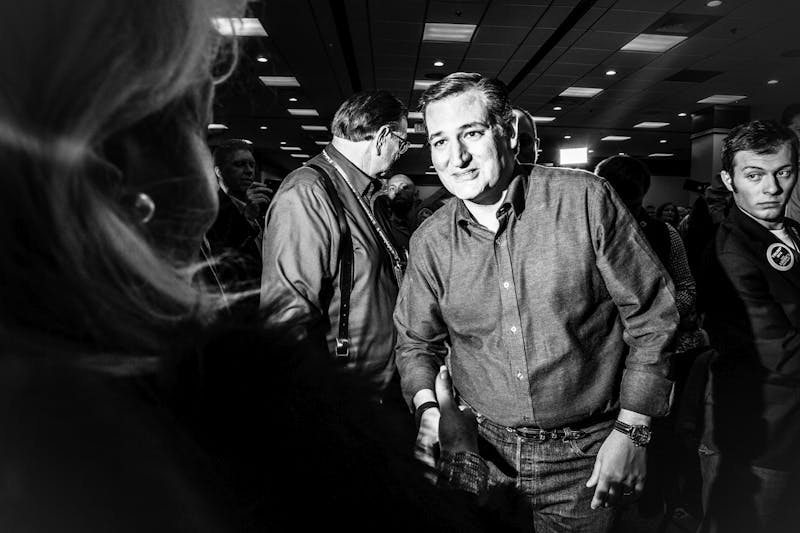

Ted Cruz couldn’t take it any longer. It was July 23, 2012. Houston. The final debate of the Republican runoff in Cruz’s bid for a seat in the U.S. Senate. The former Texas solicitor general had entered the race as a footnote, his polling in the low single digits, his political résumé extremely thin. Ted who? But over the course of 18 months, the little-known corporate litigator had caught fire with the Tea Party faithful, snagging endorsements from Sarah Palin and FreedomWorks, upending every expectation about his chances except his own. Now he stood on the cusp of one of the great upsets in Texas political history.

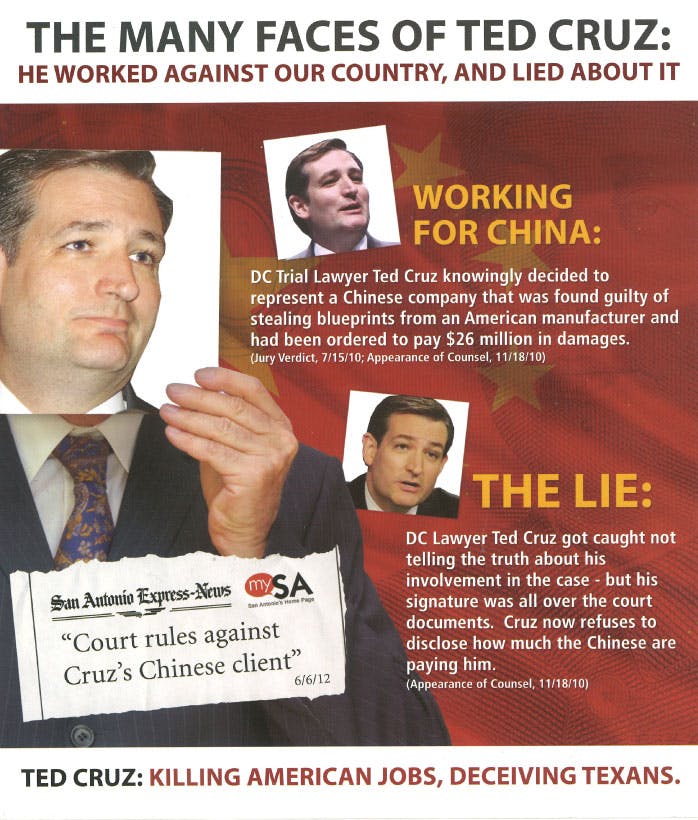

The debate moderator played a video question from a voter: “Why are they fighting so much?” Cruz turned to his opponent, three-term Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, a soporific millionaire who’d begun the race as the odds-on favorite but had underwhelmed and failed to avoid a runoff. As the summer had worn on and his numbers sagged, Dewhurst and his allies had tried to paint Cruz as a “D.C. insider,” a “conservative phony,” and a supporter of “amnesty for illegal immigrants.” Cruz had largely ignored Dewhurst’s salvos, though groups supporting his campaign had flung some insults about Dewhurst being a “Republican in Name Only.” But Cruz was particularly galled by his opponent’s latest hit. The week of the debate, a mailer had landed in mailboxes across the state—including that of Cruz’s father, Rafael—highlighting how Cruz, as an attorney, once defended a Chinese company accused of stealing blueprints from a U.S. manufacturer. The mailer branded Cruz a “D.C. trial lawyer” and accused him of lying about his work on the case. “Ted Cruz: Killing American Jobs, Deceiving Texans,” it read.

Cruz, full

of indignation, pulled a copy of the mailer from his pocket. “One of the worst

things you can say in politics is to malign someone’s patriotism,” he said,

“and yet what the lieutenant governor sent to my father was a mailer that said,

quote, ‘Ted Cruz worked against our country.’” The attack failed, of course.

Cruz bested Dewhurst in the runoff, coasted through the general election, and headed

to Washington to further torment the establishment and lay the groundwork for a

presidential bid.

