CLOSE THAT COPY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS. IT’S O.K.

Clip the coupon below to let Foreign Policy guide you through the next critical year.

— Advertisement in Foreign Affairs, Fall 1993

I think I can pinpoint the moment I first felt obliged to be interested in foreign affairs. It was during a steamy New Orleans summer between high school and college, when, after a local worthy ridiculed me for never having heard of Rebecca West, I found myself bench-pressing a copy of Black Lamb and Gray Falcon, the author’s 1,200-page study of Yugoslavia. The map at the front immediately confirmed my suspicion that Yugoslavia lay somewhere between England and China. I read on, with a growing self-esteem, until I arrived at page 2. There I encountered the marvelous passage that has haunted me ever since, in which the author describes herself lying in a London hospital bed in June 1914, and hearing the news on the radio that the Archduke Ferdinand had been shot in Sarajevo by a Bosnian terrorist:

I rang for my nurse, and when she came I cried to her, “Switch on the telephone! I must speak to my husband at once. A most terrible thing has happened. The King of Yugoslavia has been assassinated.” “Oh dear!” she replied. “Did you know him?” “No,” I said. “Then why,” she asked, “do you think it’s so terrible?”

Her question made me remember that the word “idiot” comes from a Greek root meaning private person. Idiocy is the female defect: intent on their private lives, women follow their fate through a darkness deep as that cast by malformed cells in the brain.

I doubted many others who read this passage identified with the nurse. The prejudice against the provincial outlook rarely has been so lethally put, and it proved too much for ordinary adolescent defenses. Out went seventeen happy years lived in ignorance of Yugoslavia, archdukes and other places and characters remote to my experience. In came a strained interest in global affairs, inspired by a terror of a life of idiocy. News from abroad became the homework of real life. The West Bank ceased to be the other side of the Mississippi River Bridge; the Jordan river was no longer the place just across the state line where people went to fish and water ski. It was not a pretty sight, this intellectual awakening. It was hardly a substitute for a passionate curiosity about, say, the politics of sub-Saharan Africa. But there it was.

I mention this experience in part because I imagine that a lot of people reared in obscurity trace their interest in foreign affairs to a fear of being thought idiots by sophisticates. But it also provides a counterpoint to a more recent encounter with another book published the same year—1941—as Black Lamb and Gray Falcon, the memoir of William Alexander Percy, called Lanterns on the Levee. Percy also recalls June 1914, which he spent climbing Mount Etna with a pair of drunken Sicilians:

He [one of the sozzled Sicilians] said they were scared this time because ours was the first ascent anybody had made since the last eruption. He added that the last person he had guided to the top was an Austrian grand duke. I was not interested in Austrian grand dukes and wished he would shut up. He continued that in yesterday’s paper he noticed the grand duke had just been assassinated at Sarajevo; one duke more or less — what time did we start up the crater for the sunrise?

Of course this is partly an author’s joke on himself, but only partly. The rest of the memoir is much of the same: a tale of an important life lived rooted wherever the author happened to be, usually Greenville, Mississippi. Percy was a planter, poet and lawyer, the son of a U.S. senator, the uncle and up-bringer of the novelist Walker Percy (who said of him that “he was the most extraordinary man I have ever known”) and a hero in the war that followed the archduke’s murder. And yet his attitude toward world history, at least in his memoir, remains rather passive. He knows it is important but he cannot do much about it and so he will simply take it as it comes.

This willful anti-worldliness is poles apart from the fashionable omniscience of the intellectual, and was no doubt something of a pose. But that’s almost the point. It is nearly impossible today to imagine even the average big-businessman, much less an artist and thinker of Percy’s stature, striking a similar pose. The global perspective is in: when an archduke bites the dust, if you are a certain kind of important person, you want to be the first to grasp the global ramifications. When Sir James Goldsmith, the corporate raider, retires to write a book, its subject is a foregone conclusion. A recent full-page ad in The New York Times explains that the author “brings his challenging perspective” to, among other global issues, “the true effects of global free trade and GATT”; “why the new world order proposed by the West is deeply flawed”; and “why, despite our extraordinary economic success, we have destabilized our society to a deeply dangerous extent.” (He should know.)

You can always see current fashion best in whatever it is that young ambitious people are aping. Coming out of college in the early 1980s, I remember, you would ask some lucky person who had gotten admitted to the Harvard Business School or the Harvard Law School what he or she intended to do afterward, and invariably he or she would reply, “international finance,” or “international law.” I’m now almost sure that no college student really knew what was meant by international finance, and there wasn’t any international law that mattered. (I don’t think these people had the sea lanes in mind.)

What appealed was the notion of “international.” This collegiate internationalism was not the romantic, Byronic lust for foreign adventure—though there was some of that in the air, too—but the anti-romantic quest for importance. To be suspended between nations sounded portentous. The trick was to remain forever uprooted; to go home was an admission of failure. (Nevertheless, home clearly remained the reference point; people left it to see distant things, no doubt, but also to be seen from a distance.)

