Fashion photography, so often criticized for requiring models to pose in extreme physical contortions, or dress up as suicide victims, or in blackface, has had some excellent press of late. A September 2014 piece in The New York Times declared that “fashion photography is art’s rising star.” In the last year there have been exhibits on fashion photography around the world: at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and an exhibit called Vogue: Like a Painting at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. The exhibit’s accompanying catalog, out this month, presents 67 fashion photographs that are directly influenced by well-known paintings. Their relation to fine art, it is implied, makes the photographs worthy of consideration primarily as art works, rather than representations of the status of women, or advertisements for once-novel styles of dress.

Leafing through Vogue: Like a Painting can be a fun game of connections for the art enthusiast: here is the photo inspired by Gauguin, here is the one that seems to reference Andrew Wyeth. A Peter Lindbergh shot from 2012 recalls Velazquez’s Las Meninas; Patrick Demarchelier (2011) draws inspiration from the Impressionists for his scene of a woman and child at the seaside; Glen Luchford (1995) and Camilla Akrans (2010) both posed models next to windows, like Edward Hopper’s Hotel Window or Morning in a City. But the photographs don’t reproduce the social, political, and cultural commentary that made those original paintings so powerful. A photo by Paolo Reversi is reminiscent of John Singer Sargent’s Madame X, but the model’s skin and defiant stare is less controversial—less convention-breaking—in 2005 than 1884.

Moreover, the emphases of the images are sometimes eccentric. The eye is drawn to the visual elements that connect the photo to the original painting, rather than to the subject of the piece itself. For his 2012 photograph, Peter Lindbergh posed four women in dancing in a circle around a tree, hands linked, looking away from one another in a construction that resembles Nicolas Poussin’s A Dance to the Music of Time and Matisse’s The Dance. The models’ faces are all twisted away from the camera, leaving only the suggestion of motion in their bodies and emphasizing the froth of cloth and embroidery that surrounds them. The dresses’ silhouettes resemble Degas’s Ballet Dancers in the Wings, connecting the past to the present in a lineage of cloth. Their connections to these paintings elevates the photographic images to the realm of the untouchable. The dresses, though gorgeous, seem unlikely to ever be worn outside the frame—unattainable and therefore, the advertising logic goes, incredibly desirable.

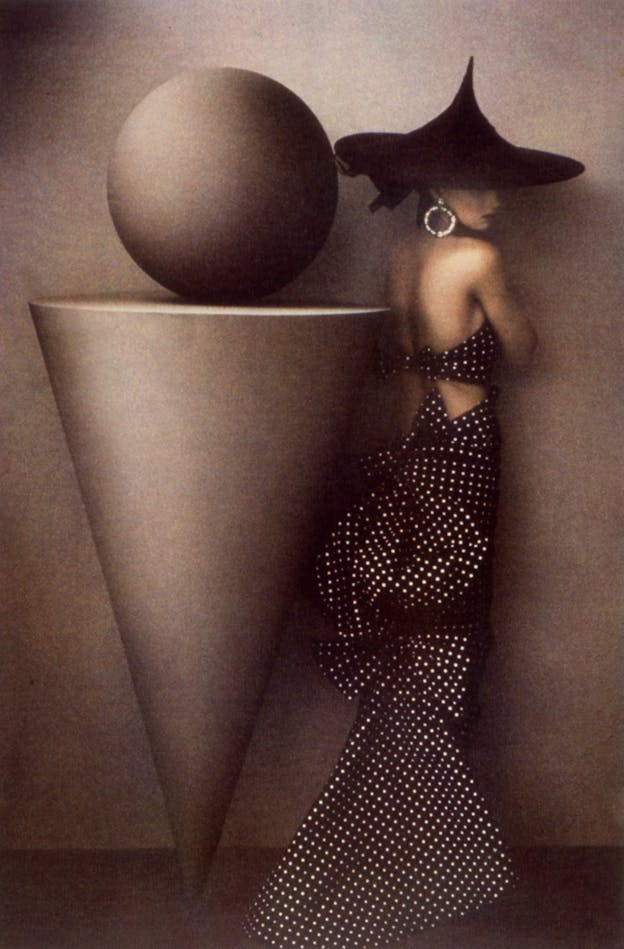

Lucy Davies, an art and photography critic for The Telegraph, claims in her introduction to the catalogue that the photographs “revere rather than objectify women.” There are no gratuitously sexual images, and the occasional nipple is so powdered that bare torsos resemble Roman statuary. But although there are photos that feature women looking daringly straight at the camera (two versions of Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring), most of the models’ faces are obscured by hats, hair, ruffles, or simply positioning. Works of art that featured round and dimply bodies arrayed in silks are now flattened and bleached, so that the female figures in them seem even less alive than when they were painted in oils. In some, the paintings’ female subjects have completely disappeared: Tim Walker’s 2004 photo of neon dresses floating in a tree resembles the paper lanterns of Sargent’s Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, but the girls in the original painting are gone. The empty dresses emit a glowing light, unfilled vessels that invite anyone to try them on. These photographs don’t objectify or revere women: they revere light, shadow, and fabric.

The best shots in the exhibit are those that emphasize the unreality of the fashion world, in which the clothes are exaggerated. A fanned-out dress in a 1992 shot by Nick Knight transforms the model into a swan, and an elaborately tiered garment in a Knight image from 2008 turns the model into a tower of pure magenta, like the stamen in a Georgia O’Keeffe flower painting. The unimportance of the models is disturbing but hints at a refreshing truth: here is an honest admission that the fashion world is fundamentally unconcerned with human women.

That does not make the abundance of dead and deeply unhappy women in these photographs (or women playing dead) less shocking. The art world has always loved a beautiful dead woman, and fashion is no different. (Mallory Ortberg’s series at The Toast subverts the pleasure we take in these images, by giving them deflationary captions, suggesting what the female models are really thinking. It’s difficult to take seriously Lindberg’s photograph of dancing girls after reading her post on “Women Dancing Miserably In Western Art.”) There are two images in the exhibit inspired by John Everett Millais’s Ophelia, both featuring alabaster-skinned women swathed in ivory silk, floating amongst verdant ferns and lilies; undeniably visually appealing in an art catalog, but of questionable message in the pages of a magazine. Vogue presents an aspirational dream and impacts the physical ideals of women around the globe. Those ideals, which run through the collection, are mostly thin, mostly white, mostly morbid.

One of the most arresting shots, by Peter Lindbergh, features a woman undressing. The grey-scale coloring renders the tone of her body and fabric the same; she seems to be almost taking off her own skin, shedding the layers that constrain the women in other pieces while signaling a deeper discomfort with self. Vogue: Like a Painting is meant as a celebration of Vogue’s legacy of fashion photography at a time when the magazine is facing criticism for diversity problems and body image issues; accordingly, the collection consciously displays high fashion as fantasy, not to be tethered by real-world issues. But the photographs of Lindbergh, Knight, Akrans and others make clear that it’s a fantasy some women, inside the photographs and out, are keen to escape.