Nobody swears like Selina Meyer, though sometimes I wish someone would. Veep, currently entering its fifth season, is by now rightfully famous for the care with which its writers treat their characters’ obscenities: Every vulgarity in the script is confected with the precision of a perfect, vile truffle. But Selina Meyer, played by Julia Louis-Dreyfus, might just best them all. She can switch from telegenic radiance to ferocious crudeness in a heartbeat, in the same way that she can charm someone for whom she feels nothing but loathing. In other words, she’s very, very good at what she does.

Meyer was the vice president at the start of the series, became president in season three, and now, as the fifth season opens, she inhabits an unprecedented nether zone following an election-night tie—“Didn’t those Founding Fuckers ever hear of an odd number?” she asks of the Electoral College. Selina’s greatest talent might be her instinct for camera-readiness; it might also be her greatest fault. Veep is a deliciously well-crafted comedy, but there has always been something terrifying about it, too: As we laughed at the hollow antics of imaginary politicians, we had to wonder whether the real ones acted this way.

Perhaps the better question is what the concept of “real politicians” means anymore. The fifth season of Veep takes place in a political landscape outlandish enough to defy even the vision of creator Armando Iannucci, who stepped down as showrunner after last season. In her struggle to reach the White House, Selina had to pit herself against a staid military man, a blowhard war hero, a dark horse baseball coach, and an archconservative Boss Hogg lookalike. Even this pool seems enviable when compared to the one the American people face today. Veep began as a biting Beltway satire, but the results of the next election may render it disconcertingly utopian.

The last season of Veep ended on a cliffhanger, and the new season doesn’t rescue audience members from the ledge. Selina and her staff are, at the start of season five, scrambling to see how the election-night tie will be resolved, and scrambling in slow motion at that. In the first episode, Selina’s strategy boils down to yet another ratings game: Her most important task is “to look as Presidential as possible.” (In a subplot that would give Aaron Sorkin an embolism, Selina’s stress pimple gets a parody Twitter account, which quickly gains more followers than her own.)

Veep has mined some of its most devastatingly funny and purely devastating material from the moments in which Selina finds herself forced to act not like a politician—endorsing whatever belief she needs to in order to win—but like a human being who might have beliefs of her own. In season three’s “The Choice,” in which Selina has to announce her stance on abortion, her staff spends the entire episode figuring out how to say something while essentially saying nothing. The fear of alienating voters keeps her from saying anything definitive about abortion; it also leads her to treat her own gender as the kind of toxic secret best addressed by a don’t-ask-don’t-tell policy. All it takes is one of her male staffers suggesting that she begin her statement with the phrase “as a woman” to unleash one of Selina’s most despondent rants: “I can’t identify myself as a woman,” she says. “People can’t know that. Men hate that. And women who hate women hate that—which, I believe, is most women.”