It turned out that the attitudes of those of us in college mirrored fairly well the attitudes of our most ambitious elders. About the only high status role left in an American commercial bank, for instance, was overseas, lending money to Third World countries that could never repay. The most sought-after jobs at national newspapers were in foreign bureaus. This is still true. The farther away the news, the more prestigious it is to gather. Imagine! Some of the most talented reporters at The Washington Post, positioned at home to observe and influence the world’s most powerful nation, want more than anything to be sent to Tokyo or Moscow, where they will be at once, strangely, more marginal and more important.

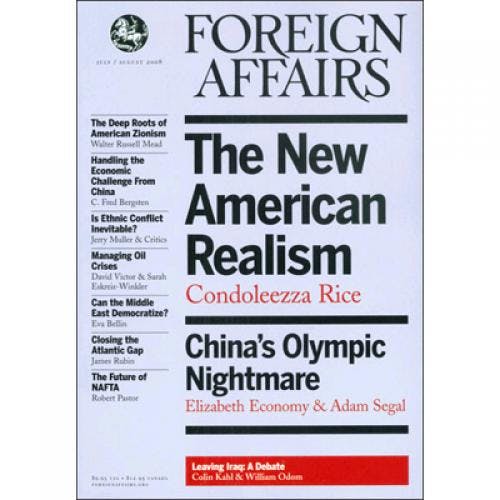

At the very top of the food chain one sees a lot more of the same. Call it the prestige of distance. However irrelevant the modern ambassador, for example, very important people still fall over each other to become one, and thus consign themselves to a future of stilted dinner parties and lost passports. And at a time when anyone with eyes can see world-class problems inside America, the favored meeting place of serious American problem-solvers is still something called the Council on Foreign Relations. Not “of” but “on.” What does it say that the quickest way for the man of affairs to establish that he is a Thinker is to publish an article in the council’s magazine, Foreign Affairs? It says that people whose minds are occupied by things far away are considered more profound than people whose minds are occupied by things close at hand. One subject alone, albeit broadly defined, is deemed worthy of the professional important person. The world!

But it is an odd world, forever on the brink of some crisis, upheaval, beginning or ending, all full of bangs with nary a whimper. Open to almost any article in one of a dozen prestigious American journals of foreign affairs and you find something like this:

The answers to two great questions will soon set the direction of the world economy. One: Will the industrialized democracies cooperate to sustain an open, market-oriented world trade and financial order? To do so, they must rise above the different ways they practice capitalism and mounting domestic pressures for economic nationalism. Two: Can these countries integrate into such an order those countries that are turning from state controls toward market capitalism?

— Robert D. Hormats, “Making Regionalism Safe,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 1994

Can any sane person really believe that the direction of the world economy—or any other global phenomenon—will be set soon, and by the answers to two great questions? As it happens, the same issue of Foreign Affairs ran an article by the economist Paul Krugman that pretty well undermined the urgency of this one. Krugman argues persuasively that the current rage for the world economy is a bit of a canard. The effect of world trade on the U.S. economy, for instance, is so small that it almost can be ignored. Our standard of living hinges chiefly on our domestic productivity. What matters is how efficiently we make things for our own consumption, which in turn depends on our willingness to save and invest locally.

Not that it matters very much. One of the characteristics of the above passage, which it shares with nearly all writing about global affairs, is that it will be read with the same grave attention no matter what it says, as long as it says it seriously. (Which is why there are no amusing articles about foreign policy.) The status of the subject does the rest. It is a very definite kind of writing, this global bigthink, distinct from any other except maybe the conservative religious tract.

The first thing you notice after a few hours of flipping through the relevant journals, for example, is a perverse taste for the big blind leap into the future. The incentive system of the global theorist encourages what politely is called vision and more normally is called guessing. To wit: “China is poised to become an economic power in the twenty-first century if centrifugal forces do not pull it apart” (James D. Robinson iii, “Moving the Fed into a Global Age,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 1994); “Of great service in its first fifty years, the World Bank group will render even greater benefits in its next fifty years if, unlike most institutions, it can adjust to the vast changes that have occurred since its founding” (Henry Owen, “The World Bank: Is 50 Years Enough?” Foreign Affairs, September/October 1994); “It is possible to imagine a future of Russian capitalism that asserts itself early in the twenty-first century as the envy of the world” (Jude Wanniski, “The Future of Russian Capitalism,” Foreign Affairs, Spring 1992); “The end of the cold war means that the German question, far from being solved, has just begun” (Lanxin Xiang, “Is Germany in the West or in Central Europe?” Orbis, Summer 1992); “Given its regional and international influence ... there is reason to hope that Turkey will be able to overcome its difficulties and assume the leadership role for which it seemed destined” (Eric Rouleau, “The Challenges to Turkey,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 1993); “In general, the Jugoslav question may be said to be one of time” (Hamilton Fish Armstrong, Foreign Affairs ... June 15, 1923).