Almost two years after that debate, in the spring of 2014, the man who produced the “un-American” mailer arrived at a townhouse not far from the U.S. Capitol. Jeff Roe had spent the previous decade in Kansas City, building his own mini-political kingdom and earning a reputation as one of the sharpest and meanest operatives in the business. The 43-year-old had dreamed of running a presidential campaign ever since he got his start in politics in rural Missouri. Now, behind those townhouse doors, awaited a candidate set to interview Roe for the chance to land just such a job. This candidate also happened to be the same man whose career Roe had sought to end before it began: Senator Ted Cruz.

It was a Tuesday, and Cruz had votes in the Senate. Roe was told he had an hour to make his case. The two men ended up talking for three and a half. Even setting aside the whole Cruz-is-un-American thing, Roe wasn’t an obvious choice to join Cruz’s team. He had no personal connection to the candidate. He’d worked only on the periphery of a couple of presidential campaigns—Mike Huckabee in 2008, Rick Perry in 2012. He’d never even managed a winning statewide race.

Roe knew Cruz was his guy. He had studied practically everything Cruz had ever done and said. Both men believed that politicians too often waffled in the face of opposition, and failed to deliver on what they promised to their strongest supporters. “It pisses me off,” Roe told me recently. Politicians, he said, leave voters “behind, they take them for granted. Because of that, less and less people participate in the system because their values continue to get trampled and they don’t feel like there is an outlet for them to do anything about it.”

Roe also pitched himself as singularly qualified to run Cruz’s presidential bid, touting a pedigree few, if any other, operatives had—how he’d built his own full-scale political operation from scratch, with multimillion-dollar budgets, dozens of employees, running everything from TV to direct mail, fund-raising, polling, research, strategy. And he was ready to put the whole thing on pause and move to Houston for Cruz—to go all in.

Cruz already knew what else he’d be getting: A master of hardball politics whose attacks could get under even the toughest politician’s skin—his own included. Maybe that’s why Roe’s mailer never came up in the conversation. Even so, Roe left the interview uncertain: “I walked out and I had no idea.” Three days later, he got the call. He was hired for the Cruz team, and would later be named campaign manager.

Smash cut to the start of 2016. Cruz is soaring. He leads the Republican presidential field in Iowa heading into the opening contest, and appears poised for a dogfight to the end with Donald Trump for the nomination. He’s risen by running a vintage Jeff Roe campaign: obsessively disciplined, well-funded, laser-focused on the base. Cruz has played up his ideological purity and sought to coalesce Republican base voters behind his candidacy. “Jeff has a simple philosophy,” said Brad Lager, a former Missouri lawmaker and good friend of Roe’s. “He believes that in order for someone to become president in this country, it’s not about motivating the middle. It’s about motivating your base.”

The Cruz campaign’s success so far confirms what many people who’ve watched Roe’s ascent have been saying for years. “I’ve believed for some time that Jeff Roe is a Karl Rove-level political talent,” said Gregg Keller, a former executive director of the American Conservative Union. “I’ve done four or five presidential campaigns. I’ve run campaigns in virtually every state in the country. And I have not come across an operative of my generation who I believe is more talented than Jeff Roe.”

The canny strategy and smooth, on-message operation of the Cruz campaign have gotten plenty of attention. But the man behind it has not. He prefers it that way. Out on the trail, Roe generally sticks close to the Cruz campaign bus rather than follow his candidate into small-town coffee shops and local libraries. When he does venture off the bus, though, you can’t miss him. The guy’s big, all gut and jowls, resembling a political cartoonist’s idea of a fat cat, but dressed in jeans and an oversized “Cruz 2016” fleece. He has a thin goatee, a gelled flick of hair, and thick hands often wrapped around an empty soda bottle for catching the spit juice from his beloved Red Man Golden Blend chewing tobacco.

What we’ve yet to see in this campaign is Roe’s other trademark attribute: the brass-knuckled approach to winning that’s made him many enemies. From his earliest days running state and local campaigns, he’s taken a scorched-earth approach to politics. Roe and his tactics have been blamed for damaging opponents’ lives and reputations, and even for contributing to a gubernatorial candidate’s suicide. (Roe doesn’t exactly hide from this reputation: His web site features headlines describing him as “ruthless” and a “leading practitioner of hard-ball politics.”)

On an early January swing through Iowa, Roe tended to linger at the crowd’s edge or at the back of whatever room he was in, studying the size of the crowd, monitoring his Blackberry. That’s where I found him during a Cruz stump speech in Spirit Lake, Iowa, standing near the untouched salad buffet at a Godfather’s Pizza. For weeks, I’d gotten nowhere emailing and calling Roe for an interview. He grimaced at hearing my request in person, but then spoke to me for a while, staying off the record. (We would subsequently talk twice more in person and twice by phone.) In recent months, I’ve also interviewed more than 30 of Roe’s friends, past and present colleagues, and candidates who’ve tangled with him in the past.

The portrait that emerges is of a sleepless, methodical operative—“machine-like,” as a former client put it—who has made himself into the quintessential Svengali of our money-drenched, hyperpolarized era. You could form a support group with all the scarred and embittered candidates out there, Democrats and Republicans alike, who’ve ended up on the wrong side of Jeff Roe. “He’s the best of the worst,” said one Kansas City Republican who was beaten by a Roe client. “The guy’s a scoundrel—and probably worse,” said a Democrat who ended up on the wrong side of Roe. “Be careful,” said another Democrat when I told her I was writing about Roe. “He’s dangerous. Call your mom. Tell her you love her.”

