What was the biggest scandal in TNR history? Was it the 1994 publication of Charles Murray’s and Richard Herrnstein’s “Race, Genes and I.Q.,” an excerpt from their infamous book The Bell Curve? Was it Stephen Glass’s mind-boggling plagiarism that began the following year? Or was it the magazine’s support for George W. Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq? (Yeah, it was a rough 10 years for this magazine.)

There’s no right answer, but only one of those scandals was considered spectacular enough to warrant a Hollywood movie—and a good one at that. For three years, the young Glass charmed and hoodwinked his co-workers as he delivered one dazzling, too-good-to-check story after another. It all came crashing down thanks to a Forbes exposé, and Glass left journalism for good and set about reinventing himself as a lawyer. So it was dramatic, to say the least, when TNR in 2014 sent former staff writer Hanna Rosin, who had been Glass’s best friend at the time of the scandal, to confront him—and he agreed to talk at length about the incalculable damage he did to this magazine and his own professional life.

—Ryan Kearney, executive editor, The New Republic

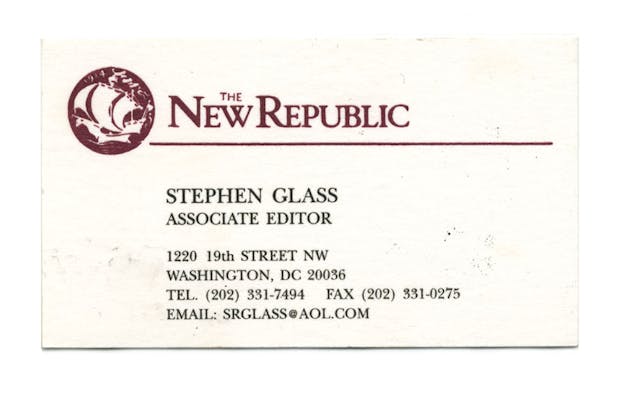

The last time I talked to Stephen Glass, he was pleading with me on the phone to protect him from Charles Lane. Chuck, as we called him, was the editor of The New Republic and Steve was my colleague and very good friend, maybe something like a little brother, though we are only two years apart in age. Steve had a way of inspiring loyalty, not jealousy, in his fellow young writers, which was remarkable given how spectacularly successful he’d been in such a short time. While the rest of us were still scratching our way out of the intern pit, he was becoming a franchise, turning out bizarre and amazing stories week after week for The New Republic, Harper’s, and Rolling Stone—each one a home run.

I didn’t know when he called me that he’d made up nearly all of the bizarre and amazing stories, that he was the perpetrator of probably the most elaborate fraud in journalistic history, that he would soon become famous on a whole new scale. I didn’t even know he had a dark side. It was the spring of 1998 and he was still just my hapless friend Steve, who padded into my office ten times a day in white socks and was more interested in alphabetizing beer than drinking it. When he called, I was in New York and I said I would come back to D.C. right away. I probably said something about Chuck like: “Fuck him. He can’t fire you. He can’t possibly think you would do that.”

