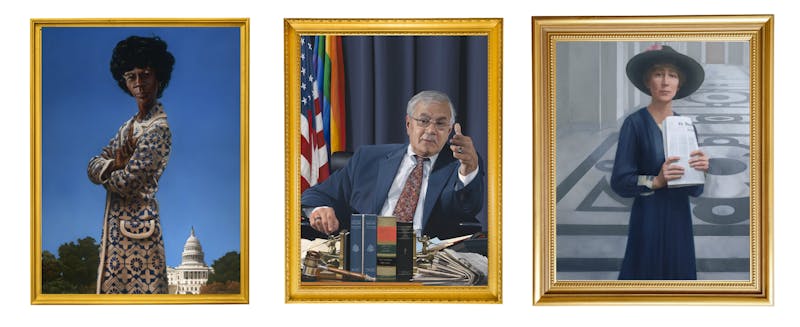

In the halls of the U.S. Capitol hangs a portrait of Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman elected to Congress, and the first woman, and major-party black candidate, to run for President. Chisholm represented New York’s 12th congressional district in the House for nearly 15 years; previously she had served in the New York State assembly, where she was only the second woman of color to do so. Known as “Fighting Shirley,” the portrait shows her as nothing less than fearless: Chisholm stands in the middle of the frame in her signature horn-rim glasses and a brocade coat, arms crossed as she towers over the U.S. Capitol, a clear blue sky behind her. Painted by Kadir Nelson, the artist responsible for the artwork on the cover of Drake’s 2013 album Nothing Was the Same, it’s hard to imagine that Chisholm wouldn’t have approved. However, we’ll never know what Chisholm thought of her official portrait; she died in 2005, four years before the painting was unveiled.

Oil portraits like Chisholm’s are usually reserved for Speakers of the House, committee chairs, and other federal leadership positions—Former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta unveiled a portrait last year that included his dog to represent loyalty—but the History, Art & Archives department of the U.S. House has previously held competitions for portrait artists to paint the images of the women and people of color who have been historically underrepresented in government—and thus, underrepresented in the House portrait collection.

Other branches of the U.S. government are also now realizing that it’s time to recognize these underrepresented patriots. Last week, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew announced plans to add Harriet Tubman, Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Eleanor Roosevelt, Martin Luther King Jr., and other suffragists and civil rights leaders to multiple U.S. bills. The announcement is historic: It marks the first time a woman or person of color will appear on a bill that is routinely used—Anthony has already appeared on the dollar coin, and so has Lewis and Clark guide Sacagawea—but while the Treasury clearly has the budget to implement these kinds of revolutionary redesigns, the House Art department will no longer have the same option.

Last February, after adding temporary bans on federal funding for oil paintings to each annual budget since 2014, Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) finally succeeded in enacting a permanent ban on using federal money for official portraits. His bill, the Eliminating Government-funded Oil-painting Act—known by its intentional acronym, the EGO Act—is based on the belief that taxpayer money should not be spent on superfluous artwork to commemorate service to the federal government. “In response to lavish spending on portraits for government Officials,” the bill enumerates various offenses:

$22,500 by the United States Department of Agriculture for a portrait of Secretary Thomas J. Vilsack ... $40,000 by the United States Department of Justice for a portrait of former Attorney General John Ashcroft ... $46,790 by the DoD for a portrait of the former Secretary of Defense, Donald H. Rumsfeld, his second official portrait bought by the American taxpayers.

Although a government study shows that the bill will save less than $500,000 annually, with an average cost of $25,000 per portrait it’s easy to see how oil paintings became a target of politicians bent on curbing government waste. But although some people, like Tax Payers for Common Sense spokesman Steve Ellis, think that a selfie is a suitable replacement for oil portraits, nothing could be further from the truth.

Looking through the House and Senate portrait collections, you’ll find a wealth of white legislators in ill-fitting suits posing awkwardly among symbolic objects: dogs, children, clocks, gavels, and flags—lots of flags. The portrait of Representative Dave Obey (D-WI), completed in 2005 (six years before his 2011 retirement), is so crowded with allusions that it resembles an inanimate haunting: a set of books, remnants of a mirror, the state of Wisconsin, and a ghostly portrait of the state’s beloved governor and senator Robert La Follette float alongside the congressman. If this was the first portrait that you saw from the congressional collection, you might agree with Senator Cassidy that the endeavor to memorialize congressmen in oil paintings is a complete waste of money.