Roe’s story begins in the muck. He grew up in sleepy northern Missouri, a few hours outside of Kansas City, raised by his parents and working on his grandparents’ nearby farm. Roe helped raise pigs, tend cattle, and harvest corn and soybean. His grandmother, a Goldwater Republican, took him to local GOP fund-raisers and candidates’ speeches when they stopped in town; she instilled in him a strong sense of individualism, the belief that government shouldn’t do anything you can do for yourself. His grandfather, meanwhile, taught Roe the lessons he still lives by. For example: “When it’s raining, put a bowl on your head”—in other words, when business is good, get as much of it as you can. At 17, Roe enlisted in the Army National Guard, joining the Thirteen Bravo cannon crew and training to operate howitzers at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Today he likens the experience to politics—an ideal howitzer crew would have ten guys, but they had to learn to fire with six, and a short-staffed political campaign has to adapt in the same way.

Roe’s Greatest Hits

Jeff Roe has carved out a reputation as the go-to consultant for tea partiers, die-hard conservatives, and candidates willing to hold their noses and win ugly. He and his team at Axiom Strategies are also known for their—shall we say—creative license. Here’s a short highlight reel of Roe’s most impactful spots.

Roe’s firm, working for Republican Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, took aim at his long-shot primary challenger, Ted Cruz, in this mailer that conveyed one of the nastiest charges leveled against Cruz in his short career. But it couldn’t save Dewhurst.

The attack ad that put Roe on the map was aimed at Kay Barnes, a strong Democratic challenger to Roe's first boss, Congressman Sam Graves. The spot was slammed as homophobic and borderline racist. But it worked.

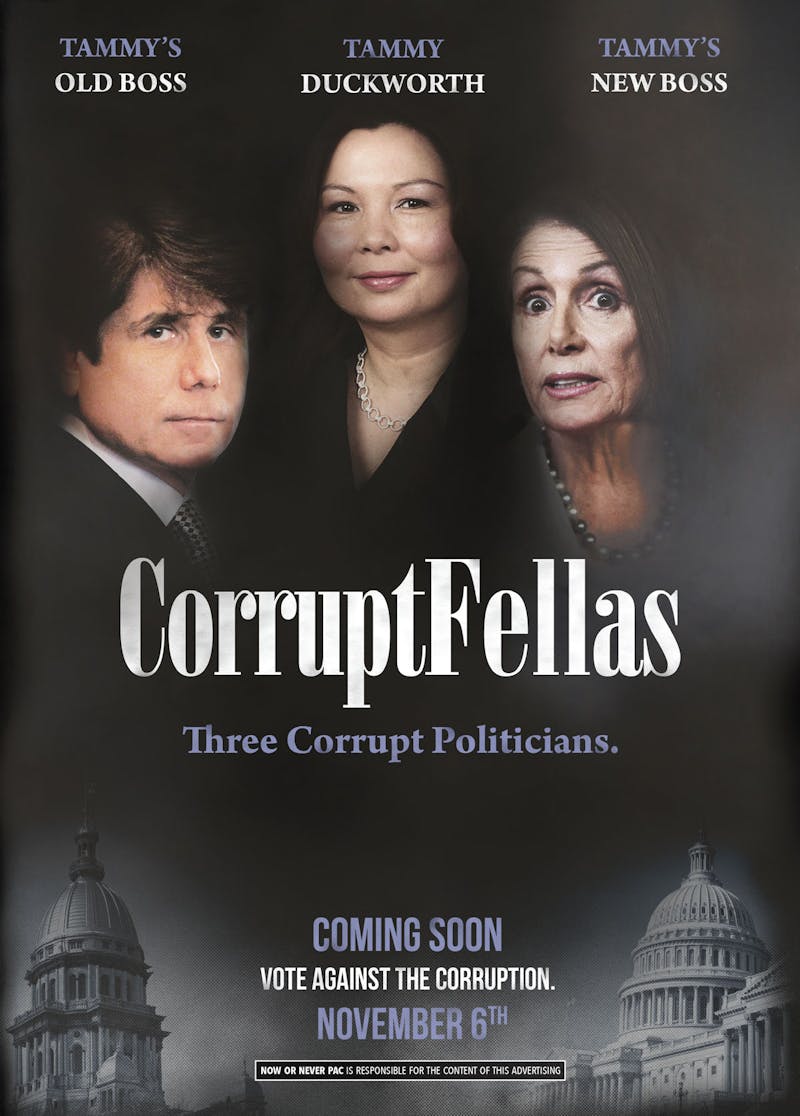

This Goodfellas parody tied Democratic Representative Tammy Duckworth to both indicted former Governor Rod Blagojevich and Nancy Pelosi. It won a Pollie award from the American Association of Political Consultants, but Duckworth survived.

