"I'd like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company. That's the real thing."

“The reason you haven't felt [love] is because it doesn't exist,” Don Draper told Rachel Mencken in the show’s first episode, back in 1960 by way of 2007. “What you call love was invented by guys like me, to sell nylons.” It was one of “Mad Men”’s first memorable lines, but like so much of the Don Draper persona, it was a bluff. For a show about one of the major engines of twentieth-century American commerce, “Mad Men” has never been that outright cynical. Love exists—Stan loves Peggy; Joan loves her son; even after everything he’s done, Sally still loves her father. Guys like Don Draper didn’t invent love; they just made good use of it.

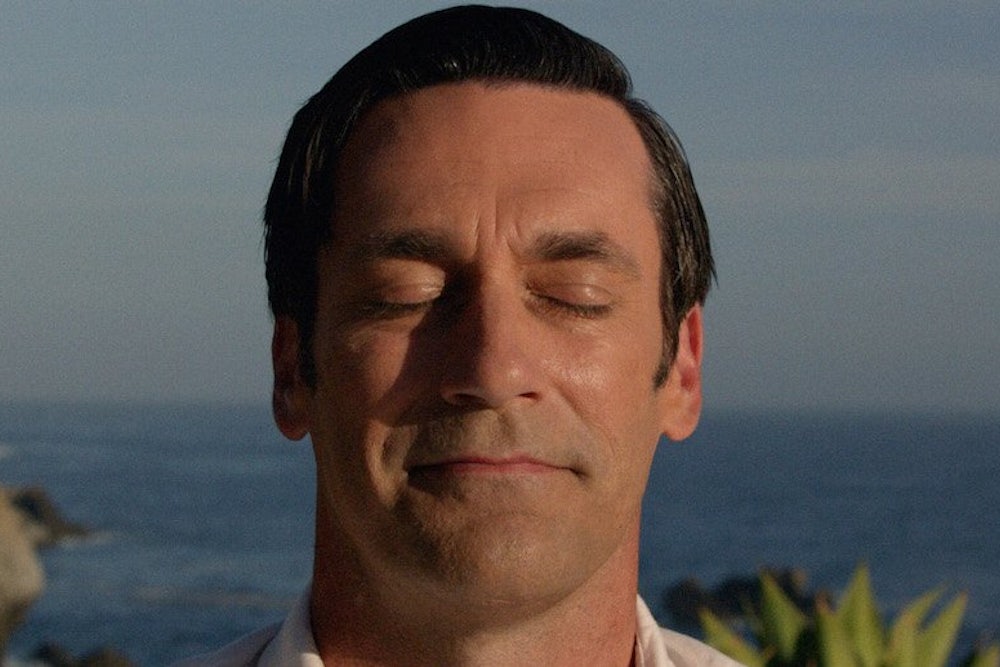

That line from the pilot was what I kept coming back to after the final moments of “Mad Men” last night: Don sitting cross-legged on a verdant cliff, chanting “Om” and smiling before suddenly, and ironically, giving way to the wholesome gongs of “I’d Like to Buy The World a Coke.”

So was what we call peace and enlightenment invented by guys like Donald Draper to sell Coca-Cola? That smile on Don’s face—was that the smile of a man who’s found a sort of inner peace at California’s Esalen Institute, or a man who just had a killer idea for a commercial? Did Don stay in Big Sur for a while, meditating and hugging his way through the ’70s, or did he return to New York in time to create that iconic Coke commercial in 1971? Matthew Weiner left some ambiguity, but not fades-to-black-is-Tony-dead ambiguity.

In the last few weeks, a number of critics have guessed this ending: that Don Draper would be responsible for “Hilltop,” the ad created by McCann-Erickson in 1971 for Coca-Cola. Perhaps the strangest thing about this finale was that Matthew Weiner—who prides himself on confounding expectations, who warned us all not to expect closure, who told The New York Times last week, “I don’t really feel like I owe anybody anything”—gave us an ending that mapped so directly onto anyone’s predictions.

But that predictability was in keeping with the rest of the episode, which was filled with scenes that felt like fan fiction. Stan and Peggy declare their love and passionately embrace. Joan asks Peggy to be her business partner. Roger and Joan gaze proudly at their son. Pete and Peggy say goodbye, in a scene weighted with all their history. (When he tells her that one day people will brag about having once worked with her, she replies, “A thing like that”—a trademark Pete Campbell-ism, a phrase he used in the first season when she told him Belle Jolie liked her ideas.) These moments were satisfying, but almost too satisfying. “I think about how you came into my life and how you drove me crazy, and now I don’t even know what to do with myself because all I want to do is be with you.” Did we really want “Mad Men” to turn into Nora Ephron–lite? There was even a Charles Manson joke, a tiny nod to all those Megan truthers.

“Yes, everything, even our personal moments of clarity, can be co-opted by industry and turned for profit,” was the takeaway in Daily Beast’s review. And that’s true enough. Like nostalgia, self-actualization can be a servant of capitalism, ginned up to sell slide projectors and burgers and chocolate bars. But “Mad Men” has a more complicated relationship with commerce than that. In the real world, “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” was the brainchild of McCann-Erickson’s Bill Backer, along with former Motown songwriter Billy Davis: “So that was the basic idea,” Backer explained in his memoir decades later. “To see Coke not as it was originally designed to be—a liquid refresher—but as a tiny bit of commonality between all peoples, a universally liked formula that would help to keep them company for a few minutes.”

In "Mad Men," advertising—like the movies, like television, like the rest of twentieth-century mass culture—can make us feel a little less alone, for at least little while. Remember Don’s—and the show’s—most famous ad campaign: the Kodak carousel pitch that moved Harry Crane (Harry Crane!) to tears. “Happiness,” Don said, “is a billboard on the side of a road that screams with reassurance that whatever you're doing is OK. You are OK.” In May 1970, five months before Don arrived at Esalen, The New Yorker called the hippie retreat “a West Coast organization that seeks to connect people who feel disconnected from themselves and other people.” I’m OK, you’re OK. Don Draper found some connection while listening to another lonely man's sad story, and then he found a way of bottling up that feeling and beaming it in color onto the screens of millions of people. Is it the real thing? It’s something.