During the 1970s, Grandmaster Flash found a way to jury-rig a turntable so he could listen to one beat while another record played over the speakers—now the standard cue function on mixers. Back then, many DJs made some kind of visible mark on a piece of vinyl to note where the beginning of a break was located. With a great deal of concentration, a DJ could return a record to the beginning of a break by looking at that mark, manually spinning the record backwards the right number of rotations, and then switching that turntable back on to play for the crowd, essentially flying blind and trusting that his eyes and muscles could keep two turntables alternating in time. When it was done correctly, dancers and wallflowers alike found themselves in a world where exclusive versions of songs were being created in real time.

As a 12-year-old kid living in Brooklyn in 1979, I fell instantly for “Rapper’s Delight,” but that didn’t mean it was clear what kind of music I was falling for. Since the entire backing track for “Rapper’s Delight” is the rhythm bed of Chic’s “Good Times,” I assumed it was a one-off, a “special” version of the Chic single. But then another rap song appeared, and another. It was unclear to my teenage brain how people were making new songs from bits of old songs. You were allowed to do that? But how? I began to hear people whisper about these “breaks” that stitched together one beat to another, but older Bronx natives called those sections “the get down.”

It’s a small difference, a quirk of geography. But before the internet, it was a genuinely long way from my home in Fort Greene to the South Bronx. Local vernaculars could be really local. This kind of attention to detail is what drives Baz Luhrmann’s exuberant, lopsided, and lavish Netflix series, The Get Down, which can’t possibly fall down every musical rabbit hole that New York in the ’70s had to offer, but certainly tries. Luhrmann and his large cast of advisers from this early age of hip-hop—many of whom also appear as characters in the show—have managed to make the world of the break seem as much fun as it did to this skinny kid from Brooklyn. It’s a minor thrill that the characters talk about stick-up kids and bullies as “hard rocks,” a term I did hear in Brooklyn, but have never heard in a TV drama.