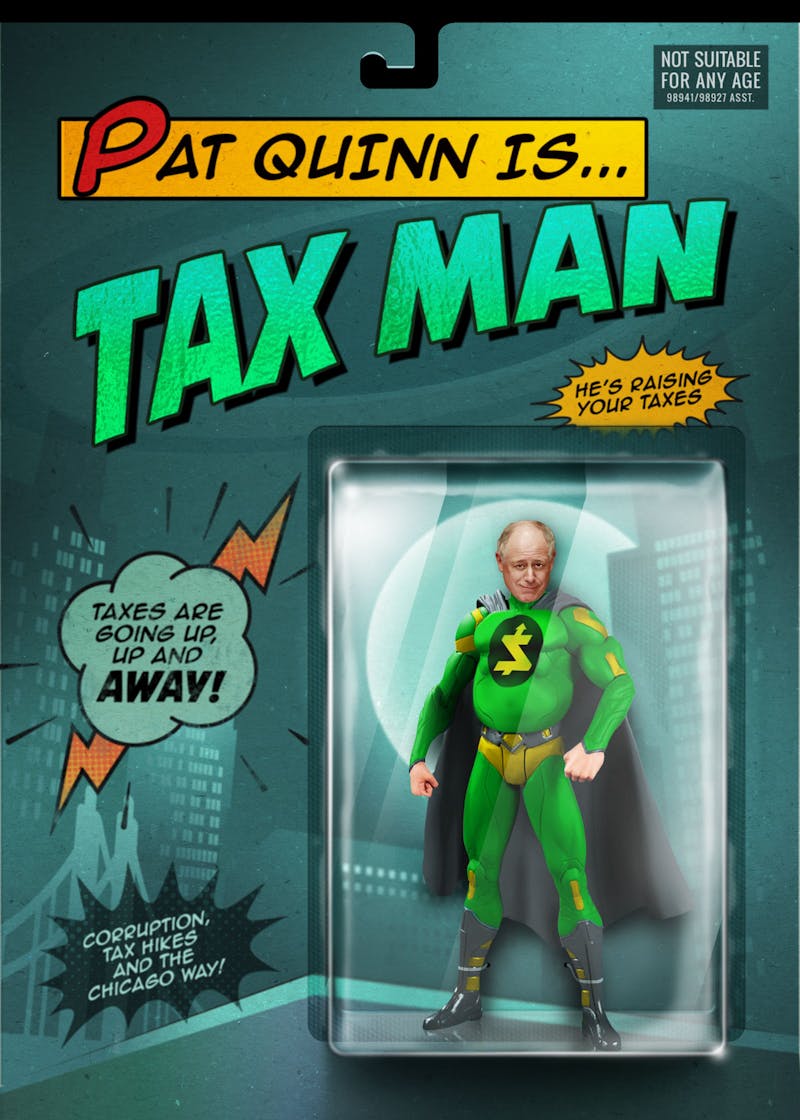

Candidate Command, Roe's direct-mail firm, produced this piece for the Illinois Republican Party attacking Democratic Governor Pat Quinn, who was ousted that year by Republican businessman Bruce Rauner (who was also a client of Roe’s.)

As a student at Northwest Missouri State in the early ’90s, Roe battled with his liberal professors—one of whom, he told me, vowed that hell would freeze over before Republicans took back the Missouri legislature. He wrote a column for the campus newspaper called “Where I Stand,” addressing his thoughts on politics and current events to the “silent majority.” While his first column praised President Bill Clinton as an “asset to the United States” who did “a fine job” passing NAFTA, he went on to blast the president for Whitewater, health care reform, and his three-strike policy on criminal offenders (as too lenient). He joined Tau Kappa Epsilon because TKE was Ronald Reagan’s fraternity, and he earned a degree of notoriety as an upperclassman for trying to steal another fraternity’s sign. (Roe pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and was put on probation.) During summers, he worked on a jackhammer crew for the Missouri Department of Transportation.

On a college trip to Jefferson City, the state capital, Roe met an up-and-coming state representative and conservative culture-warrior named Sam Graves from the state’s northwestern-most corner. The two country boys hit it off. Graves was running for state senate in a district he didn’t know well. The district included Roe’s hometown of Brookfield, and the lawmaker asked if Roe would work for him. When the time came to decide between reenlisting in the Army National Guard or plunging headlong into politics, Roe chose politics. On June 6, 1994, he finished his stint in the Guard; the next day, he began his first paid political gig working on Graves’s winning campaign.

Roe established himself as Graves’s right-hand man, running his state senate office and getting him reelected four years later. In 2000, Graves made a late entrance into the race for an open U.S. House seat previously held by a conservative Democrat. Republican officials had initially blessed another candidate, a city council member named Teresa Loar, but they quickly changed course and threw everything behind the better-connected Graves. The campaign—along with the one Roe ran two years later against Democratic challenger Cathy Rinehart—offered an early glimpse of the soon-to-be notorious tactics used by Roe and his underlings. According to Loar and Rinehart, camera-wielding Graves staffers repeatedly ambushed their campaign offices and tracked them at nearly every parade, fair, and public event they attended. Roe’s young team dug through their opponents’ trash; Rinehart told me she resorted to dumping dirty kitty litter in her garbage to ward off Roe’s Dumpster divers. Loar recalls young men she knew to be Graves staffers posing as journalists or volunteers in order to get inside her campaign and catch her saying something incriminating. “‘The little brown shirts,’ I called them,” Loar said. (Roe confirmed some of this, but couldn’t recall all the details.)

When Graves went to Washington, Roe was Graves’s chief of staff and political consigliere. In Washington, you can always spot a member of Congress by their lapel pins; Roe, a former staffer said, was like a “member without a pin.” But he wasn’t finished with Missouri. When Roe had gotten his start, Republican officeholders were a pretty rare breed in northwestern Missouri. But Roe and Graves successfully recruited and backed numerous Republican candidates for both local and state races. These efforts helped propel the red wave that saw Missouri Republicans take full control of state government in 2004 for the first time in more than 80 years. “In the western half of Missouri for sure, Jeff was an integral part of that,” said Lager, whom Roe recruited to run for state house.

