“Mad Men” begins airing the second half of its final season in April, and chances are you are due to be disappointed. Maybe Don Draper will topple out the window of a Manhattan skyscraper like the shadowy figure in the show’s opening credits, or maybe he will perish by more prosaic means. Maybe he will earn redemption, or maybe he will turn out to be notorious skyjacker D.B. Cooper. (Yes, that’s an actual theory circulating online.) Maybe the final scene will flash-forward through the rest of the twentieth century; maybe the screen will just fade to black. But the safest prediction about the finale is that it will make people very angry. Expect furious debates asking whether the show rewarded loyal viewers’ 80-something hour investment, or whether it wantonly betrayed their trust. It’s an outcome “Mad Men” showrunner Matthew Weiner has tried, futilely, to forestall. While the series began in 2007 with the intrigue of hidden pasts and switched identities, it’s never been propelled by a central question or mystery. When asked what viewers should expect from “Mad Men”’s end, Weiner has warned that the show will close on an ambiguous note: “My god, people must be prepared for that,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross in 2013.

If anything, the serialized television that has risen to the top of the cultural firmament in the last 15 years has prepared us for the opposite. The contemporary cult of the showrunner comes with its drawbacks, and one of them is the obligation to provide satisfying closure. “The Sopranos,” “The Wire,” “Breaking Bad,” “Game of Thrones”—these shows are densely plotted and narratively complex. Each episode is a link in a chain, filling in the puzzle but leaving the final picture unclear, and practically obliging us to tune into the next one. We sit riveted, lest we miss a clue. We wait for the big reveals—unless the whole season is available via streaming, in which case we binge, to hasten the payoff. We do not merely watch. We watch for the answers.

There are certain adjectives that the marketing people reach for when a big new show debuts. These series are bold. They are unconventional. But in fact, as a number of critics in recent years have noted (The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, Huffington Post’s Maureen Ryan, and Slate’s Willa Paskin among them), a formula has congealed, and it’s one with a particular flavor. The protagonists are macho and morally compromised. These men (of course they’re men) are brilliant at their jobs, whether that’s cooking meth or selling ads. The signifiers of Important Television have become so rote that copycat series like Showtime’s “Ray Donovan” and AMC’s “Low Winter Sun” have cynically adopted the genre’s gritty trappings without any of the intelligence or ambition of their forebears. Strip away the recycled ingredients, though, and the thing that links every prestige release is that it takes the form of an ongoing narrative. These shows are—to borrow a fetishized term from another medium—longform.

But that’s very recent history. The most celebrated shows of television’s early years only offered standalone episodes. These 1950s dramas—“Kraft Television Theatre,” “The Philco Television Playhouse,” “Studio One,” and the iconic “Alfred Hitchcock Presents”—were the new technology’s most respectable offerings, culling the talent pool of the New York theater world to offer up inventive and often thought- provoking self-contained stories. (In the first half of the decade, before the perfection of videotape technology allowed production to move to Hollywood, the episodes were performed live.) The shows were popular among the kinds of middle-class households that could afford a television set, but also felt sort of guilty about tuning into low-brow entertainment such as “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “Dragnet.” Playwright Paddy Chayefsky wrote intimate, slice-of-life teleplays for “Television Playhouse” that he then turned into feature films. Gore Vidal wrote a “Goodyear Television Playhouse” episode about an alien visiting Earth. But by the mid-’60s, the format had been entirely supplanted by series with continuing characters. Intermittent attempts at revival failed. In 1985, Steven Spielberg created a sci-fi/horror anthology series for NBC and got Martin Scorsese, Clint Eastwood, and Robert Zemeckis to direct. It bombed and was canceled after just two seasons.