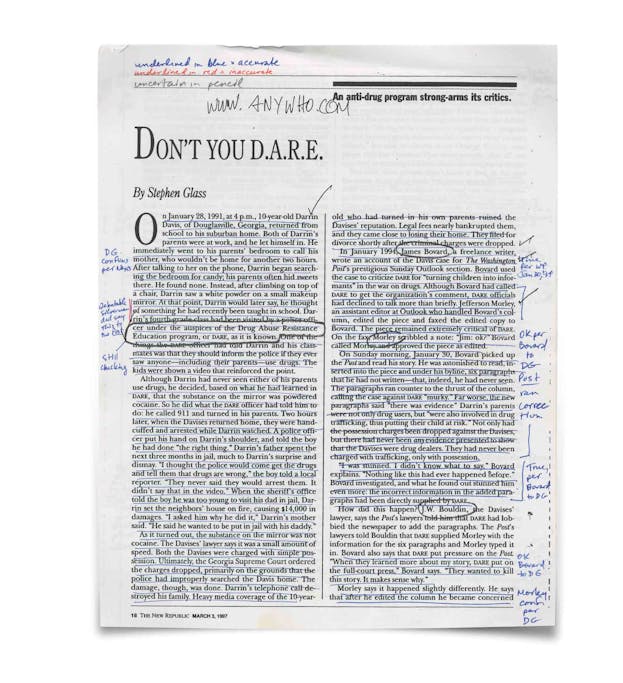

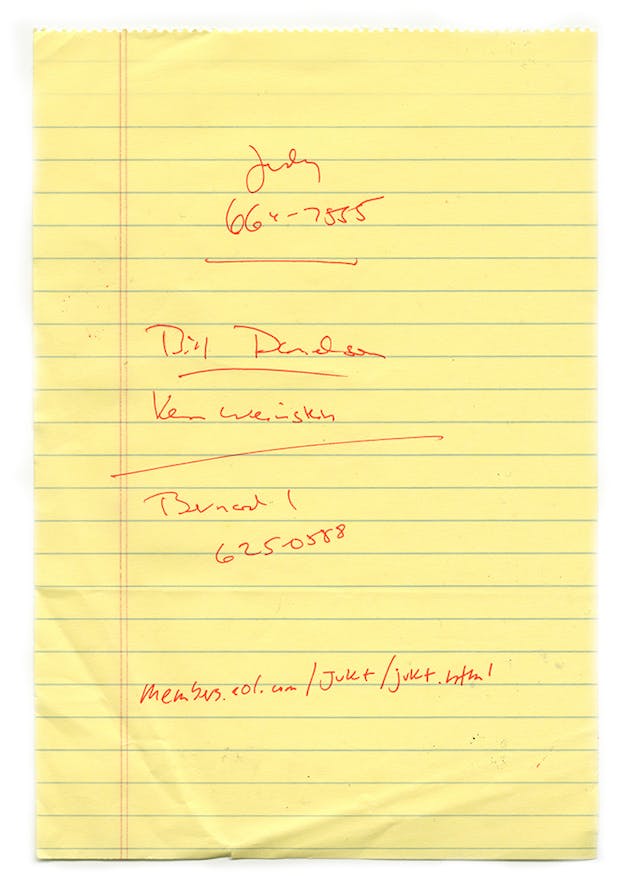

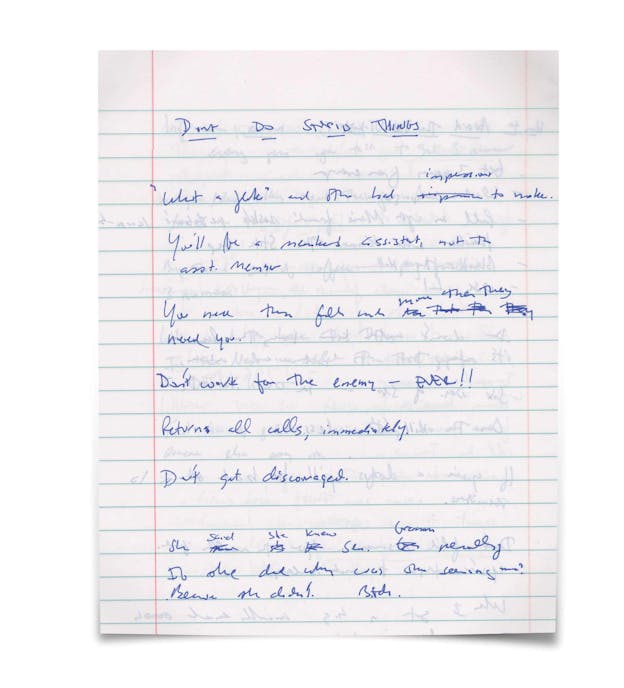

I was wrong, and Chuck, ever-resistant to Steve’s charms, was as right as he’d been in his life. The story was front-page news all over the world. The staff (me included) spent several weeks re-reporting all of Steve’s articles. It turned out that Steve had been making up characters, scenes, events, whole stories from first word to last. He made up some funny stuff—a convention of Monica Lewinsky memorabilia—and also some really awful stuff: racist cab drivers, sexist Republicans, desperate poor people calling in to a psychic hotline, career-damaging quotes about politicians. In fact, we eventually figured out that very few of his stories were completely true. Not only that, but he went to extreme lengths to hide his fabrications, filling notebooks with fake interview notes and creating fake business cards and fake voicemails. (Remember, this was before most people used Google. Plus, Steve had been the head of The New Republic’s fact-checking department.)