In late 2005, Roe left D.C. to

parlay his successes into his own firm, Axiom Strategies. He started off small, with one other employee and an intern on the

second floor of what is now a bail bondsmen’s office in downtown Kansas City. At

first, he offered only strategy—his advice—and outsourced the rest. But it was a propitious time to open a consulting firm: Republicans were ascendant in

Missouri, and the state’s limits on

campaign giving and spending would soon be toppled altogether, unleashing a

torrent of money.

Roe hung war-themed art on the

walls, stocked the fridge with Diet Mountain Dew, and, former staffers say,

treated them at times like a family, at others like a platoon. He organized a

weekly Bible study and insisted on all-hands, family-style lunches in the

office. But Roe also dismissed employees for the day for arriving five minutes

late, and he expected timely responses to emails whether they came at 7 a.m. or

10 p.m. If the office phone rang more than twice, it went to Roe’s line. “On

the second ring, you’re jumping across desks to answer the phone so it doesn’t

ring a third time,” one former Axiom staffer told me. The whole experience,

said the ex-staffer, was like a fraternity hazing. “Ten years from now, you can

say to somebody else who went through it, ‘Damn, that sucked. But we got

through it.’”

One morning in the fall of 2006, Sara Jo Shettles, a Democratic nominee for Congress from just northeast of Kansas City, was out on a campaign trip with her adult son. From the other side of their motel room, Shettles’s son yelled for his mom to come look at what was on the TV. “I looked up and there I was: the worst possible picture of me in the world with a big ‘XXX’ over my head in bright letters,” she recently recalled. The 63-year-old, wheelchair-bound Shettles, a longtime Democratic activist, was running against Sam Graves—and, by extension, Jeff Roe. Shettles had neither the money nor the name recognition to mount a real challenge to the three-term incumbent. But that didn’t stop Roe.

Years before, Shettles had worked for General Media Inc., selling ads for the science magazine Omni and a few other trade mags. Roe seized on the fact that General Media’s flagship title was none other than Penthouse. That was more than enough for him to cut the defining ad of the race. His triple-X attack ad accused Shettles of peddling “smut” and effectively made her out to be a pornographer. Shettles defended herself by saying she was hired by Omni, paid by Omni, and never sold ads directly for Penthouse. (She told me recently that she handled contracts that also included ads for Penthouse.) Roe wasn’t buying it. “She worked for scum,” he told the Kansas City Star at the time.

Shettles had challenged Graves to a debate during the campaign. Not long after the triple-X ad aired, she returned to her campaign office to find a voice mail message from Roe:

[Roe hums a melody] Hi, this is Jeff Roe calling from Penthouse—I mean, uh, Graves for Congress. Call me when you can. I’m interested in your debate memo. I know you’re waiting on a sponsor for a media host. So, gimme a call when you get a chance. 407-NAUGHTY-GIRLS—I mean, 1222. Gimme a call when you can. Thanks. Bye.

I recently played back the audio of

his “naughty girls” voice mail to Roe. “Not my finest moment,” was all he said. The way Shettles sees it,

trashing her name and reputation was all a game to Roe. “He felt that was

absolutely 100 percent acceptable,” she told me. “And it was, in all reality,

an overkill.” Graves beat Shettles with 62 percent of the vote.

The more notorious Roe became, the

more extreme his tactics. The same year as the Shettles race, Roe injected

himself into a Republican primary 250 miles away in which he had no client. The

suburban St. Louis race pitted an incumbent state senator named Scott Rupp, who Roe preferred, against a more moderate county councilman named Joe Brazil. Roe had started

a blog called The Source (now defunct), where he posted political analysis,

gossip, and dirt he’d dug up on rival candidates, their staff, and their

families. “Candidates and children of candidates—their Facebook and MySpace

pages are the first thing we check,” he told a reporter.

On August 4, 2006, a few days before the primary election between Rupp and Brazil, Roe posted an item rehashing what Brazil later called “the most painful thing that ever happened in my life.” Decades earlier as a teenager, he’d been driving a dump truck in his high school parking lot as part of a class prank when he accidentally threw his best friend from the truck and drove over him, crushing him to death. Roe wrote that Brazil had had “quite a few beers” at the time of the accident (a police report filed afterward said the opposite—that Brazil hadn’t been drinking) and concluded the post by writing, “So now we have another instance of Brazil’s irresponsibility and not owning up to his mistakes. What else do we need to know Joe?” (Brazil was not charged in the incident.)

The post was “passed around like a dirty dishrag,” as a local GOP official put it. Brazil ended up losing the primary, but he never got over Roe’s smear. In 2007, Brazil sued Roe for defamation for the drinking claim. A judge ultimately dismissed the suit, but not before Roe admitted in a deposition that he’d never read the police report and had based his post—which he took down after Brazil sued him—on a reader-submitted entry in the Darwin Awards, a website that compiles stories about how people die in embarrassing and untimely ways.

