One of my favorite novels of the century, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, portrays a totally discontented French scholar who gets a lift from the irrelevant material of daily existence only by listening to an old scratchy record of “Some of These Days, You’re Going to Miss Me, Honey”:

I think about a dean-shaven American with thick black eyebrows, suffocating with the heat, on the twenty-first floor of a New York skyscraper. The sky burns above New York, the blue of the sky is inflamed, enormous yellow flames come and lick the roofs; the Brooklyn children are going to put on bathing trunks and play under the water of a fire-hose. The dark room on the twenty-first floor cooks under a high pressure. The American with the black eyebrows sighs, gasps, and the sweat rolls down his cheeks. He is sitting, in shirt-sleeves, in front of his piano; he has a taste of smoke in his mouth and, vaguely, a ghost of a tune in his head. “Some of these days.” Tom will come in an hour with his hip flask; then both of them will lower themselves into leather armchairs and drink brimming glasses of whiskey and the fire of the sky will come and inflame their throats, they will feel the weight of an immense torrid slumber. . .

That’s the way it happened. That way or another way, it makes little difference. That is how it was born. It is the worn-out body of this Jew with black eyebrows which it chose to create.

Little as this may apply to the forgotten Shelton Brooks, who wrote “Some of These Days” back in 1910, it does recall, like some old Warner Brothers film biography, the remarkable feats, with or without whiskey, sometimes without a piano, of Israel Baline (Irving Berlin), Jacob Gershvin (George Gershwin), Hyman Altruck (Harold Arlen), and a whole army of arduous immigrant derived tunesmiths and song pluggers whose romance with America, and with romance itself, established the success of Tin Pan Alley.

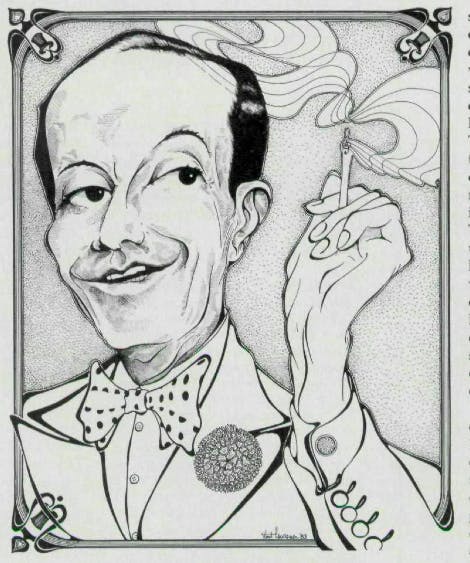

Cole Porter from Peru, Indiana, (Yale ’13, Keys and Skull And Bones) was distinctly different, and not only because he was (almost always) “cool” and “high society”; he was his own lyricist, and the wittiest and most resourceful master of the double entendre in the generally uninspired body of American vers de societe. Only in our musical theater has Broadway consistently justified itself. Only because he was so fashionable in international society as to be, up to the very late 1920s, unfashionable for Broadway, was Porter able to get his enduring wit and mischief into musical comedy. The Complete Lyrics of Cole Porter is the fullest, heaviest, and most sumptuous proof of just how delightfully Porter has endured.

Others might accentuate the positive. Porter slipped easily into the negative. He was not a romantic (except about Yale friendships) and his passion for women, a very general one, was less marked than his delight in “friendship”:

If you’re ever down a well, ring my bell.

If you ever catch on fire, send a wire.

If you ever lose your teeth and you’re out

to dine,

Borrow mine.It’s friendship, friendship.

Just a perfect blendship.

When other friendships are up the crick.

Ours will still be slick.

He was married for some thirty-five years to a very wealthy woman, older than himself, who was once “the most beautiful woman in the world,” but whose first marriage “turned her off the sexual side of marriage.” This was definitely a relationship without amatory sweat. Still, Porter, already rich, was launched by marriage into life with the “rich rich.” The Porters were chummy with the Prince of Wales, Lady de Mendl, Bernard Berenson, Noel Coward, and of course Elsa Maxwell, a now forgotten prop of “society” who at one time was as indispensable as a Pekinese. Porter smoothly denied that he was a snob—“I just like the best.”

The legends about the whole European idyll of Linda and myself are greatly exaggerated. It is true that we bought a $250,000 house in Paris with zebra rugs and a platinum-leaf room, but we rarely used it. We were generally somewhere else—England, Italy, or Spain. As for the four-year lease on the Palazzo Rezzonico [Venice], it is true we held parties which the social set of that day felt to be a little dazzling.

But, as Porter said when Warner Brothers produced an absurd film about him, Night and Day, in order to cash in on the fame of that song, “If there is one thing my songs have never fitted, it is my life,” Difficult as it is to believe now, the “love that dare not speak its name” was once as private as royalty’s. Porter knew how to intimate sexual mischief without offending; his greatest gift as a satirist, the mainstay of his verse, was his ability to share a secret with his audience. This he did by lampooning sex as physical drudgery. In DuBarry Was a Lady (1939), he had Ethel Merman sing to Bert Lahr:

When the light of the day

Comes and drags me from the hay.

That’s the time

When I’m in low.He replies: Have you tried Pike’s Peak,

my dear?

Kindly tell me, if so.She: Yes, I’ve tried Pike’s Peak, my dear.

But in the morning, no, no-no, no,

No, no, no, no, no!

In “Nobody’s Chasing Me” (Out of This World, 1950):

Each night I get the mirror

From off the shelf.

Each night I’m getting queerer,

Chasing myself.

Ravel is chasing Debussy,

The aphis chases the pea,

The gander’s chasing the goosey,

nobody’s goosing me.