For the next two decades, most television dramas stuck with the episodic approach, following a more or less consistent cast of characters but efficiently resolving conflicts within the hour. The first big departure from that format came with the premiere of “Hill Street Blues” in 1981. Created by producer Steven Bochco, the cop show was the anti-“Columbo,” with threads of storylines connecting each installment. Other shows adopted the style within different settings: a hospital, a law firm, a group of married yuppies. By 1995, amid the rapture over “ER” and “NYPD Blue” (another Bochco hit), Charles McGrath was heralding the rise of the “primetime novel” in a New York Times Magazine cover story.

That equation—TV as the new novel—became a stock phrase. But it was never quite accurate. Novels, even War and Peace–style doorstoppers, require only so much time to consume, and they always (obviously) have a definite ending, over which their authors have clear creative control. TV shows, by contrast, unfold over durations determined partly by business considerations. Consequently, the serialized TV dramas of the ’80s and ’90s tended to peter out, canceled mid-storyline (“Twin Peaks,” ending with Kyle MacLachlan’s Agent Cooper possessed by an evil spirit), or they were kept on the air by network executives who were happy as long as ratings stayed sufficiently healthy (“ER,” plugging along on life support for years after all its original characters had left). Finales were major events, but there was little expectation they provide any meaningful sort of closure. “St. Elsewhere” used its last episode to suggest that the prior six seasons had all taken place in the imagination of an autistic boy with a snow globe. One critic called it “suitably daft.”

Then came “The Sopranos” and “The Wire” and, on network TV, “Lost.” As chronicled in popular histories like Alan Sepinwall’s The Revolution Was Televised and Brett Martin’s Difficult Men, these shows were presided over by small-screen auteurs who spun plots that could take years to be resolved. You could not haphazardly skip episodes. You could not watch while folding laundry. This new breed of series required commitment, to produce and to consume. These shows asked us to pay attention and (we hoped) would reward that effort. They taught us that everything we saw mattered, and so we hoped everything did matter, that everything would eventually add up.

Of course, crafting a perfect conclusion to any long, intricate story is extraordinarily difficult. While soap operas cleverly slip the trap by simply never ending, primetime dramas have no such luxury, and so their writers must hurl themselves at the challenge head on.

“Lost” creators Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse seemed to score a breakthrough when the showrunners negotiated a firm end date to their series in advance. In 2007, the duo announced to the show’s obsessive fans that “Lost” had exactly three seasons left. The deal, however, turned out to be a mixed blessing at best. Lindelof and Cuse could block out their remaining episodes without having to worry that “Lost” would be canceled abruptly or dragged out for another decade. But the decision also implied a grand plan for the show’s central story, a deliberately constructed arc whose ending would shed light on everything that came before. When “Lost” aired its two-and-a-half hour finale—involving a magical whirlpool and an afterlife where the whole gang passes into heaven inside what appears to be a Unitarian church—loyal viewers felt betrayed, angry that the show had left so many questions unanswered and wasted their time. The finale not only retroactively tainted all the episodes that came before it. It also empowered future TV viewers to call foul at any long-running show that they believe failed to stick the landing.

The most popular narrative TV form of the last couple of years grew out of an attempt to avoid those yowls of disappointment. “True Detective,” “Fargo,” and Ryan Murphy’s trailblazing “American Horror Story” provide a story that reboots each season, which, at least in theory, should lower viewers’ investments to less mania-inducing levels and reduce the creative degree of difficulty at the same time. (Another more practical reason that the format has come into vogue: It’s easier to sign on a Matthew McConaughey or a Billy Bob Thornton when they only need to commit to one season.) “A lot of my frustration with serialized storytelling is a lot of shows don’t have a third act. They have an endless second act, and then they find out it’s their last year,” Nic Pizzolatto told an interviewer last year, explaining why he was doing something different with “True Detective.” “I wanted to tell something with a complete story, with a beginning, a middle, and an end.” But ironically, these hybrids put even more expectation on a tidy ending. And when a show breaks that contract, it can be even more infuriating—a prime example being the mystical scene at the end of the first season of “True Detective,” in which McConaughey and Woody Harrelson sit in a hospital parking lot, contemplating the battle of “light versus dark.” (So it went with the podcast “Serial,” which borrowed both its set up—“our hope is that it’ll play like a great HBO or Netflix series,”—and the inevitable fan letdown from the new breed of TV dramas.)