I asked Roe about all these incidents, along with many more rumors I’d heard, over the course of our conversations. He said the Shettles Penthouse ad was accurate. He refused to comment on the Brazil episode. What came through most clearly was Roe’s lack of repentance. He sees no reason to apologize—quite the contrary, in fact. When a Kansas City Star column appeared in 2007, criticizing his tactics under the headline, “Voters Seem OK With Political Low,” he had the story made into a plaque for his wall at the Axiom office. “Politics ain’t beanbag,” he likes to say.

Roe’s most memorably brutal ad appeared in the 2008 cycle, a race that had the potential to make or break his fledging consulting business. After years of hedging, Kay Barnes, the former mayor of Kansas City, had announced she was running for Graves’s seat. Barnes, who had left the mayor’s office in good standing with voters, posed the most formidable challenge Graves had faced. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee listed Barnes as one of its top recruits, and Graves as a prime target, in what was predicted to be a Democratic wave year.

Roe felt his consulting future was on the line. “If you lose that race, what’s your narrative for going around the country telling people you know how to win a congressional race?” he told me. “It was a prove-it race without a doubt.” He hit Barnes early and hard. The Democrat had attended a fund-raiser in San Francisco hosted by Democratic House leader Nancy Pelosi, providing fuel for the spot Roe unleashed in the spring of 2008. Set against images of streetcars and a flamboyantly dressed black man dancing at a club with two women holding cocktails, the spot depicted Barnes as a far-out liberal with “San Francisco style values” who fund-raised with Pelosi and became a darling of “West Coast liberals by promoting their values, not ours.”

The attack—which reads now as a rough draft for Cruz’s recent “New York values” hit on Donald Trump—was blasted as homophobic and borderline racist. (Roe declined to comment on the ad.) But as Roe well knew, Graves’s district—which included only a small section of Kansas City—largely covered socially conservative northern Missouri, where ripping into “San Francisco values” would be catnip for the conservative base. Barnes’s campaign never recovered. (And she did not respond to requests for comment.) In what was supposed to be one of the most hotly contested House races in the country, Graves won with 60 percent of the vote. He has never faced another serious challenge since.

The view was incredible. The Kansas City skyline spread out before him, like a picture postcard. It was 2011, and Roe and his firm had recently moved into a new 3,300-square-foot headquarters on the city’s northern outskirts in a ritzy office park named Briarcliff. Axiom boasted an impressive 81 percent win record in congressional races, and Roe was becoming one of the most sought-after consultants in the country. His firm was now working on dozens of races each cycle, with millions of dollars in revenue coming in the door. Roe had recently opened a satellite office in Washington, D.C., and would soon open another in Dallas. His clients were spread across the country, and his office had clocks set to Los Angeles, Denver, Kansas City, and Washington time. Roe hung a blowup version of the famous aerial shot of Muhammad Ali’s 1966 knockout of Cleveland Williams. He displayed newspaper headlines for all the big races he’d won. On his desk, he kept a photo of his grandparents’ farm.

Jeff Roe the Bad Boy had become Jeff Roe the Businessman. The timing couldn’t have been better: Not only had Missouri’s Republican legislature all but deregulated the state’s political system, but in January 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court had handed down its Citizens United decision, paving the way for unlimited political spending by corporations and labor unions (and for the creation of super PACs). The radical overhaul of campaign finance was a huge gift to political consultants everywhere. It was time for Roe to put a bowl on his head, just as his grandfather had told him.

Roe grabbed those huge gobs of money with both hands, growing his little strategy shop into a consulting conglomerate operating in nearly every facet of twenty-first-century politics. He spun off his direct mail and polling operations into their own respective companies, Candidate Command and Remington Research, that pull in millions of dollars every election cycle. He started a spin-off firm solely devoted to franked mail, the glossy mailers and brochures sent out by members of Congress to their constituents, all paid for by taxpayer funds. Roe’s Capitol Franking Group, according to House spending records, takes in hundreds of thousands of dollars a year producing mailers for Graves and others.

As Axiom grew its portfolio, Roe took on a number of corporate clients as well. Among the most prominent was the behemoth defense contractor Lockheed Martin. (Other corporate clients have included tobacco giant Altria, AT&T, Microsoft, and Peabody Energy, the largest private coal company in the world.) In October 2011, with Roe working behind the scenes, Missouri State Representative Caleb Jones sponsored a resolution that called on Congress to boost funding for Lockheed’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, made in Texas. Problem was, the F-35’s main rival was Boeing’s F/A-18 Super Hornet, made in St. Louis. This was puzzling: Why would a legislator advocate for taking jobs away from his own state? (Jones, a Republican, declined to say at whose behest he offered the controversial resolution.)

Tony Messenger, an editorial page writer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, dug around and connected the resolution (which Jones apologized for after a public outcry) to Roe. “How do you connect it to me?” Roe replied, according to Messenger. “I don’t think you can do that.”

“Jeff,” Messenger said, “Lockheed’s your client.”

“Well, they may or may not be, but how would you know?”

“Jeff, it’s on your fucking web site.”

“Oh, okay.” Pause. “How’s the wife?”

Roe said he doesn’t recall the conversation. But Axiom’s web site no longer lists its corporate clients.

Axiom has also worked for candidates and causes that might make a Ted Cruz supporter balk. Federal election records show the National Republican Congressional Committee, an establishment party organ and bête noire to the far right, paid Roe’s firm nearly $90,000 between 2009 and 2014 for strategy consulting, among other things, according to federal election records. Roe helped mainstream Republican Senator Pat Roberts in Kansas—a RINO in the eyes of many conservatives—defeat a Tea Party challenger and win re-election in 2014. Perhaps most damaging in the eyes of movement conservatives, that same year Roe’s mail firm was behind a $234,000 negative ad blitz in Kansas’ 1st congressional district funded by a super PAC called Now or Never. The target was one of the most conservative members of Congress, Representative Tim Huelskamp of Kansas, who was being challenged in the Republican primary.