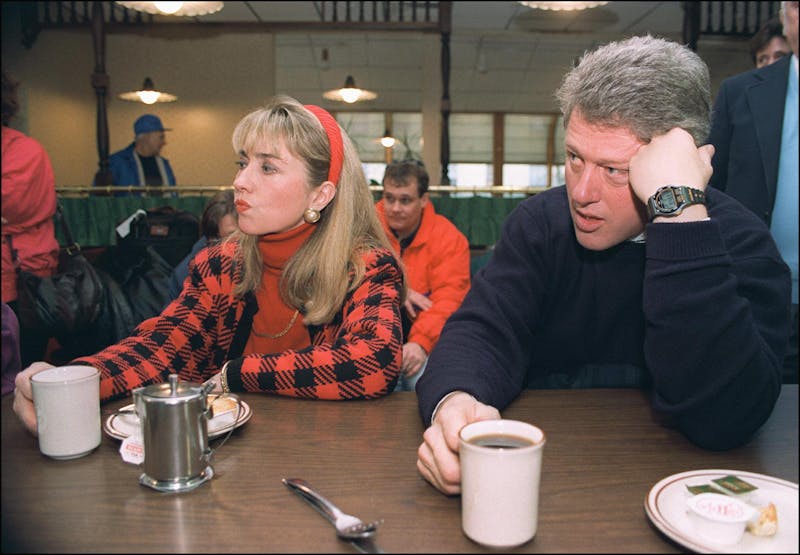

Perhaps more than anyone else in America today, Selina’s real-life counterpart, Hillary Clinton, understands the pitfalls of identifying herself as a woman. In the early 1990s, Hillary’s femininity—to say nothing of her feminism—was reason enough for countless Americans to ignore her opinions. Now, as she attempts to lay claim to her status as a female politician, she finds herself swimming against the tide of public opinion yet again. “Senator Sanders is the only person who, I think, would characterize me, a woman running to be the first woman president, as exemplifying the establishment,” Clinton said during her debate against Sanders in New Hampshire. The backlash was formidable. In 1992, Hillary Clinton couldn’t be a real politician because she was a woman. In 2016, Hillary can’t be a real woman because she is a politician.

It’s hard to talk about Selina without talking about Hillary. Like Selina, Hillary is a Washington “insider,” and a politician whose relationship with her public is based on decades of hard experience. Like Selina, Hillary has also been pilloried for her centrist leanings, her apparent willingness to change positions for the sake of political expediency, and her skill at playing ball with the boys.

Today, it’s difficult to remember that in 1992 Hillary Clinton was Imperator Furiosa. That was, at least, how the American public—to say nothing of the Washington “insiders” she now symbolizes—treated her. “The most controversial figure of the election year so far has been a woman,” Gail Sheehy wrote in Vanity Fair in May 1992. “She isn’t even running for office. Or is she?”

Something about Hillary Clinton struck fear into the hearts of not just conservative politicians, but journalists, commentators, and voters. She took an active role in her husband’s campaign! She spoke up for him! She spoke up for herself! During the election, she ignited a national controversy when she defended her career by saying, “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was to fulfill my profession, which I entered before my husband was in public life.” The response, Sheehy wrote in Vanity Fair, “offended millions of women who have chosen to be full-time homemakers.”

Election year sexism is subtler these days, maybe because it can no longer be directed at a single figure. But the criticism Hillary Clinton receives today still echoes her detractors’ claims from nearly 25 years ago. “When the cameras dolly in,” Sheehy wrote, “one can detect the calculation in the f-stop click of Hillary’s eyes… the public smile is practiced; the small frown establishes an air of superiority; her hair looks lifelessly doll-like.”

In 1992, there was something threatening about a woman being unapologetically strategic in her approach to politics: with whom she could ingratiate herself and for how long, how much power was there for the taking, and how she could get her hands on it. Perhaps there still is. But regardless of the state of sexism in American politics, the public’s discomfort with Hillary Clinton has to come, in part, from the disturbing knowledge that we made her this way. We created a world where a female politician could not speak openly about loving her career without being treated as a traitor to her sex, and when the First Lady couldn’t be too outspoken about her husband’s policies without being suspected of staging a coup.

If Hillary Clinton ever had the potential to interact with the American public in a genuine and unguarded way—let alone to harbor radical notions—the public taught her just how dangerous that was decades ago. By the time we meet her, Selina Meyer has learned the same lesson. In its quieter moments, Veep is not just a wickedly funny comedy, but a stinging depiction of the impossible predicament in which female politicians find themselves: You play the game, until the game plays you.

It’s easy to see how the fifth season could draw out Selina and her staff’s mad dash to regain control of the presidency, and probably with delectably painful results. Veep has one of the best ensemble casts on television today, and rarely uses it to greater effect than when it plays one character’s hysteria, confusion, and fury off the others’. Yet, as we approach our own election night, it’s hard not to wonder what Veep would be like if Selina found herself securely ensconced in the Oval Office. The show has brilliantly depicted the pain and compromise and pointless sacrifice politicians put themselves through in the pursuit of ultimate power. What would Selina do if she finally had what she wanted? Is the answer one we are ready for?