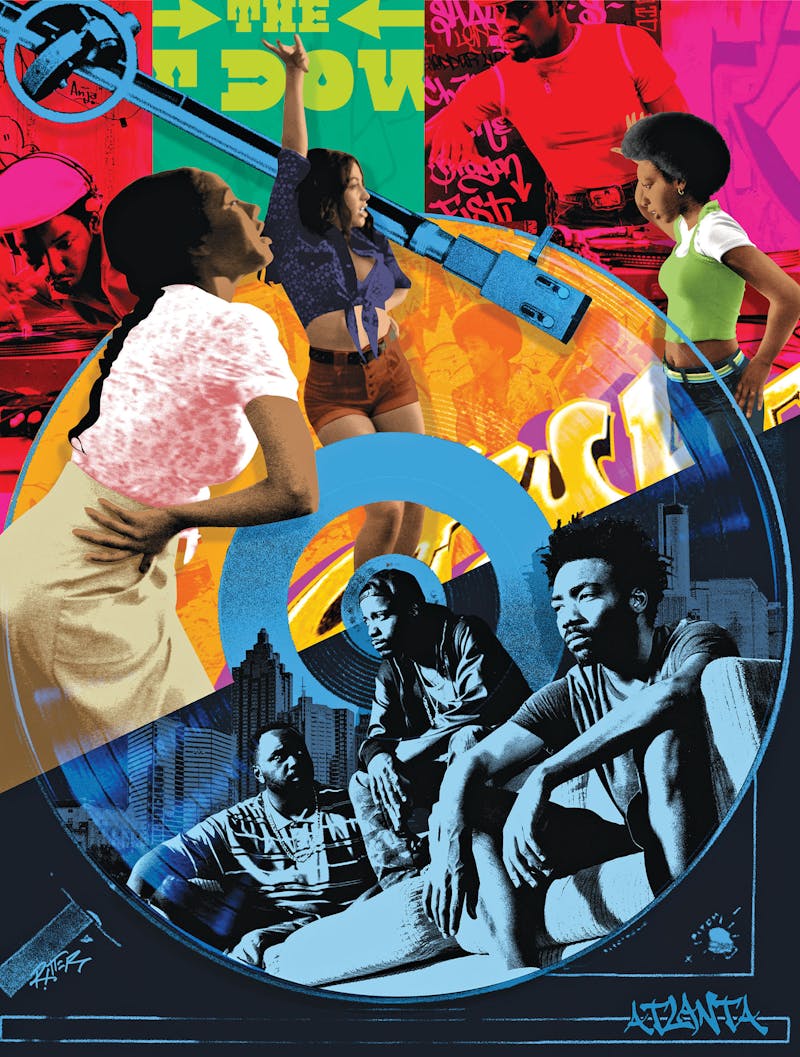

While The Get Down rockets through the Bronx in the summer of 1977, Donald Glover’s Atlanta slouches through the South of today. These two new shows bookend a 40-year period that has been defined by hip-hop, though they don’t see eye to eye on the power of music, socially or culturally. The executive summary is that both are careful, concentrated TV shows that work in very different ways: The Get Down is a whirling, saturated, fantasy-friendly “yes,” while Atlanta is a granular, stubbornly realistic “nah.” The former is a vivid history lesson about music—blend Scooby-Doo with Saturday Night Fever and you’re close to the tone—and the latter is a sharp, dark report about being young, black, and Southern in 2016. For The Get Down, hip-hop is a substance being mined and used to light up a city that, literally, goes pitch black. In Atlanta, the lights are just off. Even Paper Boi, an aspiring rapper and one of a trio of friends who anchor the show, doesn’t think the music he’s making is going to help him launch a career: “There’s no money anywhere near rap.” In 1977, hip-hop was a way to play with the fabric of time. In 2016, it’s just another way to kill time.

Baz Luhrmann would not have been my first, third, or tenth choice to direct a show about how hip-hop, disco, and Ed Koch all handled New York in 1977. As a director, his production design is unmatched; as for making the parts of the film that transmit narrative, I have found most of his decisions almost unwatchable. His recent adaptation of The Great Gatsby may or may not have addressed Jay Gatsby’s hubris, but I couldn’t tell you for sure, as the movie continually had me one more goddamned zoom-shot away from a seizure.

In The Get Down, characters sometimes talk in rhymed dialogue, like refugees from Luhrmann’s adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, and expository phrases float by like burners on the sides of subway cars. But somehow, television has turned Lurhmann’s frantic visual hunger into exuberance. Perhaps credit should go to a cast of advisers and producers that includes Nas, Grandmaster Flash, Kurtis Blow, Rahiem of the Furious Five, and journalist Nelson George, one of the few people to know hip-hop and film equally well. This cabinet of consiglieres may explain how someone who didn’t grow up in the city, or the era, could get so many things right. With its frenzy filtered over six hours, The Get Down feels wired.

Earlier this year, the HBO miniseries Vinyl took on the same assignment as The Get Down: Pick an era (the East Village punk scene in the ’70s), gather a parade of famous musicians (Janis Joplin, Alice Cooper, the New York Dolls), and plant a fictional protagonist in the middle (Bobby Cannavale’s venial record producer). Martin Scorsese, Mick Jagger, and their collaborators knew their onions, or grew them—but Vinyl would not likely make any teenager dig out a Ramones album, or search YouTube for live Sex Pistols footage. Scorsese’s taste for slow, magisterial sweep didn’t suit the story of bands that valued speed and impact over precision, and that didn’t mind some dirt in the gears. The Get Down matches its imagery to the pulse of the music—it’s plausible that a teenager would end up mauling her parents’ turntable trying to learn how to beat-juggle like Grandmaster Flash. Unlike the drug-addled population of Vinyl, the kids in The Get Down make the challenge of creating a new music from pieces of the old look like fun.

The show’s scrawny hero, Ezekiel, a.k.a. “Books,” is played by Justice Smith with a charming blend of teenage jitters and bravado. Books is something like the Grandmaster Caz of his day, writing rhymes for everyone around him, as well as himself. Sometimes his cadence sounds more 2016 than 1977—more Nas than Rahiem. At the time, getting everything to work together in strict time was the first goal; virtuosic rhythms were a decade away, as was sampling. But such missteps are few: Books and his Get Down Crew sound like they would have ended up on Enjoy or Sugar Hill. They compete against a variety of crews that spring up quickly across the Bronx. Books’ love interest, Mylene, lives under a religious house arrest with her parents, but her dream is to become a disco diva like her fictional hero Misty Holloway.