Roe’s role in attacking Huelskamp led to an awkward encounter in November, when Cruz and Roe met with a group of congressional Republicans to tout Cruz’s candidacy. As National Review reported, Representative Paul Gosar of Arizona, a member of the Tea Party-friendly Freedom Caucus, brought up Roe’s efforts to defeat Huelskamp and questioned whether Roe’s firm would attack Huelskamp again in 2016. Roe assured Gosar that he was working “100 percent” for Cruz’s presidential campaign, and that he would have no active role in his firm’s work for 2016. After the meeting, Roe released a statement praising Huelskamp for his “principled, conservative leadership.” (Huelskamp has yet to endorse Cruz, or anyone else.)

Closer to home, Roe took on lucrative jobs from corporations, tax referendums, and, occasionally, local Democrats. In Kansas City, municipal elections are technically non-partisan, but the candidates are predominantly Democratic, and Roe and his firm have worked for several of them in recent years. In 2011, Axiom advised Kansas City Mayor Mark Funkhouser, who, while boasting somewhat of a libertarian streak, allied himself with then–New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Mayors Against Illegal Guns group and sang the praises of the city’s labor unions. Separately, last year Roe’s firm worked for four Kansas City council candidates—including the former president of the local firefighters union. All four lost. (Roe declined to comment on his work for Democrats.)

Roe has run campaigns both supporting and opposing tax increases. One of the former was a successful effort in 2006 to increase local sales taxes by $425 million over 25 years to fund renovations at the Truman Sports Complex, home to Kansas City’s professional baseball and football teams. Another was a 2011 campaign to pass a multicounty sales tax hike to upgrade the Kansas City Zoo. That succeeded as well, generating between an estimated $14 million and $17 million a year. Even after those efforts, Roe was still viewed as a diehard conservative, and he shocked many observers of Kansas City politics in 2013 by joining forces with major corporations and the local Chamber of Commerce to support yet another sales-tax increase to fund advanced new medical research. Pete Levi, the former president of the Greater Kansas City Chamber, said Roe’s hiring came as a surprise to supporters of the measure. “Jeff, because of his opposition to a lot of measures, had a black-hat reputation in the community,” Levi said. “Jeff is very concerned about his reputation, and working on translational medicine ... was his chance to shine in the eyes of the business community.”

Despite early polling support for the measure and a four-to-one spending advantage, the medical research initiative went down to an embarrassing 63-point defeat. It wasn’t all bad news for Roe, though. He’d burnished his image with the local business crowd—Levi calls him “phenomenal”—and his various firms got paid $110,000 for a few months’ work.

Roe’s friends and former colleagues

say he’s always dreamed of running a presidential campaign. Really running it, that is: steering the ship, leading his team

through the crucible, fielding the candidate’s nervy emails at 1 a.m., maybe

writing a how-I-did-it book when it’s

over.

In 2007, Roe took a liking to Mike Huckabee, the folksy former Arkansas governor running a threadbare campaign for president—one that would offer plenty of opportunities for an ambitious consultant. Back then, Roe didn’t have much of a reputation outside of Missouri, so he more or less walked on to Huckabee’s campaign, showing up one day with bagels at the Des Moines office. He started making voter calls to prove his loyalty. “I wouldn’t let my wife come” in to the office, he said, “because it’s a kind of humbling deal.” A senior Huckabee aide soon figured out who Roe was. Can you get us some computers, she asked. Yeah. More phone lines? Sure. Robo-dials? Coming right up. Roe helped run Huckabee’s ground game and phone banks; after powering Huckabee to a win in Iowa, he turned to voter-targeting efforts in several more primary states.

After working on Rick Perry’s ill-fated 2012 presidential run, Roe cast an eye to 2016. He and his wife, Melissa, who was crowned Mrs. Missouri United States in 2010, went back and forth about which potential candidate would be best. This time, it wouldn’t just be about the money, it would be about the client. His wife told him, according to Roe, “If you really want to change the direction of the country, if you really want to spend this much time and energy and resources to do a presidential, you ought to do it for somebody you think will change the country if they win.” While on a cruise, the couple cut a deal: They’d independently jot down the name of their preferred candidate and then simultaneously reveal their choices. They scribbled, then flipped. Both chose Cruz.

After Cruz also chose Roe, he moved his family and in-laws to Houston as he’d promised—and he insisted everyone else on the Cruz campaign do the same. There would be no far-flung team members, no interminable conference calls. Everyone who wanted a spot on the campaign had to move to sweaty Houston. “This is a cause and not a client,” Roe said. Senior-most members of the campaign put their businesses on hold—like Chris Wilson, the CEO of Wilson Perkins Allen Opinion Research, who runs Cruz’s data and research team. According to a senior Cruz aide, Roe runs the office much the way he did Axiom. Meetings are conducted with brutal efficiency, punctuality matters, and Roe is quick to dispense parables from the hog farm and howitzer crew to make his point.