The Collection of The New Republic

Then, after a while, the dreams stopped. The Monica Lewinsky scandal petered out, George W. Bush became president, we all got cell phones, laptops, spouses, children. Over the years, Steve Glass got mixed up in our minds with the fictionalized Stephen Glass from his own 2003 roman à clef, The Fabulist, or Steve Glass as played by Hayden Christensen in the 2003 movie Shattered Glass. It was the book that finally provoked my anger. The plot follows a thinly fictionalized Steve in the aftermath of the affair. It portrays him as humble, contrite, and “a few shades hipper than the original,” I wrote in a review for Slate. The rest of us came off as shallow jerks barely worth apologizing to. Steve sent about 100 handwritten letters of apology that year to people he’d injured, all several pages long and very abject: “I’m genuinely sorry that I lied to you and betrayed you.” But he was also hawking his book, so we saw the letters as an effort to neutralize us. Reading the novel pretty much killed off my curiosity. For years afterward, if I thought about Steve at all—usually when I got an e-mail from a journalism student who had seen the movie in an ethics class—he was the notorious Stephen Glass, still living in the Clinton era.

Then, in 2010, I got a call from a lawyer in California. Steve had filed an application for something called “moral character determination” with the California state bar. He wanted to be a lawyer and the guild apparently did not think he had reformed enough to practice law. Did I want to provide an account of Steve’s wrongdoing? the lawyer asked. Chuck Lane was going to, and Steve had lined up several witnesses to speak in his favor. I said I would think about it and I did. For a few days, I tried to call up the anger again. But after all those years I could only find faint traces of it.

In fact, the prospect of appearing in court revived some of the old protective instincts. I hadn’t seen Steve in twelve years. I couldn’t say he deserved to be a lawyer, but I couldn’t say he definitively didn’t, either. (Since when did lawyers become the measure of purity anyway?) At stake for the lawyers was the sanctity of their guild. But for me, a larger question loomed: Agreeing that Steve could never practice law felt a little too close to agreeing that no one who had done something wrong—even monstrously wrong—in their youth could ever move beyond it. “I don’t wish him ill,” I’d written in my review of The Fabulist. “But I’m not convinced he’s changed all that much.” When the lawyer reminded me that the real Stephen Glass lived on the other coast, that he had professional aspirations, that he had friends who would stick up for him in court, that, in short, he was still making his way through time, it suddenly occurred to me: How could I possibly know if he’d changed or if he hadn’t?

Steve Glass now lives in Venice Beach with his longtime girlfriend, Julie Hilden, a dog, two cats, and a rotating cast of foster pets. (The couple are also vegans.) He works as director of special projects at Carpenter, Zuckerman, Rowley, a personal-injury law firm in Beverly Hills. For anyone who knew him back in the day, this is a comical juxtaposition. Steve is a Jewish boy from the posh Chicago suburb of Highland Park with pushy Jewish parents who insisted on the usual (doctor, lawyer). When they urged him to go to law school, they probably had Supreme Court appearances in mind, not, as the firm boasts, a $2.1 million settlement for a homeless man hit by a garbage truck. But Paul Zuckerman, the partner who hired Steve and has become his mentor, considers this development to be a sign of grace. “You were on track to be an asshole,” he told Steve when I was there. “The best thing that ever happened to you in your life is that you fell flat on your face.”

I’d e-mailed Steve this summer to see if he would talk to me. The New Republic was approaching its one-hundredth anniversary and the magazine wanted to revisit this dark chapter in its history. Other than publicizing his book, Steve hadn’t done any interviews since then, and certainly not with people from that era. But he readily agreed to talk to me, for reasons that became clear to me during the course of our conversations.

We decided to meet at a café near his office, and I ran into him on the street when we were both heading over. We said hello, reflexively hugged. I flashed back to the many times I’d run into him on the corner outside CF Folks, a lunch place near the old New Republic office in D.C. It was like encountering a cousin I hadn’t seen in some time. He had the same sandy curls and glasses, the same bouncy walk, and the pallor of someone who spends all day in an office. He still had the air of a nice boy who was about to theatrically help his grandma cross the street. Only something was a little different. He was more grounded? Or maybe masculine? For some reason it popped into my head that Steve had once wanted to write a story about how everyone thought he was gay but he wasn’t. He was floaty back then, undetermined, as if he could levitate in those white socks. But now he had lost that quality.