While the serial-miniseries mashups tease followers with a payoff that never comes, the recent British import “Black Mirror” has found a way to let itself off the hook. As a modern-day “Twilight Zone,” the sophisticated sci-fi drama harks directly back to the anthologies of television’s first golden age, deviating from the serialized blueprint of almost any other so-called quality drama of the last two decades. Equal parts melancholy and macabre, every episode of “Black Mirror” consists of a standalone story that begins and ends within the hour, linked to the rest of the season only by a shared aesthetic and point-of-view. The show drops us into an uncanny, near-future world to follow a premise to its often surprising end. In a second-season episode, a grieving widow subscribes to software that uses old emails, social media updates, and online photos to produce an idealized version of her dead husband. She is overjoyed to have him back—until she comes to see the doppelgänger as a sub-human half-servant, half-spouse, and winds up stowing him in the attic.

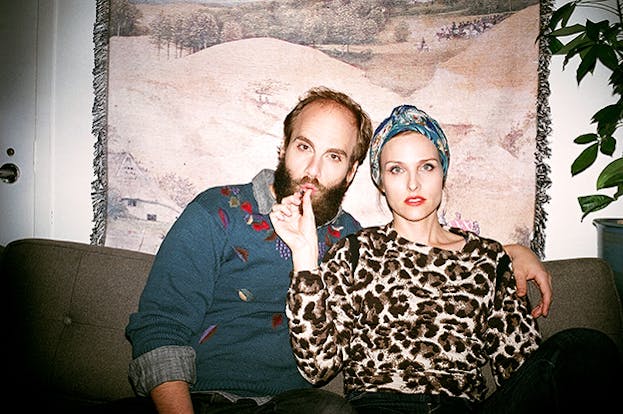

Then there is “High Maintenance,” the gold standard for Web series, currently in what the show calls its fifth “cycle” on the online-video platform Vimeo. Created on a shoestring budget by husband-and-wife Ben Sinclair and Katja Blichfeld, the show has only one regular character, if you can call him that: a gangly, bearded weed deliveryman. “The guy” is played by Sinclair and has no name; he’s merely a device. Each episode is about one of his customers, a constellation of lonely, needy, neurotic New Yorkers. There’s a couple driven crazy by their Airbnb guests, a comedian with PTSD, an asexual magician in his first year as a public-school teacher. (A few customers recur in multiple episodes, but only in the background.) Some installments take place in real time; others span months. Some are uproariously funny and some have a wistful irony to them. Some end with a punchline, but none result in what would be considered a traditional resolution. Watch a few of the six- to 18-minute installments, and you realize that you won’t get to find out what happens to these people when your brief time with them concludes. And so you stop asking. Without the suggestion of a dramatic pay off, the real drama lives in the ellipses. A pleasant ambiguity is built into the experience.

Most shows are best enjoyed the same way. An episode of “Mad Men” isn’t one more chapter toward an eventual conclusion; it’s an hour-long exploration of a theme, using the memories viewers have accumulated to produce a more potent response. Years later, “Lost” may not recommend itself as an intricately plotted mystery, but it holds up well if watched as a collection of character studies and pulp thrills. The emotional punch of its best episodes are still there: long-lost lovers, rekindled marriages, a paralyzed man stepping out of a wheelchair for the first time.

The water-cooler series of this golden age of television have taught us to look forward to that one final, stirring scene—but those final scenes were never really the point. The single-serving show might coax us into being better viewers, paying more attention to a show’s texture than to trying to predict its conclusion. They remind us of the folly of letting the pleasure of anticipation get in the way of the pleasure of what’s onscreen right now.