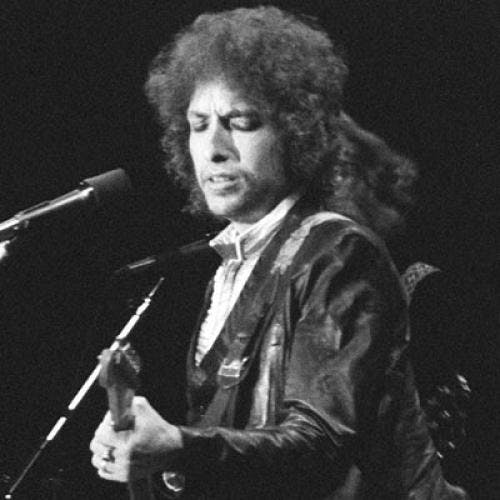

“Blood on the Tracks”

by Bob Dylan

(Columbia Records; $6.98)

Despite the blood he finds in his history and ours, despite the undistinguished music backing him, Dylan, his imagination and his voice are all in control again as they haven’t been so fully since “Blonde on Blonde” in 1966. And we can therefore expect “Blood on the Tracks” to flash the shape of the ‘70s as richly as his electric albums of the mid-‘60s voiced their own weird and wired days. If Dylan is right our current days are less wired and more acoustic, less grandiosely apocalyptic but more personally ominous, less anxious for surprise but more ambitious for nuance than our immediate past has been. Thus this new Dylan is less the mad man at the mainstream’s edge than the pied piper at the center of an established rock culture.

Hence his album’s wonderful reflectiveness, the way it calls on, judges and finds amply sustaining all the music that backed and amplified the stress of the last 20 years. Nearly every cut refers to earlier songs by Dylan himself or others. “Idiot Wind” recalls “Blowin’ in the Wind”; “You’re a Big Girl Now” re-approaches “Just Like a Woman” and “She Belongs to Me”; “If You See Her, Say Hello” evokes “Girl From the North Country”; “Buckets of Rain” reminds us of “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall”; and so on down the line. Still the titles are just beginning, for rock is now in that most interesting instant when an art turns from innocence to recouped sensibility.

Dylan has been trying to turn the corner ever since his misconceived “Self Portrait” (1970), in which his heavy affection fondled old favorites to death. Although “Blue Moon” and “Copper Kettle” couldn’t take it, the idea was to re-imagine the past for the present. The idea succeeds in “Blood on the Tracks” because he’s found a way to make songs like “Blue Moon” weave in and out of various cuts, leaving here a spoor, there a mood—resulting in a mature attitude that readjusts rock’s age of innocence, and that also refracts our own zealous innocence. Rock speaks to audiences who still remember the form’s earliest inklings in the span of their own lives. When a song today alludes to an earlier song, say “Blowin’ in the Wind,” it not only calls up scrapped phrases, riffs and licks, but also scrapped moments in our lives form the summer of ’63. Where were you when you first heard “How many seas must a white dove sail before she sleeps in the sand?” Remember Elvis’ “Hound Dog” in 1956? We’ve come a long way since then, as Dylan knows with some pride: “Well, I’ve struggled through barbwire…you know I’ve even outrun the hound dogs. / Honey, I know I’ve earned your love.”

Indeed he’s earned our love. He’s earned it by the constancy of his protean changes, which sanctioned our own flux. From protest posturing, through surreal symbolism, to country caricatures, his slippery style has always been hard to define. While his mercurial career has surely frustrated us, it has also been deeply attractive, for we too were trying on, and wearing ragged, America’s many costumes. If he has always come out on top, why, so can we: “I can change, I swear…I can make it through, / You can make it too.” And he’s earned our love by his involvement with common language, even in his most uncommon moods. He has saved phrases from our culture’s rhetorical slagheaps and centered them so singularly that they lease new life. He shoots juice to banality simply by kicking everything up several notches—best seen in the way these aren’t love songs, not love songs alone, but songs to his audience as lover. That’s no new trick for Dylan—he was performing it as early as “It’s All over Now, Baby Blue” (1965), and repeatedly the next year “Blond on Blonde.” But he hasn’t so consciously built an album around it before this one, which begins and ends talking to the audience as lover, which ends side on with “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go,” and nearly ends side two with the line, “I’m takin’ you with me, honeybaby, when I go.” These are the remarks of a lover, perhaps, but they are more likely the musings of a man engaging his audience at a turning point, and at a point that turns on the resources of common speech. For it was Dylan who, more than anyone else, saw how to go beyond copying the pop staples of blues, ballads and country in order to create a newly distinctive idiom.

Dylan’s role in the ‘60s was to expand the limits of popular song. He stood beyond the pale and called us to an outlaw reality. But now he’s returned to deepen rock’s cultural center. Quarreling with society in personal terms, he simultaneously sings of self and society in a way that profoundly enriches all our anguish about being separate from—yet within—our inevitable institutions. His new songs are about continued anger and acceptance, about continued hatred and love, and about the “the howling beast on the borderline that separates” his lover form himself, his audience form his voice, his country from his ideas [or vice versa], and audiences everywhere from performers everywhere. When he kisses that howling beast goodbye, as he says he finally has, the gain is not a solipsistic turn to himself and his lady alone. Rather he turns to a mature knotting with his audience and the sensibility he helped create: a stand-off embrace.

The last verse of the album’s last song describes how the performer finds his highest art by attending to himself in order to attend to others: “Life is sad, life is a bust. / All you can do is what you must. / You do what you must do and you do it well. / I do it for you, ah honeybaby, can’t you tell?” And that’s it right there: that immediate consistent and thorough involvement with an audience both characterizes rock as the primary popular form of our time and determines its promising esthetic. We can tell he’s doing what he sang nine years ago he’d do: “I’m pledging my time to you, hoping, you’ll come through, too.” We can tell: Dylan is back on the tracks.