The first question he asked was whether I had any kids, which gave me a good idea of how far he’d strayed from his old world of journalist friends. (I have three, according to Wikipedia, and the many articles I’ve written mentioning them). I asked if he’d kept in touch with anyone from back then, and he said he hadn’t been able to. In the early days after the scandal, Steve told me, when he would see one of us on the street in D.C., he would become terrified, to the point of feeling “physically ill, like my stomach was falling out of me,” and turn and run in the other direction. He didn’t read any news about himself for a long time—it took him a year to read the Vanity Fair story about the scandal—because it was “extremely painful,” he said. Eventually that meant he fell out of the habit of reading much news at all, outside The New York Times and legal papers for work. I realized that for Steve, we too were frozen in the Clinton era. “It’s not realistic,” he explained, “but after a period of time, I was still convinced my old world of friends were having conversations amongst themselves, ... that you and Jon were still hanging out every day and I didn’t know what was going on. I didn’t get over the idea that it was one big club and I was no longer a part of it.”

On the plane to California, I’d imagined myself in the same role as the lawyer who’d asked me to appear at the bar hearing. I was going into intellectual combat, and I had to be well prepared. I dressed in an overly formal way, and I read Crime and Punishment on the plane to acquaint myself with the tricks of a guilty mind. I was wary of getting played again, and so I decided I would not spare Steve any question, no matter how uncomfortable. That phone call when he asked me to defend him to Chuck, for example. What was he thinking? “I was clearly putting you at risk to back up my lies,” he said, adding that he had asked multiple people to defend him. “What I did was horrible and then asking people to defend me was horrible.” His words were heavy but his tone stayed friendly. He was relaxed—in fact, much more so than I was. And his directness surprised me. He’d clearly thought through these answers, but they didn’t feel canned or rehearsed.

Steve volunteered that he thought his most extreme sin of this kind was going to Michael Kelly’s house to beg for his support. Kelly, who’d been the editor before Lane and later died reporting in Iraq, was bulldog-loyal to his young staff. He had once written a vicious letter to one of Steve’s sources who’d challenged Steve on the facts of a story, accusing the source of lying and demanding an apology. This letter got dredged up in the aftermath of the scandal and did not make Kelly look good. Did Steve not foresee that would happen? “I felt my entire life was falling apart around me, and I felt scared and desperate,” he said. “I wasn’t thinking about the ramifications of asking you to defend me.”

And so it went for several hours. I would ask Steve about something he’d done. He’d pause, conjure the moment, parse every iteration of the crime, add whatever I’d forgotten to mention, and then apologize. If the first step of reforming yourself is acknowledging your sins, then Steve was determined to get an A-plus, along with extra credit. For example, I asked whether he had consciously made us his co-conspirators in the creation of fiction. I recalled him once asking me to help with his story about the nonexistent Monica Lewinsky memorabilia convention. The story was dull but had a funny line at the end about a Monica Lewinsky sex doll. Were there any more details like that? I had asked, and he came to life, recounting various trinkets, including a condom named after her. I cheered him on, and thus together, we birthed a fabulous falsehood. Steve said he remembered doing that all the time, that “the normal editing process wound up directing the fabrications.” His most egregious creation, he said, was when he co-wrote a story with Chait about Alan Greenspan and invented an actual shrine to the then–Fed chairman. “I wanted you guys to feel something in my presence, to be excited to be around me,” he explained. “And as I crossed more lines, the lies became more and more extreme, and I just became more and more anxious and crazy and out of control.”

In his book, Steve’s fictional alter ego explained that he lied because he wanted to be “loved” by the people around him. At the time, that explanation struck me as generic, something a person relatively new to therapy might glibly repeat. But middle-aged Steve was now describing a very specific dynamic between himself and his audience, one that was humiliating to admit and felt more fully digested.

I asked him if he’d seen Shattered Glass. The movie came out around the same time as his book, and his editor had arranged for him to go to a screening set up by David Carr of The New York Times. Steve recalled that at first he couldn’t find the building. He was terrified that he would tell people he had the wrong address and they’d think he was lying. He said he couldn’t pay much attention to the film, and so he looked at his feet and cried. He thought it captured some of the drama really well, but that it got one essential thing wrong: “The movie makes it seem like there was some joy in all of this for me. But it never felt fun. I was anxious and scared and depressed. Outwardly I was communicating fun, but inside all I felt was anxiety.”

After a while, I stopped playing prosecutor and got a little more human. I told him, for example, that his book had made me furious, and he said he understood why.

“I was still self-justifying,” he said. “It was mean, in the sense that I didn’t imagine someone like you or Jon reading this and thinking, Hold on. I was the victim then.” He said he thought at the time that he had the emotional development to write a book, but it’s obvious to him now that he didn’t.

All of this might make you think that Steve was just telling me everything I wanted to hear. I did at some point ask if he ever allowed himself to fight back against accusations, even to get angry, and he admitted that he did not want to do that in public. But what put my suspicion on hold was the monumental shift in his tone.

