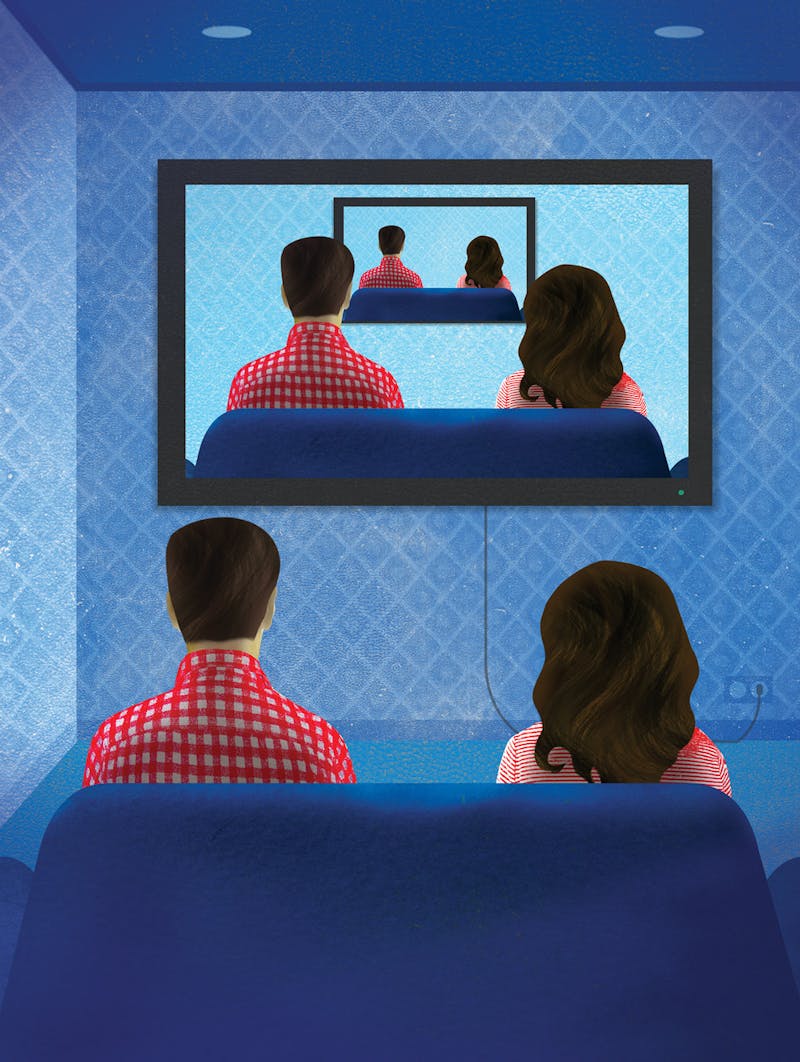

Marriage, plotwise, is usually the end of the story: happily ever after, roll credits. This began to seem absurd to me after I got married and realized that, lifewise, it’s just the beginning. Marriage, as it turns out, isn’t just a single decision, after which life unspools in a set course, but rather a series of constant negotiations, logistical rejiggerings, and identity crises. It’s easy to understand why these messy realities have, until recently, been hard to portray on television; the strictures of the 23-episode series, aired once a week for 30 minutes, used to require much simpler narrative structures. The couple was either at the center of a comedic universe, where story lines spun out from friends, work, and family, or they were the antagonists of a dramatic plot, tracing a path toward their permanent dissolution. Lately, though, a spate of new shows has blended both humor and pathos, telling at last a more complex story about contemporary marriage.

My partner and I are currently watching the most television we’ve ever watched together—we’re in the first year of our marriage, and of our son’s life. We’ve been drawn to these new shows because they’re awkward, flawed, and often sort of hard to watch, but in spite of or because of those factors, they’re just what we’ve needed. We flew through Togetherness, HBO’s recently canceled two-season comedy about an unhappy couple whose love competes with their ego-driven immaturity; binged on Catastrophe, the Amazon series in which a transatlantic fling results in a pregnancy and an impulse marriage; and devoured Divorce, Sarah Jessica Parker’s new HBO series that spins out one marriage’s murky ending. This trifecta of shows, when you say their titles in that order—togetherness, catastrophe, divorce—appears to tell a common story about what can happen to love when it’s domesticated. While the protagonists are still white, heterosexual, and upwardly mobile, there is something that feels modern about the way their relationships come together and fall apart—happy moments are shot through with a sad glance, arguments are never really resolved, and sex is for whenever you can get it. It’s hard to consider any of these shows outright “comedies”: Though some moments in each are out-loud funny, the stakes of what the failure of their relationships would mean to the characters are made clear in a way that keeps things remarkably tense and often incredibly sad.

The 1950s were a golden age for television, when American mythmaking about marriage was at its zenith. Though the “traditional” family of the time may never have really existed—social historian Stephanie Coontz calls the nuclear, middle-class, breadwinner-father-who-knows-best model “an ahistorical amalgam of structures, values, and behaviors that never coexisted in the same time and place”—it has continued to hold considerable sway in the world of scripted television. For more than 50 years, you were either in or you were out: A marriage was good and you preserved it, or it was bad and you dealt with it. But for the most part, the problems in sitcom marriages boiled down to a perpetual conflict caused by one character flaw per person, which was always resolved via indomitable, if improbable, sexual attraction—one never seen, but always present.

Sex is more explicit on these new shows, as is its use as a bargaining chip, communication medium, and weapon. Though the central couples on Togetherness, Catastrophe, and Divorce all live in different places and are at slightly different ages and life stages—Los Angeles, London, suburban New York; thirties, forties, fifties—their relationships are all tested by the same factors. All deal with the fallout from having children—how the personal and professional sacrifices of parenthood have deformed their identities, and how hard the struggle can be to get those identities back. Instead of asking whether a couple should stay together, these shows examine whether the shortcut of infidelity or the sloggier path of professional reinvention is a better way to reclaim a selfhood. What is forgivable, and what isn’t? What can a marriage survive, and what is an inevitable deal-breaker? Is sex something to crave, or is it something to be wielded?

