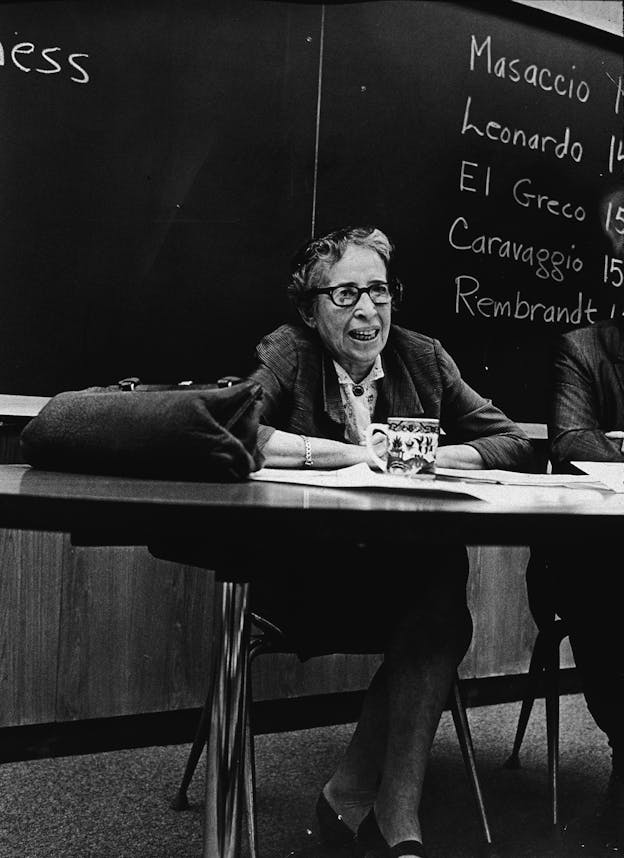

In 1959, a liberal journal of opinion published an essay on racial matters that created quite a stir. The editors of the magazine were outraged by the article, delayed it for a year and only agreed to publish it alongside lengthy rebuttals from its staff. In the following issues, the controversy spiraled. The editors, however, defended their decision forthrightly: “We publish it not because we agree with it,” they wrote of the piece, “but because we believe in freedom of expression even for views that seem to us to be entirely mistaken ... we feel it is a service to allow [this] opinion, and the rebuttals to it, now to be aired freely.” The magazine was Dissent. The author of the offending article was Hannah Arendt.

I’m glad someone published the exchange, because, all these years later, it makes for riveting reading. The article’s core contention is that the freedom to marry whoever one wants is one of the most fundamental political rights a liberal society offers. It is not a detour from civil rights, not a special right, not an attempt to revolutionize society, but the bedrock of civil equality. Without it, the equal protection of the law is a sham. Take it away, Hannah:

The right to marry whoever one wishes is an elementary human right compared to which “the right to attend an integrated school, the right to sit where one pleases on a bus, the right to go into any hotel or recreation area or place of amusement, regardless of one’s skin color or race” are minor indeed. Even political rights, like the right to vote, and nearly all other rights enumerated in the Constitution, are secondary to the inalienable human rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence; and to this category the right to home and marriage unquestionably belongs.

Arendt was as politically incorrect in her day as she would be in ours, of course, but her muscular liberalism contains a wisdom that still, I think, has resonance for both race and emotional orientation. Her point is that liberalism’s pursuit of equality should end in the public sphere. If it meddles in the “social sphere,” it destroys both itself and the freedoms it was designed to protect. And what she meant by the social sphere is even broader than what many conservatives defend today. Arendt argued that parents should not be forced to send their children to an integrated public school if they didn’t want to. She clearly would have opposed laws against workplace discrimination. And heaven knows what she would have made of affirmative action.

But, as a true liberal, she believed in the right to marry. It’s a strange paradox, this, and one worth reiterating. Marriage is a formal, public institution that only the government can grant; and yet it is also the most intimate and private of things, its meaning separate for each couple, its power a function of all those things—passion, jealousy, love, fidelity—that the cold, liberal state can never fully evoke. As such, it does what so few other things can: transform the private world by a public act. It is the intersection of the citizen and the person; the place where our public duties meet our deepest emotional needs.

So when this institution cut through the barrier of race, none of Arendt’s precious liberalism was compromised, but the world changed. It changed without infringing on anyone’s liberties, without spending anyone’s money and without setting up any government program. And yet it’s arguable that this simple act did more to proclaim our racial equality—and deepen our racial dialogue—than any other measure this century. Along with full voting rights and military integration, it was a cold, public act. But, unlike both of them, it also touched the human heart. It made the most important day in most people’s lives a celebration not simply of love and family, but of country and civil equality.

That is why it is so central to homosexual equality. Homosexuality, at its core, is about the emotional connection between two adult human beings. And what public institution is more central—more definitive—of that connection than marriage? The denial of marriage to gay people is therefore not a minor issue. It is the entire issue. It is the most profound statement our society can make that homosexual love is simply not as good as heterosexual love; that gay lives and commitments and hopes are simply worth less. It cuts gay people off not merely from civic respect, but from the rituals and history of their own families and friends. It erases them not merely as citizens, but as human beings.

This was Arendt’s point, too. Others were terrified of the consequences of such an idea. David Spitz argued in the same issue:

To fight now, as a matter of first principle, for the repeal of anti-miscegenation laws is, I believe, to give strength to the very contention that is most frequently, and by all accounts most tellingly, employed by those who resist the repeal of segregation laws—namely, the contention that this is but a device to promote sexual intercourse among the races.

Today, some gay leaders (and panicked Clintonites) similarly urge playing the issue down, for fear of backlash. But Arendt saw that they still didn’t get it. In an icy response to Sidney Hook’s argument that he preferred “equality of classroom” to “equality of bedroom,” Arendt wrote that “by calling abrogation of racial legislation ‘the equality of bedroom’ (I did not believe my eyes), [Mr. Hook] reveals very clearly how little he understands human dignity, however much he may be concerned with social opportunity.”

Her insight, of course, eventually became a commonplace, as the civil rights movement helped melt the interracial taboo. The process of integration—like today’s process of “coming out”—introduced the minority to the majority, and humanized them. Slowly, white people came to look at interracial couples and see love rather than sex, stability rather than breakdown. And black people came to see interracial couples not as a threat to their identity, but as a symbol of their humanity behind the falsifying carapace of race.

It could happen again. But it is not inevitable; and it won’t happen by itself. And, maybe sooner rather than later, the people who insist upon the centrality of gay marriage to every American’s equality will come to seem less marginal, or troublemaking, or “cultural,” or bent on ghettoizing themselves. They will seem merely like people who have been allowed to see the possibility of a larger human dignity and who cannot wait to achieve it. For better or worse. For richer or poorer.

In sickness and in health.