In the old days, Steve used to walk around the office asking all of us, “Are you mad at me?” for no reason at all. Chait got so tired of it he vowed to whack Steve with a magazine every time he said it. Now, Steve would ask, every half hour or so. “Are you happy you’re doing this?” Or: “Is this how you expected it to go?” He hadn’t lost the need to solicit approval, only now the questions seemed less rankly needy, less narcissistic, and more the kind of friendly check-in any normal and nice adult might do.

In January, a few months before I interviewed Steve, the California Supreme Court declined to admit him to the bar. This decision ended his twelve-year quest to become a lawyer. In 2002, Steve had applied for admission to the New York bar, but withdrew his application two years later when he found out that it was going to reject him. He started the process over again in California in 2007, and both the state bar court and the hearing department ruled in his favor. But the committee of bar examiners kept appealing, and ultimately he lost by a unanimous decision at the state Supreme Court level. His case was highly unusual—even felons can become lawyers, after all. But the court ultimately decided that Steve had failed to prove that he “is no longer the same person who behaved so poorly in the past.”

A deciding factor for the judges was the discovery that Steve had misled the New York bar about how much he’d worked with various magazines to help detect his fabrications so they could inform their readers. He was still adding new articles to the list as late as the 2010 trial of the State Bar court. In his testimony, Chuck said he was astonished Steve hadn’t disclosed these articles twelve years ago. “If I wanted to get across anything new at the hearing,” he later told me, “it’s what a shock that was.”

The court also heard from 22 witnesses on Steve’s side—his girlfriend, a judge he’d clerked for, law professors he’d worked with, two psychiatrists he had seen, colleagues, friends, and Martin Peretz, who owned The New Republic while Steve was there and had reconciled with him. An emotional high point came when his girlfriend, Julie Hilden, was on the stand. She explained that she had gotten together with Steve shortly after the scandal, and he’d helped nurse her through a serious illness early in their relationship. The opposing lawyers asked why she hadn’t married him if she trusted him so much, and she started to cry. She told them that she and Steve had decided not to marry until same-sex marriage was legal in California. (I believe that she was sincere about this. I was friends with Julie many years ago, and she is a person who carries principles to an extreme—she wrote a book called The Bad Daughter about her decision to abandon her ailing mother so she could live her own life. Also, the veganism.)

The opposing decisions from the lower and state Supreme courts evince very different views of what rehabilitation looks like. To the Supreme Court, a reformed person is something like an oncologist; his eyes are trained on the offending cancer, his mission to root out every last trace. To the lower courts, a person reformed is no longer even engaged very much with the original crime. He has moved on, in a way that thwarts our hunger for retribution. If it isn’t already obvious, my sympathies lie with the lower courts. Whenever I read in the transcripts someone saying that Steve was “devastated” by his crime, as his former law professor said, always confessing, cataloguing, apologizing, I bristled. It sounded like the old Steve, always wondering if you were mad at him, consumed with some pre-existing shame. As a college friend once (brutally) said about him: “He could always absorb whatever abuse you threw at him. No matter what mean thing you said about his pants or his personality or whatever, he’d suck it up, like a beaten dog happy to get an open-fisted punch in the ear.”

To me, the most relatable testimony in Steve’s hearing came from Melanie Thernstrom, a journalist and an old friend of Julie’s and, ultimately, of the couple’s. Thernstrom found the court’s fixation on whether he’d listed all of his fabrications—“like was it 27 or 42?”—to be “sophistic.”

When Julie first told me she was dating Stephen, I was completely horrified, and as a journalist, you know, I had very strong negative feelings about what he did, as, you know, the members of my community all did, and certainly tried to talk her out of it.

Then getting to know him, you know, I went from horrified to skeptical, and then grudging, like, “Well he seems nice, but he probably isn’t, you know, deep down. I’m sure, you know, maybe it’s all an act, and then in getting to know him all these years, the dawning realization that this is really an extraordinary person, that he is really a wonderful person, an incredibly good partner, just very kind, generous, loyal, responsible, empathetic, someone who really cares about other people. ... This journey I took from horror to affirmation is one I saw every one of Julie’s friends go through over the years, and there is not one single friend of hers who doesn’t feel about him the way I do.

