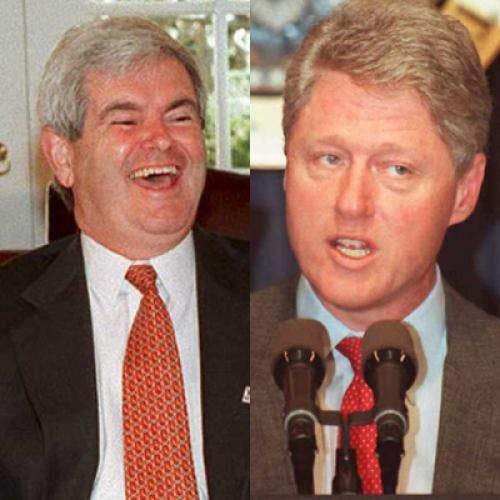

Those with sympathies for Bill Clinton might be tempted—perhaps rightly—to view last Tuesday's election returns as an unmitigated disaster. Never mind sympathies; condolences seem in order. Newt Gingrich as speaker? Pete Wilson re-elected handsomely; moderate Democrats like Dave McCurdy and Jim Cooper humiliated; icons like Ann Richards and Mario Cuomo smashed. Worse still, Senator Alfonse D'Amato now controls the Banking Committee and the governor of New York. Let the Whitewater hearings begin! Jesse Helms could make life impossible at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee; and the occasional brilliance of Daniel Patrick Moynihan will no longer guide the Senate Finance Committee. Within the Republican Party, as Fred Barnes pointed out in these pages ("The Newtoids Cometh!" November 7), the shift toward Gingrichism is made more acute by the new speaker's triumph in the House. We may soon look back on Bob Dole's period of ascendancy as a responsible era. Even when Democrats won, it was hard to hope: when the big winners in the party are Chuck Robb and Edward Kennedy, it is not exactly a moment of renaissance.

And yet—the voters were moody, but they did not go nuts. Michael Huffington, the worst little hologram in Texas, did not win in California, after spending $25 million (our only regret is that he did not spend $50 million); Oliver North, with a huge turnout from the radical right and an enormous amount of money, lost easily in Virginia; the empty suits of Mitt Romney and Chuck Haytaian will not go to the Senate; even in the District of Columbia, Marion Barry was delivered a rebuff—if, alas, not a defeat—from a feisty Republican, Carol Schwartz. The ejection of the jurassic Dan Rostenkowski, the exhausted Tom Foley and the drab Jim Sasser showed a healthy popular disdain for Washington types who take their electorates for granted. And just why should New Yorkers have re-elected Mario Cuomo for yet another term of paleoliberal drift? In this admirable desire to shake up the system, Americans have now joined the Japanese and the Italians in unseating an ancient and moribund political satrapy—in this case, forty years of increasingly complacent and corrupt Democratic hegemony.

Moreover, it would be wrong, we think, to see this election as simply a rejection of Clintonism. In some ways, Clintonism, as originally conceived, is consistent with what the voters have just expressed. In 1992 it was clear that a moderate Republican, George Bush, couldn't deliver domestic reform with a divided Republican Party and Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. So when Bill Clinton and Al Gore ran as moderate Democrats, geared to new, practical solutions to social problems, they were given a Democratic Congress to help them. They promised to cut middle-class taxes, reinvent government, trim the deficit, reform both welfare and health care. But it turned out in office that the institutional pull of the Old Democrats was too strong. Welfare reform was put off; health care reform, thanks to that crusty paleoliberal, Hillary Rodham Clinton, became a massive Great Society contraption; a stimulus package was attempted and then aborted; even laudable reforms—such as ending discrimination against gays in the military—were presented as concessions to liberal interests. Because of this, the good things Clinton and Gore did—cutting the deficit, expanding free trade, helping the working poor, supporting a democratic Russia, rescuing Haiti, even reinventing government—were obscured in the public mind. And Republicans played a cynical game of opposition.

The good election day news for Clinton is that Republican game is now over. Republican power without responsibility disappeared this week. Voters responded to Clinton's entrapment in Old Democrat politics by giving him a powerful weapon: a Republican Congress. The president should now call the Republicans' bluff and give them what they want. Don't play a Truman game: you're too weak. Do the opposite. Propose a tax cut, but insist on a line-item veto to cut spending to match it; demand that Republicans propose a budget that actually will end the deficit—and promise to sign it; push for a tough version of welfare reform that Republicans won't dare oppose; insist that the Republicans pass GATT, or accuse them of obstructionism; move reinventing government again to the top of the agenda and dare Republicans to run away from it; propose a moderate health care reform package and insist that Congress play ball. What, after all, at this point, has the president got to lose? He might even rediscover what got him to the White House in the first place.