But his contribution has gone far beyond the tight running of the operation and the on-message consistency of the candidate. At the outset, Roe said, the most common perception of Cruz was as a “Texas Tea Party firebrand.” But to win, Cruz needed more than just Tea Partiers. He needed the whole base—which just so happened to be Roe’s passion. So the campaign team, led by Roe, set in motion a plan to relentlessly court not just Tea Partiers but Christian evangelicals, libertarians, pro-lifers, the whole panoply of the far right. They set the campaign’s tone by choosing Liberty University, founded by the iconic evangelical preacher Jerry Falwell, as the setting for Cruz’s campaign announcement in March 2015.

Cruz’s strategy—stroke the conservative id, coalesce the base, and trash the establishment—has worked wonders so far. But over the long haul, Republicans on the outside of the Cruz campaign say it’s risky, especially in light of poor turnout within the base in recent elections. “It narrows the path,” one GOP operative not affiliated with a campaign told me. “If you put in place the turnout machine to get those people out, you can win the nomination. But you have to run the perfect race.”

That’s where Roe comes in. His job is execution, keeping the campaign focused, tuning out the distractions, ensuring the candidate is in peak condition day in, day out. “Sleep. Perform. Sleep. Perform,” he likes to remind his candidates. Roe himself is hard to knock off course. “There can be grenades going off around you,” said a Missouri consultant who knows Roe, “and he’s saying, ‘Here is what we need to do. Don’t get distracted. This is our path.’” But now that Roe’s steady leadership of the campaign has vaulted Cruz into contention, the Texas senator finds himself in the crosshairs of national polling leader Donald Trump and Senator Marco Rubio, who’s running third. As the race grows more heated, Cruz will find it increasingly hard to refrain from punching back at his competitors. The question is whether—or when—he will unleash Roe’s brass-knuckle tactics.

Roe certainly hasn’t lost his edge. In February 2015, nearly a year after Cruz had hired him, he produced a radio ad attacking a Republican primary candidate for Missouri governor named Tom Schweich. Roe was an adviser and friend of Schweich’s main GOP rival, Catherine Hanaway. The radio ad—which aired only a handful of times in the lead-up to the GOP’s annual Lincoln Days celebration—mocked the physical appearance of Schweich, who suffered from Crohn’s disease which kept his weight around 140 pounds, comparing him to Barney Fife, the bumbling deputy on The Andy Griffith Show, and painting him as a weakling. If Schweich were nominated for governor, the spot vowed, Democrats would “squash him like the little bug that he is.”

Even before the ad aired, Schweich had been fighting a war inside his own head. He believed that the chairman of the Missouri Republican Party had spread false rumors that he was Jewish (Schweich was Episcopalian, though he had a Jewish grandfather). Schweich wanted to out the chair as a liar and a bigot, but his closest friends advised against it, leaving Schweich feeling personally and politically isolated. (John Hancock, the chairman, told me he may have mistakenly said Schweich was Jewish, but doesn’t specifically recall doing so.) A few days after the ad ran, Schweich fatally shot himself in the head. The spot had been formally sponsored by a group called Citizens for Fairness in Missouri, but after Schweich’s death, Roe told a local reporter he had produced and paid for it as a response to Schweich’s attacks on Hanaway.

Roe was vilified. In his eulogy for Schweich, who he’d mentored, former U.S. Senator John Danforth, a friend of Schweich’s and the closest thing to political royalty in Missouri, railed against Roe’s attacks without mentioning him by name. “Words do hurt,” Danforth said. “Words can kill.” Roe told me that Schweich’s death was “awful” and a “terrible situation.” He added, “My heart aches for his family, his close family, extended family.” But he expressed no regrets. “That’s not the way I live,” Roe said. “I live in the windshield, I don’t live in the rearview mirror.”

On the Cruz campaign, the first glimpse of Roe’s negative tactics surfaced in mid-January, when Cruz ripped Trump for his “New York values.” But while Roe’s infamous “San Francisco style values” attacks destroyed Kay Barnes in 2008, “New York values” did not go down so well. (Roe declined to comment on his role in “New York values.”)

From George W. Bush to Donald Trump, here’s everyone who can’t stand Ted Cruz.

It was an attack that could play well

in the heartland, but it drew immediate wrath in New York. “Drop Dead, Ted,” the New York’s Daily News declared on its cover, accompanying the headline with a

picture of the Statue of Liberty flipping the bird. The attack not only led to

uncomfortable questions from the media and at least one academic about the implied anti-Semitism of singling out New

York for scorn, it opened the door for a genuinely moving response from Trump,

at the January 14 Republican debate, about how New Yorkers responded to

September 11. In the aftermath, even Cruz’s own allies questioned his

campaign’s judgment. “It would have been better on the part of Ted Cruz not to

have had that exchange” with Trump, said Representative Steve King, a key Cruz

surrogate, on CNN.

However “New York values” plays out down the line, it certainly sounded like pure Jeff Roe. And the deeper into the race Cruz goes, the greater the need for Roe’s negative tactics may be. What might Roe have in store for Trump, Rubio, or Hillary Clinton? And will it help Cruz, or blow up in his face?

Roe has no illusions: He knows that either his headiest days, or his most difficult, might lie ahead of him in 2016. Still, few observers ever expected Cruz’s campaign to come as far as it already has. Anything short of a complete meltdown, or a debilitating scandal, will seal Roe’s status as the face of a new crop of political Svengalis. In that sense, you could say that Jeff Roe has already won.

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.