It is said that we are a nation of second acts, that at this cultural moment especially, we fetishize failure, that we love nothing more than a sinner reformed. But perhaps what we love is a story about second acts. A Christian testimonial or an Alcoholics Anonymous confessional is designed to be thrilling, but not too closely scrutinized. There is a long night of darkness and then, suddenly, a morning of light. But if we peer too much at the details, we get wary, or maybe bored. We might get some satisfaction hearing Eliot Spitzer say, “You go through that pain, you change,” but we don’t believe it enough to trust him to represent us. Perhaps what we lack is patience, because reform is not all that theatrical, or even a great story. It is slow, tedious work. You see a priest, or a psychiatrist. You acknowledge the sins. You go through a long period—years, decades even—of living with that acknowledgment, stewing in it, denying it, owning it again. If you work hard enough and are sincere in your efforts, then maybe each day you are a little more reformed than you were the day before. And maybe one day, the change can be detected on the outside.

One of the luckiest things that happened to Steve after the scandal was landing in the company of Paul Zuckerman, one of the partners at his firm. Steve applied to the job in 2003 in response to an ad. “What a genius,” Zuckerman thought when he looked at his résumé. “He clearly has applied to the wrong firm.” Georgetown grads who have clerked for judges normally don’t apply to personal-injury firms. But then Zuckerman read the cover letter, in which Steve wrote about his history. Zuckerman laughed, he told me, and promptly deleted the e-mail.

And here, the story gets a little apocryphal. Zuckerman thought about that letter for a while. When he was 35, he had a serious problem with drinking and drugs. He was married at the time and had a kid: “I was sick and I was in denial and I kept it all a secret. And finally it got so bad I had to accept that I could not control it on my own.” Most people will recognize this as the language of a twelve-step program, which is what it is. Zuckerman found himself in a “dingy room I thought I was too good for,” but eventually he settled in. He did his personal inventory, and “learned a lot about myself and my shortcomings.” Now he felt he might be in a position to help someone else do the same. He retrieved the e-mail and gave Steve a call. Of the 100 or so employers that Steve wrote to, Zuckerman was the only one to offer him a formal interview.

Zuckerman is precisely the kind of person you would expect to work in a personal-injury firm: He would look perfect in his Armani suit if he could only get ahead of his five o’clock shadow. When Steve came in for the interview, “he wanted to tell me the entire story in mortifying detail. I say ‘mortifying’ because at the time it hung so heavily on him. He was so sad, and it was so painful for him. I said, ‘You don’t need to tell me every detail,’ and he said, ‘I do. I need to know for myself that you know it all.’ ” Zuckerman then took Steve to meet one of the other partners and begged Steve not to go through the thing again: “It takes too long. We’re busy.” But Steve insisted.

Zuckerman hired Steve as a paralegal. At first he kept a close eye on him: “No way I was giving him my Social Security number and my mother’s maiden name.” Eventually, they found the perfect role for Steve—and here is where the tedious work of reform begins. When clients come in, Steve helps the firm get them ready for trial. The first thing he does is tell them who he is. He says he worked at a magazine and he lied and made up stories and covered them up. He says he got caught, that Hollywood made a movie about it and that there are many people “who dislike me and rightly so.” He has done this about a dozen times a month, for the last decade, meaning that the conference room in the firm’s modern, exposed-brick office has become his equivalent of Zuckerman’s dingy room, where Steve confesses, over and over again.

Zuckerman has Steve do this so the clients won’t find out about his history themselves and because he has to explain why Steve can never appear in court. But there is a deeper reason. In the firm’s lore, personal-injury work is like evangelism. “We are dealing with people who have not only been injured; they’ve been broken and need to be made whole,” says Zuckerman. In order to do that, the lawyers need to know the whole truth about a person, even secrets they’ve never confessed to anyone. But the clients are often afraid to disclose the truth because they fear it will hurt their case. So the lawyers have to work on them. “You can lie to your priest and lie to your wife,” Zuckerman says, “but you can’t lie to us.”

For example, Zuckerman explained, there was a client who got in a terrible motorcycle accident while driving home. The only witness who could verify his account of what happened was his mistress, who was on the motorcycle with him. There was another client who needed a doctor to testify about his health before an accident, but the physician who had seen him most recently had done an operation on his genitalia, which the client found embarrassing. When Steve opens with his confession, “it gives the client freedom to tell me what’s wrong with their life,” says Zuckerman. “They open up and tell you everything, even their secrets and things they are afraid to share. No one can do that better than Steve. He shares his background, and they know it’s safe for them.” Steve and the clients develop relationships. Sometimes he goes to their houses, makes them a meal. In the state bar court hearing, Zuckerman testified about Steve’s work with a “homeless crack-addicted mentally handicapped guy who lived in the streets under a tarp, HIV-positive” and who showed up at the office “filthy, fingernails 6-inches long, covered in fleas and lice and his own waste and his own filth.” Steve helped him to get into a homeless shelter, hook up with community services, and eventually, win the $2.1 million settlement in the garbage-truck case.