If there is nothing under the sun that hasn’t been predicted by someone in Foreign Affairs it is because the price of guessing wrong is low and the rewards for guessing right are high. The global thinkers of the recent past who have enjoyed the greatest acclaim are not those who have been right but those who have been melodramatic. Being wrong by itself does not ensure success, of course. George Kennan was mainly right about the Soviet Union, for example. But everyone now knows that if you are able to make an outlandish prophecy about the globe, or some large part of it, plausible for just a little while, you will forever be treated with respect, as was Malthus. (See the spectacularly wrong arguments of Jean-Francois Revel’s How Democracies Perish, Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth and Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History.)

Thus the other common trait of this sort of writing: the banality of its language. At first glance you wouldn’t expect it. If you had a Big Worldview to air you’d think you would want to serve it to the reader as a giant neon pink soufflé—for all the world to see. But reading the various global prophecies and analyses in prestigious journals is more like eating the hole of a doughnut. (How many articles in The New Republic on foreign policy do you remember? Me, none except an unintentionally funny one about rebuilding Israel on a reclaimed island in the Mediterranean.) The telling detail goes unreported because no detail is observed. No detail is observed because the writer is not interested in what is right under his nose, assuming he actually ever gets his nose abroad. The imagined world here is literally senseless—no one in it ever tastes, touches, smells, hears or sees. The writer with the big worldview free-floats, like a man in a sensory deprivation tank. Or a dream.

I think the reason for this detachment—in addition to a lack of curiosity about actual foreigners—is that the moment you introduce any sort of concrete detail into the typical piece of globe theory, and thus make it vivid and real, the whole imagined world melts, like a wicked witch under water. The globe-thinker’s world is not the world around him. It is the world he sees down there from up here. His flight from one kind of idiocy takes him nearly full circle into another, into the small group of people who allow themselves to think of the world from above. The delusion of omniscience follows naturally.

The practical consequence of this weird but widely acclaimed global outlook is to channel smart and influential people away from problems they might solve and into problems they cannot. From reading the American newspapers, I know more about race relations in South Africa than I do about race relations in America. The idea of alleviating poverty in our own country has died; meanwhile, through the World Bank, Americans devote billions to alleviating poverty abroad. About the worst way for an American president to boost his poll numbers is to try to govern at home; the best is to travel abroad and have his picture taken with foreigners or, even better, to wage war against them. And so on. Stop thinking of the subject as foreign affairs and start thinking of it as the tendency to focus on events that take place at great emotional and physical distance at the expense of more immediate events, and suddenly our various prestigious global obsessions look more like the tabloid obsession with the O.J. Simpson murder trial. (Like celebrities, foreign countries are handy vehicles for fleeing private life into some publicly staged simulacrum.)

The general belief that what is far away is more important than what is close at hand necessarily corrupts private life. What does it matter if you spend one-half of your day bungling a financial conglomerate if you spend the other half worrying about the world financial order? I recently met a woman who recalls growing up with a mother who was always busy with one foreign cause or another. When she was 5 her mother put her on the bus downtown with a credit card and a note for the salesman at the department store, instructing him to outfit her for the coming school year. It’s a small but familiar example of the sort of private moral transaction that can be done by the person who learns to live life globally. I’ll bet the deal this woman cut with herself—without articulating it, of course—was something like this: sufficient compassion about the latest Great Global Outrage lets you off the hook in your daily life. There are trade-offs to be made in the private budget of our concerns. What is traded off in a certain kind of worldliness is the sanctity of ordinary existence, the ritual of daily life.

Of course this is nearly the opposite of the current most righteous moral sentiment. A few months ago The New York Times published an interview with Susan Sontag in Sarajevo. She compared her decision to be there to George Orwell’s fighting in the Spanish Civil War, and declared it was the moral duty of every intellectual to join the Bosnian struggle. Here was Rebecca West one-upped: the junior college professor who remained safely at home nestling to his bosom family and students was not merely an idiot. He was immoral! And I confess that for the tiniest craven moment I almost caved. It was a powerful combination, Orwell’s moral authority coupled with my occasional desire to escape the life around me--that tingle of dissatisfaction with the here and now.

But I’m not so sure where Orwell would have put himself were he alive and well in America today. He went to Spain to fight Fascists at a time when fascism threatened his way of life in England. That is, his concern with Abroad grew out of his immediate interests at Home rather than an abstract commitment to fighting evil everywhere on the globe. Orwell’s moral authority, like his literary genius, sprung from his ability to see the universal in his own experience. From the black shirts under his nose he rightly understood that he was living in the midst of an international ideological struggle. We are not. From what is under our nose we can see that we are living in a world of neighborhood wars. Who knows? If Orwell had started here and now in America perhaps he would have gone off to fight in Bosnia. But I’d like to think that instead he would have found the road to East L.A.

Michael Lewis is a former senior editor of the New Republic. His latest book is The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine (W.W. Nortion & Company).