Porter’s famous but untypical torch song, “Night and Day,” was inspired, he said, by a Mohammedan call to worship that be heard in Morocco. He liked to start with a rhythmic beat for which he then found the words, and finally the music. Of course it is the aggressive repetition in “Night and Day”—“Like the beat beat beat of the tom-tom/ When the jungle shadows fall”—and the typical internal rhymes following the quintessential Porter spoofing of the body “under the hide of me/ There’s an, oh, such a hungry yearning burning inside of me” that make us sit up. The lonely, genuinely visceral plaint in a great love song like Arlen’s “Stormy Weather” moves us. The sad weather is in the soul, and is a driving metaphor. But the “flair” of “Night and Day” comes not from the feel of “burning” but from Porter’s typically detached use of a simile—”like the beat beat beat of the tom-tom.” He used lyrics as word games and never moved without thesaurus and rhyming dictionary.

Porter’s upper-crust spoofing, not least of his own set and its endless social busyness, was one way of suggesting the sexual entanglements and complications that were his favorite material. These he had to get down the hungry money maw of a musical theater that needs to be a total smash in order to survive at all. This drive also keyed him up to astonishing feats of last-minute cleverness. He was in fact frequently censored. This wonderfully complete and annotated collection lists song after song that had to be dropped, and not just because they didn’t “work.”

Yet his increasing success, especially in the 1930s, obviously depended on a very specialized social experience. Porter obtained his creative energy from seemingly endless camaraderie. At first he and his wife entertained so lavishly in the hopes of obtaining an entree to Broadway. The composer behind many famous Yale shows and the ironic composer of such professionally virile Yale hymns as “Bingo Eli Yale” and “Bull Dog,” Porter not only seemed to live in the midst of a party, but often got his best ideas from one. He sometimes depended on other people to fill in a lyric, and he liked to tell the story (in two different versions) of how his friend Monty Wooley had furnished the great line “It’s de-Lovely” (from Red, Hot and Blue! 1936) after Moss Hart had said of Java that “It’s delightful,” and Porter chimed in “It’s delicious.”

How much Porter’s most famous songs—”Anything Goes” (1934), “I Get a Kick Out Of You” (1934), “You’re the Top” (1934), “Just One of Those Things” (1935), “Begin the Beguine” (1935), “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” (1936), “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” (1938)—owed to his friends, his frank need to win their love by constantly entertaining them! The line between making a hit and being loved for it is more indistinct in show business than elsewhere. From childhood on, and of course at Yale, Porter always used his music to ingratiate himself with every one. Photograph after photograph shows him at the piano, everyone around him (even Louis B. Mayer) wreathed in smiles.

Porter (born 1891) was in every aspect of personal style and some necessary impudence a product of the 1920s who became a Broadway favorite in the 1930s. What this says about the Depression era is interesting. The crowd in black tie at a Music Box opening never suffered as the “truly needy” did. Yet even in this crowd, as Ernst Lubitsch, Cary Grant, Irene Dunne made clear in still-amusing movies, there was a general cry for entertainment approaching the risque. Lighthearted wit often took the form of self-parody.

Porter was a champ at this. In the ’20s, that natural time for “golden youth,” he learned the essential air of confidence, even of personal sovereignty, that made that decade a perpetual modernist show, and this made the ’30s all the more grateful for his impudence. His critics make this clear. Because of the great success of Kiss Me, Kate in 1949, Edmund Wilson was eventually to accuse Porter of selling out. In Hemingway’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro, a dying writer in Africa (supposedly modeled on Scott Fitzgerald) drinks a last whiskey and soda and bitterly mimics Porter’s “It’s Bad For Me.” Porter had obviously gotten under the skin of people who forever identified themselves with the ’20s.

But what the Depression crowd in black tie at an opening gained from Porter was the assurance that America, their America, was still standing. The “best” people still deserved the best. Porter’s “patter,” as he liked to call it, was the ultimate goods for people with dough. He and his wife had been “everywhere”; he spoke French, Italian, German, Spanish; he knew Greek so well that in Jubilee (1935) the “Sapphic ode number” was spoken in Greek as June Knight danced it. Setting out to master Russian, he said “that which I do learn will be enjoyable when I take that big country place in Crimea.”

Anything Goes (1934), my favorite Porter show, had the perfect title for a Depression audience. “You’re the Top” became the most famously clever Porter lines. Of course the song would not have been the same without Ethel Merman, who was still Ethel Zimmerman when Porter found her, and who was to become as necessary to a Porter show as the words to his music. Merman (Arturo Toscanini said that she was not a voice but a powerful musical instrument) had a genius for belting out a line as loudly, smashingly, and above all as clearly as possible. When Porter could not catch just one word at a rehearsal, he called her at three in the morning to reprimand her; she never made that mistake again. “You’re the Top” made a serenade to the “best,” to the most recherché and the most expensive, to the things that only money could buy and that only money had seen.

You’re the top

You’re the Louvre museum

You’re a melody from a symphony by Strauss

You’re a Bendel bonnet

A Shakespeare sonnet,

You’re Mickey Mouse.You’re the Nile,

You’re the Tow’r of Pisa,

You’re the smile

On the Mona Lisa.

What these words said in dark 1934 was that America was safe because its products were as good as Europe’s.

The serenade was not just to “things,” however, but to the audience rejoicing in instant gratification, which Porter, too, provided. Such sharing and connection with an audience in the musical theater are not common in the American theater. They are not usual even in American “light” poetry. Of course all clever lyricists, punsters, satirists, and parodists make people laugh for a moment. But compare Porter with such gifted providers of words to other people’s music as Lorenz Hart and Ira Gershwin, and you see the advantage Porter drew. His words were entirely words to his own music, and the wit of his words depended on his ability to raise the audience immediately to his own level—and to keep it there. The instant happiness that Porter gave his audience is the kind that becomes history.