I heard this and alarm bells went off. The work sounded humane but also possibly manipulative. It sounded like crafting masterful stories in order to get the results you want. “Filthy fingernails,” “fleas and lice”—those all sounded like details out of an old Steve Glass piece. When I put this to Steve, he was a little touchy, although he’d already considered the ethics of his work. “It’s not manipulation; it’s caring. I don’t coach the clients; I help them discover their story.” He added: “It makes me anxious to do this. But I work from facts that are indisputably true. Maybe the anxiety comes from being afraid to be accused of lying again.” His answer didn’t satisfy me, but I figured he would work through this one in time. Winning a personal-injury suit requires facts but also a sympathetic narrative. Perhaps in a few years he’d be able to just admit that.

Change, after all, comes slowly. Zuckerman recalls that once, in the early days, he saw Steve crossing the street, and he was “the saddest guy in the world. He was just walking down Beverly Boulevard like that cartoon character with the stinky blanket and the cloud. He just looked like the world had taken a shit on him.” Then, in the last two years, the cloud started to clear. “He just began to like himself. I know this. I can sense it.” The final threshold, oddly, was the Supreme Court decision. Steve no longer had to defend what he had done or wait for someone else’s judgment. That’s why, when I sent him the e-mail, he so readily agreed to talk. “I felt so liberated, from that wanting to be loved all the time. It’s oppressive.” When the decision came down, he said, “I didn’t feel rejected, or desperate, or angry, overwhelmed. I felt sad and disappointed. I felt like my reaction was totally appropriate.” He took a day off work, hung out with Julie, and stopped waiting. It made me wonder if part of the reason the Supreme Court rejected him is because he was seeking their approval: the request itself was evidence that he didn’t yet deserve it.

During the bar trials, Steve’s childhood was depicted as a series of psychological traumas. Since the scandal, Steve has been in steady therapy, sometimes four days a week. One psychologist suggested that he may have “arrested development” and was unable to draw proper boundaries with his parents. The psychologist also said he suffered from a need for approval, a need to impress others, and a need for attention, and pointed to Steve’s fear of inadequacy and rejection. His father, who was a doctor, and his mother, who was a nurse, put “enormous pressure” on him to succeed at school, the court documents read. His parents would grill him and his brother on academic subjects, and the one who got the most wrong answers would be “frozen out” by his mother, while the other would be showered with love. When he was working at The New Republic, he came home for Passover one year and got his parents a subscription. They said the magazine was a “sandbox,” and it was time he grew up. He decided to create articles with “electricity,” and that’s when he began making things up. There’s no doubt that parental pressure played some part in what Steve did. But, as Jack Shafer wrote, the stories create a “cringeworthy picture of him. How many people would make the sort of confessions and excuses that Glass does in this case, just to gain admittance to the bar?”

In our interview, his views about his parents sounded more nuanced. Yes, they were pressure-cooker Jews, he admitted, “but I internalized the pressure much more than they put it on me.” He reads his descriptions of them in the legal papers and they sound “harsh” to him now. “I feel much more sympathetic, because I brought their world crashing down on them, too.” He said his parents had changed over time and so had he. Now, he thinks of them as “more like good friends who have a long shared history with me, but there’s no real feeling of dependence.” I pressed him on this, and he said that he was “wary to talk about them.” I had the strong impression that Steve had faced all these former versions of himself—not just the fabulist but the pleaser and the manipulator and the grasping Georgetown grad desperate to be a lawyer—and shaken hands with them and emerged from those encounters improbably content.

When Chuck Lane got the call asking whether he wanted to participate in Steve’s bar trial, he was somewhere between reluctant and game. He told the bar he would show up if they subpoenaed him. “I was trying to avoid seeming like I had a vendetta against Steve, which I don’t,” he told me. “I don’t want people to get the idea that, after all these years, I am out to get Steve. I don’t care if he’s in the bar or not.” Still, he told me, it was a free trip to L.A.