Togetherness, created by Mark and Jay Duplass and Steve Zissis, which finished its second and final season earlier this year, traced the reinvention of Michelle (Melanie Lynskey) as she shook off the slog of early motherhood and tried to get back in touch with whomever she had been before marrying her husband, Brett, a sound engineer and kind of a putz.

Michelle escapes her domestic dead end by pouring her energy into a new charter school, an effort that’s initially channeled through her crush on a fellow crusader who’s a single dad. This leads to an infidelity that Michelle immediately regrets.

There’s enough nuance in Lynskey’s performance to allow for the possibility that, deep down, Michelle knows that her marriage is holding her back. Instead of simply making the case that what Michelle did was “bad” and focusing on her search for redemption, the show does a novel thing and treats her crush and its consummation as symptomatic of her search for purpose, which she later finds in a professional role at the school. Her marriage may survive, but it’s grounded on different terms than it was before she cheated.

Marriage is a near-constant shifting of terms in these shows, a gray zone I wasn’t familiar with growing up. I’d like to blame my lack of televisual role models for how benighted I was about what marriage truly entails. Still, it’s hard for me to remember why I wanted to get married. (I do remember I wanted to, so badly!) Part of it was that I found the idea of someone wanting to be married to me incredibly romantic and flattering. The wedding seemed like a magical spell that would render us greater than the sum of our parts. Now that I’m on the other side, my marriage isn’t bad—it’s even pretty good!—but my daily experience of it has nothing to do with these fantasies. It’s not like I hadn’t ever heard the truism “marriage takes work” before—I just had no idea what kind of work we were talking about. What sets apart the post-marriage plot on television is how determined it is to put that work on display.

Infidelity and identity play a slightly different role on Catastrophe, Sharon Horgan and Rob Delaney’s brilliant series about an Irish woman and an American man who meet, have lots of sex, and respond to a resulting unplanned pregnancy by making a precipitous and irrational decision to marry each other. While the first season merrily exploits the tension inherent in a forced, accelerated, and intercultural courtship, the stakes are still relatively low. But by the second season, they’ve got two kids, Sharon hasn’t found her footing in the social world of stay-at-home mothers, and Rob has taken a job he hates at an advertising firm that pimps unsavory pharmaceutical companies. They’re both adrift in a sea of responsibilities, clinging to each other, trying not to drown.

The pressure this puts on their relationship is summed up hilariously and all too realistically in a conversation that occurs at the end of what’s been a shitty day for both of them. Rob has been hit on by a beautiful co-worker, threatening his job and his fidelity; Sharon has been dissed by a former friend who, quite understandably, doesn’t want to waste her precious free time with someone so demonstrably needy. Sharon wants to talk, but Rob’s all out of empathy. The work day, the kids, “those things use up all my daily care units, so sometimes when you need attention at the end of the day, I’ve got nothing left for you.” Sharon smiles wide. “You dig deep and you scrounge something up for me. Don’t be lazy!” Because she manages to say this with an exasperated grin, and not cold rage, he does. Catastrophe is a portrait of a marriage as a machine, its inner workings always exposed, making up in functionality what it lacks in mystery. But Rob and Sharon are always honest with each other, often to a fault; neither of them knows how to be otherwise. And improbably, this is what keeps them together.

Frances and Robert, the couple at the center of Divorce—which is also co-produced by Sharon Horgan, and stars Sarah Jessica Parker—don’t even keep up a pretense of trying to understand each other after 17 years of marriage; when Robert tries to tell Frances the details about a house he’s renovating, you can see her eyes glaze over. Frances is stylish and serene, and seems unhappy in almost all realms of her life. She has a job as a corporate headhunter, which she took to support her husband while he flips houses, but her true dream is to open an art gallery—an occupation pulled from the “fictional character’s true dream” hat. She wishes her kids liked and needed her more, and acutely feels the sting of their age-appropriate rejection. When she has an affair with a goofy Columbia professor (Jermaine Clement), it only makes her feel worse about herself and her life; she realizes, after the fog of sexual attraction dissipates, that she has upended her world over a clownish person who makes his own granola and kombucha and doesn’t really like her much, anyway.

Robert, by contrast, seems like a constitutionally happy-go-lucky type of person, or at least someone who would be happy if only he weren’t trapped with a partner so unlike him. He’s a simple soul, habitually wearing a corduroy jacket and a flannel button-down, which he refers to as his “suit.” He has a moustache, which Frances complains is musty and perpetually somehow damp, and you believe her. He loves all-you-can-eat buffets.

The two are so dissimilar, it’s hard to imagine why they got married in the first place—but, as the show implies, it was so long ago that it almost doesn’t matter. In Divorce, marriage is a long accretion, the gathering of sediment year after year, until digging out becomes so much hard, horrible work that it’s no longer worth doing.

“We’re not like them, are we?” my husband asked after a few episodes. It was a relief to be able to say, definitively, “No.” I still want to do the work. On the other hand, who knows what the future holds for any of us? We watch these shows the way we spread dark gossip, as an inoculation against our worst fears about marriage and ourselves. These shows tell the truth about what happens in the months and years after the papers are signed, the wine is drunk, the guests scattered. It’s the plot with the well-defined beginning that spins out, doubles back, stops and starts, then relentlessly flows on. That these shows feel like a revelation is a measure of how infrequently this story has been told. It may not be pretty, but it’s riveting to watch.