Lurhmann’s ’70s South Bronx does a good impression of the actual ’70s Bronx. Manfred Kirchheimer’s Stations of the Elevated, which followed graffiti artists as they tagged subway cars in 1977, captured kids jumping out of abandoned buildings onto mattresses. Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant’s Style Wars, which covered both taggers and break-dancers, contains footage of the legendary graffiti writers’ bench at the 149th Street–Grand Concourse stop that Luhrmann recreates (sort of) in The Get Down. The show is careful to avoid the clichés of urban decay that have plagued almost every story of hip-hop. The protagonists of The Get Down spend as much time hanging out in St. Mary’s Park as they do in the crew’s monastic squat.

It’s hard to imagine such crews surviving for long in the real world, because historically, they didn’t. Disco was over in a few years and early hip-hop labels were notoriously unscrupulous. “I don’t think the true Sugar Hill Records story has ever been told,” Sugar Hill house drummer Keith Le Blanc once said, “because there’s so much skullduggery attached to it.” It’s a sentiment that Q-Tip summed up in a lyric: “Industry rule number four-thousand and eighty / Record company people are shady.”

The characters in Atlanta don’t need to be told any of this. Paper Boi (Brian Tyree Henry) is launching his own low-budget rap career, managed by his drifting cousin Earn (Donald Glover), while already not believing such a thing exists. Glover—who created, wrote, and directed several episodes of the show—knows the industry firsthand. After a first career as a writer for 30 Rock and a second career on Community, for his third career he released two albums as Childish Gambino. As a performer, Glover staked out the territory that Chance the Rapper now occupies: streetwise but legal, sweet but not dumb. Paper Boi is nothing like Gambino and Chance—he’s more in the vein of Atlanta rappers like Migos, who appear in the show briefly. Rhymes can be simple and repeat ad infinitum: The appeal is all in delivery and tone. Glover’s own rhymes exhibit a faith in wordplay and literary turns, a taste that is becoming something of a generational divide. Though not Chance’s equal as a rapper, Glover’s Gambino deserved a better shake than he got from hip-hop fanatics, an unforgiving community.

Atlanta may be Glover’s revenge—it’s his best work yet. It’s low-key enough that it may not get the panopticon treatment The Get Down enjoys, but it is more suited to a long series run. If The Get Down is the spiritual heir to Wild Style, Atlanta is a spin on the post-Girls sitcom. (Glover appeared briefly on that show as a well-meaning Republican boyfriend.) It’s a comedy that’s as likely to stress the difficulty of paying for a restaurant meal as to go for a laugh, and things generally don’t work out for the show’s small group of friends, none of whom show their cards quickly: Earn is a Princeton dropout trying to win back the mother of his child; Paper Boi is navigating his rap career; and Darius deals drugs in a utilitarian, unflashy, day-job style. The tone of the show is solidly deadpan—Glover has described it as “Twin Peaks with rappers”—which becomes increasingly useful as the season unfolds.

The characters are more like witnesses to their world than participants, which would be dull if Glover wasn’t so good at capturing the fine detail of people’s blockheaded moments. In one episode, Earn and Paper Boi encounter Zan, an internet addict who does everything for the Vines. To him, all footage is simply good, an opportunity for likes. When he mocks Paper Boi on his YouTube channel, he sees no cognitive dissonance in later running into Paper Boi on the street and inviting him to ride along as he delivers pizzas. Zan then films a young boy delivering a pizza and getting stiffed, which he visibly enjoys, ignoring the kid’s distress. It’s a masterful skewering of online personalities. If Glover wants to take his band of human shruggies around town as they bear witness to the glorious rainbow of modern stupidity, I will happily ride along. The Get Down scratches an admittedly nostalgic itch, like a parade for my youth. But who ever watches a parade twice?