Chuck was not all that eager to meet to discuss Steve Glass, yet again, so I interviewed him over the phone. He is now a columnist at The Washington Post, and we talked while he was waiting to be edited. When Chuck arrived at The New Republic, we young people experienced him as a parent constantly telling us to clean our rooms. We were used to the delightful, conspiratorial antics of Michael Kelly, and Chuck was an actual grown-up. He had been a foreign correspondent for many years writing serious stories about Eastern Europe. He was not impressed with Steve or any of us bright young things. But we later realized that the character traits we least appreciated about Chuck—his sobersidedness, his suspicion of froth—were what ultimately made him the hero of the story. Steve was finally caught after a dramatic showdown, in which Chuck drove him to Bethesda to find the site of a supposed hackers’ convention that Steve had written about. Chuck pressed Steve for details—which building? what room? Steve kept lying and Chuck kept behaving like the reporter he was. We had to grudgingly admit it: he could not have handled it better.

Over the years, the scandal has made Chuck a “D-list celebrity,” he jokes. He was the hero of Shattered Glass, played by Peter Sarsgaard. He got admiring letters and e-mails from all over the world, and still does. “While the world would be a better place if it had never happened, it would be hypocritical to say it was some kind of heavy burden for me,” Chuck says. “It was a great feather in my cap.” At the same time, he added, “it tends to distract from everything else I’ve done in my career.”

What Chuck has always wanted from Steve, he told me, is a “full, voluntary, unrestrained, uninhibited, generous, forthcoming confession. And he never did that. How can you believe in a person’s change unless you know what the hell he did?” I told him about my trip to see Steve, and how he had seemed truly honest about everything he had done wrong. “If what you’re saying is true, if he’s really being truthful with you, then that’s the first evidence I’ve ever heard that maybe he’s finally got it,” Chuck said.

But he couldn’t sit with that impression for more than a few seconds. What Steve was telling me was a “classic one-source story,” because it all came from Steve, he pointed out. Then the train started up again: “It just goes back to the fundamental problem with all this. You can’t get your virginity back! You just can’t! Steve did something so spectacular and so dishonest on such a world scale that it’s going to stay with him forever, and not unfairly. People are entitled to doubt him now.”

Chuck does not generally seem like a hard-hearted or unforgiving person. But he went through something very different than the rest of us. We never confronted a panicking Steve and had him lie to our faces. When it comes to Steve, Chuck can’t get his virginity back, either. Chuck agreed with that theory. “This is a problem, and not a problem I can get over. I cannot believe what Steve Glass says. He went through the looking glass, and now I feel like Steve could say anything and I would be a fool to believe it,” he said. “That doesn’t mean I hate Steve, and it doesn’t mean I want Steve to fail in life or anything. I just don’t believe him. ... With me, he’s just forfeited the presumption that he’s telling the truth.”

The aftermath was different for Chuck, too. The Steve Glass affair became a central part of his public identity, perhaps even the moment when he was his most fully realized self. Whether he likes it or not, he will forever be defined by it, and whether he wants to or not, that’s hard to let go of.

After many hours of talking, Steve and I met Julie at a bar in Venice Beach. The place was packed; it was late, and I was jetlagged and a little cold. Our conversation had been so intense for so long that it slipped into a kind of normal. We talked about pets, Julie’s job, and a minor procedure she’d had. Julie told me they’d recently gotten engaged. They asked the waiter whether the food on the menu was actually vegan and admitted, in that cute couple way: “I know. We’re annoying.” Julie and I caught up a little on friends we had in common, and I had the thought that, if we lived in the same city, I might bump into Julie and Steve naturally, that I wouldn’t have to widen my social circle all that much for us all to land inside it.

I told Steve I was grateful he’d been willing to risk talking to me after all these years, and he said, “I missed you.” He told me that after college, Jon and I had been like his family, and that’s why he wanted so much for us to like him. My guard went up again. I was touched and simultaneously worried about getting taken in by him. Did he really miss me? Or was he saying he missed me as a way to win me over?

It was then that I realized that I was not the inspector come to peer inside him and discover whether the inner workings were free of rust. Forgiveness happens in a relationship. The transgressor has to make a palpable shift but so does the person who has been transgressed against. The day before I came to L.A., I had reread The Fabulist. This time, it didn’t move me one way or another. The parts that had enraged me before seemed minor, and I also noticed some moving moments of self-reflection I’d missed. That was my first clue that I, too, was no longer the same person I was in 1998, or 2003. Some people he has wronged will never forgive him. This doesn’t mean that the truth about Steve is elusive, or subjective. It means that forgiveness is a choice, and I decided to make it.

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Hayden Christensen’s last name.