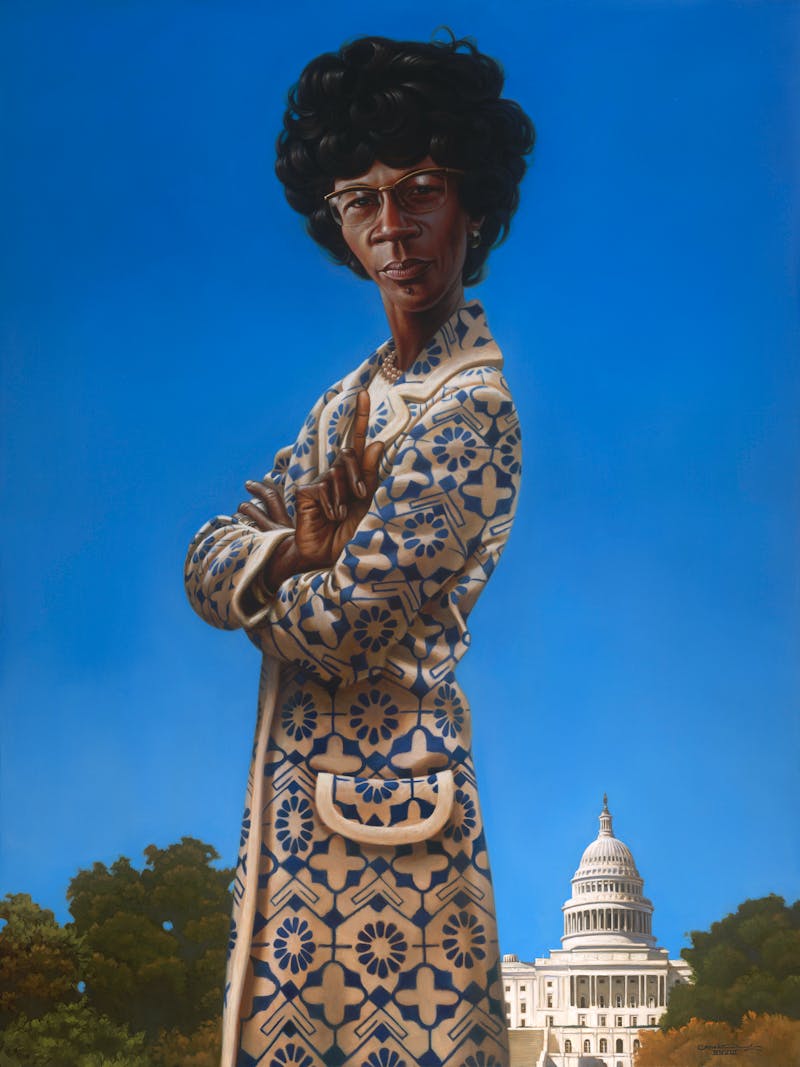

But dig a little deeper, and you’ll find images that could never have existed without the medium. In his portrait, Representative Barney Frank (D-MA) sits in front of both an American flag and a gay pride flag, brusquely gesturing at someone behind the viewer. His desk is a mess of newspapers and bills, although the directories from his Congressional terms stand neatly in the middle. Still closeted when he began his first term in the House, Frank overcame a public outing and prostitution scandal, won re-election, and continued to serve as a congressman for over 20 years. The portrait was completed in 2013, the same year as Frank’s retirement. The inclusion of the pride flag symbolizes more than Frank’s support for gay rights; it represents his personal struggles as well.

But if you’re not a white man, gay or straight, good luck getting a portrait painted before you die. The first Asian American in congress, Dalip Singh Saund (D-CA), served as a representative for four years until a stroke ended his political career in 1962. Saund had come to the U.S. by way of Ellis Island and earned both a M.A. and PhD in mathematics from the University of California-Berkeley. He was instrumental in the fight to allow South Asians to become naturalized citizens; Saund himself did not become a citizen until 1949. Saund died in 1973, but his portrait wasn’t commissioned until 2007, over 40 years later, and it shows him standing in the Capitol rotunda, bordered by the places and people that influenced his career: India, California, Gandhi, and Lincoln.

Representatives like Shirley Chisholm get an even worse deal: Already a minority in Congress, few women are committee chairs or other types of congressional leaders—a prerequisite for most of the portraits in the House and Senate collections. It took six congresswomen to lobby for a portrait of Jeanette Rankin, the first woman to serve in Congress.

In 1916, when Rankin was elected, she couldn’t even cast a ballot for herself, and her portrait is an incredible representation of the isolated nature of her first term: Rankin stands in an empty marble hallway, clutching The Washington Post edition that announced her swearing-in on its front page. Her somber navy dress and black hat are brightened by a solitary pink flower on top—standing in a hallway of Congress, she looks very much alone.

According to painter Sharon Sprung, this solitary feeling was intentional. Sprung won a competition put on by the House Art Department, which was looking for painters to create images of the first female, Hispanic, and Asian members of Congress. Sprung worked closely with the curatorial staff at the House to conduct research in preparation for the project, visiting a costume house to get a period dress and hat, and also obtaining the newspaper printed on Rankin’s first day in Congress.

Sprung estimates the cost of the portrait was between $35,000 and $50,000, 40 percent of which went to her gallery. Although that figure might sound high, the commission was also months and months of work and Sprung says the meaning behind it more than justified the cost, as portraiture “gives you entrance into a way of life. It gives you a different knowledge of the person to see it visually.”

Supporters of the EGO Act may think that a selfie is a perfectly reasonable substitute for detailed portraits. But to depend on photography, for one, requires us to remember to take photographs other than the ones that are used for U.S. Capitol ID cards. Even as photography has become the default medium for capturing events, photographic portraits—with bland backgrounds and frozen smiles—fail to hold the viewer’s eye like a detailed painting can. The photographs available in the House Archives are certainly historic, but the most interesting are not the portraits of legislators, but the ones that capture speeches on the floor of Congress or senators in Selma, Alabama. Although Sprung agrees that photography has its place in memorializing events and people, she doesn’t believe it can take the place of painting. “A photograph captures a moment,” Sprung said, “but a painting you work on for months, you do tremendous research. There’s so much involved every day in capturing the nuance of a lip and just changing it, or the look of an eye. There’s such a subtlety in the expression and it’s the layers of expression that really change it.”

Although the EGO Act bans federal funding for oil paintings, it doesn’t ban the existence of oil paintings in the House and Senate collections. Private funding is often used to commission portraits, and presidential and vice presidential portraits are paid for by a separate White House fund. But private funding isn’t a panacea either, according to Sprung, “When a curatorial staff commissions something, they’re historians. So they really understand what’s important and the story they need to tell with that. When you have a constituency that donates money for a portrait, it’s a really different thing because they have a completely different agenda.” Without the federal funding for oil portraits, posthumous paintings of the women and people of color who shaped the federal government will become even more difficult.